I began the blog project A Year of Positive Thinking with no end date in mind and it has proved to be an elastic and metaphoric time frame. It celebrates its fourth anniversary today. Today’s post is an updated table of contents featuring about seventy posts in an easy to search format that I hope will help give a sense of what I have done on this site in the past four years.

My first post on A Year of Positive Thinking was published April 28, 2010. In “Looking for art to love in all the right places” I teased out the different ways one can fall in love with an art work, as opposed to a person. My first project was to go out into the city I live in, New York, in search of art that I love, in keeping with the goal of the blog, which was to turn my attention to the art work that sustains and inspires me, in contrast to the works with which I have engaged in equally vital though perhaps more “negative” polemical battles in many of my other writings, including my 2009 book A Decade of Negative Thinking, whose title suggested this blog’s antonymically eponymous title.

As a friend said, well, that lasted about two weeks. Indeed, it has not always been easy to stick to the positive. Nevertheless in a world that rewards positivism, where things must be “amazing!,” a critical but passionately skeptical voice may have “positive” utility to cultural discourse. As I point out in the “About” page of this blog:

A Year of Positive Thinking may turn out to be a battleground between the two sides of my personality, something like Cassandra and Pollyanna! Cassandra tells truths no one wants to hear and Pollyanna actually does the same thing: she’s not the sweet cloying character we think of when we use the name in a disparaging way, she looks right at what she sees in the dysfunctional little town she has come to live in and her engagement with the people she meets sets in motion positive change.

I published fifty-one posts in the first two years and have published thirty-nine since. The slight decrease in the number of posts is relatively minor but to me it’s indicative of a number of factors which reflect different but familiar aspects of contemporary life. The writing I do here exists on the border between the aimless time of flânerie and the ticking clock of the 24/7 news cycle. I love to wander around, look at things, read things, trawl the web, an often solitary and anonymous paladin of the cultural field, and put things together that perhaps no one else would, without the concerns of daily journalistic deadlines or the schedules of the art market but I also want there to be a sense of necessity and I enjoy the moment when I realize that outside events provide an impetus and impose a schedule where “I have to” pull a text together in a very short time frame. Both these aspects of time require a certain independence of mind that benefits from a relative degree of financial independence or at least marginal security. I began the blog in 2010 with the help of a grant from a Creative Capital Warhol Foundation/Arts Writers Grant and in one of those moments of irrational but precious optimism that artists are able to pin onto the most minute signs of career movement. Over the past four years, for me as for millions of others, conditions have tightened while work loads have multiplied. So going to see exhibitions becomes like “playing hooky,” and writing for A Year of Positive Thinking seems like a guilty pleasure, time stolen away from other duties.

Another factor in my writing a bit less often on A Year of Positive Thinking in the past two years is that I have found it expedient to put onto Facebook content where I feel I can write a few words quickly around a link or image. There is something alarming or just plain stupid about entrusting cultural discourse to a site where there is always the possibility that it could all vanish just like that, by corporate fiat, and where, at best, material quickly becomes functionally unavailable as it drops down the page into social networking purgatory. Nevertheless, the extemporaneity and informality of such communication sometimes generates quite interesting comments threads where I may end up writing about as many words as I might have for a blog post, but with less pressure to build a coherent argument. I have never used this blog, as many other art bloggers do, as a regularly published site for the aggregation of art-related news stories by other people, I’ve used Facebook to perform that function and reserved A Year of Positive Thinking for long form, speculative non-commercial art writings. I have published a couple of the resulting Facebook discussions on A Year of Positive Thinking, with permission of the participants. Both the blog and my interventions on Facebook involve an approach to writing that is very different than the way I wrote long essays for M/E/A/N/I/N/G and for my books: I enjoy the challenge of capturing the speed and intensity of conversation in something like real time while trying to maintain some kind of standard of clarity for expository text. There is a high wire/seat of the pants aspect to the writing of a blog post: how will I pull together a constellation of thoughts, opinions, recollections, and references in a limited framework of time and length?

Publishing on a blog allows for instant communication and at the same time the blog posts remain available on the web as long as the yearly upkeep is paid. They can be accessed at any time via the tags and the timeline to the right of the page. Yet online publishing also fosters instant oblivion, in a way that a book does not. I hope this four-year table of contents featuring about seventy posts will help give a sense of what I have done on A Year of Positive Thinking these past four years, essentially writing another book, one which, despite the availability of the material on the blog’s archive as long as I maintain the site online, I would love to some day see this material published in hard copy book form, a form which I think still has a gravitas and a usefulness that online material does not.

Trying to find an order of subject matter for a Table of Contents is hard because the blog format, with its capacity for links and pictures and the web’s orientation towards a more diverse range of writing than the strictly or even partially academic has fostered my already marked penchant for associative thinking. Also, parenthetically, blog publishing allows for the immediate accessibility, through links, of material that in a book would be consigned to the endnotes and left to the reader’s enterprise to delve into further. In fact the writing style of the blog posts owe much of its tone and flavor to the kind of more personal and informal writing that I enjoyed salting away into the endnotes of my books. Whereas my two books, Wet: On Painting, Feminism, and Art Culture (1997) and A Decade of Negative Thinking: Essays on Art, Politics, and Daily Life (2009) each focus pretty evenly on feminism, painting, and teaching, the blog has given me the opportunity to comment on political events, write about film, and develop a photo essay format.

In keeping with this fluid, infinitely connected textual and visual frame, this table of contents will put specific posts into more than one section when it seems relevant, in order to be true to the content and to connect to the most readers, true to the web environment of samplers, and surfers, Google and Wikipedia addicted readers of this time. This four year table of contents builds on the one I published two years ago: I’ve kept the first selections intact, added one oddball post I had withheld last time around, and have reordered the categories slightly though it gets harder to contain the material into even the loosely defined categories I had selected two years ago–Art (painting and sculpture) [this specification is deceptive since I write about video, installation, and other forms of art, but just having a heading “art” would seem too general], Feminism, Women Artists, Politics, Teaching, Film, Conditions of Writing a Blog, Oddball, Studio Practice, and Family, or The Schor Project. Within each section, the posts, linked for instant accessibility of course, are listed in chronological order with a little summary of the subject and an occasional excerpt. This table of contents does not contain links to named people and events, these exist within the posts themselves.

I have bold faced some of the posts that I reference the most frequently when discussing the blog.

One technical point: some of the posts contain embedded film clips from YouTube but over the years some of the clips are no longer available due to copyright issues but I have left the embeds in place, as markers whose emptiness may perhaps serve as enticements to try to see the film in question by some other means.

Preface: “About”

Introduction: Looking for art to love in all the right places (April 28, 2010)

I’ve fallen in love with many more artworks than I have men and without giving anything away I’d have to say that I’ve had better luck with the artworks I’ve loved and even the ones I’ve hated. No painting I’ve ever seen was married or loved someone else, or got in the way of my need for independence or solitude, and if I’ve tired of a work, having taken from it all that I needed and then outgrown it, the parting has always been amicable with the possibility of hooking up again always open to me. Meanwhile, and you can fill in the personal analogy or not, I pay a lot of attention to works I really dislike and get a lot of energy for my own work as a result.

Art (painting and sculpture):

Reality Show: Otto Dix (June 28, 2010) I’ll let one of my readers sum this one up:

I’ll confess, when I saw the tweets start flying about Mira Schor’s essay on Otto Dix, Greater NY, and Bravo’s Work of Art, I was skeptical. How the hell was she gonna fit any of those, never mind all three–at once–onto a blog called A Year of Positive Thinking?

By gum, she pulled it off.

Otto Dix, a brief footnote: drawing and ideational aesthetics (July 5, 2010)

Under the circumstances, I was struck by the speaker’s use of the word “ideation” as a substitute for the word drawing. It stuck in my head partly because it is sort of a cool word, with its pseudo-scientific and vaguely military/corporate buzz. On the other hand it’s somewhere between annoying and sinister in its implications to art making.

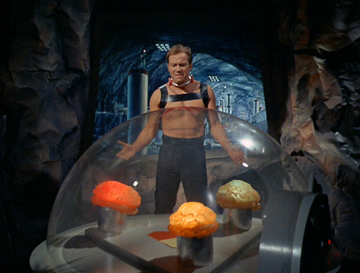

Postcard post (August 8, 2010) In this set of virtual postcards to my readers, I write about some of my favorite works of art and works of popular culture, including Andrea Mantegna’s The Dead Christ, the sculptural program of the North Portal of Chartres Cathedral, Giotto’s frescoes from the Scrovegni Chapel, Star Trek, and Buster Keaton.

Anselm Kiefer@Larry Gagosian: Last Century in Berlin (December 24, 2010) The forcible eviction of a few peaceable demonstrators by the NYPD from the Kiefer exhibition at Gagosian Gallery in December 2010 was the spur to consider aspects of this body of Kiefer’s work with its inflated production values and questionable arrogation of Judaism.

Above the entrance of a vast space occupied by a German were letters written in black script. In transliterated Hebrew and English, they spelled out “Next Year in Jerusalem,” the concluding line of the Passover Haggadah. Next Year in Jerusalem? My hackles were officially raised even before I turned the corner and entered the occupied territory of Gagosian Gallery. I still don’t really want to write about Kiefer, so here is just a précis. The installation reminded me of nothing so much as Bloomingdales’s cosmetics floor if its Christmas decorations had a Holocaust theme.

The fault is not in our stars but in our brand: Abstract Expressionism at MoMA (October 3, 2010)

This led me to think about the work through the lens of the Brand. At first this seems to contradict approaches to art-making that are characteristic of the period, such as the picture plane as the arena of existential search. But of course most of the artists in the first two generations of Abstract Expressionism became known for a particular stylistic brand: drip (Pollock), zip (Newman), stroke (de Kooning), chroma (Rothko). Here then are some major case histories from the main exhibition.

Money can’t buy you love but art friendships can create joy (February 6, 2011) This post, about the exhibition “Poets and Painters” at Tibor de Nagy Gallery, allowed me to consider the joyful and creative network of friendships among artists including Rudy Burckhardt, Yvonne Jacquette, Edwin Denby, Alex Katz, Mimi Gross, Red Grooms, Joe Brainard and Ron Padgett, John Ashberry, James Schuyler, Frank O’Hara, Jane Freilicher, and Larry Rivers, among others.

There is a particular kind of collaboration among artists who are friends that is special because it takes place outside of the frame of the art market, often before each individual’s path is fixed and their fate is determined, that is before some become rich and famous, while others struggle along, and still others die or vanish from the scene into another type of life than the one of the artist. Such moments are nearly impossible to sustain, but it can be pretty conclusively proven that these are often the happiest times in the lives of these artists and often too those artworks that later are seen to have the greatest market value emerge from just these moments of friendships and creative projects undertaken in relative conditions of anonymity, for the sheer joy of making and the pleasure in shared ideas.

Wonderment and Estrangement: Reflections on Three Caves, parts 1 and 2 of 3 (July 28, 2011) & part 3 (August 18, 2011) A consideration of three caves, the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc cave featured in Werner Herzog‘s Cave of Forgotten Dreams, the cave inside a malachite mine deep in the Ural Mountains featured in a 1946 Russian children’s movie The Stone Flower, and the cave whose entrance lurks in the shadow of Giovanni Bellini’s St. Francis in the Desert, which was on special display at the Frick Museum in New York in the spring of 2011.

You may once have had experiences of wonderment and delight, perhaps most uniquely in childhood, in your imagination, reading a book, hearing a story, or seeing something of incomparable beauty. You’d think being an artist would give you continued access to such experiences but for the most part life as a professional artist is at best a negotiation among the constantly changing realities of contemporary art, the limitations of one’s own abilities, and some internal core ability to still experience such wonderment when it presents itself, despite competitiveness, jealousy, and the infrequency of such experiences. Basically we once experienced wonderment and now we do the best we can. So when we do on rare occasions experience wonderment or delight, it is notable, and for a moment we may return to the prelapsarian intensity, awe, and joy first experienced in childhood and which is part of the secret fuel for a lifetime of art practice.

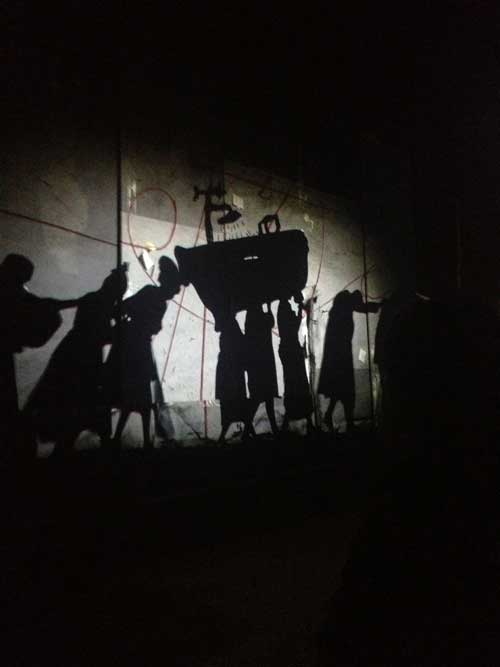

Art of the Occupy Wall Street Era (October 12, 2011) On Creative Time curator Nato Thompson’s exhibition, Living as Form

Youthfulness in Old Age (December 8, 2011) On expansive creativity in old age, exhibitions of later works by Joan Mitchell, Richard Artschwager, and Matta.

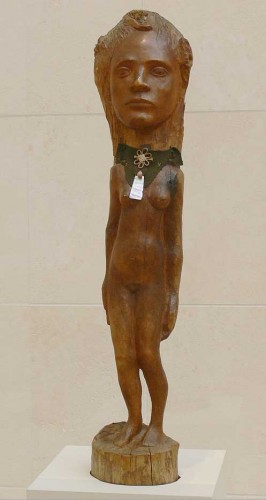

You put a spell on me (January 1, 2012) on two extraordinary exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Renaissance Portrait from Donatello to Bellini and Heroic Africans: Legendary Leaders, Iconic Sculptures.

As a teacher, I’m interested in how one can use art or artifacts that may seem inaccessible or irrelevant because they were made in ancient or foreign cultures seemingly alien to our own and also because works like these African sculptures or Renaissance paintings seem to have already been digested, for once and for all by our own history, so that our ability to use them appears doubly blocked. How do you use old art? How do you use any great art while not sinking into preciousness?

A State of Intense Excitement and Apollonian Reserve (October 13, 2012), on an exhibition at the Morgan Library of color studies on paper by Josef Albers.

Three days more to see “Toxic Beauty” (December 5, 2012), on Frank Moore’s exhibition of paintings at the Grey Art Gallery and of sketches and videos at the Fales Collection, in relation to the endlessly recurring narrative of the death of painting.

That the narrative of the death of painting is still ongoing should be evidence at the very least of painting remaining a naggingly persistent ghost, or not even a ghost but a kind of zombie entity, not quite dead enough to go completely unmentioned. It continues to appear if only as a negative, as something that cannot be done…. At one point last spring it occurred to me to write a series of essays on the theme of When Exactly Did Painting Die? Not exactly a murder mystery, you see, not a Whodunit but rather a What Was the Time of Death mystery, or, maybe, When Was the Victim Last Seen Alive? mystery.[…] (In Moore’s 1994 painting Easter) Blood seeps out of two slices into a loaf of bread and into the middle of a puddle of spilled heavy cream which has oozed out from an overturned cartoon. The red paint has been dropped into the pool of white paint to create a very careful Jackson Pollock in the shape of a Crown of Thorns. The Christ reference and the art reference are at the center of a still-life painting with an almost folk art sensibility: the dusting of flour on the loaf of bread is created with a kind of spray effect which is completely different in technical feel than the loaf, or the cream and blood spill. It’s a folk Zurbaran of the AIDS era.

Catching up by playing hooky: Bernini, Shea, Cage, and Picasso (January 1, 2013), at Picasso Black and White at the Guggenheim,

By the time I got to the middle of the ramp, before I even got to a painted sketch for Guernica of the screaming horse’s head, I wrote in my notes, “I would say, at this point, fuck it, this is a necessary show, don’t tell me you’re a painter or interested in painting and not see this show, forget what you know or think you’ve seen, or think you know about Picasso, and just look.” That I would be so emphatic seems silly given Picasso’s totally accepted status as a genius, but it reflects the fact that for many artists Picasso’s relation to subject, to medium, and to drawing, is as foreign as the back side of the moon.

Resisting Pier Pressure (March 10, 2013), this post epitomizes what I intended when I began A Year of Positive Thinking, the pleasure of discovering art works that I love, including a group of small clay reliefs by an artist I had never heard of before but whose works I have thought of often since I first saw them.

What does a man see when he looks at his own image? (April 12, 2013), on a very particular and powerful instance of the female gaze, in paintings by Susanna Heller.

The living and the dead: Wool, Motherwell, Kelley, and Kentridge (January 1, 2014), Abridged version: Christopher Wool? Not a fan. Longer recap: Motherwell? Not a fan either except when I occasionally am. Kelley? “…you can admire an artist tremendously, feel strongly that he is an important artist, and still not “love” his work. That is the case for me with Kelley. But love is probably the wrong word anyway to address work driven by a powerful undercurrent of abjection and self-loathing, from some of his earliest performances to the scenarios of the massive video installation work, Day is Done.” I manage to weave Star Trek, Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal, and Italo Calvino’s Italian Folk Tale “Quack! Quack! Stick to My Back!” into this post.

Intimacy and Spectacle 2: answering a questionnaire about contemporary art museums (January 19, 2014) News of MoMA’s destruction/expansion plans happened to coincide with a request from a graduate student in cultural management at the University of Madeira to answer some questions about the contemporary museum.

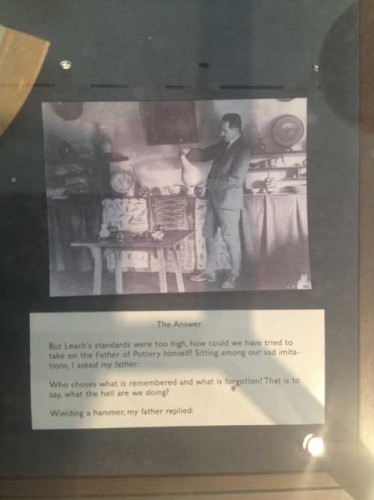

As a sub-theme to this section, one thread that runs through several posts is the importance of drawing as a way to apprehend the world. Several posts feature my love of drawing, including works by Philip Guston and Otto Dix, and the importance of drawing to my own art practice becomes a practical tool to circumvent institutional prohibitions of photography in special exhibitions, in posts such as Otto Dix, a brief footnote: drawing and ideational aesthetics, Looking for art to love in all the right places, You put a spell on me, and a post about The Mourners at the Metropolitan Museum, Looking for art to love, day two: uptown from May 1, 2010 as well as in Catching up by playing hooky: Bernini, Shea, Cage, and Picasso. More recent posts that feature drawing are Hurtling through life at a deliberate pace: an appreciation of Richard Artschwager (1923-February 9, 2013), A Drawing, inspired by the discovery of an ink on paper self-portrait drawing by my father Ilya Schor, Craft and Process: Jasper Johns/Regrets, and the series of posts on my own work from the summer of 2013 Day by Day in the Studio.

Feminism:

Two early posts were related to the Modern Women project at MoMA:

Stealth Feminism at MoMA (May 16, 2010)

On gradually realizing during a random visit to the museum that individual works by women artists and small shows of works by women artists were scattered throughout the museum, like treasures in a treasure hunt that has not been advertised as such.

MoMA Panel: Art “Institutions and Feminist Politics Now” (May 23, 2010)

A recap of a day of panel discussion held at MoMA, held May 21, 2010, as part of their Modern Women Project.

According to Roxana Marcoci, Curator, Photography, these curatorial discussions and initiatives emerged from a desire for greater transparency within the institution; she described the participants’ organization as non-hierarchical and cross-generational. The nature of this feminist work had forced departmental boundaries to be breached as researching work by women forced a greater transdisciplinarity. …

This question of permission is both the positive and negative side of the whole story: better to get the permission — which can only come from an activism brewing from below anyway — than not get the permission. But any freedom or rights based on patriarchal noblesse oblige or realpolitik can be withdrawn when it serves the institution, which is why continued vigilance and activism are always necessary. Some might take issue with the idea that it is better to get that permission and get some feminist action in a dominant institution such as MoMA but I think it all has to happen all over all the time and over and over again (over and over because feminism has tended not to have a good institutional memory, even if you take into account that we live in an ahistorical time).

A Great Artist (on Louise Bourgeois) (May 31, 2010), written the day Louise Bourgeois died.

Sometimes an artwork hedges its bets, or, by some minute concession to accessibility, in some tiny betrayal of form, apologizes for itself. I never detected that in Bourgeois’s work.

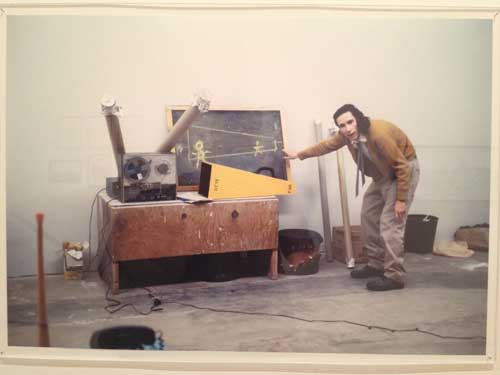

Stephan von Huene, Feminist Teacher (September 4, 2010) written about my mentor at CalArts, with whom I studied after I left the Feminist Art Program.

Biographies of Women Artists: Instinct and Intellect (July 10, 2011) Some thoughts about Lee Krasner, on the occasion of a New York Times book review of Gail Levin’s biography of the artist.

“I’m 27 and Unmarried…” 40 Years later (October 10, 2011) I use a piece written by my sister Naomi Schor for Glamour Magazine in 1971 to reflect on the early years of the Women’s Liberation Movement and how some of contradictions and societal imperatives of that time may still exist despite many advances for women in the United States.

A Feminist Correspondence (December 9, 2011) This post republishes my appreciation of British feminist art historian and psychotherapist Rozsika Parker from November 22, 2010, with a more recent quite extraordinary correspondence this post initiated, between me and Parker’s collaborator, the art historian Griselda Pollock.

In your blog you rightly captured what it was that Rosie gave us and me in terms of making me a feminist writer on art: that things mattered deeply and seriously and that art touches on things that matter to us as we live them. That was what saved me from a bloodless and remote art history which I still cannot inhabit. (G. Pollock)

A Discussion on Facebook About Feminism (May 21, 2012) This post picks up on the epistolary nature of “A Feminist Correspondence,” but transposes the format of emailed letters to a Facebook conversation, of the kind that occasionally make that off corporate space a platform for community and discussion among people who are not in the same room and who may or may not have ever actually met. I had posted on Facebook a link to a New York Times editorial, “The Campaign Against Women,” with the query “Is there still a need for “Woman”-focused feminism or would other theories and political positions be more useful?” The discussion that ensued is one that is all the more pressing for being so familiar, but expressed with informed passion by all the participants (who agreed to have the conversation republished on the blog). I have participated in many such conversations on Facebook as it seems that issues surrounding feminism remain perpetually pressing, perpetually unresolved particularly to the women artists who are my interlocutors as well as to men who take an interest in the subject and feel concern for their women students as they begin to grapple with these issues.

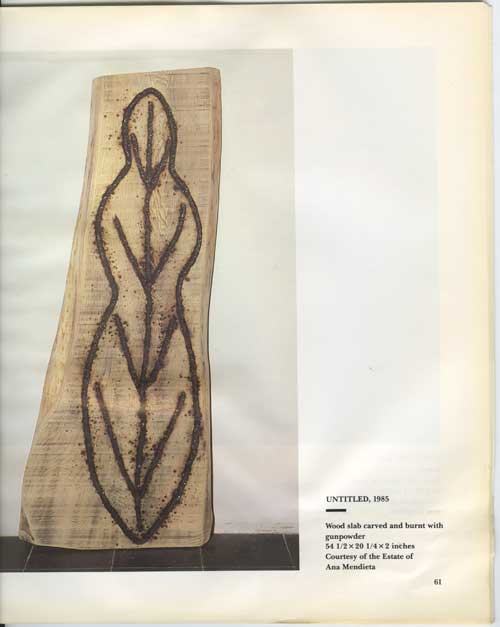

Women Artists:

Since there is much contestation over the designation feminist and in order to make access to posts about individual artists easier, I thought I’d create this separate category, of the notable posts on specific women artists.

Looking for Art to love–MoMA: A Tale of Two Egos (May 8, 2010)

“Marina Abramovic: The Artist is Present” is itself a tale of two egos: downstairs, that of the individual living woman whose body you can witness and potentially engage with at some level, and, upstairs, the projected ego of the woman who has hijacked curatorial common sense, whose many incarnations are screaming at you in an unpardonably cacophonous, unedited installation, who has created a kind of Disneyworld of the Spanish Inquisition through her use of re-enactors in stressful situations while rewriting the history of performance art so that she exists sui generis, without any historical context.

A Great Artist (on Louise Bourgeois) (May 31, 2010)

A Remembrance: Sarah Wells (June 6, 1950-June 6, 1998) (June 6, 2011) On the work of a wonderful artist and a wonderful person, a dear friend exactly my age, who died too young, on her birthday.

Biographies of Women Artists: Instinct and Intellect (July 10, 2011)

On Being a “Lady” (February 10, 2013) was my solution for how to review a show I was in, “since the show is divided into two parts, installed along two separate sections of the space, with one side featuring the works of women artists who are deceased, and the other side featuring those of us still among the living, I feel that I can safely recommend the dead without incurring controversy among the other living artists in the show or referring to my own work in it or the ramifications of the word “lady, ” which I know has stirred some controversy.” This is a brief review but provides the occasion to highlight some wonderful art works by artist such as Alice Neel, Alma Thomas, Irene Rice Pereira, Edith Schloss, Louise Bourgeois, Ruth Asawa, and Janice Biala.

What does a man see when he looks at his own image? (April 12, 2013)

Politics:

My Whole Street is a Mosque (August 19, 2010) This piece was written when there was a media furor over the plans to build a mosque near Ground Zero and it occurred to me how absurd this was when the street that I lived on in Lower Manhattan, Lispenard Street, effectively was an outdoor mosque, when men pray on the sidewalk several times a day. This blog post ended up on The Huffington Post and was one of my few experiences with going viral, in a very modest way.

Confessions of a Yellow Dog Democrat (October 21, 2010) Attempting to reconcile my own profound disappointment at the timidity of Democratic party politicians with the reasons I could for many years call myself a “Yellow Dog Democrat,” I tried to cram as many references with as many links to as many great moments in American history, some which I witnessed, some which I already experienced as legendary, as I could, in order to give younger readers a sense of why anyone would still identify with a political party or regret no longer identifying with it.

This Past Week in Activism: Three Modest Gestures (December 12, 2010) How Manet’s The Execution of the Emperor Maximilian of Mexico, 1868, at the National Gallery in London, becomes a potent witness for a teach-in of students protesting the tripling of educational fees by the Cameron Government, and other valiant political gestures.

Should we trust anyone under 30? (with some excerpts from “Recipe Art” and other essays (June 20, 2011) Concerns about generational reversals, as observed before Occupy Wall Street.

Somebody Had to Shoot Liberty Valance (September 18, 2011) The relevance to our current political dilemmas of John Ford’s late masterpiece The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, a starkly simple, cinematically almost archaic yet profound meditation on the role of violence in creating the American democracy and on the nature of history itself.

Art of the Occupy Wall Street Era (October 12, 2011)

A Discussion on Facebook About “Occupy Museums” (October 19, 2011) A topical example of the kind of Facebook discussion thread which at its best is a new form of group authorship. Bonus: photos of a 1984 demonstration outside the renovated MoMA to protest the lack of women in the inaugural exhibition.

“Books are like people” (November 15, 2011) The destruction of the People’s Library by the NYPD seen through the lens of art historian Leo Steinberg’s remembrances of the signal importance of books during his childhood as a young refugee in Berlin and London.

Where the Fuck Was Edward Albee? (May 8, 2013), I return to the politics of eradicating books, in this case the horrendous plan hatched during the regime of Mayor Bloomberg to gut the stacks and remove the books from the main branch of the New York Public Library at 42nd Street.

“amazing!” (October 13, 2012), on the jarring aspects and political implications of the style of presentation of talks at the 2012 Creative Time Summit in New York City in relation to the content of specific artworks and subjects. This was a post that seemed to touch a nerve and went semi-viral.

the Creative Time Summit’s first day was marked by a relentless positivism embodied in its chosen style of presentation, a style derived from the equally relentlessly positivistic and corporatized TED Talks. […] The word “amazing” was used liberally, notably by the organizers. Many of the speakers were indeed AMAZING but it is a crucial semiotic point that this style and format, enabled and dictated by the available technology, comes to the university and art world from the corporate world, in the Steve Jobs super salesmanship genre, thus they carry political DNA from these sources while other methods of presentation and thus of knowledge and political valence are suppressed.

Teaching:

All my writing is an extension of my deeply felt vocation for teaching but some texts specifically address conditions and specifics of teaching art.

Teaching Contradiction: Reality TV and Art School (August 27, 2010) On contradictions that exist within the expectations placed on artists studying in MFA programs around the country, as suggested by the end of the first season of the Bravo Network reality show “Work of Art: The Next Great Artist.”

While working on a syllabus on a winter’s afternoon (January 17, 2011) Listening to “A Beautiful Symphony of Brotherhood: A Musical Journey in the Life of Martin Luther King, Jr.,” while planning a syllabus including works and writings by Guy Debord, Michel de Certeau, John Cage, and Simone Weil (& see also Should we trust anyone under 30? to learn more about what happened in that class.)

Free Speech (October 2, 2012) noted a number of events in the fall of 2012 exploring alternatives to current educational institutions, including the Free University’s open air classes held in Madison Square Park September 21, 2012.

Film:

Magic Tricks in the Dark (May 14, 2010), on William Kentridge‘s installation of 7 Fragments for Georges Méliès

In the Wave (May 20, 2010) a comparative appreciation of the films and the artistic friendship of Francois Truffaut and Jean Luc Godard, inspired by Emmanuel Laurent’s documentary Two in the Wave.

Money can’t buy you love but art friendships can create joy (February 6, 2011) This post includes an appreciation of Rudy Burckhardt’s films including Money, (1967), his first feature film of his 200 or so films, with script by Joe Brainard, about a money mad billionaire played by Edwin Denby, a film which combines a goofy, spontaneous home movie feeling (with actors including the artists Red Grooms, Mimi Gross, Yvonne Jacquette, Neil Welliver, Rackstraw Downes, as well as these artists’ children, Jacob Burckhardt, Titus Welliver, and Tom Burckhardt–now all adult artists engaged in film, acting, and painting).

Somebody Had to Shoot Liberty Valance (September 18, 2011)

Wonderment and Estrangement: Reflections on Three Caves, parts 1 & 2 (July 28, 2011) a post inspired by Werner Herzog’s film Cave of Forgotten Dreams and my rediscovery of the 1946 Soviet era children’ film, The Stone Flower.

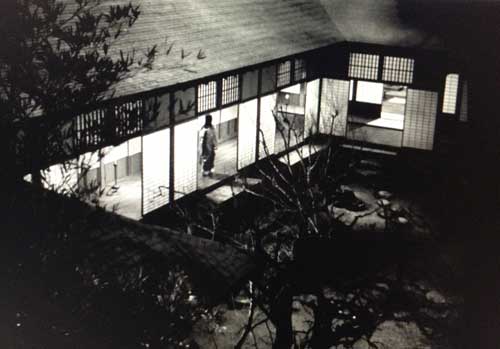

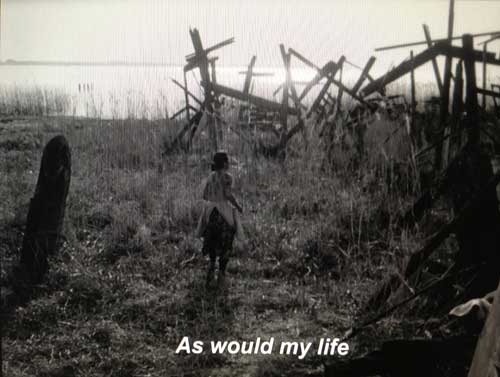

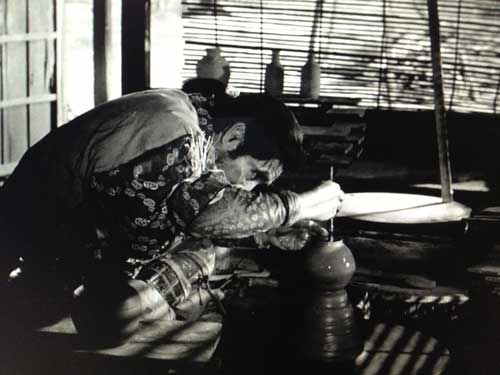

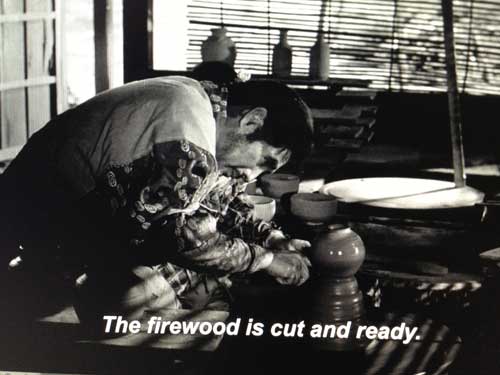

Craft and Process: “Mingei: Are You Here?” and other ghost stories (April 3, 2014), a show of contemporary art and traditional Japanese folk objects reviewed through the lens of an analysis of the allegory of creativity in Kenji Mizoguchi’s great 1953 film Ugetsu.

Conditions of Writing a Blog:

Three blog posts from the summer of 2011 examine the conditions of contemporary web publication and readership, centered around instant readership tracking mechanisms such as Google analytics, and their effect on what gets written about, and the increasingly compressed time available for elucidation of artworks and events, in relation to earlier forms of hard copy small journal publications, with a post devoted to two essays by John Berger, “The Moment of Cubism” and “The Hals Mystery.”

Invisibility and Criticality in the Imperium of Analytics (July 31, 2011)

The Imperium of Analytics (August 2, 2011)

The Berger Mystery (August 11, 2011)

Odd ball

“Miss Read” (April 14, 2012), an obituary in the Times reveals the identity of a writer whose book I read on a train during one of the strangest yet most memorable evenings of my life.

Studio Practice:

In the summer of 2013, I hijacked A Year of Positive Thinking for a slightly separate project, Day by Day in the Studio: I posted selected works I had done on specific calendar days from forty-three summers as an artist and discussed many of the topics relevant to this Table of Contents: family history, teaching, drawing, craft and process, feminism, and I reflected on a spectrum of influences and studio conditions, down to the very tables I work on. This was a personal project and provided the opportunity to situate statements about specific works within the complex forces that underlay any art work but I also tried to discuss themes that would have broader interest to readers who were artists themselves or interested in how artists work. This project was helpful in developing the work I was doing as I was writing about it, with the final post suggesting the title I used for an exhibition of paintings held in Los Angeles in October 2013, Chthonic Garden.

There were fourteen posts in all in this series: some contain mostly images of my work from the 1970s to the present with very little text, so the ones I have selected are among the more developed texts.

Day by day in the studio 1: July 13 (July 13, 2013) I introduce some of the rhythms of my studio practice, and some of the recurring anxieties about productivity.

As my friends can attest through forty years of listening to me wail over the phone about how I’m not working, the work isn’t going well, that I know I always say that but this time it’s really bad, no amount of experience and of tricks I’ve successfully played on myself in the past mitigates the sense of despair that overwhelms me, even as, as it turns out a few weeks later, I was and am in fact “working.” I’m despondent until a moment when I feel a sense of access to the work, where I both feel that I am working and that I can see the work I am doing without its already being historicized within my own process.

Day by Day in the Studio 2: July 14 (July 14, 2014) on my use of different kinds of translucent, delicate paper and my habit of working on both sides of the paper.

Day by Day in the Studio 4: July 16 (July 16, 2014) I have written about the phenomenon of “Trite Tropes” and “Recipe Art,” here I take note of my own early work with various trite tropes including tropes that weren’t quite so trite when I first came to them:

The dress is long since a trope of feminist-inspired art but at the time it was not that prevalent, and there was not so much of a leader/follower situation as that it was a moment when a range of subjects and materials from women’s daily lives and personal experience were newly available to women artists of a range of age and experience.

Day by Day in the Studio 5: July 17 (July 17, 2013), on the tricks one plays on oneself to get past work block.

Day by Day in the Studio 8: July 30 (July 30, 2013), about illusions of both subjectivity and objectivity on the part of the artist. I examine the arc of my relationship to critical theory since the mid-1980s:

The conflict I have indicated between work that remains responsible to/restricted by critical/theoretical concerns and work that would be free to engage with visual pleasure in a less mediated way is itself an unreliable portrait of “myself.” I can’t possibly separate the intellectual from the visual. Even when I stick my nose in the earth, I’m doing it because I’m inspired by a text I’m reading.

Day to Day in the Studio 9: August 1 (August 1, 2013) A work from 1984 invites a consideration of past and future, the sudden disappearance of essentials of studio practice including specific art supplies (an ongoing topic of discussion among artists “who use art supplies to make art” as a friend recently described it), and considerations of how the future may affect our present labor.

Reading predictions of the future can make you wonder about what you work so hard to accomplish in the present. For example I put a great deal of effort and resources into trying to preserve my parents’ work and histories, as well as my own artwork, but if New York is going to be largely underwater in fifty to a hundred years, as some studies predict, so will its museums and libraries, so maybe I shouldn’t bother.

Day by Day in the Studio 10: August 3 (August 3, 2013) on working equally on the front and the back of paintings, drawings, and even of frontally oriented bas-reliefs and sculptures, in my work and that of my parents Ilya Schor and Resia Schor, and on my reacquisition of a book on Rajput Painting that had been very influential in my formative years as an artist, before I went to graduate school. I had to order a new copy just so that I could check my memory of this line of 16th century Indian poetry:

This night of rain and rapture, all Vrindavana/ unmoored, adrift, lost in the solid dark of rain/ in torrents of sweet rain.

Day by Day in the Studio 12: August 11 (August 11, 2013), about the stability of work tables over decades.

Day by Day in the Studio 13: August 15 (August 15, 2013), I consider “how much, practically speaking, it takes to get anything, however modest, done as or for an artist, how much psychic energy it takes to believe in artworks and to make others believe in them, particularly the degree of intensity of belief that at least one person must feel for artwork in order for it to survive after an artist’s death.”

Day by Day in the Studio 14: August 24 (August 24, 2013), on a word to describe the content of recent paintings,

This week I have fallen in love with a word, the word Chthonic …. How do we fall in love with words these days? I clicked on the link in the Wikipedia entry for Persephone, and , at 2AM, having finally torn myself away from gazing at the definition on the screen, I jumped out of bed to go and gaze at the Wikipedia page some more…Chthonic, “it typically refers to the interior of the soil, rather than the living surface of the land.”

In three recent blog posts I have continued to explore the importance of studio process and of craft, in response to situation where access to such aspects of art making is impeded by ideology and circumstance.

Craft and Process: Jasper Johns / Regrets (March 25, 2014),

I am interested in the capacity of material experimentation and serial practices to bring an artist to the expression of, the performance of, the actualization of content the artist had intended or desired but might not have arrived at if trust had not been put into process and materiality at some point or another.

Craft and Process: “Mingei: Are You Here?” and other ghost stories (April 3, 2014), continuing my interest in “an approach to art making that acknowledges the equal importance of making and thinking and I’m committed to the idea that there is a richness of intellectual content inherent in materiality and process,” I review a recent show of contemporary art and traditional Japanese folk objects through the lens of an analysis of the allegory of creativity in Kenji Mizoguchi’s great 1953 film Ugetsu.

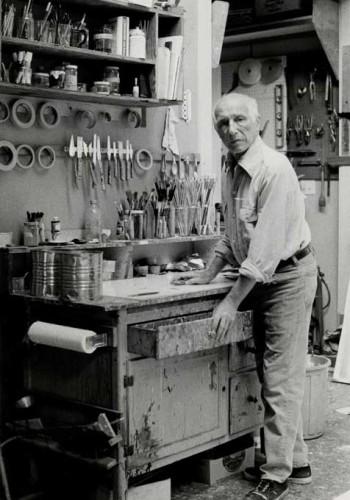

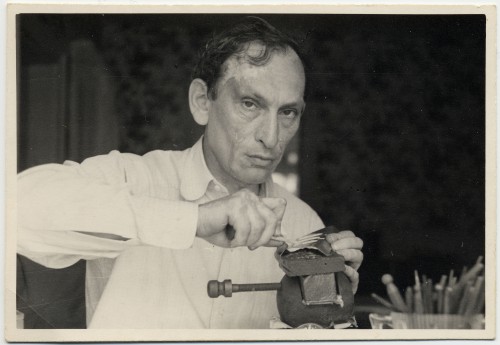

Craft and Process: Tools and “wild ‘reserves’ for enlightened knowledge” (April 116, 2014) a beautiful old work chair in the studio of Chaim Gross opens up a consideration of tools and craft, the pleasure I take from watching things being made by hand, and my belief that there is “an intelligence in the craft, in the gesture.”

Family, or “The Schor Project:”

These texts form the nucleus of a project to which I am deeply committed, a cultural autobiography into which I would fold my parents’ lives and artworks and the influence of my sister’s work as a scholar and a feminist. This project would rely on archival images and on artworks, it might take the form of a book, but the blog posts have suggested the format of the photo essay, either still in book form or as photo- and text-based artworks. These posts may seem also like a hijacking into personal territory but if the goal of A Year of Positive Thinking was to turn my attention to the art work that sustains and inspires me, this goes to the core.

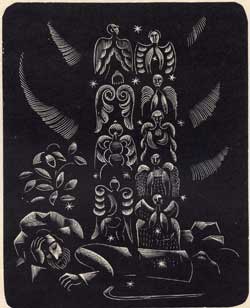

For Father’s Day: Ilya Schor (1904-1961) (June 18, 2010), a celebration of my father Ilya Schor’s work, featuring some small paintings made in Marseilles, France while my parents awaited a visa to America.

“I Love You with All My Hearth” (December 5, 2010) an appreciation of my mother Resia Schor’s work, published on what would have been her 100th birthday:

That my mother as a person had sought economic survival through her own aesthetic labor was already a lesson in feminism for me and my sister. And, as she developed her own style and techniques in her new medium, it became intriguingly clear that my parents’ work embodied a strangely crossed gender art message that in itself contributed to my sister Naomi and my involvement with feminism and perhaps too to the slightly unusual flavor of our feminist outlook. Inasmuch as art movements are gender coded, my father’s work — folkloric, figurative, narrative, Jewish, delicate, light in weight — carried a feminine code. My mother’s work, abstract, muscularly sculptural although still relatively small in scale but heavy in weight carried a code that would seem to be masculine, as those terms are used.

Orbis Mundi (April 24, 2011) An essay prompted by a major move and the resulting intimate contact with my family’s archival ephemera and their collection of art objects, including a mysterious ceramic ball with Christian liturgical associations, which lays the path for my future project of writing an artistic autobiography in a photo essay format.

So I have bucked an American axiom, that you can’t go home again. I have returned to the building I was born into, and to the beautiful apartment I moved into when I was five–the day I first saw the apartment with my parents, taking the elevator from our smaller apartment a few floors below, is the moment where my conscious memory truly begins. Thus infuriating circumstances have precipitated my taking on part of what I consider my destiny, that is to archive and to mark as best I can the memory of my family’s life, particularly my parents’ lives in Warsaw and Paris before the War, their escape from Nazi-occupied Europe, and their creative life in New York as the background for the path I have taken in my life as what I would call an inflected American.

“I’m Unmarried and Single…” 40 Years Later (October 10, 2011). On my sister Naomi Schor’s birthday, I begin a task I hope to continue, of writing about her via the magazines she collected over the years, to address her intellectual life through the popular culture she loved and the political events we lived through together, rather than through her notable work as a feminist theorist and scholar of French Literature and psychoanalytic theory, a body of work too daunting for me to address effectively.

A Drawing (March 26, 2013). Reaching into a closet in my family apartment has a cave of Ali Baba aspect: you reach in, grab at something that looks like scrap paper, and lo and behold there is something beautiful, here a self-portrait ink drawing by my father.

I was born: Past, Present, and (June 1, 2013) “As I first became an artist, I began to consider some of this burden of memory. Now I am used to it, that burden is my destiny.”

Naomi Schor at 70 (October 10, 2013), to celebrate my late sister’s birthday, “some of her many books and articles that are of continued interest, both for her original theoretical insights, her perceptive and nuanced writing style, and also, as traces of the theoretical and linguistics styles that mark developments not just in her work but in the fields within which she worked, from French Literature to Feminist Theory to Gender Politics to Aesthetics.”

*

Although it would seem that I should set aside A Year of Positive Thinking in order to more fully develop the project of writing such an artistic autobiography, I am reluctant to do so because it is hard to give up any space for public speech, even if, as a self-published blog with a modest readership, I am speaking while standing on a tiny slippery stone in the middle of a vast ocean of media and opinion. So, in the sporadic fashion of the past four years, I plan to continue for a while longer, because there are still some unfinished sketches for posts that I have carried around like my own personal “giant rats of Sumatra,” (“Watson…a story for which the world is not yet prepared”) and because even just the goal of looking for art I love, and the occasional discovery of such work, is a lifelong proposition and can only help expand my cultural life as an artist. The year of a positive thinking is a metaphorical time frame and if it is sometimes quite difficult to maintain a positive outlook in a precarious world, A Year of Positive Thinking retains its uses for me even if only as an aspirational mode of thinking.