Let me start by saying that I am not a huge fan of Robert Motherwell’s work although, or perhaps because, it is part of the visual landscape of what was considered good painting in my youth, with all the repressive elements that such a term might imply.

The Dead Motherwell spoke at the Pasadena Art Museum when I was a graduate student at CalArts and I remember him saying, in an effort to reach out to younger artists working in new media, that every generation of artists is faced with a wall and there is always a chink in the wall where one can break through, but the location of that chink, its nature changes, so that if for his generation the chink was located in painting, he understood, with what nevertheless seemed like some condescension, that perhaps at that moment (Spring 1973) the chink might be located elsewhere. I remember thinking, thanks a lot, you mean you had yours and now whatever, what about those of us who still are committed to some understanding of painting?

I have another relation to him that is irrelevant to art criticism but that places him in a fonder one degree of separation–when the upper echelons of the New York School artworld moved from summering in funky old Ptown to the Hamptons starting in the late 50s, he stayed on and was a mainstay of Provincetown’s art scene for decades: one used to see him tootling around town in his Rolls, or was it a Mercedes–a convertible for sure–and I’d stand behind him on line at the grocery store as he bought potato chips and if my memory serves me right Dorritos, or was it Cheetos?– in preparation for the weekly poker game he went to with a bunch of regulars, old pals and neighbors from the East End of town. His funeral service June 20, 1991 was held on his deck, at low tide, and was open to everyone. Apparently when he had his final heart attack and the local volunteer rescue squad came to take him to the hospital in Hyannis, he asked to look at the bay one more time, perhaps he knew it was one last time, or so it was told. I felt bonded to him in that love of a place and my morning summer walk on the beach if it is low tide takes me to his house (left as was for 22 years until it was sold this summer, probably tarted up next) and out onto the farthest flat that extends out in front of it.

This personal digression may seem to have nothing to do with anything of relevance to artworks currently on view in New York City but possibly it makes sense when considering that perhaps what is living and what is dead in art does not necessarily have much to do with the present condition of the artist. At the very least I can confirm by having attended his public funeral that the artist Robert Motherwell is really most sincerely dead. But the happenstance geographic sympathy I feel with him doesn’t change my views about those of his works that I find trapped in a formalist politesse that smothers the spirit of abstract painting.

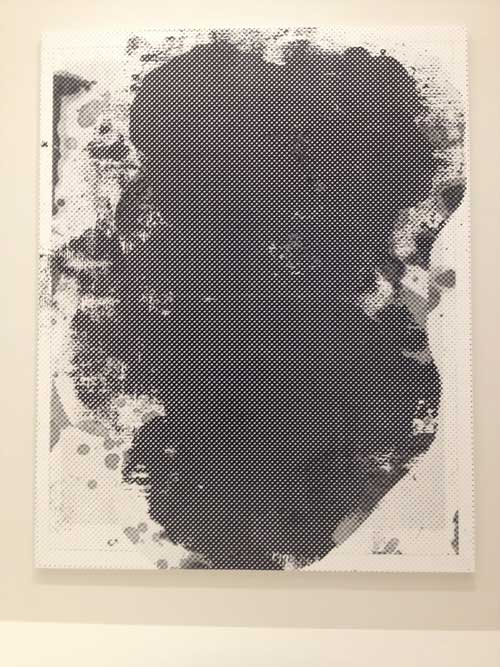

The Dead Nor am I a fan of Christopher Wool’s work, pacem the canon formation/hagiography in operation in many of the notable reviews of the show–Peter Schjeldahl: “Like it or not, Christopher Wool, now fifty-eight, is probably the most important American painter of his generation,” Roberta Smith: first, October 24, “this exhibition is an elegant experiential treat” but, while assuring him the best patrilineage, still a bit tepid “How a painting is made has long been part of its content — before Pollock for sure, and even before Manet. Mr. Wool contributes to that continuum” becomes, Friday December 27, 2013 (page C22 of the newspaper), “”one of the most beautiful exhibitions to unwind up the Guggenheim’s spiral ramp in some time” (FYI my post about Picasso Black and White last January 1, 2013), and pacem his anointment by the market. The works I am most familiar with, the black and white language paintings, leave me cold as conceptual word play even as I acknowledge that all his paintings are impeccably elegant in terms of postmodern formalist “im-politisse.”

So when a friend who was in New York for just a few days and was trying to see as much art and as many friends as possible in a short time suggested either the Chris Wool and Robert Motherwell exhibitions at the Guggenheim or Chris Burden at the New Museum, I chose the Guggenheim mostly because, of the two possibilities, it was the easier one for me to get to. But even when there is work you don’t feel you have to see, you never know when work you think you know will surprise you, and my museum visit turned out to be an example of that.

A firm believer in the assistance of gravity, when it comes to the Guggenheim, I always start at the top of the ramp and work my way down even though the museum persists in placing chronology in the reverse direction so that if you care about chronological order you have to climb up from the beginning of the artist’s career to the top. So as we passed by some of the corporate-lobby elegant swirls and swooshes of the large most recent works around the 6th and 5th floor levels, I started wondering at what point going backwards down into his past we would arrive at the work that was deemed just sufficiently interesting or edgy to be noted by people in the New York artworld while containing the seeds of corporate decor so as to make people start giving him the money to start producing more ambitiously-sized corporate merchandise.

I don’t object to “no-hands” techniques of screen printing and other methods of producing a painting–in fact the Wool exhibition made me start to think more fondly of Wade Guyton’s digitally printed paeons to corporate modernism in his exhibition at the Whitney last year: Guyton’s paintings at least gave me the eerie sensation that I was on the set of a 1960s spy caper movie, all shiny white surfaces, Knoll furniture, white shag rugs, and Marrimekko patterns, which brought back a happy whiff of being a teenager in New York in the suddenly swinging ’60s, while Wool’s paintings give off more of Bloomberg corporate headquarters vibe than Lever House or In Like Flint. And I am not looking for overt affect or an emotive artist’s hand: paintings by Isa Genzken currently at MoMA do not betray overt emotionality except in their unyielding reserve, but even those which are relatively “no hands” have an inch by inch surface tension that is riveting. Obviously my opinion about Wool differs from some of the most notable journalistic critics in New York, but as far as I am concerned these paintings have no punctum. They suffer from PDS: Punctum Deficiency Syndrome. (see my essay on painting, “Course Proposal,” when I speak of similar disorders, P.I.S., Painting Illiteracy Syndrome, and P.D.S, Painting Deprivation Syndrome).

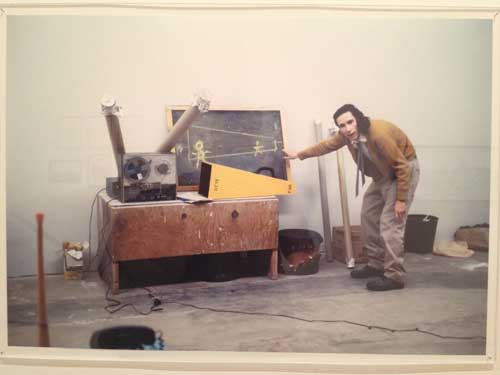

The Living At this point in the proceedings, after we passed some more black and white graffiti-inspired pseudo-edgy versions of boring later Brice Mardens and flower patterns in the genre of Phillip Taaffe, we made the detour into Robert Motherwell: Early Collages. Looking at a photograph of Motherwell in his studio in the 1940s at the entrance (and exit) of the show, I thought about the story he tells in Emile de Antonio‘s 1970 film Painters Paintings about how he had at one time used chance to select a title for a painting, as other artists were doing at the time, by sticking his finger randomly in a favorite book and had come up with the title The Homely Protestant. In other words I entered the Motherwell show with a bit of snark based on a sense of familiarity.

But the very first work I came upon, a very small ink drawing from 1941 in which Motherwell explored the influence of Surrealism, set me thinking in another direction, of a young artist trying to figure out for himself the meaning of new styles and ideas, working with sincerity as well as skill or elegance. Slightly later drawings from the period have abstracted figurative elements and bright colors I would not associate with Motherwell: a very Louise Bourgeois-like small drawing of an abstracted figure drawn in black ink is punctuated by bright pink and yellow, larger collages work with juxtapositions of patterned wall purple and white flocked paper or are built on foundations of robin’s egg blue gouache.

The museum guards were wearing themselves out yelling, “No Pictures, no pictures,” while the catalogue images were precisely unable to yield the experience of looking at the work in person, experiencing their thingness as collages, and tracing the formal decisions in details of placement and edge, so I’m sorry to say that this blog post is lacking in photography that would give a detailed sense of the visual decisions being made in each work, this scrap of cloth placed next to this map on this gouache surface next to this oil painted area, then perhaps displaced with the ripped edges showing, all small discoveries and joys in the making that may now be long accepted and even long rejected formalist ideas and yet when done with a genuine sense of discovery and pleasure have a vibrancy which may for some viewers be unexpected. But thinking back on the echoes in Wool’s paintings of Rauschenberg and Polke and a host of other artists going back to the Abstract Expressionists and to Cobra, two things seem clear: the facility of Wool’s marks, including in particular those moments when he seems to be riffing off the idea of wiping out a drawn loop of paint, is only simulacral of the notion of discovery within a painting.

The work is predicated on the risks taken by earlier artists, all the battles have already been fought, by somebody else, whereas in these early Motherwell collages you see those battles being fought freshly and with sincerity rather than with a facile gloss. The difference is that although Motherwell was also fighting battles that had already been fought, by Miro, Matisse, Picasso, Gris, Braque, he isn’t skating over slick ice yet, he’s still engaging. And this engagement yields a pleasure particular to works from that era: Motherwell was not unique in the formal parameters he was trying to figure out and in the appearance of the work–many lesser known artists of the time, including Fritz Bultman or Henry Botkin, produced works that look quite similar and they all seem to yield the same pleasure. Each artist was working on these European influences for him or herself at the same time as many came up with similar forms so that all these works also reveals the better part of an aesthetic consensus.

The charm of this work may be most keenly felt by those of us familiar and sympathetic to this consensus. But still, looking at many of the works in Robert Motherwell: Early Collages, I felt something I don’t usually associate with Motherwell: when this guy was doing these works he was really alive. That quality of life is something that never leaves a work.

The Dead Since I had already not been very enthusiastic about the Wool paintings I saw before I stepped away from the main ramp in order to see the Motherwell, I was surprised that when I stepped back into my path down the ramp Wool’s paintings looked so much worse in comparison to the Motherwell early collages. I mean, beyond worse. In some cases once I have seen something in a museum that I really like I try to put on imaginary blinders so I won’t see whatever art is installed between me and the door, but in this case I didn’t even have to make that effort. I just felt that there was nothing to see. Even the elegance of the later works pales into the most stultifying nothingness and not even nothingness made with conviction. I’ve rarely had such an experience of vacuity and I felt that no one was particularly bothering to look at the paintings, they were just walking along, up or down. If one sees Wool’s work as emerging from the moment when painting was for the umpteenth time being theorized as dead, he indicates one path taken by painters dealing with that rhetoric, which is to produce dead paintings. I lost interest in discovering that liminal work with the ineffable combo of relative edginess and the promise of corporate decoration and concentrated instead on not slipping on the last few feet of the ramp.

Even if the juxtaposition of these two shows had me convinced that in a freaky Friday sort of way, the living artist’s work was dead and the dead artist’s work was living, I still wouldn’t want to end on this binary. Nevertheless Robert Motherwell; Early Collages, which runs through January 5, is well worth seeing and these works, placed today in a small gallery on the Lower East Side, in the guise of having just come out of the studio of some young artist, would appear completely viable and credible as contemporary works because there are so many artists today, here in New York showing on the LES and Bushwick as well as elsewhere in the United States and Canada and perhaps globally, still working in the orbit of the aesthetic consensus of post-War formalism. I’m not sure what I think about what that means for painting: I often think about the durability of certain artistic traditions in the past over long periods of time with small variants based on location and time and then that a style and even an aesthetic idea would continue to be worked within and around for sixty or seventy years makes a bit more sense. Even the simulacral corporate revamping of that tradition in the genre of Christopher Wool is part of that longer term aesthetic life or even just half-life.

The Undead Between the living and the dead, a third way is offered by the retrospective of Mike Kelley at MoMA PS1. From the Homely Protestant to the Abject Catholic! If Motherwell and Wool, with roles reversed between the living and the dead, nevertheless occupy the same cultural ground, Kelley’s work is much bigger in its scope.

When I began this blog I laid out four modes of falling in love with an artwork:

1. pole-axed by an artwork greater than me. Hugo Van der Goes, Giotto, Chartres, the Stendhal syndrome, one can weep: their ambition, piety, brutality, beauty, form, matter, is a cause for wonderment, gives you food for the arduous journey of a lifetime of artmaking and being a person.

2. creative energy generated by work you dislike strongly: why do you dislike it? It must have something to do with you (there’s a lot of bad work that doesn’t bother you). Work that seems antithetical to my practice and in the end may still be so but because I don’t care about hurting it, gives me a lot of freedom to answer it.

3. the distinction the French make between je l’aime – I love him – and je l’aime bien, I like him well enough. There is much art you can like well enough: it doesn’t rock your world, still one must respect it for the valiance and integrity of its effort.

4. uncompromising works or even moments in a work to which you respond, instantly, deeply, “yes,” that make you want to go home and work. Maybe this is a form of falling in love, because the response to some people is also simply, yes, that’s it.

Kelley’s work falls into the first category for many and if I look at my own terms–ambition, piety, brutality, beauty, form, matter–these are attributes of his work. But you can see these qualities in artwork and you can admire an artist tremendously, feel strongly that he is an important artist, and still not “love” his work. That is the case for me with Kelley. But love is probably the wrong word anyway to address work driven by a powerful undercurrent of abjection and self-loathing, from some of his earliest performances to the scenarios of the massive video installation work, Day is Done. One aspect of what is so impressive and inspiring is Kelley’s ability to work in any medium and address any art history he needs to at any given moment–he simply deploys whatever style and medium he deems necessary, what any one other artist might devote a life to he is able to do, and if I say do it without struggle, in his case I don’t mean in the empty after the party is over and the battle has been won way of Christopher Wool, but as you would use a hammer when you needed one, not feeling you had to reinvent the hammer.

Also inspiring is that he totally carries every narrative and formal idea through to the max, mobilized by a strong internal engine driven by the deep manner he has experienced the conditions of his youth. In a manner that is very similar to the way Louise Bourgeois found an endlessly recharging generator in the trauma of her father’s betrayal, Kelley takes the culture of mid-Western blue collar life and the rebellious spirit he was able to maintain in its face–and makes everything from that, from his early cropophilic performance pieces to the massive performance video installation spectacular that is Day is Done. Although ur-American high school rituals as a subject have zero native interest to me, being very foreign to my own upbringing, and even though I had to leave the rooms because the noise and movement of one of the installations of Day is Done was making me physically ill, dizzy and anxious, I know it is a great piece–I don’t love it, I bow to its power.

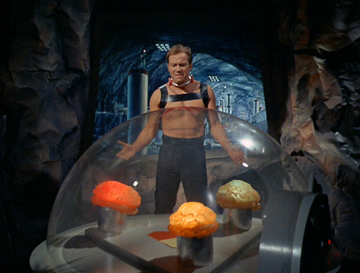

I was perhaps most interested in the late works, the very highly produced expensive sic-fi gizmos of the Kandor series. I was not familiar with these works about the survival of Superman’s home planet in miniature. Without knowing anything about them I immediately intuited that these were done under the aegis of Gagosian–their high production values seemed palpably emblematic of a Faustian deal with the Lucifer of the art world, a deal that perhaps was fatal, but Kandor was yet another subject from his youth to which Kelley dedicated several years researching and producing. I really loved the shiny weird shapes and hard surfaces and lights, the relation not just to Superman movies but to the movie Forbidden Planet and to Star Trek: Spock’s Brain might have been contained within one of these strange extra-terrestrial life support systems.

The Living

On the way into the room at the Met containing William’s Kentridge’s video installation work you pass through an exhibition of paintings from the late 1950s by Al Held, including his powerful 1959 30 foot wide paintings Taxi Cab III (acrylic on paper, mounted on canvas). Taxi Cab III looks incredibly fresh and new, with vibrant color and bold strokes. Smaller abstractions accompanying this major work manage to put Held’s boldness to the use of a kind of spiritualism akin to the more delicately crafted works of Hilma Af Klint--a strange comparison that for some reason was the first thing that sprang into my mind. These paintings are very alive. Go see them.

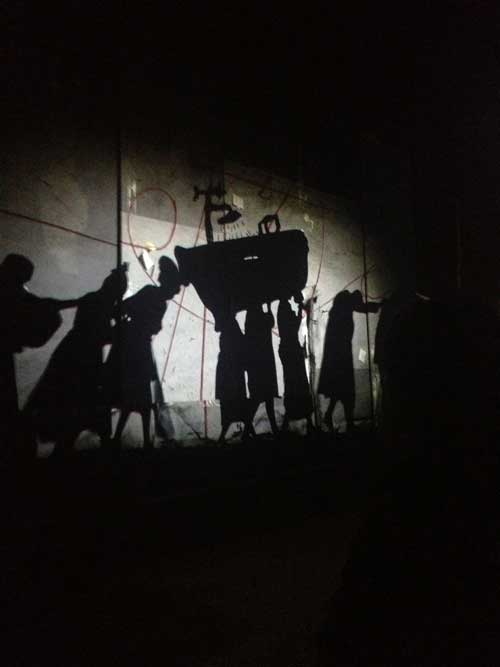

I walked into William Kentridge’s The Refusal of Time at just the moment when a silhouetted procession of musicians moved across the walls while, having been plunged into a darkened room crowded with people standing around, my friends and I had to put our hands on the shoulder of the friend in front of us in order to keep together. We were like the figures in the film and like the fools in Italo Calvino’s folk tale, “Quack! Quack! Stick to My Back” or the dance macabre at the end of Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal

In The Refusal of Time, Kentridge has created an environment like a workspace of some kind, with rough unfinished sheet rock walls, dominated by a large wooden piston-like contraption moving back and forth like a machine imagined by Leonardo brought to life yet without an obvious function. A few wooden chairs are set about the room at slight angles from each other as if they had just been in use by someone, but each is bolted to the floor so that each viewer who is able to get a seat will be looking a series of several repeated and variant video projections from another point of view, thus making each viewer’s experience slightly different than the next person’s. No matter how much one tries to see everything at once it is not possible to do so.

The Refusal of Time is an immersive multi-media 30 minute experience with music and sound. A variety of scenes and narratives take place like movements of music, which include many of Kentridge’s motifs and techniques, beginning with himself as a performer in his own studio, very plain yet Chaplinesque, and expands to a number of silent film style vignettes, all in black and white, in shallow paper and cardboard painted sets reminiscent of early cinema, of Lumière movies, of Diaghilev and The Rites of Spring, and of homages to these earlier modernist works by artists like Red Grooms and Mimi Gross in Fat Feet. These scenes expand into a complex variety of expressions and enactments of drawing, the hand of the artist with an old fashioned fountain pen drawing on the page of an old school notebook a diagram of the earth with radiating lines emerging from it shifts to the hand of the artist creating swooping soft loops of white paint that swiftly move towards you like the Milky Way on a dark clear night–that particular sequence made me think of Wool’s use of looping forms: with Wool, you think empty lobby, with Kentridge you think, the Milky Way, the cosmos.

Kentridge uses established media and tropes of all these media and art forms without giving up on any of them or deploying them with the distantiation of irony or cynicism.

It is hard to take in all at once, and hard to pinpoint the exact subject matter, it is specific yet abstract. It must be seen more than once, and seen through from beginning to end, so be prepared to come in, stand around and wait until the loop is done, try to get a seat and then watch the whole thing through.

At the moment one image that has stayed with me is of a man being dressed up as planet Earth in a huge billowing balloon of a costume which jiggles as he begins to dance with joy.

This is not art that sets out to kill you, it is not about the artist assaulting you with his ego–this is something I always am struck by when I see work by Kentridge including when I have seen him perform in person. The artist Tom Knechtel has said that Kentridge turns himself into a lens through which we his viewers can see the world. Above all his subject matter is the act of artistic creation and thought. At the end, seeing the silhouetted line of musicians in diagetic context, it seemed as affirmative as it was also about the absurdities of human effort, a joyful and triumphant Dance Macabre.

The Refusal of Time is a joint acquisition by the Metropolitan Museum and The San Fransisco Museum of Modern Art. Go see it now while it is up in New York.

Robert Motherwell: Early Collages is up at the Guggenheim through January 5, Mike Kelley is at MoMA P.S.1 through February 2.