I have often wondered how many people in the metropolitan area saw some part of the events of September 11 in New York City with their own eyes, from streets and buildings in Manhattan, from Brooklyn, from New Jersey. Was it a million of us? Was it more? I have never seen speculation on the numbers in the press. The number of people who, living and working in the city in the following weeks, experienced the ruins, the smells, the air quality, the police and army, the frozen zones, the rerouted slow subways, was much greater. But for many others, the less you saw with your own eyes and the farther you lived from the immediate neighborhood, the more abstract the events became, the more September 11 became a spectacular media event which could eventually blend into others.

I was one of that indeterminate number of people who witnessed some of what happened that day “with my own eyes” and lived in the city and near Ground Zero in the weeks after. At the time, I lived in Lower Manhattan. I heard the first plane fly over and hit the North Tower. I saw the explosion from the impact of the second. I lived in the “frozen zone.” My loft would fill with the indescribably sickening smell wafting northward from the site on late night currents of air. In the weeks after September 11 I worked on an email about the events of day and life downtown in the days and later the months following. In those early days, writing it was my principal occupation and I wrote to preserve the details of each day. This text began its life as an email to friends that circulated around the world and returned by email to my downstairs neighbor, stripped of my name. That anonymity was fitting because mine was just one of many such accounts,many much more dramatic than my own, and they all begin the same way, “On September 11, I was… .” I published it as “Weather Conditions in Lower Manhattan–September 11, 2001, to October 2, 2001” in A Decade of Negative Thinking, a book written in the aftermath of that event, many essays in it marked by the way it (as the first in the chain of a series of events) affected my perceptions of contemporary art in the months and years to come. I also have published excerpts of this chapter as a Facebook Note.

Much has happened in the years that separate then and now that has become more important than the event itself, most notably the criminal and ruinous wars that the Bush administration launched within days and months, but also the subsequent transformation of the country into a polarized and ideologically damaged state, while the site of the World Trade Center has mutated from an awesome and infernal mountain of burning steel and toxic ashes to a battleground of real-estate interests and compromised architectural and design programs. The New York Times has just published an excellent summary, The Reckoning: American and The World A Decade After 9/11, as a supplement in the Sunday edition of September 11, 2011 (get the actual newspaper, it makes more sense to hold it in your hands).

As I had suspected would happen when I wrote that email in September and October 2001, the details of everyday life in New York City that day and in the days after do gradually fade from memory for many. Many horrible things have happened since, both public and private traumas that layer over and even replace that one. But for some including the confederacy of witnesses the memories remain intense though inevitably altered by time and history.

Here are photos I took day by day, with excerpts from my initial writing and some annotations from today. These aren’t great photographs, I had a point and shoot film camera that I carried around because I needed to document what I saw. My experiences were neither unusual or dramatic, but I hope they allow a glimpse of the texture of daily experience in an unusual time in this city. I have placed some of the text in captions, some in the body of this post. These are in italics and comments written today are in plain text.

*

In 2001 I lived in Lower Manhattan, on Lispenard Street, which is one block South of Canal Street, 14 blocks north of the World Trade Center. At about 8:45 AM on the morning of Tuesday, September 11, I was still in bed and had just turned the radio on to WNYC, the NPR affiliate in New York City.

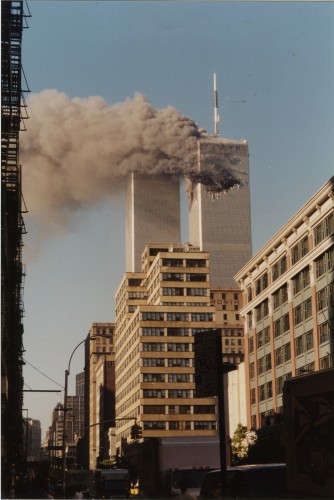

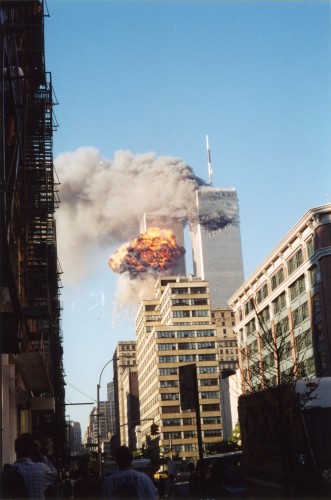

I heard two sounds, some kind of muffled roar and then a thudding crash. This neighborhood is incredibly noisy so it could have been a truck crashing into something on Canal but the noise was notable enough that it crossed my mind that it might be a building collapse in the area. After the interval of time it took for that image to cross my mind, within less than a minute of the sound, an announcer on WNYC yelled that there had been an explosion at the World Trade Center. I rushed into my clothes, grabbed my keys and my camera, ran out the door and got to the corner of Lispenard and Church by about 8:57 AM. This is the corner from which the video, which I would call the “money shot”, of the first plane crashing into the building was filmed.

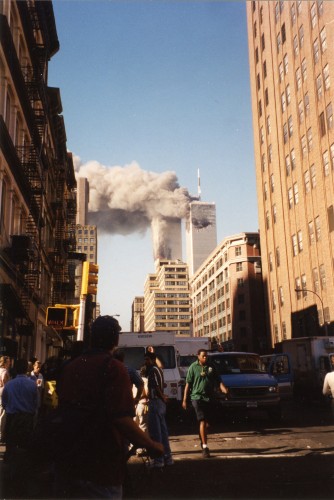

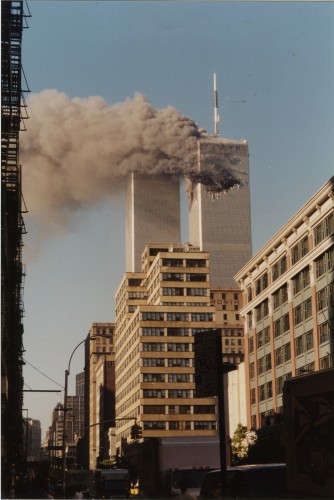

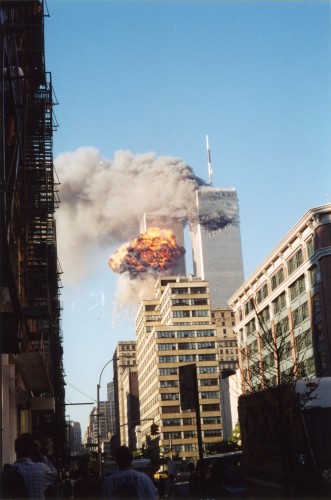

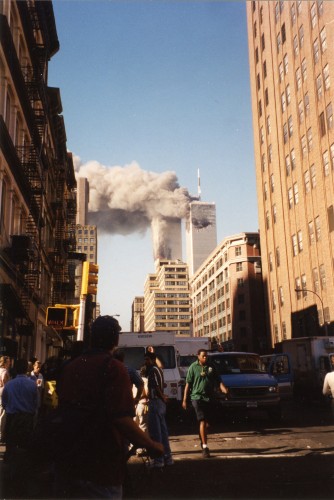

Approximately 9:03.30AM-In the sequence of pictures I took from the moment I reached the corner, between the 6th and the 7th picture there is a gap which represents perhaps twenty seconds, during which an enormous explosion on the left side of the South Tower expanded and engulfed the entire top half of the building in a giant ball of flame before subsiding into flames and smoke. During this time I forgot I had a camera.

c. 9:20AM

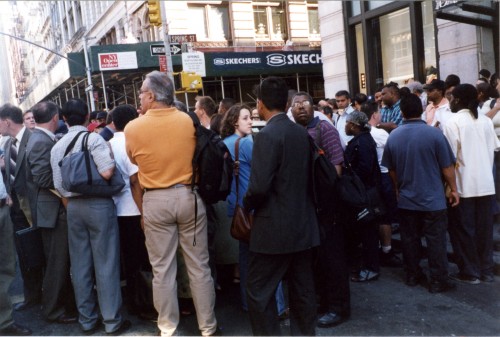

c. 1:30PM-About 40 minutes after the collapses, knowing the city was being closed down, I decided to go out to get food and cash. It was a beautiful day in New York City, clear, mild and dry, the kind of day when the postcard pictures are taken and when the air is most pleasantly compatible to the inner temperature of the human body. Where the Towers had stood the sky was a gorgeous blue with just a low movement of the ochre/gray dust toward Brooklyn. Completely surreal, unreal, nuclear.

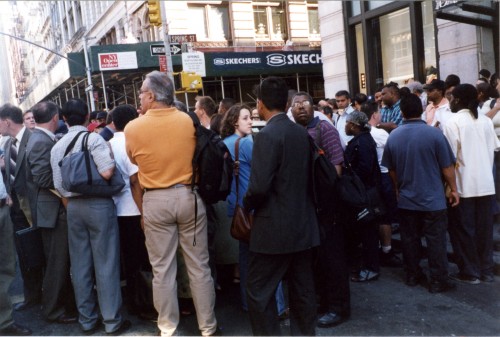

At the corner of Spring and Broadway, the streets already emptied of all traffic, a guy had pulled over his SUV and turned his radio up. A crowd of about thirty people listened. In the midst of all the confusion, a lady took the time to warn me that my bag was open.

...a tall large man stands apart, looking back downtown. His suit is covered with ash. I realize that no one spoke to him.

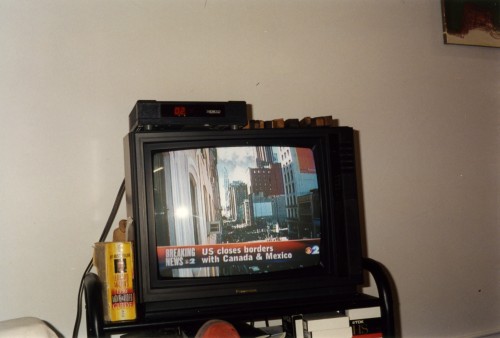

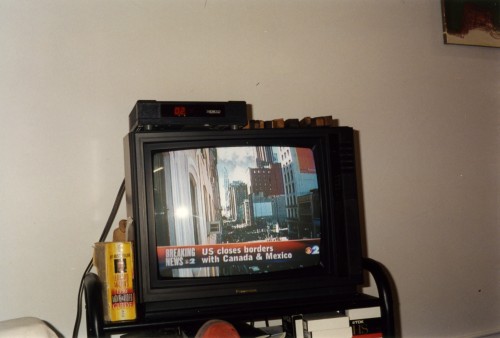

Television news bulletin September 11, mid-afternoon

I went out again at dusk: at the corner of Church and White the temperature suddenly rose about ten degrees.

September 12: for the next few days they started dumping wrecked vehicles on avenues north of the site, to begin to clear out whatever could be moved easily. Here's a guy rummaging through the toxic dust of a destroyed car, placed on Church street, near Apex Art.

September 12, nighttime. Church and Canal Street and also Lispenard STreet, just South of Canal became a NYC and State police and National Guard incident center. The last National Guardsmen were pulled from my corner one night in late January. As a woman living alone in New York City I probably never felt as safe (nor yet as creeped out).

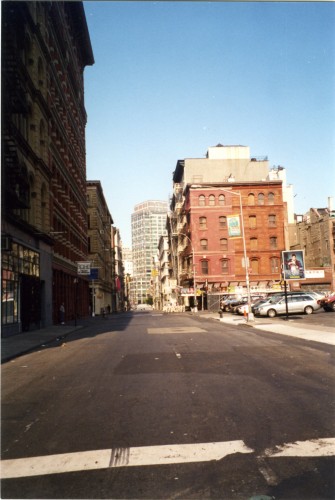

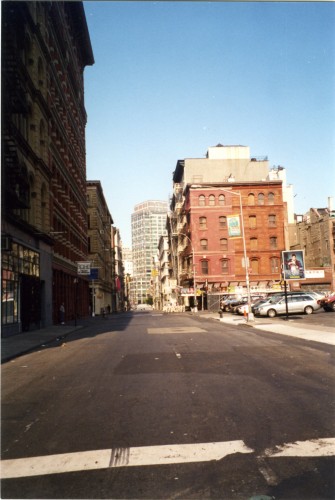

In 1950s movies, the aftermath of WWIII might be indicated by a vacant Wall Street filmed at 5 AM on a Sunday morning. That’s what the streets of Soho looked like. You could have shot a canon down Grand Street and lain down to sleep in the middle of Broadway. This desolation was one of the most memorable aspects of the few days after September 11–strange and disturbing and yet in a way extremely beautiful, almost pleasurable, something like the dream of being all alone in a great museum, able to wander at will.

September 13, 2011: Looking West down Grand Street from Broadway

September 13, Grand Street looking East from Broadway

September 13, 2001: Looking south towards the WTC site from Grand Street and Broadway

September 13, 2001. Looking north from Grand Street and Broadway to where the sky was clear and blue

Looking back downtown from near the Public Theater south of Astor Place. The line of demarcation of the "frozen zone' still was at 14th Street. It was hot and the air became increasingly hard to breathe as one got further downtown, closer to the site.

September 13, 2001: I stopped at Dean and Deluca on the way and enjoyed an ice coffee and the beauty of a row of some kind of red bottled liquid arrayed in a row on an upper shelf illuminated by the bright lighting in the store. I asked workers there to wet a paper napkin to cover my face so that I could breathe as I walked the final blocks home.

September 14, 2001: Impromptu memorial at Washington Square, detail

September 14, 2001: Impromptu memorial at Washington Square, detail

September 14, 2001: to the South, only a great gap where the Towers once had been my beacons homeward.

For comparison, and because the minute the towers fell it became impossible to accurately remember where they had been, here is a picture I found on the web about a year ago, taken from a half block south of the previous picture, West Broadway, just below Houston, looking South. [See also Jonas Mekas’s beautiful visual tribute to the Towers which continuously re-situates them in that gap of memory.]

View taken sometime in what appears to be the late 70s or early 80s, looking south on West Broadway, just below Houston. Only the bottom third of the Towers are visible in the icy mist.

September 16, 2001: crowd on the north side of Canal Street above Church Street, assembled as close as non-residents were allowed, straining to see the site.

During this particular period, networks and cable news reporters filmed from that corner, including one CNN reporter on the roof of one of these buildings, so I would see them “live” and go home and turn on the TV to see them “live.” My relation to media coverage was unique to my previous experience in that my neighborhood was the news, and yet at times I experienced some of what happened exactly as if I had not been living there (for example, I watched the towers fall on TV because I had returned home to make phone calls to family) and sometimes in this amusing co-presence with the reporters.

September 17, 2001: view South from the roof of my mother's apartment building on West 79th Street.

MONDAY the 17th I went uptown to see my mother. It was the first time I had strayed north of 14th street, first time on the subway. I thought I was calm, “normal” but her neighborhood was “normal” enough to make me realize how crazed I really was. The crowds at Zabar’s shopping for the holidays made me scream with impatience. The subway ride up had been quick and simple but the ride back down was terribly tense, the old A train was very crowded but when we slowed down every few minutes in some tunnel or other the car was silent except for the babbling of toddlers. At West 4th Street it was announced that the train was going to be diverted so I had to walk home from the village with my groceries. The conditions in my neighborhood were intense, police barricades, the rescue effort vehicles, the epic scaled recovery and repair work, the smoke. God knows what we were breathing, but I found the Upper West Side’s relative normality disturbing.

Now I live on the Upper West Side. This will be the first September 11 where I do not live downtown and the sense of separation from the site and the neighborhood is a continuous lack. But when I looked at the picture of the skyline looking south that I had taken on September 17, 2001 from the roof of my mother’s building, it occurred to me that I had no idea if the towers had ever been visible from that spot. Now I live in the same building and I asked my neighbor today, and not only could she affirm that they had been visible but she found a picture she had taken from her apartment on September 11, before the towers fell.

September 11, 2001, view in the distance of the burning North Tower, possibly before the South tower was hit, from West 79th street, taken with a telephoto lens. Photo: Karen Cornelius

September 22, 2001, Ad for "24", corner 28th street and 6th Avenue

This ad for 24 seemed to me like a big nasty insulting joke when I first saw it on September 22. “This fall, prepare yourself for one unforgettable day.” That horse had left the barn, we had had our unforgettable day, thank you. Only today does it occur to me that the show, which premiered November 6, 2001, had been planned and begun filming long before September 11, 2001. It seemed to spring from the events of September 11 and after, and it seemed emblematic of a type of paranoia, violence, and forensic gruesomeness that has permeated television drama in the past decade. The first CSI series had begun a year before but it held a particular fascination afterward, providing a scientific and technical frame for absorbing the details of DNA identification of the shreds of remains found at Ground Zero. I’ve sometimes thought of this past decade as the decade of Jerry Bruckheimer, producer of CSI, CSI: Miami, Without a Trace, and CSI: New York. These dramas all present a similar vision, of a world darkly lit, filled with menace, even though the stories are related through the seemingly reassuring point of view of agents of law enforcement engaged in scientific analysis of forensic evidence. Without a Trace and CSI: New York in particular rely on a vertiginous aerial approach from high above the skyscrapers as an introductory shot, a framing, and a interstitial narrative device: the camera is an all-seeing eye which swoops down into the city, particularly notable and potentially menacing to anyone who lived in New York City during September 11 and in the surveillance environment of post 9/11 America and the Patriot Act. Yet the absolute density of events and emotions of the actual unforgettable day, September 11, the pictures, the voices, the millions of individual stories against the transformative view of a previously neglected geopolitical background, have not been matched by these popular fictions.

September 28, 2001, Barbara Siegel, Elise Siegel, Susanna Heller, Nancy Bowen in front of work by Nancy Davidson

September 28, 2001. Chelsea, from l. to r, Susan Bee, Barbara Siegel, Elise Siegel, Susanna Heller, Charles Bernstein, Nancy Bowen.

Susanna, Nancy and I met at Nancy Davidson’s opening on the 28th, where we would have all met on September 11. Everyone there was very happy to see each other. As for many of us, it was the first time I was out in the city after dark, other than standing at Lispenard and Church. We had a nice dinner, although all we talked about was it, from every angle of conversation possible. At about 10 PM as we crossed Ninth Avenue at 23rd we heard sirens. A motorcade approached as if for a visiting dignitary: an unmarked black police car with red light flashing on its roof stopped downtown traffic in mid-intersection. Three motorcycle cops, then at least six more passed preceding an ambulance, which was followed by a state police car and a NYPD police car. When they find the body of a policeman or fireman, they give the ambulance trip to the morgue an honor guard of three motorcycles so this seemed even bigger and yet it wasn’t even anything that would ever be on the news. Thinking about that day in Chelsea, I’m reminded of “Quack, Quack! Stick to My Back!” an Italian Folktale retold by Italo Calvino: a good witch gives a young man a magic goose and a formula to win the hand of a princess who has decided, “I won’t laugh even if my life depended on it.” One fool after another is glued to the goose and to the person before him until a chain of fools causes the princess to roar with laughter. I’m not saying my friends and I were fools exactly though we do look almost incongruously happy: we were happy to get out, to do something, to see each other again, and we were in a state of elation fueled by shock. But as the day progressed we formed a growing chain, as a group of 3 became 5, a group of 5 became 7, and then 8, and we all stayed together as we went along. But at the same time, already that day there was a sense of aesthetic rupture: the galleries were filled with art that had been made before it, much of it relying on trite tropes and recipes that now felt intolerable.

Fall 2001, seen from Liberty Street: the great standing ruin of the South Tower, a magnificent trace of modernism, Mondrian's Boogie Woogie meets Smithson's "Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey, " the grid undone. After looking for awhile a friend said, "It's something else." And that is exactly it, you see something, but what you see bears no relationship to what was. You think, if I get closer, if I get on top of it, maybe then I will understand and yet even what I did see I couldn't understand.

May 29, 2002, there was a motorcade on Canal Street escorting the last steel beam from the World Trade Center out of Manhattan. Canal Street, normally an interstate highway, was cleared completely in both directions between the Holland Tunnel and West Street and the Manhattan Bridge

The last beam was covered with a flag and flowers, laid over a black cloth, like the casket of Princess Diana. After it passed, traffic returned and city life resumed.

*

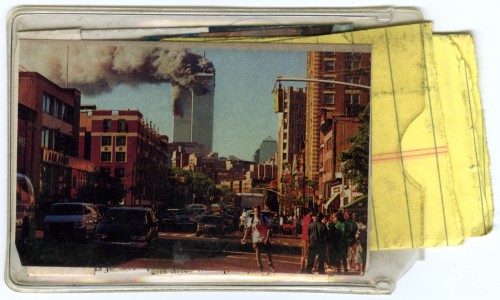

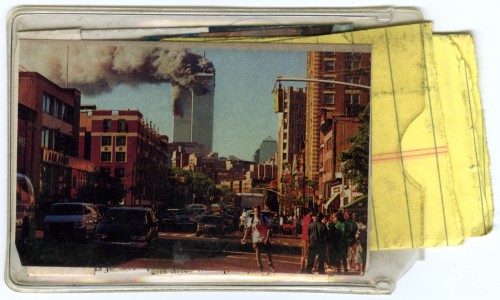

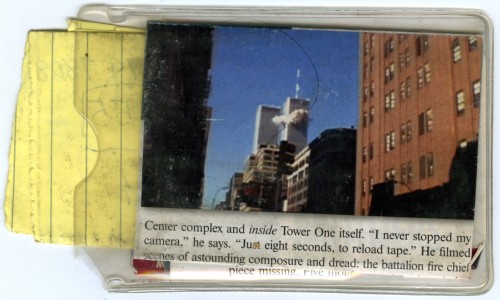

To this day I carry in my bag these two scraps of images stuffed into a small plastic ID sleeve:

Twin Towers, September 11, seen from just below 8th street and Sixth Avenue

Newspaper article with reproduction of the still from the documentary being filmed on the morning of September 11, 2001 by George and Jules Naudet, taken from the corner of Lispenard and Church Streets

*

This year may mark the last year of The Tribute in Light. I wrote about this great art work here last September 11. It would a great loss if this brilliantly effective memorial was dismantled for want of money.

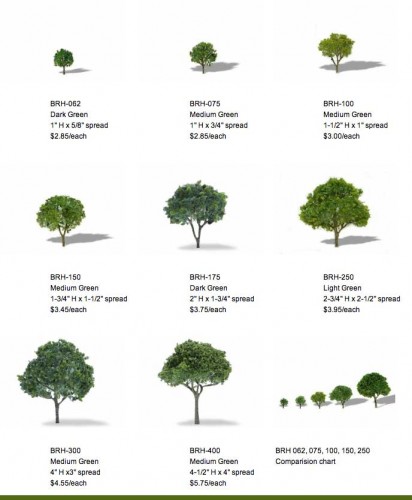

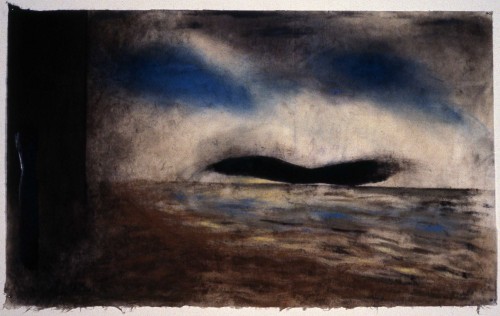

*Finally, my own memorial would have been really cheap. If I may be allowed a bit of fantasy, here is what for me remains a vivid image, as if it actually existed: at the very center of where the old complex had been, with the ground and the slurry wall left bare, would be a small replica of the towers made of precious metals and jewels, a Fabergé egg of the World Trade Center, as it were.

Souvenirs