This is a wood-engraving by my father Ilya Schor, one of a series of illustrations he made in 1953 for the publication of Sholom Aleichem’s Adventures of Mottel the cantor’s son.

Mottel and his family immigrate to America from Kasrilovska, their shtetl in Eastern Europe after Mottel’s father, the cantor, dies. The events take place at the turn of the 20th century. Sholom Aleichem began writing the book in 1902, when he still lived in Europe, and it was the last book he worked on before his death in New York City 1916. The last chapter is unfinished.

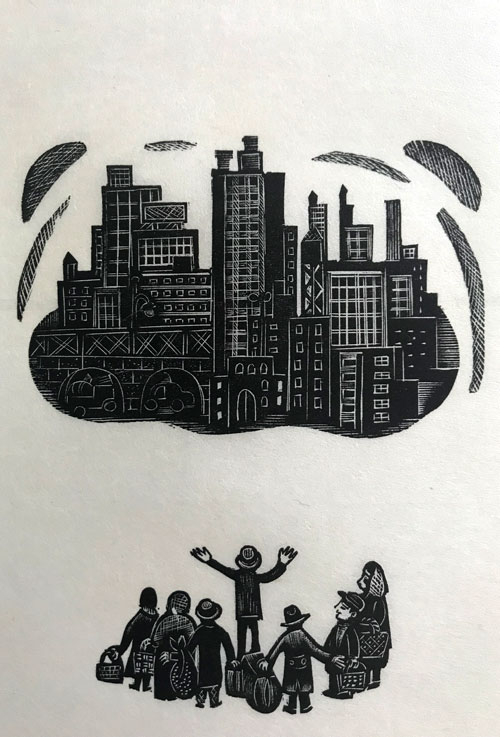

The plot may sound a bit gloomy, but actually it is a charming book, written in the mischievous and irrepressible voice of young Mottel. The first part of the book is entitled, “Mottel in Kasrilovska: Hoorah I’m an Orphan”–I first read the book some time after my father died and found the title very ironic. The second part is “Mottel in America: ‘Try not to love such a country.'”

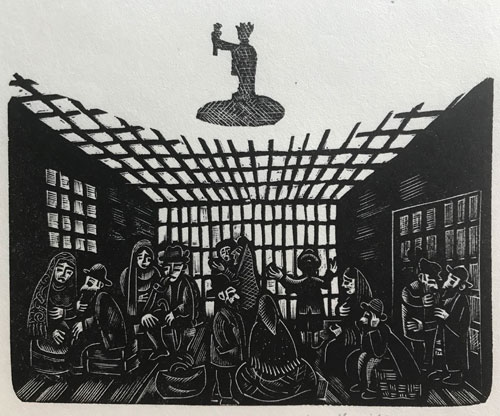

The image above illustrates one of the chapters on the family’s time on Ellis Island. This chapter is called “in prison.”

What are we doing on Ellie’s Island? We are waiting for our friends and relatives, and then we’ll be registered. As a matter of fact, we have already been registered over and over again. Our names have been written down, crossed out and rewritten *before* we boarded the ship, *while* we were on the ship, and *now* that we have disembarked from the ship. The same business every time. Who are we? Where are we going? Whom have we got in America? …

We had to pass over a long bridge with little doors on both sides. We had to walk in single file, one by one. At every step, we were halted and a different nuisance with bright buttons scrutinized, examined, prodded and pounded us. First of all they turned our eyelids inside out with a piece of white paper, in order to examine our eyes. Then they examined the rest of our limbs. And ever one made a chalk mark on us and pointed where to go next, right or left. Only after this was over were we permitted to enter that large hall and find one another. By the time we got there, we were bewildered, confused and frightened.

On top of the troubles and tribulations which we ourselves had suffered during our journey, on Ellis Island God has given us a glimpse into the troubles of others. If I were to tell you all the sad stories we have heard during our imprisonment on Ellis Island, I’d have to sit with you a whole day and a whole night, and talk without a stop. For example, there’s the story of a man, his wife and their four children who are detained on the Island. They can neither enter nor return. And why not? Because during the examination it has transpired that their twelve-year old daughter is unable to count backwards! When they asked her, how old are you, she replied, twelve. When they asked, how old were you last year, she didn’t know the answer. They told her to count from one to twelve. So she counted from one to twelve. They told her to count from twelve to one, but that she was unable to do. Now, if they asked *me* to do it, I’d let them have it proper. It’s no great trick… Well, it was decided that the little girl couldn’t be allowed to enter America. Here was a problem–what would happen to the parents and the rest of the children? A stone would melt at the sight of the parents’ distress and the agony of that miserable child.

As it has always been, immigration from a beloved home is caused by poverty, the hope of a better life, longing for the family who has gone before you, and by danger.

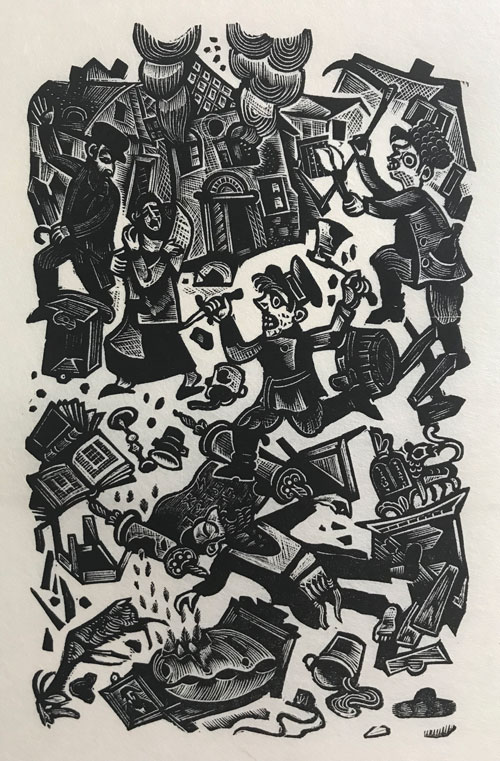

Mottel learns about pogroms from another boy he meets on the long trip across Europe to Antwerp, their port of departure.

All the emigrants keep talking about “pogroms” but I don’t know what they are. Koppel says, “Don’t you know what a pogrom is? Then you’re just a baby! A pogrom is something that you find everywhere nowadays. It starts out of nothing, and once it starts it lasts for three days.” “Is it like a fair?’ “A fair! Some fair! They break windows, they bust up furniture, rip pillows, feathers fly like snow…” “What for?” “What for? For fun! But pogroms aren’t made only on houses. They’re made on shops, too. They break them up throw all the wares out into the street, scatter them about, pour kerosene on them, set fire to them, and they burn…” “Really?” “Do you think I’m fooling you? then, when there’s nothing left to break, they from house to house with axes, irons and sticks, and the police walk after them. They sing, whistle and yell, ‘Hey fellows, let’s beat up the Jews!’ And they beat and kill and murder.” “Whom?” “What do you mean, *whom*? The Jews!” “What for?” “What a question! It’s a pogrom isn’t it?”

The reasons for emigration/immigration never change, only the individuals and the circumstances of specific historical moments. My parents’ immigration to the United States was tragically caused but at the same time and for the same reason exquisitely timed in terms of finding the perfect audience for my father’s artwork so that he could make his work and a unique name for himself: in the immediate post-war era American Jews just one or two generations removed from their immigrant parents and grandparents, who had fled oppression, poverty, and pogroms to find opportunity in the streets paved with gold of America, had indeed succeeded —among these were prosperous businessmen who were assimilated– to a point–their lives mirrored the white gentile American dream but they were still segregated by custom and quota to Jewish schools, suburbs, country clubs. They were devoted to community and synagogue while being major supporters of the arts.

After the war, this generation of Americans were deeply moved by the fate of the Jews in the Holocaust–they knew that, but for immigration, they would have been among the perished as were remaining distant members of their families. They were primed to welcome my father’s tender and also erudite representations of the life of the Eastern European Hasidim he’d been born into and that he held in his heart and soul long after he had left that world for a more cosmopolitan European culture. Representations of a past that the parents of my father’s American patrons had distanced themselves from in order to succeed in the new land were now desired and valued.

In that period my father illustrated books by Sholom Aleichem and by Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, all published around 1950. His illustrations for Mottel were done long before Fiddler on the Roof fixed certain clichés. They were based on his own life and collective memory, of both the rural pleasures of village life and of the deeply pious life of the Hasidim.

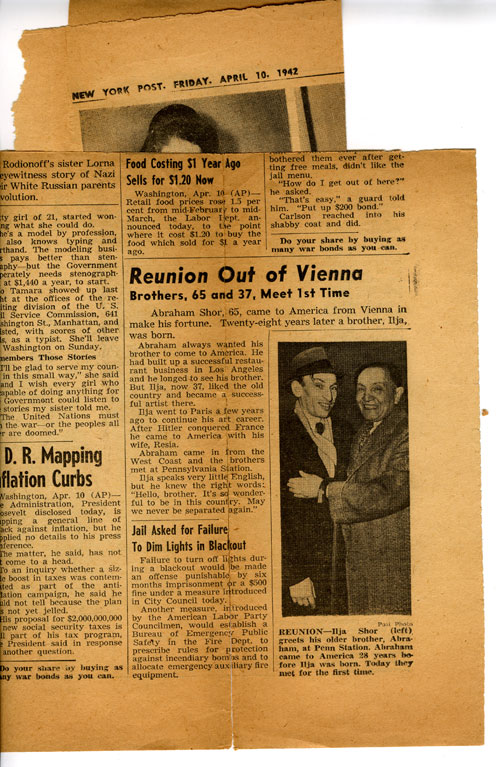

My parents did not arrive at Ellis Island. Their ship, the SS. Colonial from Lisbon, entered New York Harbor where immigration officers processed its passengers directly on board. It was December 3, 1941.

Israel Schor became a naturalized citizen of the United States as Israel Ilja Schor December 29, 1947. Over time his name changed informally to Ilya Schor because in America you could become what and who you wanted.

I think it is important to tell you that that my father cast his first vote as a US citizen in the 1948 election, for the Progressive candidate Henry Wallace. He voted for Adlai Stevenson twice. His first vote for a winning candidate was for John Fitzgerald Kennedy in 1960. It was a big deal.

Last week amid the furor over the punitive separation of immigrant children from their parents at the border with Mexico, it was announced that the current administration is also planning to go after naturalized citizens, looking for any small irregularities and infractions in order to strip such citizens with full rights as such of their citizenship and deport them. There have been politically motivated deportations but to my knowledge deportation of naturalized citizens has not been proposed as malicious policy not even during the McCarthy era or after 9/11, until now.

‘Try not to love such a country.’