This post contains video clips that may not play in some email programs.

It is a fun and utterly cosmopolitan thing to do to go see a movie alone the first day it comes out on a cool grey late spring day in mid-week, at mid-afternoon in New York City. It’s a Truffaut/Godard thing to do, by way of saying that yesterday, Wednesday, restlessly trying to feel the pulse of a return to work in the studio after a hard season of teaching and wrestling with the publication of my book and the launch of this blog, I took myself to the Film Forum to see Two in the Wave, Emmanuel Laurent’s new film about the artistic friendship of Jean-Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut.

In my teens and early twenties I was a Truffaut person. I remember seeing Breathless but it does not seem to have left the lasting impression on me that seeing Jules et Jim did (these films were released in 1960 and 62 but I probably didn’t see them until about 4 or 5 years later) — Jean Seberg versus Jeanne Moreau… I’m sorry. But I seem to recall that when I read about Godard’s other films, and I read the New York Times and New Yorker art and film criticism pages even more closely and with more of a sense of moment and thirst then than I do now, I felt somehow intimidated or, probably more so, the people and the language that supported Godard seemed intimidating to me. Maybe they were more radical and in the context of the late 60s I may have been more conservative than the vanguard of my generation — I loved Antonioni too, so there was some general sensibility there. The poeticism of Truffaut resonated deeply, as did the sense of longing. For instance, for me as a young girl, the scene in Jules et Jim when Jeanne Moreau puts cold cream on her face before going to bed with Jim in the doomed hope of conceiving a child, was a mysterious key-hole view into an adult sexuality.

Still from Jules et Jim

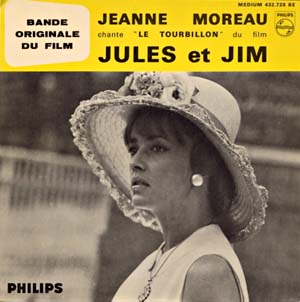

I had (I bet I still have somewhere) a 45 rpm record of Jeanne Moreau singing Le Tourbillion (Dans le Tourbillion de la Vie) which I listened to often:

Record cover art, Jeanne Moreau, Le Tourbillion, from Jules et Jim, 1962

The Wild Child is a film I think of often: Truffaut’s own reserved and gentle presence as actor and narrator, the story of the effort to educate a feral child, particularly the experiment to see if he understands the concept of justice, the beautiful use of black and white, the simplicity and seeming verisimilitude of the settings make me feel that I have spent two hours in post-Revolutionary France inside the mind of an Enlightenment figure.

Now I am also nuts about Godard movies. While having steered clear of Godard in my youth may have been a terrible and costly mistake — I might have understood modernism and radicality so much better and perhaps fared so much better professionally as a result had I followed Godard much earlier (pitiless irony does so much better) — it has also been a gift to discover the movies now because seen at a remove of 40 or more years they are on the one hand as filled with a very similar sense of charm and a kind of innocence to that of Truffaut, (see Masculin/Feminin and Stolen Kisses), as or more poetic (see Alphaville), and at the same time the sharp, disjointed, Brechtian editing style, bright color aesthetic, and the political satire as well as the uncanny apparition of Abu Ghraib-like imagery of films like La Chinoise are as brilliant and radical and new now than then, maybe more so. But as I embrace Godard I would hate to think of Truffaut as seeming lesser. Two poets can exist in the world, even if eventually they can’t speak to each other, they can both still speak to us.

I highly recommend seeing Two in the Wave. It is a complex, imperfect yet fascinating and also touching documentary on the friendship of Truffaut and Godard from the day they met in 1949 — a moment captured in as uncanny a photograph as that of the young Bill Clinton shaking the hand of President Kennedy. Was anyone there to shoot a picture the day Damon met Pythyas? — to the bitter end of their long and productive friendship in 1973.

The only flaw in the film is the organizing frame of a young woman, “played” by actress Isild Le Besco in order to humanize the director’s focus on reams of archival print material. It’s kind of a waste of time but doesn’t harm the film which offers so much rich material. The film is “about” a number of things: the history of the Nouvelle Vague as a radical movement of rupture from tired rules of commercial cinema is laid out though the interpolation of archival copies of the Cahiers du Cinema to which both men wrote film criticism before they started directing their own movies, a radical rupture paradoxically rooted in their passionate and redemptive love for the history of film. The importance of influence, homage, and quotation is a major theme with many scenes of each man avowing his admiration for the same directors: Jean Renoir, Fritz Lang, Alfred Hitchcock, Roberto Rossellini are cited as major influences by both. There is a fascinating clip of an interview between Fritz Lang and Godard, with Lang urbanely speaking in flawless French, as well as appearing as himself as film director in Godard’s Contempt. The whole mid-century phenomenon of “cinephilia” is discussed at length, a passion that I’m not sure is as prevalent now: how many times do I tell some student working in video about basic film form: editing, lighting, script, and mention someone like HItchcock and meet a blank stare.

There is an interesting section on the influence of Bergman on both of them, in particular how he taught them to film women, not just their bodies but their subjectivities, their desires.

Each film reference is a line of a must see filmography.

This is also a tale of two ambitions and of the moment when politics was the excuse for an irreparable break. They had often worked in tandem in support of film and other causes. Both were involved in the February-March 1968 demonstrations in Paris to protest the firing by Andre Malraux of Henri Langlois, co-founder of the Cinemateque Francaise and one of the many father figures they shared a passionate admiration for.

Although for many years they often engaged in political activism together up to and including the events of May 1968,the two men eventually split over politics. Their films went in different directions. Truffaut died at the early age of 52. Godard still works although some of his recent work including Histoire(s) du Cinema is often quite hard to access particularly here in the United States and he has kept himself remote. Still the tenor of their final exchange of letters indicates long simmering resentments. After the release of Truffaut’s 1973 film Day for Night, Godard wrote him, denouncing his (a)political declarations about the nature of film and calling him a “liar.” Truffaut responded in a 20 page letter, calling him a disingenuous shit who always managed to make himself out as the victim and denouncing Godard’s politics as fundamentally hypocritical and inauthentic, “That men are equal is a theory for you.”

But then the film ends on another note, not exactly reconciliatory but nevertheless of a different tenor, like, very like, reviewing the life of a child after having told the story of his parents’ happy marriage, differing natures, and bitter divorce: the very close artistic and personal relationship that both directors had with the actor Jean-Pierre Leaud, who was effectively, as the character Antoine Doinel, the alter ego of Truffaut in The 400 Blows, Stolen Kisses, Bed & Board, Love on the Run, in addition to his appearances in other Truffaut movies as well as the star of major films by Godard including Masculin,Feminin, La Chinoise, Love on the Run, Made in USA, and Weekend.

Two in the Wave ends with Leaud’s first film test interview for The 400 Blows. Then about twelve years old, he is cheeky, eager, Parisian: “are you sad or happy?” asks the off-sceen voice of Truffaut. “Je suis pas triste, je suis gai,” I’m not sad, I’m happy,” answers Leaud, replicating without knowing it one of the most exquisitely poignant moments in the history of French film, when in Les Enfants du Paradis (Children of Paradise), the character of the heroine, the beautiful Garance, played by Arletty, says in a bright and brittle tone, with a beautiful smile masking a guarded heart, “Moi? Je suis gai comme un pinson.” “I’m as gay as a songbird.”

It is not altogether unfitting to recommend books of writings by, interviews with, and biographies of these two filmmakers because they began as film critics using writing to prepare a critical field for their work and their formations as critics and scenarists made them extremely articulate proponents of their ideas and of the history of film, in text and in interviews.

Interview with director Emmanuel Laurent about his use of actress Isild Le Besco as a silent framing device

Everything is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard by Richard Brody,

Books by or about Francois Truffaut:

Cahiers du Cinema: The 1950s: Neo-Realism, Hollywood, New

Wave, vol.1

However their films are the necessary element: these two men who spent their youths at the Paris Cinemateque studying the entire history of film should be honored by festivals of their films, and since this documentary focuses on their friendship it would be interesting to embody the productive interaction by scheduling/studying their films in dual sequential order: the documentary focuses on their actual collaborations, including Breathless, for which Truffaut wrote the screenplay, giving his already more developed stature to Godard in order to give him a chance to make his first full length film. But other alternating presentations would be fascinating: the double chronology of Jean-Pierre Leaud’s presence in both directors’ films for 15 years is one of the most interesting tri-lateral collaborations in the history of cinema, and one of the most charming to watch, and tragic to think about. I left the Film Forum envisioning a month-long, four screen festival, with Truffaut’s films running in sequence in the first, Godard’s running in sequence in the next (the Film Forum did have a great festival of Godard films in 2008 and one of Truffaut in 1999), then the dual presentation, film for film, running in the second theater; while in the third, and in the fourth, the directors they loved.. oh and no we need a fifth theater in which to screen all the other wonderful films of their time, by Eric Rohmer, Agnes Varda, Claude Chabrol, Jacques Rivette: in the documentary there are particularly affecting scenes from Jacques Demy‘s 1961 film Lola, and an adorable moment in one of the most beautiful movies of the era, Agnes Varda’s Cleo from 5 to 7, (1962) in which a short comic slapstick silent film staring Godard and Anna Karina reenacting how they met (cute) creates a moment of comic relief within as beautiful a reflection on mortality as any that exists on film.