Usually at some point greatness disappoints. Even very great artists sometimes falter, lose their way, run out of steam. Not so Louise Bourgeois, who transmuted a family story of paternal infidelity into a narrative of mythological dimension that she always insisted was the primary driving force of her work, and for whom that self-mythologized personal narrative served as an undying battery to produce great art works until the end of her very long life, her late stuffed cloth figural sculptures as raw, uncompromising, and young as her early objects and drawings.

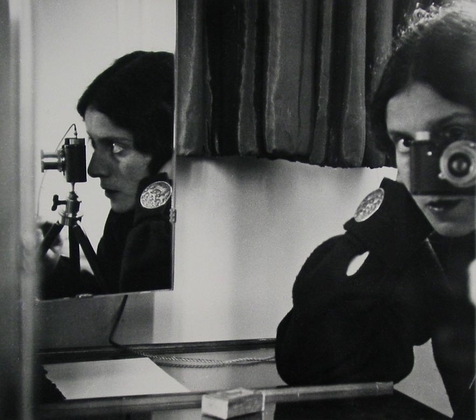

Louise Bourgeois, 1946

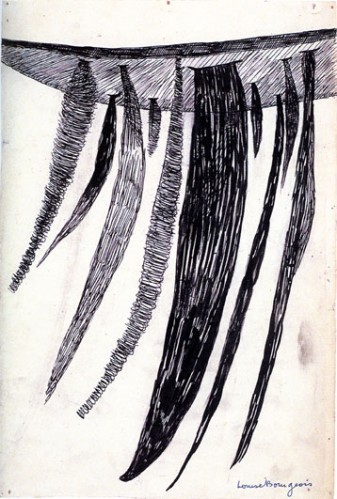

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 1950, ink on paper, 11"x7 1/2"

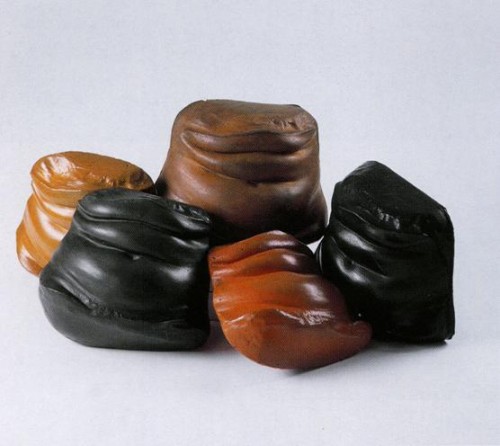

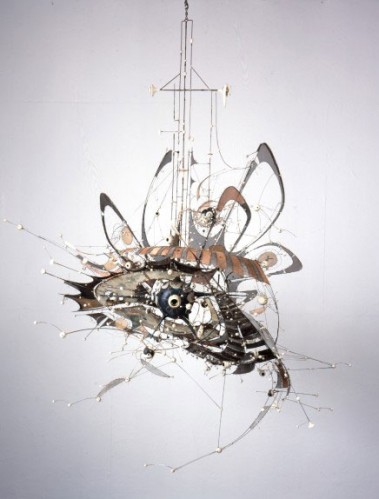

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled, 2001, Fabric and aluminum, 14 1/2"x11 3/4"x11 3/4"

***

“My name is Louise Josephine Bourgeois. I was born 24 December 1911, in Paris. All my work in the past fifty years, all my subjects, have found their inspiration in my childhood.

My childhood has never lost its magic, it has never lost its mystery, and it has never lost its drama.” (Louise Bourgeois, epigraph, Louise Bourgeois: Destruction of the Father / Reconstruction of the Father; Writings and Interviews 1923-1997)

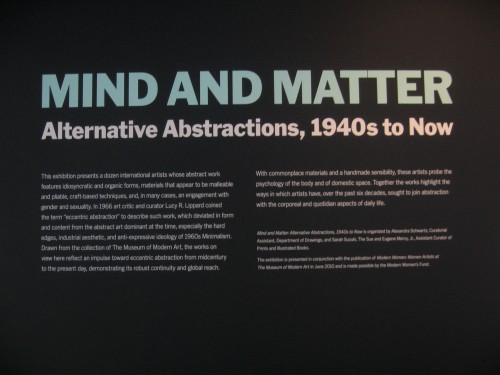

I first learned of her work from “Louise Bourgeois: From the Inside Out,” an essay by Lucy Lippard in her 1976 collection of essays on women artists, From the Center: Feminist Essays on Women’s Art. At the time, Lippard’s essay was first published in Artforum in 1975, Bourgeois was 64 years old. She died this morning, May 31, 2010 at age 98 (b. December 24, 1911-d. May 31, 2010) having created another lifetime’s worth of great art since Lippard’s critical appreciation.

Lippard began by situating Bourgeois work within the personal framework of the artist’s “psyche,” as did Bourgeois herself in all her writings about her work.

“It is difficult to find a framework vivid enough to incorporate Louise Bourgeois’ sculpture. Attempts to bring a coolly evolutionary or art-historical order to her work, or to see it in the context of one art group of another, have proved more or less irrelevant. Any approach–non-objective, figurative, sexually explicit, awkward, or chaotic; and material — perishable latex and plaster, traditional marble and bronze, wood, cement, paint, wax, resin — can serve to define her own needs and emotions. Rarely has an abstract art been so directly and honestly informed by its maker’s psyche.” […]

“It would, however, be a mistake to see Bourgeois as the classically “feminine” artist, adrift in memory and intuition, for her first formal “revelation,” and the origin of her love for sculpture, was solid geometry. Although, from the age of fifteen she worked with her parents as a draftswoman restoring ancient tapestries, she majored in mathematics at school, took her baccalaureate in philosophy, and studied calculus and solid geometry at the Sorbonne. Only in 1936, at the age of twenty-five, did she begin to study art history and art, with Léger, among others.”

[May I interrupt myself here to say that thinking about the mathematical and philosophical knowledge and the practical artisanal experience that Bourgeois brought to her art studies at age twenty-five helps to put the works exhibited in “Greater New York” at P.S.1 — by artists mostly under the age of 40, many much younger than that — into some perspective]

Louise Bourgeois, Femme Couteau, 1969/70, from Lucy Lippard, From the Center

Lippard’s discussion of Bourgeois’ sculpture Femme Couteau (1969/70) was particularly determinative and prescient, anticipating by a few years the more comprehensive focus on Lacanian terminology of woman as “lack” which dominated feminist discourse on representation in the 1980s and early 90s. Lippard quotes Bourgeois on this sculpture:

[Femme Couteau] embodies the polarity of woman, the destructive and the seductive. … The woman turns into a blade. … A girl can be terrified of the world. She feels vulnerable because she can be wounded by the penis. So she tries to take on the weapon of the aggressor. But when woman becomes aggressive, she becomes terribly afraid. If you are inhibited by needles, stakes, and knives, you are very handicapped to be a self-perceptive creature. These women are eternally reaching for a way of becoming women. Their anxiety comes from their doubt of being ever able to become receptive. The battle is fought at the terror level which precedes anything sexual.”

Lippard concludes:

“Bourgeois exists in the dangerous near-chaotic climate of Surrealism’s “reconciliations of two distant realities.” … Within the art (as, one suspects, within the artist) form and the formless are locked in constant combat. The outcome is an unusually exposed demonstration of the intimate bond between art and its maker. Despite her apparent fragility, Bourgeois is an artist, and a woman artist, who has survived almost forty years of discrimination, struggle, intermittent success and neglect in New York’s gladiatorial art arenas. The tensions which make her work unique are forged between just those poles of tenacity and vulnerability.”

Lippard’s essay marks the informed admiration which began to accrue to Bourgeois in the late 70s and early 80s. After decades of a kind of semi-neglect despite living within the elite of the center of the New York art world, Bourgeois was embraced by women artists for her immense contribution to the lexicon of representation of gender and gendered representation while at the same time receiving broad international recognition as a great artist in such a way that her success went well beyond a succès d’estime among women. What she did with the attention and the financial rewards it brought is truly astounding and inspiring, particularly given her age when she achieved material success. Bourgeois grabbed the opportunity to do larger pieces, taking on master media of sculpture — marble and bronze — as well as creating room-sized installations she called “cells.” Thus she was able to get beyond financial limitations on her production that she noted in one answer to a 1970 questionnaire: Q: “To what extent have financial considerations affected your work?” A: “Limited returns from my work have constricted my willingness to make the investment necessary for full production.” (from Destruction of the Father / Reconstruction of the Father).

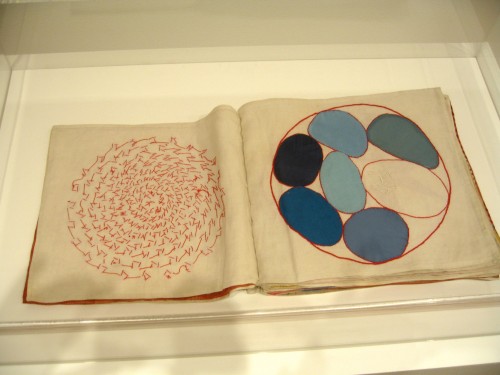

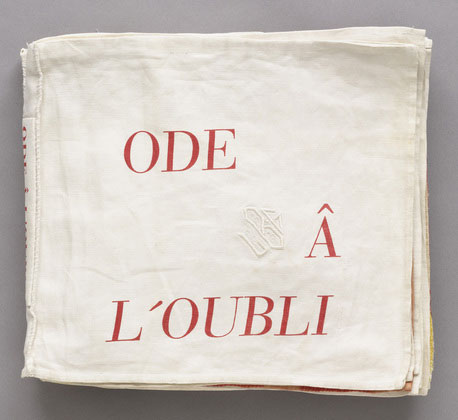

In recent years Bourgeois returned to the medium of textile where her art formation had begun as the daughter of tapestry restorers, making increasingly crude (that is direct) stuffed cloth sculptures that continued to transmit sexual power transmuted into sculptural form. Her figuration in these pieces was both raw and stylized yet did not seem mannered. Sometimes an artwork hedges its bets, or, by some minute concession to accessibility, in some tiny betrayal of form, apologizes for itself. I never detected that in Bourgeois’s work.

Louise Bourgeois, Couple IV, 1997, mixed media in vitrine,

Her work sprang out among the fray at Biennials and art fairs in recent years and, even if she had help in doing her work for many years, all her work showed the mark of her hand. I never felt the distance of factory production. One of my favorite moments in a film about an artist is one that was shown at her Brooklyn Museum retrospective, in which Bourgeois says something like, “you know we sculptors, we have to do this,” demonstrating what she means by “this” by, with a quick strong twist of her hands, bending a piece of rebar as she speaks, in her late 70s or early 80s!

I wish I could find that film clip but in this later video you get a little idea as you see her talking about using power tools:

In “From Liberation to Lack,” an essay I first published in Heresies 24: 12 Years 6, 1989, I wrote a little about some of Bourgeois’s work, influenced by Lippard’s earlier analysis:

“Louise Bourgeois also claims no distance from physical experience and autobiography. Her insistence that the source of her work resides in the psychological wounds inflicted on her by her father contravenes any formal theories of art and yet embodies the Oedipal crisis that psycholinguistic theory interprets as the entrance of human beings into the symbolic order of the Father. Bourgeois obsessively returns the critical audience of her work to its motivating source — the murderous rage of a betrayed daughter. Her admission to the symbolic order has been warped by her father’s open affair with her governess, yet her link back to the imaginary (completeness of relation to the Mother) is damaged by her mother’s presumed complicity.

The forms that Bourgeois’s anger takes are directly related to those of surrealism. The influence of “primitive” sculptures and totems is pervasive. “Primitive” art was a locus of the (female) unconscious of “civilized” (nonprimitive) Western man; its influence on a woman artist is bound to differ. Bourgeois’s Femme/Couteau and Giacometti’s Spoon Woman are kin but they are not sisters. Spoon woman has a tiny head and a large receptive body. Femme/Couteau, in its degree of abstraction, is ambivalent and bisexual. It is a vulva and a knife — what woman is and is feared to be. Bourgeois’s forms are blatantly vaginal, mammary, and womblike, yet exuberantly, mischievously phallic. It would betray her intent to deny the role of her own body experience. The rawness of her surfaces and the openly sexual nature of her forms vitalize the organic/biomorphic surrealist vision of lack and dissolve the distance the male viewer seeks to place between himself and the art object and between consciousness and his own suppressed physicality and mortality.” (from Schor, “From Liberation to Lack,” Wet)

In “Representation of the Penis” I wrote briefly of Bourgeois’s sculpture, Fillette, which she cradles in the noted and notorious 1982 photographic portrait of her by Robert Mapplethorpe: “This penis is everything: as Fillette/little girl it is the baby as penis substitute, as rugged depiction of a stiff penis and big balls it is a sexual instrument of pleasure … and as creator of this polysexual object, which she cradles in her arms, Bourgeois is indeed the all-powerful phallic mother.” (Wet, 34)

Portrait of Louise Bourgeois with Fillette, 1968, by Robert Mapplethorpe, 1982

In her MacDowell Medal Acceptance Speech in 1990 Bourgeois described how she came to have her photo taken with this sculpture in hand:

“The story of this photograph is actually quite complicated. When Mapplethorpe approached us to make this portrait, I was a little apprehensive….Instead of being photographed candidly in my own studio, I had to go to Mapplethorpe’s studio. That is how it is with highly-professional photographers …they work on their own terms and operate from their own studio. It was up to us to go there. That gives me stress.

So I prepared with Jerry Gorovoy and appeared as scheduled at Mapplethorpe’s studio. This is my attitude towards men, you have to be prepared and work at it…. You have to prepare everything. You have to feed them, tell them they are great, you literally have to take care of them. …I mean, it’s really a job.

So the day of this appointment at Robert’s studio, I thought, ‘What can we bring? What prop can we bring?’…So I got Fillette (1968), which is a sculpture of mine, which was hanging among others. I knew I would get comfort from holding and rocking the piece. Actually my work is more me than my physical presence. So the sculpture is in the background of the photograph.

You see the triple image of the man you have to take care of, of the child you have to take care of, and of the photographer you have to take care of.”

Even if Bourgeois, like many women artists, did not necessarily like to be pinned down to being (only) a woman artist, her critical view of patriarchal power and its warping effect on relations among women, is one of the foundations of her work.

Louise Bourgeois, Nature Study, Velvet Eyes, 1984, marble and steel, 26"x33'x27"

One of my favorite works by Bourgeois from the 1980s was Nature, Velvet Eyes (1984) made at a time when, along with “lack,” the gaze was such an important term of feminist theoretical discourse — lack and the gaze, a psychoanalytic landscape of gendered representation, in which, according to Luce Irigaray’s analysis of Freud and Lacan’s theories, “Now the little girl, the woman, supposedly has nothing you can see. She exposes, exhibits the possibility of a nothing to see.” (Irigaray, Speculum of the Other Woman, 47). “Here the object of the gaze, a tub of stone, has eyes which stare back up at the viewer. The specularized “nothing to see” ogles back unblinkingly, recuperating the agency of vision.” (from my 1994 essay, “Backlash and Appropriation,” in The Power of Feminist Art).

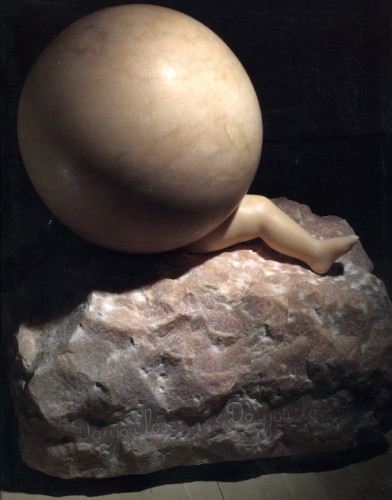

Louise Bourgeois, Untitled (with Foot), 1989, marble, 30"x26"x21"

In what conceptually seemed like companion pieces to Nature Study,Velvet Eyes, Bourgeois inscribed text into the bases of exquisitely carved pink marble sculptures of truncated body parts: “Do you love me? Do you love me” insistently asks one such sculpture, of a baby’s foot emerging from a large and perfect spherical egg or zygote. “Yes, I love you” answers another.

From what I gather from people who knew her, Louise Bourgeois was not necessarily always an easy person — why should she be? how could she be? I only mention that because it is essential not to sugarcoat an image of a cute little old lady artist, she’d have bent you like that piece of rebar for suggesting such a thing. But she was uncannily and informatively direct in her writings and statements, vivid, sharp and unyielding as a speaker, and brilliant as an artist, in her treatment of her subject matter, in her lines, her forms, her surfaces, her approaches to materiality and space. I love her work.