I often say that I would like my paintings to have the density of a petrified walnut. That sounds ridiculous but what I mean by that is that within the small and also within the modest would be contained an intensity of materiality and of thought as dense as the molecular structure of petrified wood but at the same time with the explosive potential of the atom. I’m not saying I succeed. It is what I want.

What follows is a story (and the urgent advice to see two exhibitions closing soon, discussed here).

Years ago, when I was an undergraduate art history major at NYU, as part of a seminar about Albrecht Dürer, our professor, Isabel Hyman, took the small class to a Study Room at the Metropolitian Museum to see some Dürer prints. At that time Prints and Drawings were in separate study spaces. During our visit, a small box was brought out and opened–as I remember it, we were just standing around the person who brought it out–in my memory a person is holding an object being revealed to our small class as we cluster around. Layers of white cloth were peeled back to reveal something black and very old, about four hundred and seventy four years old at that time. It was an original wood block of one of Dürer ‘s wood-engravings. It was immensely precious because of that age and provenance and because we had been studying the artist’s prints in detail that semester. But my memory is so vivid of that moment of revelation because the block was very powerful in itself. As I thought of it in later years, it had the gravitational power of something like the black stele in 2001 A Space Odyssey that appears with all the possibility of civilization within it, but this object was all the more interesting to me because it was paper or tablet sized, not the enormous size of a work by Frank Stella or Richard Serra, but as strong a presence.

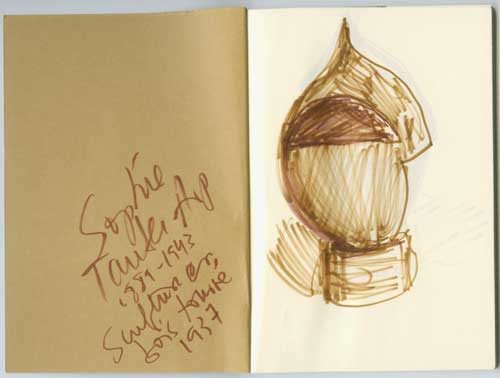

The half-life of that blackened piece of ancient wood in my mind has been long. As it happens, many of my paintings have been around the size of the object I remembered. It was a touchstone.

But I didn’t remember which print it was the woodblock for and it was such a long time ago, I began to wonder whether my memory was an invention.

Then a fortuitous circumstance arose: having learned that I’m an artist and a writer about art, my dental hygienist had often spoken to me with great pride about her daughter who was getting her PhD in art history, and who, parenthetically, knew who I was. One day she mentioned that her daughter was working at the Met in the Study Room for Drawings and Prints. I told her about my memory of the Dürer print, and that I had often wondered if I could ever see it again, to test the veracity of my memory and to recreate the experience. She interrupted her work on my gums first to text her daughter and then again when her daughter texted back to say yes, we have it, tell Mira to make an appointment.

As they say, only in New York.

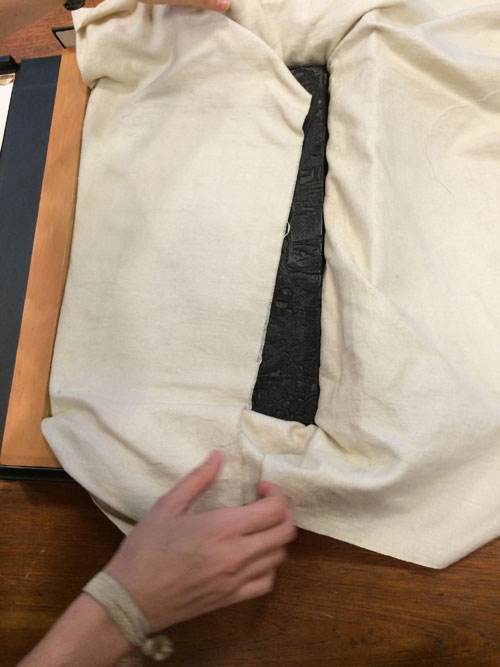

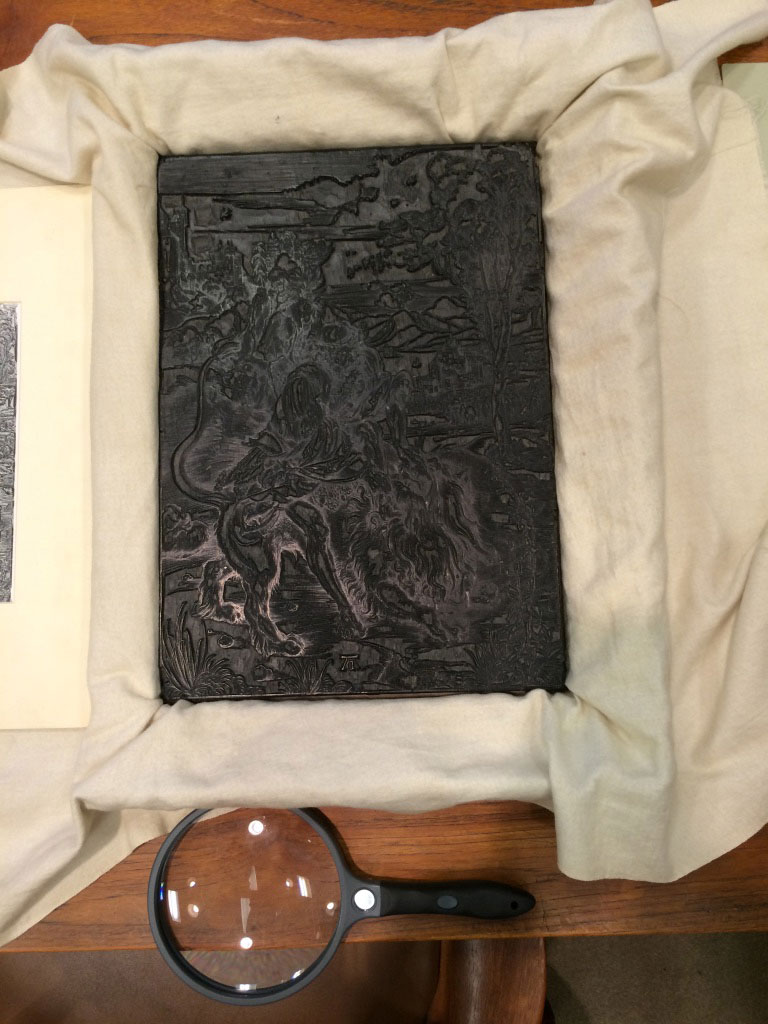

In February 2016, some forty-six years after my visit with Professor Hyman, I stood at a long table as a box was brought out and opened for me, a white flannel blanket unfolded and peeled back to reveal the first sliver of black and then the full surface of woodblock uncovered, a revelation as thrilling as the first time.

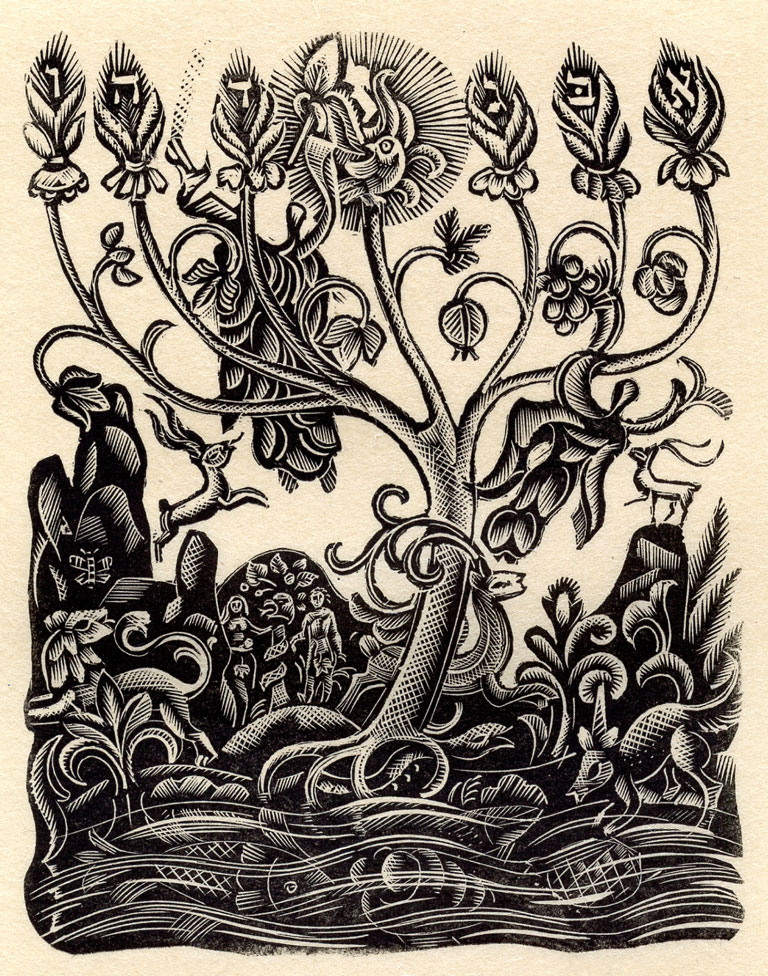

The block is of Samson Rending the Lion (ca. 1497-98).

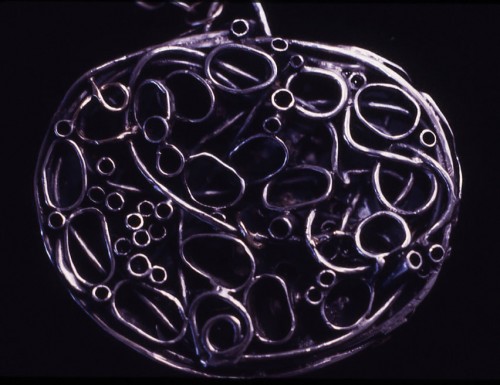

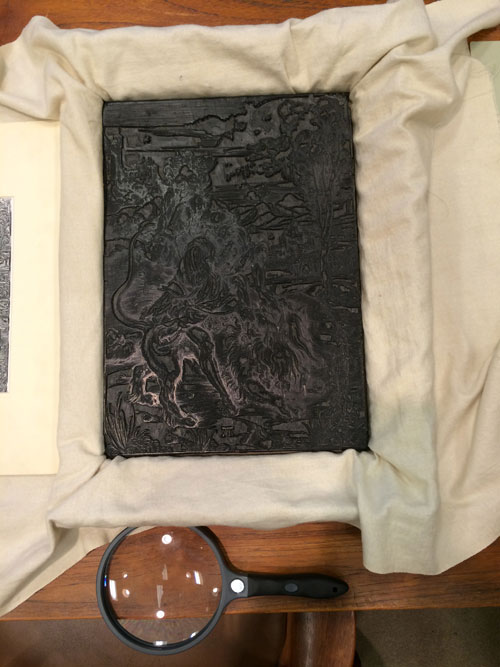

At first the thrill comes simply from its uncovering, then its presence, and that it is an object 500 years or so old and that it has been preserved. Then a scene begins to be decipherable, a tree, a cloud, a deep curved furrow into the wood.

It is remarkably sculptural, it is a thing.

Yet its depth is illusory on many counts Of course in relation to the impression on a flat piece of paper, it is dimensional, but it is a piece of wood whose depth one can only deduce from the depth of the box that contains it, and that isn’t that deep relative to the surface area. Maybe it is an inch deep, and if so, that it has survived at all, that it has survived hundreds of impressions and centuries of climatic vagaries of storage (I seem to remember that many of Dürer’s graphic works were found in a trunk) is incredible.

But then comes the act of magic that is an impression, the print that is an indexical trace of the block but in reverse. It is so complex to read the print against the block and see how these fine lines and deeper furrows become a lion, a blade of grass, a cloud, the cloud dug so deeply that a shore line is established, like a black cliff and, even more incredibly, how little marks, like barely raised letters of braille in a deeply carved out field become a fulsome beard or a flock of birds in the distance. The visual intelligence that goes into this magic trick of reversal from left to right and from negative to positive is incredible.

Everything I am saying has mostly to do with its objectness, nothing to do with the style of Dürer but that style is part of the magic trick, how the intricate delicate and angularity of the Gothic and the attention to intricate detail in nature characteristic of the Northern Renaissance intersects with the bolder more sculptural forms of Italian Renaissance painting.

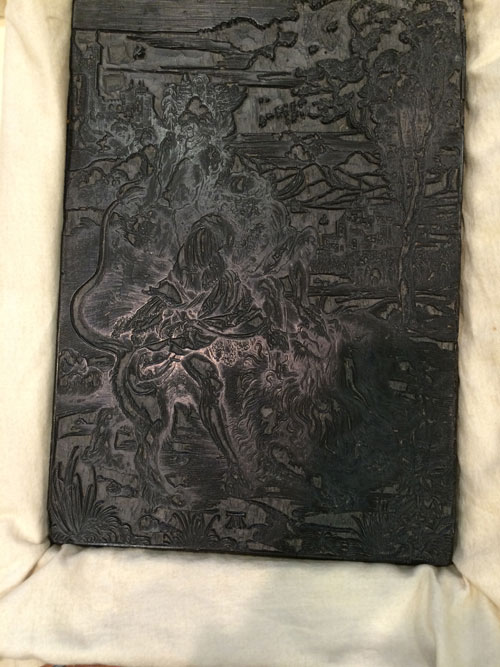

Now another box was brought out.

Dürer’s The Martyrdom of Saint Catherine (c.1498) in some ways is even more incredible as an engraving than Samson Rending the Lion because the composition of the scene is more complex, with more figures and a less centralized composition. You can examine the block in closeup detail here, though one of the problems with representing it photographically is that it is hard to get the sense of blackness that varies greatly depending on the angle of vision and the light. At first this block itself seems flatter, the fine lines of engraving that make up the line of the earth seem hardly there and also are more worn down by timely usage but then the deeper furrows that create the whitest whites of the print become even more surprising. Considering the subject–the gory martyrdom of St. Catherine of Alexandria–it is surprisingly easy to get distracted by the emphasis on fashion of the day and hard not to bring a contemporary eye to bear on the cute derriere of the executioner’s leggings and extravagant contrapposto yet at the same time, particularly in the wood, the stripes become like ligaments of an anatomical sculpture.

At the top of the block, the angry outburst from the sky of clouds, rain, and flames are engraved and even gouged deep into the wood with traces of the engraving and carving tools utterly visible.

Saint Catherine’s medieval intricacy creates more abstract areas of carving, and because the plane is flatter and picks up the light more it becomes more like a negative of the positive in an intellectual, procedural relation to photography, yet it is a plaque of wood, black like ebony.

Indeed a component of my memory is the misapprehension that the wood itself was black, not the product of hundreds and hundreds of inkings, including even some rumored to have been done by the Museum itself in the earliest years after its acquisition.

We can feel the hand of the engraver in action, the light hand and the strong hand, you see the deftness and the gouging. Here a bit of a historical mystery intercedes: it is not known for certain whether Dürer did the actual wood engraving or whether professional wood engravers did the work. He also made copper plate etchings and these are certainly by his hand. As to the woodblocks, one theory is that, operating in a strict guild system, Dürer would not have been allowed to do the actual wood-engraving. But on the other hand he owned his own studio as an independent business and there seems to be no doubt that he did do the work on some of the wood engravings. In his youth Dürer received training in engraving techniques from his father, a goldsmith. He was intent however that he wanted to study painting and was apprenticed to the painter Michael Wolgemut, where nevertheless he witnessed his master’s large workshop’s production of wood engraving illustrations. He later found that printmaking was an important part of his business as an artist, of what we could anachronistically term his artistic “practice.” The blocks themselves were an important financial resource and he fought, sometimes unsuccessfully, against counterfeiters to establish legitimate provenance. Thus the blocks themselves were important financial resources.

No matter whose hand realized Dürer’s drawing, a person did this, over 500 years ago. And the blocks hold that person’s trace in solid matter of which the print is a secondary trace.

The Metropolitan Museum acquired these two blocks as a kind of peripheral gift: the prints were sold to the Met in 1919 by Junius S. Morgan, J.P. Morgan’s son, and he gifted the the museum the blocks. One of the implication of this gift is that the blocks were not seen as having that much value–or was it that they were in a sense without price.

Most museums are only able to display a small percentage of their collections so it is interesting in itself to look behind the public scene at some these hidden treasures but this object, which I would have chosen, if by some chance I had ever been asked to do one of the artists’ choice video presentations the Met produced for a few years (discontinued by the museum shortly before I finally saw the Dürer blocks), although it has been on occasional display, is, strictly speaking, not an art object in itself, it is a transitional object, an instrumental object, of which the indexical trace is considered the art work. When it is shown, it is mainly for educational purposes to demonstrate how a positive print of a such a wood engraving is created.

But as it happens, the wood block of The Martyrdom of Saint Catherine is currently on view, through June 23, in “Relative Values,” a show that examines the economic value art and craft objects had in sixteenth century Europe, measured by how many man hours of work it would take to gain enough silver to buy one cow, and, from that basis, how much any particular art work or artifact is worth in cows. The bare bones industrial-style installation reveals the depth of the block: it is as thin as the depth of its box had suggested. How a piece of wood would last so long is much a miracle as the story of St. Catherine’s martyrdom, that when St. Catherine touched the machine that was to break her bones and kill her, it shattered.

The exhibition does not afford us the ability to compare the block to the print, because the pedagogic point of the exhibition is the relative value of works and objects in the Northern Renaissance, not the relation between matrix and indexical imprint although I am not sure why another Dürer print is exhibited instead. In fact I’ve seen Relative Values three times, and each time, while the woodblock of Saint Catherine remained on view, another print was displayed in a separate vitrine, a different one each time I went. Although the focus of the show is on the relative value of works in that time period, displaying the print of the block would illustrate the difference in value between block and print and be of double pedagogic value.

A Dürer or Dürer-related print was worth only one cow X 1/2. If the block was worth a value equivalent to the cost of a cow multiplied by 16, thus 35 days pay for a skilled craftsman working in London or Anthwerp multiplied by 16 or 85,600 loaves of bread in Brussels while a print of a posthumous portrait of Albrecht Dürer was worth a cow X 1/4, then how many cows or thousands of loaves of rye bread would one contemporaneous print from the Saint Catherine block be worth?

The Dürer works in this exhibit are discussed in an interview by Will Fenstermaker of curator Elizabeth Cleland. [The exhibition at the Met closes June 23rd so run if you want to see this amazing block for yourself]

*

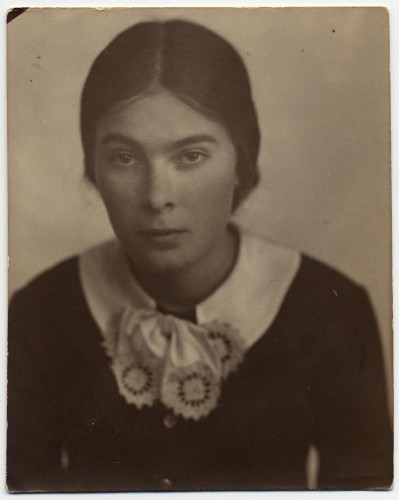

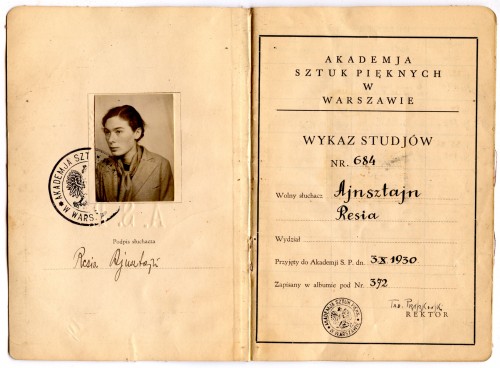

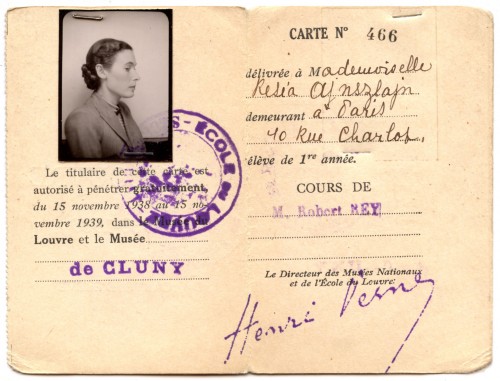

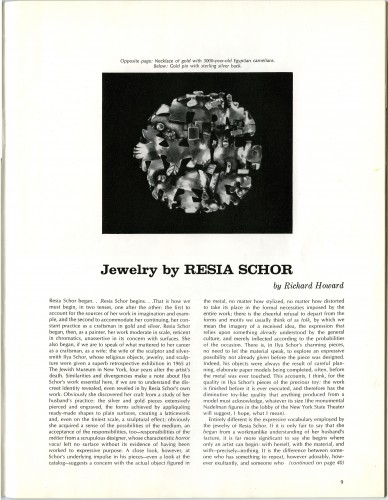

The tools that Dürer would have used had not changed much when my father Ilya Schor was apprenticed to a goldsmith / engraver in Eastern Europe about 440 years after Dürer first learned the craft of goldsmithing from his own father. My father, like Dürer so long before him, learned the goldsmithing craft before studying painting, and, also like Dürer, later turned to wood engraving and illustration of biblical themes as part of his livelihood.

I don’t think that when I first saw the Dürer block or when I was studying his wood engravings as a college student, I made a conscious connection between the impact of seeing that block of engraved wood and my memories of watching my father engrave on hard wood and print on rice paper.

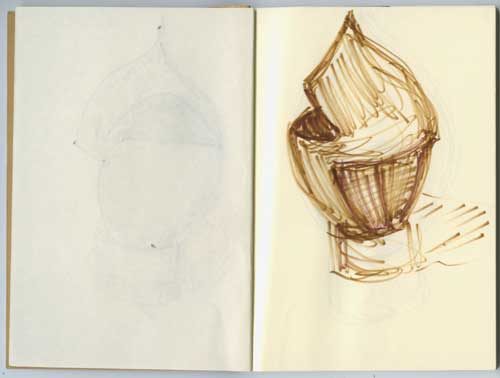

However, a few weeks before my visit to the Met, it happened that I sat at my studio table with the blocks for my father’s wood engraving illustrations for Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel’s The Sabbath laid out in front of me. They too are blackened by printing. Indeed I have a haptic childhood memory of the smell of the heavy black printing ink and the satisfying gooey slapping sound it made as my father rolled it out on glass before rolling it lightly and evenly onto the wood. I don’t picture the next part of the memory, the wonder of his pulling the print, but it was clearly ingrained, and to this day I find the miracle of drawing/engraving in reverse of the final image a mystery in the deepest sense, a ritual of complex thinking.

*

This spring I took a group of graduate students to see a special exhibition at the Renee and Chaim Gross Foundation. The exhibition “Teaching Through Touch: Works by Chaim Gross,” is aimed at allowing the visually impaired experience sculpture through touch. Young artists today are so immersed in the tiny images of art they see on Instagram that many important components aspects of the real, including scale, surface, mass, and weight are not part of their embodied experience of art, a lack which affects the kind of art they are able to imagine making. They loved the exhibition. (This special exhibition runs through June 30.)

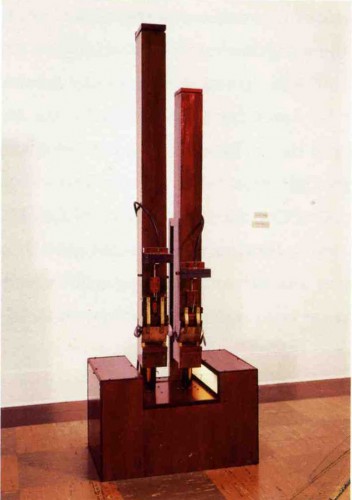

At the end of the visit, the museum guide lifted a small sculpture set on a table and asked us each in turn to extend our arms and prepare to stand firm: she then placed the object in each of our cradled arms, one at a time, and, boom, the thing weighed a ton! The work, entitled Pumpkin, from 1933, is sculpted from one of the densest woods on the planet, Lignum Vitae. On the Janka scale of hardness, Lignum Vitae has a density measured as 4,390lbf while Pearwood’s density is 3,680 lbf –which is pretty dense–for reference, baseball bats are mostly made from Ash which has a hardness of 1,320 lbf (denser woods being deemed too heavy to swing).

Perhaps then Dürer’s woodblocks do partially owe their survival to their relative density despite their relative shallowness. But then the blackness, the age, the hand of the artist and the image trapped within it imbue it with the mythic density that struck me when I first saw it.

Relative Values: The Cost of the work of Art in the Northern Renaissance runs through June 23 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, it’s on the main floor in the back near The Robert Lehman Collection and “Teaching Through Touch: Works by Chaim Gross,” runs through June 30 (call for appointments)