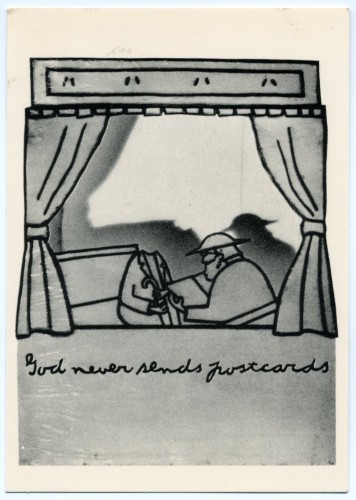

This blog contains some embedded film clips that can only be viewed if you read the blog post online at A Year of Positive Thinking, rather than in your email if you are a subscriber. Just click on the logo for the blog which will take you to the online version.

Shortly before the first Presidential Debate September 26th, one of my students told me that he felt that the American system of government was sturdy enough to withstand the depredations of a Trump presidency, not that he was for such an event but in response to my fear of a fascist take over of the government. I thought about some of the times in recent history when in the face of attacks on some of the basic principles of our Constitution, the “system worked.” Watergate is frequently mentioned as an instance when “the system worked,” when some members of the legislative, executive, and judiciary branches of government and some of the press were able to stand up to Richard Nixon’s abuses of power. Thinking back on those historical instances, I wondered whether the same mechanisms would prevail now, and that led me to thinking about a few movies that are part of the filter through which I see our current political crisis. The movies I have chosen were mostly made in the period between 1964 and 1976, and are historically bracketed by the Cold War and the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 and the Watergate affair of 1972-1974. At the beginning of the cycle, the President of the United States is portrayed as a hero, the final film of the cycle (Network, 1976, see below) is post national and post governmental, and the nuclear bomb has receded from view as a fear, replaced by the madness of corporate greed.

At the center of my student’s faith in the American system of government is its tripartite system of balanced powers, where governmental power is divided between the Executive, the Judiciary and the Legislative. In a sense this is a system with a fail-safe mechanism built in to prevent the kind of monarchical tyranny the American Revolution emerged from.

The failure of such a fail-safe system is the theme of the 1964 movie Fail Safe in which a group of Strategic Air Command planes carrying a nuclear response payload cannot be persuaded to turn back in time to stop an unintended, mistakenly triggered, first strike on Moscow. The basic premise is not unlike that of Dr. Strangelove, released the same year, except that in Fail Safe it is played for realism rather than satire. As the planes head for their target, the fate of the world rests on a Solomonic choice of public and personal sacrifice made by the President of the United States. Fail Safe, directed by Sidney Lumet and starring Henry Fonda, with an outstanding supporting cast of mostly New York theater- and early television drama-based actors, has a taut, spare editing style possibly based on the the style of 1950s live television drama. The film begins on a fascinatingly Bunuelesque note and the use of a beautiful 1950s style typeface for titles indicating location and time suggest a TV newscast or documentary of the period while stylistically pointing us forward towards the use of text titles in the films of Jean-Luc Godard. (just a cautionary note that the version available on YouTube has been sped up so that the actors sound like Alvin and the Chipmunks in order to get around copyright laws so I hope there is another way of watching it!).

Though it was released earlier than Fail Safe, Stanley Kramer‘s 1959 film On the Beach could function as a sequel to Fail Safe in terms of the plot, that is in terms of what happens after nuclear catastrophe, as a wave of air-born lethal radiation makes it way to the last outpost of living civilization, a film produced in a time of perhaps greater anxiety about the possibility of nuclear war–the Cuban Missile Crisis was defused through the basic reasonableness and cool of the two world leaders involved and some of their advisors and marked the beginnings of a slow detente with Russia (one which apparently has now eroded back into a war which most of us were too busy to notice or take seriously until this election cycle revealed it). In both these films the fail safe is human decency and the ability of some human beings to think in terms of a greater good and yet in both Fail Safe and On the Beach the very existence of nuclear weapons insures eventual catastrophe whether by will or by technological or human error.

*

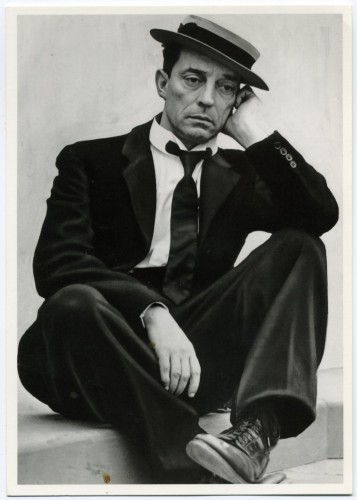

Another fail-safe mechanism built into the American system of government rests in the tradition of a military that at least in principle and according to the Constitution is apolitical. The possibility that such a policy–written into Article II of the Constitution which states that the commander in chief is the President, a civilian–might fail is the subject of the excellent political thriller Seven Days in May, from 1964, directed by John Frankenheimer. Seven Days in May details the discovery of a secret plot led by a treasonous general on the Joint Chiefs of Staff, played by Burt Lancaster, to stage a coup d’état from the far right and overthrow the President of the United States who has recently signed a disarmament treaty with the Soviet Union. The story is set in 1974, ten years in the future from the release of the movie, thus it is a kind of of science fiction thriller although it feels very much as a 60s movie in other ways, including being a black and white film and because the crisp pacing of the plot premise, day by day, hour by hour, has a technocratic aspect that seems very much of its time, and, again, emerges from the live television tradition of New York-based 1950s drama. It is notable again because of an outstanding ensemble cast where the leading characters are all movie stars, both present and legendary, including Douglas and Lancaster as well as Frederic March and Ava Gardner, in a late career role which plays on the vulnerability of her ageing beauty (no plastic surgery). The differing acting styles of these major figures within a tight and dramatic script is very interesting to watch.

The film is based on a book written in the immediate aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Apparently President Kennedy read the book and thought it presented a credible scenario, he wanted the film made according to Kennedy advisor and historian Arthur Schlesinger. Lancaster’s character was partially based on General Walker who was forced to resign after the Cuban Missile Crisis –the recent history of McCarthyism in the United States is also part of the story. In the parlance of that anticommunist era, the President is considered a “weak sister,” a communist sympathizer or appeaser.

In the film there are three Fail Safe mechanisms in play: first the military code with regards to political activity–this is represented by the Navy officer played by Kirk Douglas, who uncovers the plot to take over media communications and overthrow the President when he is mistakenly allowed to overhear a reference to a military plan or group with the acronym of ECOMCON (Emergency COMmunications CONtrol). Never having heard of this group and finding no records for it, he overcomes his loyalty to the military and to the superior officers he serves, alerts the President, and ultimately confronts the General, his former mentor. Loyalty is a theme of the film: to whom are you loyal? to your country? to your friends? to the Constitution? to the code of military conduct? to your Commander in Chief? Douglas’ character is torn between loyalty and military hierarchy and greater loyalty to the President and the Constitution, even though he personally doesn’t approve of the President’s policies. A key scene between Douglas and Lancaster involves a discussion of who is the Judas but it is clear that Douglas’ character adheres to constitutional divisions of power.

The military’s relation to politics has played a part in the campaign for the presidency in 2016: since no officer currently serving is allowed to express a political view except as a personal choice, the war of surrogacy has been waged by battalions of retired four star generals and admirals who have declared their support for one candidate or the other. At one point in the campaign, Trump said he would fire all the generals whose views he doesn’t agree with although the legality of such an action is questionable. Some former commanders have protested Trump’s statements in favor of torture and of killing families of suspected terrorists, because these would contravene the Geneva convention and the military code of conduct. Therefore it is very likely that the military could find itself, in a Trump administration, in the position of having to refuse to follow orders or even in the position of deposing the government in order to save the world from, say, nuclear warfare, as in Fail Safe. Who would prevail in today’s military? And would such officers as would find the orders illegal be likely to engage in the ultimate illegal act of taking over the government? I am not aware of any such major plot in American history: if any military coups were ever considered, they were prevented. So the Fail Safe of the military has not been publicly tested.

The second, related, element at play in Seven Days in May is human decency as it is expressed in a politics of peacemaking: this is the role of the President who is willing to lose everything in order to take a principled position for peace, one where he has not resorted to common blackmail even though that is a path offered to him, and it is also the role of his personal friends, long time political loyalists that he knows he can rely on implicitly and who risk their life for him.

The third element is chance, including a crucial letter found at the very last minute at the site of a plane crash, which plays a major role in the resolution of the crisis. This is the centuries old plot device of the Deus ex machina, when mortals fail and there is no other alternative but an intervention of the Gods, if you want to avoid a tragic ending. Unfortunately the device of Deus ex machina, the God figure literally being lowered to the stage from the upper regions of the proscenium theater just in the nick of time to resolve the unresolveable dramas of mortal human beings is not a Fail Safe device that is operative in real life. And one can hope for human decency, but it may not in the short term prevent catastrophe.

*

The phrase “the system worked” entered into public discourse most notably to refer to the resolution of the Watergate scandal. Among the elements of the system that “worked” were the refusal of some high placed government officials who resigned rather than follow Presidential orders against their own conscience and sense of proper government–these included Attorney General Elliot Richardson and Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus who refused to fire Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox, on the night of October 20, 1973, in what came to be called the “Saturday Night Massacre.” In 1974 during the House Impeachment hearings, some Republican Congressmen did vote for impeachment. The refusal to this date on the part of the entire Republican leadership in Congress to withdraw their support for Donald Trump in the face of now countless attacks on the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution makes it doubtful that such principled bipartisan behavior could occur in our era. The history of the Republican Party’s move to the far right is too long to go into in this post.

During Watergate, the press was one of the major systemic forces that “worked.” Thus Alan Pakula‘s 1976 film ” All the President’s Men, the dramatization of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s account of their investigative reporting of the break-in at the Watergate, is another movie that is required viewing while considering whether the system would work in a potential Trump presidency, that is whether the establishment press still can function as a Fail Safe to tyranny. Even though we know what happened in the story, the atmosphere of the film is one of tremendous suspense and tension, with the particular power of 1970s film noir. The movie in fact is referred to as part of Pakula’s “paranoia trio,” including also Klute (1971) and The Parallax View (1974).

The press is represented through several stock characters of movies about media–comedies such as Front Page and His Girl Friday as well as more serious newspaper stories such as Call Northside 777—the gritty beat reporter, the gruff no-nonsense editor, the unflappably competent and cautious assistant editors, the courageous newspaper owner–except in the case of All the President’s Men, these were real people–publisher Katharine Graham, executive editor Ben Bradlee, junior beat reporters Woodward and Bernstein–who each played their appointed role in the drama so that investigative reporting, Freedom of the Press, and political justice prevailed. In fact at all times in American history yellow journalism has thrived along with valiant socially conscious journalism. But the current media atmosphere is exponentially more complex, virulent, profit oriented–well, you know, we all know. And in the time of Wikileaks, what Woodward and Bernstein did may seem primitive though one can see the same kind of shoe leather beat journalism in the recent work of Newsweek’s Kurt Eichenwald and the Washington Post’s David Fahrenhold among others have done in researching Trump’s finances and ties to Russia over months of investigative research. Nevertheless during the campaign of 2016 even generally respected news organizations have alternated between this kind of responsible reporting and cowardice.

Meanwhile Trump has made it clear from the start that he would try to destroy a free press. Actions including having reporters thrown out of press conferences, barring news organizations from his rallies, encouraging violence against reporters at this rallies, insulting female reporters, threatening to sue newspapers, are listed in a statement released October 13, 2016 by the Committee to Protect Journalists, declaring that “a Donald Trump presidency would represent a threat to press freedom.” As an example of what might be, last week the press covering a Trump rally had to be escorted by armed guard to their cars and buses. One has to worry about whether the press of record, the press with an established ethos of investigative journalism, would be able to financially survive a Trump Presidency. So the fail safe of a free press under a Trump administration is uncertain.

When such threats are made, one always has to worry about self-censorship. In his 2005 film Goodnight, and Good Luck, George Clooney, speaking as CBS News hero Edward R. Murrow, says during a staff meeting of his CBS News show See it Now, as they consider whether to go after Senator Joe McCarthy—“the terror is right here in this room.” Goodnight, and Good Luck is another useful film to view in relation to trust in a free press or media as a Fail Safe. Murrow did play a role in at last dismantling McCarthyism, through his See it Now broadcasts of 1954, and the courageous editorial statements on that program, but from a corporate media point of view this was also one step towards a more profit-oriented news organization as Murrow was gradually marginalized within the network after his heroic moment. Murrow had earned the respect of the American people through his courageous broadcasts from London during the blitz, and he set a standard for reporting that was carried on by a younger generation, now mostly deceased. Only Dan Rather survives of the generations of reporters even remotely connected to “Murrow’s Boys” and, remarkably, at age 85, he has been publishing strongly worded condemnations of Trump on a Facebook page. Murrow’s original March 9, 1954 broadcast can be viewed here, and his comments after McCarthy responded can be viewed here. If you watch Murrow’s initial broadcast taking on Senator McCarthy, which I recommend doing, you will ask yourself whether the contemporary media would be capable to be able to deliver such a report with such seriousness and with such moral authority though a few television reporters are rising the occasion. Significantly, in terms of the historic nature of this election with one candidate being the first woman to be nominated by a major party to run for the position of President of the United States, many of these are women, including Katy Tur, who is the long suffering, often under attack, indefatigable reporter assigned by NBC News to cover the Trump Campaign.

Please note that there is a direct line between the McCarthy era, as seen both in the archival footage and the recent movie, and Donald Trump since McCarthy’s despicable aide, Roy Cohn, was an important mentor to Trump early in his career.

Clooney’s deliberate use of black and white film in order to give authenticity and recognizability to the historical recreation connects him to such notable documentaries as Emile de Antonio’s 1964 documentary film Point of Order, about the Army-McCarthy hearings. It is also an homage to the generation of producer, directors, and writers that made the films I have already mentioned: Sidney Lumet, Alan Pakula, Stanley Kramer, John Frankenheimer, who all belonged to a generation with its roots in the Great Depression-whether their families were personally affected by it or not they were raised within an atmosphere of left-leaning social consciousness and activism which permeated their work. These were men who had a politics, a political world view of sympathy for the working man and suspicion of political authority and abuse. Somehow they had managed to avoid the worst effects of the blacklist on the late 40s and early 50s in order to produce these works. Many had worked in theater and in early television live drama, whose style and editorial pacing permeated their films, including the cast of theater actors they relied on as a kind of repertory company floating between them, many from the Actor’s Studio, and in several important cases the use of black and white not just for economic purposes but for its political and historical qualities at a time when color was readily available.

A final, more chilling and more contemporary film also made from this political generation is Network, from 1976,written by Paddy Chayevsky, another member of this theatrical and cinematic generation, and directed by, again, Sidney Lumet, which examines the lengths to which the ratings-obsessed value system of contemporary broadcasting will go to protect and advance corporate interests. The script is ready for our current media atmosphere: Lumet and Chayevsky would not be surprised that a TV Reality show star is running for President as scripted by a “reality”show driven by ratings more than political belief. Network forms an incredibly smart bridge between what Guy Debord described in Society of the Spectacle and the media environment of our time, most powerfully in a monologue delivered by the media corporation CEO to the deluded insane news anchor Howard Beale. The second part of his remarks are particularly notable.

*

The power of the media to create a popular, populist star and then reveal the cynical indecency of a media star is the subject of A Face in the Crowd, a 1957 film directed by Elia Kazan–a man whose reputation was and still is marred by his having named names to the McCarthy panel. The film questions the role in our political system of the newest most powerful type of media at that time, television.

Marcia Jeffries, a young woman reporter working for a local radio station in the South, looks for local color in a county jail in Arkansas, where she spots the raw talent of Larry Rhodes, a guy sleeping off a drunk. He has charm, a downhome sort of wisdom, he can sing and play the guitar, and he is young and ruggedly attractive. It may come as some surprise that this role is played by Andy Griffith, but seeing the movie will make you think very differently of him as an actor. His characterization has an overripe brutality which may seem over the top but given the ongoing spectacle of Trump, maybe not. And it works in the film.

Jeffries manages his career as he rises to television stardom as “Lonesome Rhodes,” a catchy nickname she has given to him. His persona trades in what at first seems like genuine authenticity. He sings while making folsky asides which endear him to the radio then the television audience. Gradually his success goes to his head, he believes his image. He gets involved in politics, at first as as a media advisor to a Senator with aspirations to higher office. His behavior is increasingly thuggish and cruel. Eventually the woman who has created him now sees that she must destroy him, for the public good. Her decency is wrenched from her sexual enthrallment to him–the film is as explicit about that as could be portrayed in American film at that time, with Patricia Neal at her most beautiful and as always with her sexual nature vividly evident, as in some of her other notable film portrayals, including her roles in The Fountainhead and Hud. She could do more with her eyes, her body, and that black slip than anyone. She pulls the plug on him on by turning on his mike when he thinks he’s off the air so that his audience finally hears the contempt he has for them, hears him as he really is, the “monster” that she herself had created by lifting him out of the crowd.

I have thought about this movie often in the past few months: it seemed as if Trump was revealing how awful he was for everyone to see and to hear every day so that there could be no possibility of such a revelation, what else was there to reveal: thus the movie’s faith in people’s ability to be shocked seemed quaint. Then Access Hollywood‘s “grab them by the pussy” live mike video and audio turned the tables and seems to have worked almost as well as the live mike in A Face in the Crowd in turning at least some percent of the population against Trump.

One can only hope that the final scene in the movie is also predictive. I strongly recommend the film so I don’t want to spoil it except to say that the end involves a lonely has-been television personality howling from the penthouse terrace of a luxury apartment building in midtown Manhattan.

*

So far nothing that has been revealed about Donald Trump, from his sexually predatory behavior to his ignorance about policy including his casual interest in the use of nuclear weapons have had a definitive effect on his candidacy. Revelations in the press have had a limited impact: as of today polls show him still as having 43% of the popular vote. The press was slow to act and Congressional leaders from his own party have not shown the political courage to stop supporting him.

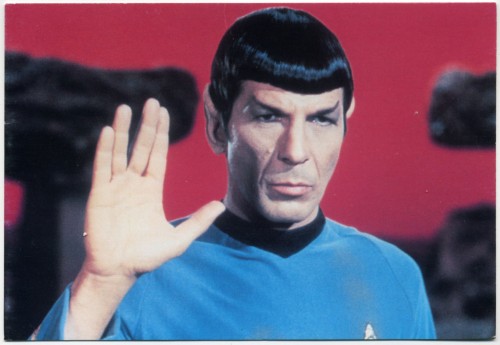

As for Deus ex Machina, the gods sometime wait quite a long time before intervening to save humanity: this is the case in an early episode of the original Star Trek series, The Squire of Gothos, where the Enterprise and its crew are hijacked and kidnapped by a being, humanoid in appearance but not registering as a living being on the crew’s tricorder devices. He lives alone in some splendor and seems to get his power from a full length mirror he never strays far from, the classic narcissist that all have diagnosed Trump as being. He toys with the crew, impedes their escape, and eventually threatens their life. At the last minute, two “energy beings” appear (disembodied voices represented by light) and apologize for the behavior of their “child.”

So far, Fred and Mary Trump have not appeared to discipline their child and stop him from endangering the Republic, which they were apparently unable to do in his youth, sending him to military school when all else failed.

*

These are just a few of the films that have occurred to me when thinking of the fail-safe mechanisms built into American government and other major institutions that in the past may have averted political catastrophe. If my readers can think of other films with this focus, please email me about them and I may collect them into a second blog post. I am writing this before the third debate. Who knows what new abomination may befall us next during this campaign?