This morning artist Noah Fischer posted on Facebook an announcement for Occupy Museums:

Occupy Museums!

Speaking out in front of the Cannons

The game is up: we see through the pyramid schemes of the temples of cultural elitism controlled by the 1%. No longer will we, the artists of the 99%, allow ourselves to be tricked into accepting a corrupt hierarchical system based on false scarcity and propaganda concerning absurd elevation of one individual genius over another human being for the monetary gain of the elitest of elite. For the past decade and more, artists and art lovers have been the victims of the intense commercialization and co-optation or art. We recognize that art is for everyone, across all classes and cultures and communities. We believe that the Occupy Wall Street Movement will awaken a consciousness that art can bring people together rather than divide them apart as the art world does in our current time…

Let’s be clear. Recently, we have witnessed the absolute equation of art with capital. The members of museum boards mount shows by living or dead artists whom they collect like bundles of packaged debt. Shows mounted by museums are meant to inflate these markets. They are playing with the fire of the art historical cannon while seeing only dancing dollar signs. The wide acceptance of cultural authority of leading museums have made these beloved institutions into corrupt ratings agencies or investment banking houses- stamping their authority and approval on flimsy corporate art and fraudulent deals.

For the last few decades, voices of dissent have been silenced by a fearful survivalist atmosphere and the hush hush of BIG money. To really critique institutions, to raise one’s voice about the disgusting excessive parties and spectacularly out of touch auctions of the art world while the rest of the country suffers and tightens its belt was widely considered to be bitter, angry, uncool. Such a critic was a sore loser.

It is time to end that silence not in bitterness, but in strength and love! Because the occupation has already begun and the creativity and power of the people has awoken! The Occupywallstreet Movement will bring forth an era of new art, true experimentation outside the narrow parameters set by the market. Museums, open your mind and your heart! Art is for everyone! The people are at your door!

Day 1, Thursday Oct. 20th: Revised Schedule:

3:00 Meet at Liberty Park

Teach-in about the museums we are going to occupy

4:15 Livestream- read document in front of 5000 viewers.

Occupy the 4 train

5:00 Occupy MoMA

hours: 10:30-5:30

11 W 53rd street New York, NY

Occupy the M3 Bus

6:00 Occupy Frick Collection

hours: 10:00-6 PM

1 East 70th Street, New York, NY

Occupy the 6 train

7:00 Occupy New Museum

Thursdays 6-8 free

235 bowery

Via: Noah Fischer, Occupy Museums organizer.

[For further details see Noah Fischer’s Facebook page or mine.]

***

I found that this proposed action gave me pause and it seemed like a good topic for a Facebook discussion, which it has proved to be. I appreciate everyone’s point of view and engagement in the issues. Because not all my friends are on Facebook at all or look at FB that much, and during the day I got an email from Naeem Mohaiemen about where other than Facebook the discussion could be followed [he noted that as luck would have it will be showing a video at the New Museum during the planned protest]. So I thought it would be interesting to repost the conversation that took place today here, with the permission of my Facebook friends’ who participated, since a monologue on my part without the context would miss the point of the conversation.

This following is the conversation from about noon today to 6:30PM:

Mira Schor: I have some ambivalence about this, I’m not sure why. Yes museums have been sucked into the money entertainment mode with corporate corruption, where edge & marginality either commodified or taken out altogether, and with entrance fees prohibitive to the general public. The trend towards the corporate and the art and entertainment market has been especially damaging to the New Museum’s legacy, and especially hurtful for me as a viewer at MoMA, the favored haunt of my youth, where a private relation to art is now hard to come by (though a private relation to an individual art object is something equally critiqued by the current vanguard of social engagement art)…yet some good work is done there as well. I picketed MoMA when it reopened in 1984 with practically no women in its reopening show (see pictures at bottom of this post from that demonstration), but now I don’t feel a visceral response that this is something I can do even though it might be politic or dare I say it , fashionable, to appear to be at the cutting edge of political rebellion. But I’m open for discussion & would love to hear what some of my friends think of this Occupy Museums gesture

Richard Worthington-Rogers: my favorite targets are banks not museums

Mira Schor: well they are linked, major big city museums’ increased engagement in the out of control capitalism that has infected all parts of life is a tangible problem for all art and I understand that young artists would want to make their mark on that part of the profession

Richard Worthington-Rogers: I understand…perhaps i’m just old school and would rather lob a rock through a bank window than a museum….additionally, if the Koch Bros are funding the opera at lincoln center then action should be taken at the opera NOT a museum.

Amy Sillman: here’s how old I am: I wish they’d spell canon right.

Mira Schor: Amy..I feel the same way about the Bell Hooks poster making the rounds of Facebook with chauvinism misspelled as chauvanism

Mira Schor: re the Koch Brothers and the opera, yes !

Amy Sillman: down w/ the koch bros, but up w/ opera.

Amy Sillman: (i didnt mean that like “i’m down with” but as in, bad koch bros)

Chris Kasper: I’m on the fence too. And I like the issue you raise regarding “rebellion fashion”. I think there is some of that at play here. However, museums have become more and more, extensions of banks and other corporate institutions…Moma and other museums high entrance fees keeps what it has too offer for an audience of a certain demographic ,that excludes blue collar citizens (including many of those with mfas) The coroporate culture in museums is echoed in the fear and intimidatiom common in their employees, and breeds nepotism and sychophants. This extends out to many, if not most artists who have not established themselves yet. While I think some of what you raise is totally valid, I do lean more to liking the occupy museum idea more. With the exception of a less puritanical set of values with regards to having embraced gay culture long before it was fashionable, the artworld is still quite conservative in that it favors white males as who it holds up as successful (this is one issue I agree w J Saltz on). If it is better in the artworld for women and people of color than other industries, it isn’t much better. Especially for the people employed by these institutions. We should’nt pat ourselves on the back for being a progressive field at this point. Ask the mostly men who are moving crates and installing the massive works, or the mostly women at the desks with the pressure to dress way out of their salary level at 17.9% apr how progressive an industry we are.

Mira Schor: Chris what you say is true, interesting, much to think about, and only 24 hours to think about it [actually there is no date set on Noah’s original post]…as for who has critiqued the white male content of museums first best, or with most risk….but yes, no illusions as the progressive nature of the mainstream art world

Brian Sg: occupy art school, the biggest rip off there is

Amy Sillman: hey Brian Sg: did you go to art school? which one? i’m just curious because I teach at an art school (Bard MFA) and i’m not sure if they think it’s the biggest ripoff there is! I’ll ask the students, though.

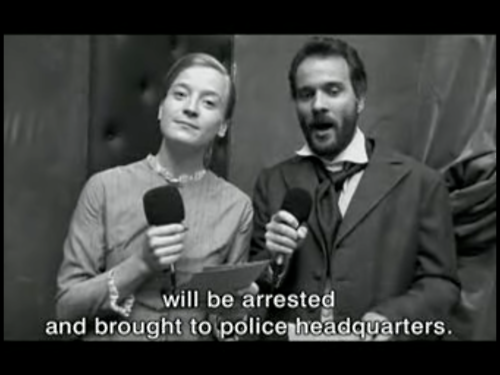

Betty Tompkins: do any of you know the recording about the mccarthy era called “the investigator”? this is starting to remind me of that.

Lori Ellison: Not sure if the museums are the right focus.

Martha Willette Lewis: a lot of museums have suggested donations and I balk at the idea that what they charge (excepting MoMa- that really is extortionate) is too much: going to the movies costs a lot now, cable tv costs a lot , all of these electronic gadgets costs a lot as does wifi- the museums NEED this money. I am sad to see them pander to popular tastes but they are doing it to attract audiences, stay relevant and stay in operation. I don’t think I can support this- museums have given me hours of pleasure, taught me, entertained me. why not “occupy art auctions”instead?they seem much more directly culpable…

Lori Ellison: There was a protest at an art auction several weeks ago.

Martha Willette Lewis: this makes me really, really sad…

Mira Schor: The museums are a probably as legitimate a focus for demonstration as any other in the sense of getting a discussion going..it’s all in the timing. There were people demonstrating against MoMA when the new building opened and the director Glenn Lowry was utterly dismissive of the demonstrators (artists/activists), I can’t remember if he had them arrested or simply mocked them

Amy Sillman: I think since OWS is about BANKS AND MONEY AND WALL STREET as much as anything else, then the suggestion to occupy art AUCTION HOUSES is really interesting!

Betty Tompkins: almost all museums have a free evening. While I admire the energy of the occupy everything everywhere movement, I do have to wonder why they have not focused on governments that allow all this. i also wonder why huge job fairs have not been organized at the park.

Mira Schor: that’s already happened a bit Amy, some demonstrations recently .

Steven Nelson: Museums are intertwined with money and our current corporate mess, but it’s not museums that got us into the economic and social mess we face today. On MoMA admission, it bears noting that one can go there for free on Fridays after 4pm.

Amy Sillman: well, I’m going to stand on my pedestal today and say that what should be occupied is Sothebys, Phillips de Pury, etc. these are places where NOTHING GOOD happens at all. I’d LOVE to go out and protest the whole system of auctioning the work of living artists.

Oriane Stender: This Occupy Museums thing is misguided. It would help if the writer were more articulate. “Speaking out in front of the Cannons”? Beyond the misspelling, what does this mean?

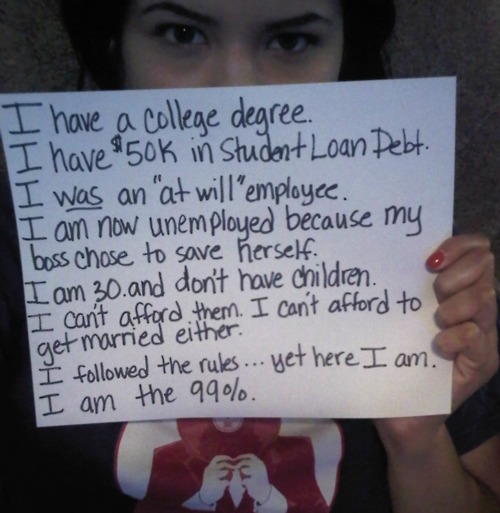

Mira Schor: I think that there is a generation of young artists who were caught up in the intersection between the corporatization of education as of museums, and actually expected to enter the art market and succeed, financially, and I’m sorry were perhaps not sufficiently critical of any part of that. Now they are hugely in debt and of course most artists never make enough from their art or any other profession associated with art to pay back that kind of debt, so they are angry. I was on a panel at Cabinet last year about art education put together by Colleen Asper and Ad Hoc Vox.

The most interesting thing to me that cold winter night was the audience, which was packed to the rafters with thirty-ish Brooklyn-based New York artists, all seemingly wearing black–it seemed like everyone had a two day stubble, also black, and heavy eyeglass frames, also black– fixing those of us on the panel with the most intense and angry expressions on their faces, hoping we would explain to them why their incredibly expensive educations were worth the debt they had incurred.

Art has been just as shaped by the economic boom and the highly reactionary politics of the last 30 years as any other part of our culture. Although I still go to MoMA, I feel like the place where I spent my youth in a close personal private relationship with art works in an intimate space rather than a tourist destination, that space is no more. I’m sorry for those who never had it. Perhaps it is just more of a betrayal when suddenly the rose colored glasses come off and you realize you’ve been sold a bill of goods that can’t sustain you as an artist, literally and spiritually. For me, it helps to have never “believed” in art market essentialism even though that never helped me economically but perhaps that’s precisely why I find this demonstration odd, because it seems to admit to a belief that has been disappointed.

Carol Salmanson: If the target is corporate money taking over museums, then the focus should be corporate money, not museums. Otherwise everyone’s energies will be scattered all over the place, while the corporate money will continue its deliberate and strategic placement, without accountability.

Oriane Stender: I’m not thrilled about corporate money having such an influence in museums, but since arts and culture get so much less government money than they used to get, corporate money keeps the institutions alive, so it’s not altogether a bad thing. It’s complicated. I’d rather the corporations give this money to museums than some other places they could put it, like right-wing think tanks or California’s Prop. 8. Yes, the $ comes with strings attached. There’s no such thing as a free lunch. Etc.

Mira Schor: I don’t know if he will participate here, but Noah Fischer who posted this says he is glad if we are having a discussion, so I think that like everything about Occupy Wall Street, they are taking the chance of acting boldly, if not overtly programmatically, to provoke discussion, and the attention they are getting for that discussion will get media attention that perhaps earlier critiques did not get. The corporate structure and backing of MoMA will not be altered by any demonstration in the long run. I think the New Museum is more ripe for a critique, given the honorable countercultural, counter art market direction of its founding mother, Marcia Tucker, much altered by the cold glitz of the current institution and the amusingly repressive reactions it has on occasion had to internal efforts at institutional critique.

Noah Fischer: Wall Street is a symbolic Altar of Greed: a fitting place to start this movement, but the movement is much bigger than banks and packaged debt and bailouts. To me, its fundamentally about waking up from a bad dream in which our society has lost cohesion- the country doesn’t work for most people- people have forgotten how to work together. And while this has gone on, the wealthiest 1% have walked away with the government..and the culture- witness an era of luxurious art fairs while millions are losing home and jobs. So much about museums today reflects a top-down society where the rest of us are supposed to be mesmerized by the glamour at the top. We Occupy the big museums as both real ties to Wall Street fraud money and as symbols of a culture thats been stolen from the 99% by the elites. When we Occupy Museums, we’ll be announcing and demonstrating a new era of culture that is for everyone.

Noah Fischer: We can Occupy Auctions next week!

Oriane Stender: Re Mira’s observation about the anger young people have about their student debt: Yes, the MFA diploma mill is a giant ponzi scheme. But you are all college-educated and smart people. Did you really think, after the number of people attending art schools kept increasing, that there would be enough tenure track jobs for everyone? Galleries and collectors enough for everyone? This is exactly why I didn’t get an MFA. I did the math (and I’m no math genius). Go into debt to get a degree that a whole bunch of underemployed people have? No thanks. Sorry you drank the Kool-aid, guys. But it was labeled.

Goran Tomcic: If I remember correctly, more then a decade ago there was a huge issue with Whitney and Phillip Morris, i.e. should a tobacco company be a sponsor of the arts. Now we have Deutsche Bank being a major sponsor of Frieze Art Fair, and it had borrowed its name to the Guggenheim in Berlin: Deutsche Guggenheim even has a bank logo on the building facade. I recently closed my Deutsche Bank account as I felt I was not treated correctly and because the bank sucked a lot of money from me in enormous fees just to keep my debit account open. I moved to another bank with less fees and now I am not one of those sponsoring Frieze or Deutsche Guggenheim. As per art schools, I think this is a misplaced call for an action: I went to the above-mentioned Bard MA program and didn’t have to pay as there are scholarships, etc. I believe the art schools need to be left out of this story.

Mira Schor: Noah et al, I’d like to recommend people take a look at the information about The Woman’s Building, now the subject of one of the Pacific Standard Time exhibitions, “Doin’ It in Public: Feminism and Art at the Woman’s Building. It was the most radical and complete experiment in a self-run politically directed education, really admirable.

As a faculty member in an MFA program, I’m torn, my students come in recent years not because they think they are going to make it, for the most part, but because they want to be in a central place where they can be exposed to new and challenging ideas (ideas that challenge their previous beliefs). Even though I feel increasingly confined by the situation, and miss terribly the atmosphere of creativity and freedom of the school I went to at the time I went to it, most of them feel that they get something for their education (though some, those who did drink the Kool Aid) also later feel terribly embittered by disappointment) and when I try to imagine alternatives to the MFA, as I discussed at Cabinet last year, you can see how rapidly necessities of institutionalization reconstruct themselves (after the first flush of experimentation, you need a space, you need money for rent, you need insurance, people need to be paid for their labor in teaching or maintaining etc…)..that’s why The Women’s Building was such an inspiring model.

Kate Kretz: Haven’t really thought about this. I am much more concerned/dismayed at the corporatization of higher education… I think that it’s going to transform this country, and makes me want to bail out to live in a place where education is the priority.

Oriane Stender: I would love to bail out. Anyone in Sweden want a middle-aged mail order bride??

Rocio Rodriguez: this whole thing is well intended but frankly…it waters down the real message…which in my view should start in occupying the capitol both houses of Congress. Once you start down this occupying street hell u can justify occupying anything. I say focus on what and who has created the problems and put us in the present economic situation. Start w/our ‘elected’ officials and demand an accounting there. A lot of $$$ passes through those halls, campaign contributions, lobbyists…they spend more time raising money for their next election than working on the country’s problems.

Goran Tomcic: Let me go back to my past and look at the former socialist countries education. It was required, grand and open (yes, it was open and they way to escape the system), and yet by the end of the 80’s there was nobody left who wanted to live in socialism and receive free education or free medical care. Now you go back to those former socialist countries and the first thing you notice is the luck of an education, nobody is reading the Classics any longer, and now we are just like the rest of the West.

Mira Schor: Rocio, I hope there are enough people to go around to focus on the multiple aspects of the culture and work in specific areas where they can have an impact, however momentary. In that sense I think it is worth doing, because the financial system needs critique, the corruption of the electoral process by money needs protest, and the art world and education are areas of culture that many of us here occupy. It’s a long term process and many contradictions. Revolutionary movements sometimes don’t have the time for contradiction until it takes them over, alas.

Ree Dykeulous: See W.A.G.E. |working artists and the greater economy. Fully budgeted/hugely endowed NY museums exploit cultural workers- aka their content providers

Rocio Rodriguez: Yes I agree with what you have said Mira the multiple aspects…they are all connected. I suppose that one only has so much time/resources to devote to protest and I see Washington as a central player to all of this and for me areas of culture are secondary (and I am an artist-who is totally dedicated to my profession) to the very present needs of many people who don’t have jobs, can’t pay for health insurance, and are worried about keeping their house. In any case its a mess all around. thx for the discussion.

Betty Tompkins: one of the huge differences in art/art education is that when I was a student we were told flat out that we should not come to NYC with the expectation of making it big or even making it small very quickly. we were told that it takes time to mature as an artist and that you did this on your own, outside of the gallery system. Today’s grads think an mfa is the same as an mba. It is not.

Mira Schor: here are some views on Hyperallergic to add to the mix. “Is Occupying Museums Misguided?” “A protest is slated for tomorrow that intends to “occupy” the Frick Museum, MoMA and the New Museum, but why?”

William Evertson: My only observation is that museums seem to be a symptom and wall street excess is a cause. I can certainly relate to the desire to expose the corporate hand that is driving these cultural icons. I wonder what the alternatives look like? With people in such need throughout the country how many would support any cultural activity?

Mira Schor: re. the Hyperallergic piece, just to play devil’s advocate for a minute , while I am wondering about this occupy museums plan, isn’t asking “what a museum of the 99% would look like and who/what would fund it” as Hrag Vartanian does on Hyperallergic the same as saying that occupy wall street hasn’t articulated specific demands>>>they have gotten people talking and put somethings on a wider agenda, so perhaps this can’t hurt either even if it seems a bit elitist in relation to the 99% meme

Sean Capone: Just do it, what do you have to lose! Keep in mind a lot of people won’t care about this action and it underscores the derisive notion that OWS is a bunch of liberal arts majors with worthless degrees. If art is for the people then go make art for the people. Or if this makes you feel better about yourself–do this. The museums aren’t the ones keeping arts funding out of the ‘people’s’ hands–you should go OccupyTheNEA. By the way, the New Museum had their Ostalgia ‘peoples art’ show all summer and the people didn’t go see it. The people want graffiti art and Tim Burton shows. Was burning a flag of dollar bills at the OWS art show a good example of art for the people? (did that really happen?!) As one of the 99% I would have rather put it in the donation box.

Betty Tompkins: ♥ hrag.

Ree Dykeulous: Debating whether the culture industry and all of it’s tethered institutions are unethical and participatory in an exploitative inhumane financial scheme is nonsensical- it is. The pay scale and disparities in non-profit institutions (directors and board members alike) directly reflect the inequity in other industries so it’s time to ask the museums why, esp. since, (1) they don’t distribute payment to artists but rather act as representatives of commercial galleries & auction houses, (2) act as representatives of the industries from which their monies derive. See Major Earners in the Cultural World for details. Museums absolutely DO keep payments out of artist’s hands b/c no oversight is required regarding the distribution of institutional funding by public-private partnerships (whether the monies come from granting organizations, foundations or private monies). So being as the system is at this present moment, it’s inequitable, unethical and unjust in it’s relationship with the visual artists, performers, arts writers and independent curators with whom they choose to work, and from whom they are gaming with cultural capital known as “exposure”.

Grace Graupe Pillard: I remember when I first studied art – never having gone to Art School – and discovered the wonders of art – the length and breadth of its history at MOMA and the Met and the Frick…I went there for free almost every week or more to study and discover artistis and how to paint, and how not to paint, and what I considered good and bad painting. One helped me see the other.

This can no longer be done – Now we pay – and we pay – particularly at the Guggenheim, New Museum and MOMA – yes we lucky artists can get an Artist Pass at MOMA but the Guggenheim does not even deign to allow that. I am ambivalent and really do not know why – something inside of me feels uneasy with occupying Museums. Old habits die hard. So this discussion is refreshing and making me consider and re-consider the issues.

Judith Rodenbeck: Fluxify museums; occupy the Supreme Court.

Nato Thompson: As far as I can tell, the idea of occupying everything makes sense to me. If people occupy the institutions for which they are direct constituents (artists occupying museums for example) that certainly makes a lot of sense. I think people are feeling too defensive for museums. I used to work at one and we would have embraced a conversation around audience and funding. They are public institutions accountable to a public. It would be good to have the 99 at their door. It’s like feeling defensive for a government because the people show up to vote. That is the point. If anything, I think of this is a reminder of a mission statement. Of course artists like art, they are artists. So of course they have some sympathies for museums as an idea. I don’t think this needs to be thought of as a protest so much as an opportunity to consider who art is for, how it is funded and how is it accountable. It is the same question of wall street, governance, etc. Who can disagree with these basic questions? Funny that hyperallergenic article dismisses the idea and then goes on to pontificate on why not start a museum that supports the 99 (the article asks)? Well, isn’t that what the missions statement of all non-profit museums are? And finally, art is a place where these ideas should be embraced and shared. It is about free expression and our institutions are there to embrace that. That is their role. We should think of them as an infrastructure accountable to the public and use them as such. To dismiss using them seems almost as though we have given up on them.

Betty Tompkins: I actually have the record of The Investigator, the original and i had a cd made of it as it is really rare. The actual story is quite close to what my parents told me when I was a kid…I grew up with this record.

Rocio Rodriguez: I am not sure that I fully understand Nato Thompson’s comment above. “(museums).. ‘They are public institutions accountable to a public.” Accountable? What exactly that you want them to be accountable for? Who is giving them money? Remember Jesse Helms? He wanted to make institutions that received public money accountable for the art that they showed. The following excerpt is from a Huff post article —“According to a 2006 report issued by the American Association of Museums, since roughly the late 80s museums have registered a 15% drop in reliance on public funding. Over the same period, museums almost doubled the amount of private funding they receive, counted as a percentage of their operating income. In recent years, half of American museums have shown growth in their endowments, while museums running deficits have decreased by one third. Business is private, and business is good (notwithstanding the real perils involved when museums get too cozy with corporate interests).” This was published in ’08. Maybe private contributions have dropped since the economic downturn. But I get a little concerned when I hear the word ‘accountable’ applied to ART or art institutions. It brings up the culture wars of the early 80s. Bottom line here is that museums are non-profits and they have to get money from somewhere–via government or corporate, private donors. Frankly, I happily hand over my 25$ when I visit the Met. It’s the Art, I care about and that is what I am supporting.

Betty Tompkins: excellent point Rocio.

Rocio Rodriguez: correction: I meant to say the culture wars of the late not early 80’s….one more thing…that quote from the huff post article was in direct relation to Jesse Helms effect on govt. funding.

Betty Tompkins: it was a disaster.

Rocio Rodriguez: we still feel the effects of it today.

Mira Schor: Rocio: when I was a teenager I stopped at the Met often on my way home from school. It was free. I could go in there to get lost, on purpose, and see what I would see, I could go to look at one painting. If it had cost the equivalent of $25 I would had gone much less frequently. Luckily the Met has a pay as you wish category, though most tourists don’t notice. But that is very expensive and contributes to the notion that art is only for an elite.

Rocio Rodriguez: Mira, I hear what you are saying. Yes it’s expensive even for me…but I guess I’m a sucker for art and I feel that it is my responsibility to support it.

Ravenna Taylor: what a great discussion. I love museums, almost any one of them is like a house of worship to me. I agree with so much of what each of you has said here; in particular I like the way Steven Nelson put this: “Museums are intertwined with money and our current corporate mess, but it’s not museums that got us into the economic and social mess we face today.”

I posted this same link this morning, and acknowledged having my own doubts about some of the content and the language.

But I really am terribly excited to see questions posed, with expectations of answers, and large numbers, young and old, contemplating meaningful change in the ways that our society functions, at all sorts of levels. This is truly hopeful, for me. I may not agree with everything that might happen or be proposed, but I’m just glad to celebrate an end to complacency and fear.

Rocio Rodriguez: Last time I was at the Met, I asked the guy who was selling tickets, how many people pay 25$ ?(because I was curious and the two tourists in front of me opted for a smaller donation which is fine) and he said…actually quite a few. I was surprised and glad.

Oriane Stender: The general dissatisfaction/anger at OWS makes sense. The financial industry, taxes, investments, loans – that whole world is very confusing and many people (including me) feel lost in it. But that same vague distrust and anger doesn’t make as much sense when directed at museums. Being angry at high admission fees AND at corporate sponsorship doesn’t make for a focused argument. Corporate sponsorship reduces the admission fees the general public pays. NEA funds and other government funds used to finance museums to a larger degree. Now corporations and private money has to fill that gap. If we just show up to Occupy Museums and protest “the system” we will look like simpletons.

Ravenna Taylor: for some reason I am resentful when I pay admission to the Guggenheim, and I only go there if there is an exhibit I know I want very much to see. But I don’t feel the same way about MoMA or the Met, and I have memberships there so I can walk in as often as I want…My own argument has long been: less taxes to support war action; more taxes to support culture. Then we could have government support for cultural institutions instead of war industrialists, and not have to hear the Toll Bros plugged while listening to Met Opera Broadcasts.

Ravenna Taylor: My own argument has long been: less taxes to support war action; more taxes to support culture. Then we could have gov’t support for cultural institutions instead of war industrialists, and not have to hear the Toll Bros plugged while listening to Met Opera Broadcasts.

Cole Robertson: Not sure if this came up in the 70+ preceding comments, but here’s my take: corporate support of the arts is almost invariably a corrupt enterprise. It either serves to boost the market value of the corporation’s art collection, is a PR stunt to rehabilitate a tarnished image, or is a tax dodge. Either way, nasty.

Oriane Stender: Cole, other than a soup kitchen, what would be a non-corrupt enterprise? Pretty much everybody expects to get paid for doing what they do.

Ravenna Taylor: Money is never clean. The super-rich corporations like Toll Bros or Koch Ind. could, if philanthropy were their object, make their donations and not demand they be acknowledged multiple times in multiple ways. It’s not the way the world works of course; but as an idealist I feel I must point out, it is one of the options, to donate without the need to use the donation as advertising. Considering that they are surely writing the donation off if they are paying any taxes at all, using it to promote their businesses and their images is something that shouldn’t even be permissible. Just the opinion of a crazy idealist.

Cole Robertson: For starters, eliminate tax breaks for increasing the value of private collections. You wanna advertise the art you own to make it more valuable, Charles Saatchi-style? Fine. Just don’t do it with taxpayer money…Ravenna, exactly. We’re underwriting their PR budgets, and it’s flat-out wrong.

[…]

Kathy Schnapper: Slightly off-topic: OccupyMuseums is reawakening all of the ambivalence within me about issues of class and the practice of Art History. Remember the first time that I read Sir Kenneth Clark’s autobiography. He wrote about his early exposure to the finer things in life and how it was essential to his development in connoisseurship. My background was blue collar, and that idea continued to haunt me and make me feel inadequate.

Recall when PASTA first organized the MOMA staff. My family were early union organizers, but somehow I felt uncomfortable with the idea of museum workers in the same union with mere laborers (of course, I grew up quickly from that absurd position).

And then there was graduate school at Columbia: At the time I had a day job working with abused and neglected kids. James Beck told me that I could not be a serious art historian and continue to do that. So for years, I never mentioned it.

Bringing all of this up, because the legacy of these experiences continues to tug at my emotions and colors some of my rational response to #OccupyMuseums Glad that they have opened up this important area of discussion.

***

I appreciate this conversation, it’s been useful to me and I hope to anyone catching up on my blog. I thank everyone who participated, and since I suspect the conversation will continue, I will update it if necessary. so, more later. Any comments to this blog post should if possible be directed to the conversation on my Facebook page so I can pick them up from there. A similar conversation on this subject took place on Stephen Nelson’s Facebook page.

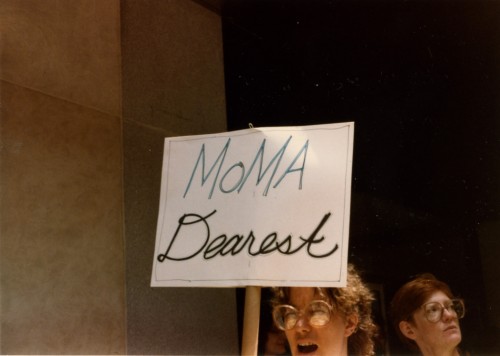

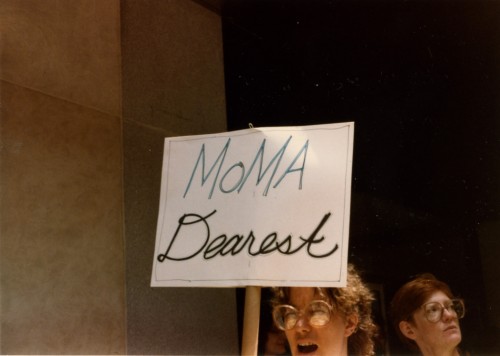

And for fun, here are some pictures I found of a demonstration held in front of MoMA June 14, 1984, when the museum reopened after a major renovation with an exhibition which included almost no women artists.

Lucy Lippard and May Stevens, demonstration in front of MoMA, June 14, 1984, photo: Mira Schor

Rob Storr, Nancy Bowen, & Barbara Siegel, demonstration in front of MoMA, June 14, 1984 (Rob became Curator in the Department of Painting and Sculpture at MoMA in 1990 (to 2002).

Demonstration in front of MoMA, June 14, 1984

Plus ca change, plus c’est la même chose: in recent years MoMA has had special funding from Sarah Peters to focus on their collection of works by women artists, designers, and architects, has hosted a number of symposia on the subject of feminism and art (I’ve commented on these on this blog and, along with other women artists, on M/E/A/N/I/N/G Online), and major women artists have had exhibitions and installations in the Atrium, and yet the majority of retrospectives, of works exhibited, and of women included in themed group exhibitions has by far remained skewed towards work by male artists… this is only to say that change is slow and hard at any major institution, and museums are perhaps even more impervious to change than governments! It is an ongoing battle of which Occupy Museums will be a new stage.