The overall atmosphere of Friday’s symposium at MoMA, “Art Institutions and Feminist Politics Now,” was more low key than the 2007 MoMA symposium The Feminist Future: Theory in Practice in the Visual Arts. Although the museum claimed the event was sold out, the auditorium never seemed completely full and the overall sense of buzz was subdued, curbed also perhaps by a certain atmosphere of self-censoring professionalism and politesse that was one of the underlying threads of the event in keeping with its focus on art institutions — art institutions in general and MoMA in particular.

MoMA Curators on the Modern Women's Project, May 21, 2010

This was summed up in the third and last event of the day when eleven women curators and Associate Director of MOMA Kathy Halbreich sat at a long dais, with curator Connie Butler and others joking it looked like the Last Supper. Halbreich quipped that however Judas was not invited! She seems like a big personality, warm and funny, with a little looser sense of how things could be done. She noted that 24 out of the 35 curators at the museum are women. For several years women curators working with the encouragement of the Modern Women’s Fund established by benefactor Sarah Peter have been meeting on a regular and intensive basis to reevaluate the collection, go through the museum’s archives in order to discover what work by women artists the museum does own, seek out the gaps in the collection, target acquisitions, and organize exhibitions of work by women artists in all media in an effort to normalize the display of women’s participation in the history of modern art in an incremental manner rather than in a one-shot total museum square footage WACK! or elles@centrepompidou model, to reassess their own canon on a longer-term basis (see my recent post, Stealth Feminism at MoMA).

According to Roxana Marcoci, Curator, Photography, these curatorial discussions and initiatives emerged from a desire for greater transparency within the institution; she described the participants’ organization as non-hierarchical and cross-generational. The nature of this feminist work had forced departmental boundaries to be breached as researching work by women forced a greater transdisciplinarity. Marcoci said that. before, “departments functioned like Federations,” and Barbara London, Associate Curator, Media and Performance Art, said that before this women’s initiative they were bureaucratized by medium but now there was much more interdepartmental engagement. I wish there had been more time to develop this point further, that is, why looking for women in the collection would impose the necessity to transcend departmental fiefdoms and to what extent now common ideas about collaboration, interdisciplinarity, and the non-hierarchical are part of the legacy of feminism’s critique of monolithic patriarchal power. Marcoci also noted that the curators involved in these weekly meetings “didn’t have the power of governance but of thinking,” and that they “created intellectual capital for the institution to redefine canonical narratives.” I think she was the one who said also something funny, that it was no longer a “become like me and I’ll respect your difference” kind of situation but something more open.

The curators noted the importance of Kathy Halbreich’s role in emboldening them in their efforts on this project and in “creating peripheral vision broader than vision.” But Halbreich’s response disclosed part of the problematic of women striving to insert a feminist discourse and investigation into a major institution: she said that when she first arrived she had gone around and asked each person “what do you want to do?” and then, leaning in, “what do you really want to do?” She gleaned from this exercise and reported to museum director Glenn Lowry that there was “a lot of self-censorship going on in this organization, do you want to keep it this way?” She said that he gave permission for her to give permission. That feminist activism is often dependent on permission from a more or less enlightened or benevolent individual or set of individuals in an institution is one of the well-known ironies of the history of feminist art in this country certainly: you have the example of Dean of the School of Art at CalArts Paul Brach inviting Judy Chicago, working with Brach’s wife Miriam Schapiro, to bring her feminist art program from Fresno State (Chicago’s Fresno program enjoyed an aberrant degree of autonomy for a state institution) as well as the counter example of the Women’s Building which Chicago co-founded with Sheila Levrant de Bretteville and Arlene Raven precisely to create an institution where women would do everything and owe nothing to male power or agency.

This question of permission is both the positive and negative side of the whole story: better to get the permission — which can only come from an activism brewing from below anyway — than not get the permission. But any freedom or rights based on patriarchal noblesse oblige or realpolitik can be withdrawn when it serves the institution, which is why continued vigilance and activism are always necessary. Some might take issue with the idea that it is better to get that permission and get some feminist action in a dominant institution such as MoMA but I think it all has to happen all over all the time and over and over again (over and over because feminism has tended not to have a good institutional memory, even if you take into account that we live in an ahistorical time).

Nevertheless, despite the notion of needing institutional permission for feminist activism and clearly having to work within the rules of a large and uniquely important and self-important institution, it was evident that things really had changed in terms of the institution’s sense of responsibility to women artists’ contribution to the history of modern art, in all fields. Here was a cohesive group of highly capable, intelligent, dedicated women who were involved in a long- term concerted development project.

On the other hand there were also indications in the three panels that some things don’t change, that many struggles for and within feminism are ongoing.

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky. Frankfurt Kitchen, Höhenblick Housing Estate, Frankfurt, Germany (reconstruction). 1926–27. Various materials, 8’9” x 12’10” x 6’10” (266.7 x 391.2 x 208.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art.

Even on the panel of curators, I occasionally wondered how much history of feminist art was in play (or how much rediscovery of the wheel in the midst of sophisticated curatorial practice) when the curator of Architecture and Design Juliet Kinchin was speaking about a show opening next fall Counter Space: Design and the Modern Kitchen. The kitchen was a contested site, she said, a space of projections. Her enthusiasm was so great the other curators teased her about it but the first major scene of Johanna Demetrakas’ 1974 documentary film Womanhouse came to my mind, the participants talking in 1971-72 about their consciousness raising sessions on the kitchen as a gender-coded site in preparation for a collaborative installation within the actual former kitchen of the house, during which the diverse and conflicting associations the kitchen evoked were discussed in order to develop artworks: for some it was the site of domestic warmth, for others a locus of primal hostility and danger. The kitchen is a contested site, well yeah …

Robin Welsch et al, Womanhouse, Kitchen, detail, 1972

As further evidence of how little has changed in the world of feminism, several speakers mentioned the continued problem posed by the very term feminism, which mostly boils down to the fact that other people don’t like it, therefore it unfairly ghettoizes women who have the justifiable ambition to be seen as operating on as broad a field as anyone else (the male universal where true success exists). On the first panel, “Collections and Exhibitions,” Camille Morineau, curator of elles@centrepompidou, made it clear that the show was accomplished despite considerable resistance from her male colleagues and superiors. She said that despite the fact that French feminist theory (de Beauvoir, Irigaray, Kristeva, Cixous et al) has been so important outside of France, “the word feminism is still completely taboo in France. ” Thus a certain amount of deception about the goals of the exhibition had to be built in to its planning: in fact, it was a guerrilla process, “a feminist gesture that could absolutely not appear that way.” (As an aside, the show by March had clocked in over a million visitors!). Melissa Chiu, director of the Asia Society, pointed to reluctance on the part of Asian women artists to being associated with feminism or women’s issues, despite clear evidence in their work, at least to western feminist eyes, of engagement with just such issues as well with many of the tropes of feminist art — the body, nudity, woman as sexual commodity, personal experience, domesticity — — not all that different than the many women in the US who will say they are not feminists but who support many of the elements of what might be considered a feminist agenda and certainly no different than all the women in the western world who do not want to be considered feminist or even women artists but just artists.

Tania Bruguera began her talk on that familiar note, “I am not a feminist artist.” Marina Abramovic began her talk at the 2007 Feminist Future with the exact same statement, different accent, so my ears pricked up . But Bruguera walked that statement back and forward in a vivid, smart and funny way. She had the audience roaring with laughter, which is so great and so feminist, just the sheer joy of seeing things as they are and speaking out fearlessly. Her comments and her activism are always contextualized and her presentation of her various decisions was hilarious: she announced that she had developed a list of career rules, the first was that she would never sleep with a curator — big laugh– well she did once in 1995 — bigger laugh; never sleep with married men (a recent decision — another big laugh); would try to acquire power — said she does not want to react to power but create power; would do the work she wanted to do without thinking of what it meant for feminism. She made the decision that it was more important to be a strong feminist woman rather than a feminist artist. She asked all the men in the room to stand up. About 5 guys stood up in MoMA’s largest film auditorium. If they were straight, they should sit down. That left about 2 guys standing. How many were there for other reasons than having worked on the forthcoming MoMA publication, Modern Women: Women Artists at The Museum of Modern Art? I think that left no man standing. “I’ve made my point.”… And she is right about that: for the thousandth time, why is it that most men think anything regarding feminist art is of no concern to them? Since so much contemporary art by men owes such a debt to feminist/women predecessors, in terms of content, form, and materiality, and so much now fashionable institutional critique has its roots in less fashionable feminist critiques of power, the question becomes ever more absurd.

Other good presentations included Catherine Lord’s very interesting statement on queering the classroom. I look forward to this being online, which I assume it will eventually, perhaps on ArtOnAir.org, which archives many MoMA events. However, fair warning, the afternoon panel “Pedagogy and Activism,” on which Bruguera, Lord, and Indian performance artist Sonia Kuhrana appeared was derailed [warning, we’re going negative for a minute] by a performative but, to my mind , manipulative and self-indulgent, action by Michelle Wallace, who was to be the final speaker on that panel, who was not there when her turn came (and the Oscar goes to, —- … awkward silence, anxious whispered discussion amongst the hosts … —- could not be here tonight so the Academy accepts the award for —-) so the audience was treated to a twenty-minute long silent, amateurish Powerpoint presentation about Wallace’s family and her mother Faith Ringgold‘s work, at the exact end of which, surprise surprise, Wallace wandered down the aisle, and was then given the opportunity to ramble on further (she was “late” because she was so moved/upset/something by a show at the International Center Photography that she had overslept — it was 3PM). ..One thing crosses gender borders: the bad boy or girl always gets more attention. Proof of that, some younger women thought it was the best thing. (I walked out briefly but am glad I went back in to hear the curators’ discussion.)

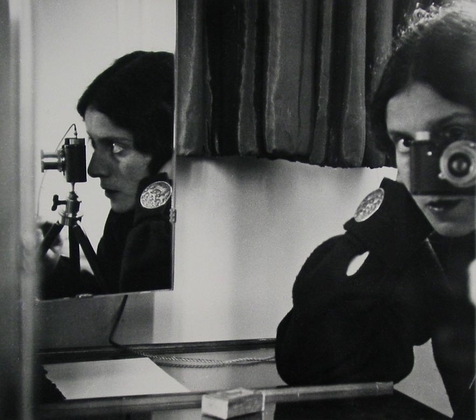

The photo curators had mentioned that for the first time they had been able to organize a comprehensive survey exhibition on the history of photography solely through the work of 120 women photographers in the collection of the Museum, perhaps because from its inception photography was a more democratic medium and thus more accessible to women (and most likely also, because of the relatively lower cost of acquiring photography, easier to acquire in depth particularly in the earlier years of the institution). There are indeed many wonderful photographs representing major movements in the history of photography in Pictures by Women: A History of Modern Photography, including this self-portrait by Ilse Bing, the woman artist in the act of looking at herself looking, owning and refracting the gaze.

Ilse Bing. Self-Portrait in Mirrors. 1931. Gelatin silver print, 10 1/2 x 12" (26.8 x 30.8 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York