The first issue of M/E/A/N/I/N/G: A Journal of Contemporary Art Issues, was published in December 1986. M/E/A/N/I/N/G is a collaboration between two artists, Susan Bee and Mira Schor, both painters with expanded interests in writing and politics, and an extended community of artists, art critics, historians, theorists, and poets, whom we sought to engage in discourse and to give a voice to.

For our 30th anniversary and final issue, we have asked some long-time contributors and some new friends to create images and write about where they place meaning today. As ever, we have encouraged artists and writers to feel free to speak to the concerns that have the most meaning to them right now.

Every other day from December 5 until we are done, a grouping of contributions will appear on A Year of Positive Thinking. We invite you to live through this time with all of us in a spirit of impromptu improvisation and passionate care for our futures.

Susan Bee and Mira Schor

*

Matthew Weinstein: American Dreamers, 2016, on the Precipice

Americans are dreamers. For us, the line between fact and fiction is one drawn in the sand. I can’t condemn this, as it goes hand in hand with our ability to create contemporary culture.

What has happened to our dreams?

Our dreams have been eaten up by a distraction-heavy media. Our imaginations are no longer the stars of our fictive universes, because they have been occupied by nonsense.

Celebrities. What they think. Who the fuck cares what they think? Cute endangered animals. They aren’t our fucking friends.

Celebrities getting the Congressional Medal Of Freedom. How about a school teacher. A nurse. How about an unsung activist? How about a damned struggling artist? How about attainability? No wonder most of the country thinks it’s all rigged. We don’t honor the nameless. We should. Not that anybody with an ant-sized amount of brains, or conscience, would accept an Iron Cross from the Nazi Elect.

For all the good that has happened in the last eight years, there has been an above average level of stupid.

High/low distinctions are idiotic. But useful and useless distinctions aren’t.

We have become mired in horizontal thinking. The Huffington Post tracking an actor’s political views, Trump, and an amazing cat that will amaze you, have become equally vital news. And this is linked directly to people blind to the radical horror of a Trump presidency. It is not all the fucking same.

Why does the left always think that revolutions are for us? Because we think and forget to see. Art is about both of these things: thinking and seeing. It can sort of help.

Our art world is mired in auction results, gigantism, art fairs as the places to see art rather than galleries and museums, and online art gossip sites with cute names. There is nothing inherently bad in any of these things. Got to make the donuts. But the problem is that we read them, and about them, when we should be connecting to what actually matters; art, politics, sex, napping, eating the wrong foods, quality nonsense and each other.

If you want to say that artists are just another form of entertainer, say it. But you’re wrong. We aren’t superior. But we offer something else; an alternative to mass experience, when we are doing our job. Just more mass experience when we are sucking up.

A work of art that opens up your mind and or heart, pisses you off, makes you actually laugh, makes you deliciously sour, makes you want to rush to your own studio, or makes you want to grab a friend and talk about it; these things are not protected. Art is as fragile as Democracy. Fight for it. It won’t take care of itself. We are responsible to protect it. Not museums; us.

Art needs to present a safe haven for the personal, the specific, the unpopular and for people who care about unjustifiable things; a safe haven for us to talk about art as if it matters deeply. Because it does. And criticality matters now more than ever. We are forgetting how to do it. It’s too often scorned. Which leads to art feeling like propaganda for art.

Anyone who uses the word ‘hater’ needs to put a dollar in my mistake box. I’ll buy cool stuff with it. Be a critical asshole. Lot’s of things completely suck. I mean within reason.

I love art. Always have. I’ll never go negative on the art world because it’s my brain home, and because it is always and has always been raw potential. Which is why I get upset when I see it squandered.

In this time, as artists, all of our opportunities and impulses have to be treated as if they are our last ones. We need to do and say exactly what we mean, without apology or fear. We may not know how to fix things, but we can demonstrate what urgency looks like.

Keep the dreams flowing. But let’s make sure that they are our own. Respect the animals. They are us.

Matthew Weinstein is an artist who lives in Brooklyn NY. He also writes for ARTnews and Artforum.

*

Jennifer Bartlett

![Jennifer Bartlett, A few days after the election a pop-up artist/therapy piece began growing in the Union Square subway station. Passersby were encouraged to write a message to the world [in response to the election] on a "sticky note."](https://ayearofpositivethinking.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Jennifer-Bartlett_Image_One.jpg)

A few days after the election a pop-up artist/therapy piece began growing in the Union Square subway station. Passersby were encouraged to write a message to the world [in response to the election] on a “sticky note.”

My note says: “I am not retarded.” I have cerebral palsy, and I was frustrated that I could not get to a flat surface to write on. Ultimately, this became part of the effect because the writing “looks retarded,” i.e. what Donald Trump and most abled people would construe as “retarded” or distasteful or stupid. The message was directly based on the fact that the US elected a man who called a Deaf actress “retarded” and coined the term “libtard.” In reaction to Trump mocking a disabled reporter, in the way I have been mocked continuously throughout my life, Ann Coulter attested that he was just making fun of “general retards.” Virtually no one responded in protest, and as Trump moves toward the White House, there is still no protesting of able-bodied people in defense of disabled people. That is the one line people won’t cross. So be it.

Jennifer Bartlett is a poet, occasional writer for the New York Times, and working on a biography of Larry Eigner.

*

Ann McCoy

Our country is in turmoil, and tomorrow seems uncertain. In this Saturnian winter, as we wait for the solstice and return of the light, it is ever harder to gather one’s resources—keep one’s spirit intact. During these months our ancestors lived indoors, huddled around fires. We have no such kinship and are disoriented by electric illumination and central heating. Experiencing the darkness seems harder without nature as our guide. During a winter much like this one in Berlin, I remember walking through the snow to a small Cranach museum on a lake in the middle of a forest. An advent wreath in a window led the way to a nativity scene by the Elder. I was moved to tears by the Bethlehem scene tucked in this dark hunting lodge. Today I lit my advent wreath, hoping for a similar miracle, a light bringer, a candle in the darkness. In my neighborhood a group of Coptic brothers and sisters invited me to their morning prayers. Most of them are from upper Egypt and are from the same village as the twenty men who were decapitated by ISIS in Libya. I am honored they have invited me, the singing in Coptic is transporting. I am grateful to have a place around their fire, as I light a beeswax candle in front of the Theotokos. Their optimism, charity, and kindness touch me deeply.

Ann McCoy, “Lunar Birth” with the artist, 2001. Pencil on paper on canvas, 9 by 14 ft.

Ann McCoy, “Processional with Lightbringer,” 2005. Cast bronze with silver crown, 19 in. by 7 ft. 2 in.

Ann McCoy is a New York-based sculptor and painter whose career began in 1972. She is a working artist as well as a curator and art critic who writes for the Brooklyn Rail. She lectures on art history, the history of projection, and mythology in the graduate design section of the Yale School of Drama. McCoy is a winner of the Prix de Rome, the D.A.A.D. Kunstler Award, and American Award in the Arts.

*

Mimi Gross

On the election

Shadow of shadows

Caught, cut, & painted (black)

Present and future disasters

Goya could.

We are leaping into an abyss

Black air

Somehow, mid-air, breathless truth,

Calls out: the Arts will conquer!

Which

Blue sky

Is brighter

Than the sun itself

Or is it

A late moon?

We will challenge the falling columns.

*

30 years, Forums on:

Meaning: combining amazing and absurd. So many dreams broken, glued together

overhauled. Now a new generation will share the wide spectrum of “Meaning.”

Motherhood and art: Bathed in love. My daughter is long married and has two

wonderful daughters, now 17 and 13. Difficult to have imagined 30 years ago. The juggling of time before, has

become a privilege, without sharing responsibilities.

Racism: Confusion within the sphere of art matters. The attention to African

American and of mixed ethnicity artists is totally exciting. (A much longer

response is needed to recognize and discuss the great from the trendy.)

Highly recommend: the Kerry James Marshall exhibition at the Met Breuer.

Feminism: Will we be in danger of disappearing? I don’t think so. The younger

women artists (in all fields) have no concept of the difficulties

encountered by the invisible generations before them.

Resistance: This is our strongest positive hope.

“On art making over a lifetime, from youth to older age:”

(76!) What is Real?

Find forms,

Listen to history,

See more.

Time:

Wood, plastic, paint,

Cardboard, band saw, blades,

Hot glue.

Still:

Scaled for future details,

Depth, present, murky,

Let go!

Unlimited perspectives,

Counterpoint concepts,

(disparate images)

careful creation:

artifice

make a detail,

blow it up,

Let the scale go,

Without forgetting it

For a second.

Drawing all along the way.

Study by means of doing.

(Diaphanous)

A line,

A shape,

To do

The idea

Brightness of space, of light:

Integrate the white line,

Marry the line with paint.

Imposing, Or, vertical lines

Serious, Layers of thoughts

Things past Catching quickly,

Remember. Time passing.

Find personal (line).

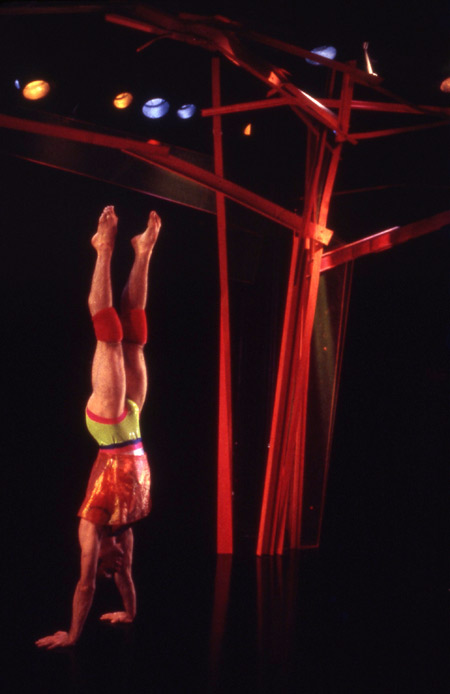

Mimi Gross, design collaboration with Douglas Dunn: “Aerobia,” Choreography Douglas Dunn, 2001

Dance/ Collaboration, sets and costumes:

To fly: is it Dance?

Disjointed together

Chaos in place

Literal becomes abstract

Abstract becomes literal

Speed of images

Capture. Drawn out

Put together

The silhouette is

The darkest weight

Hear the dance.

Travel

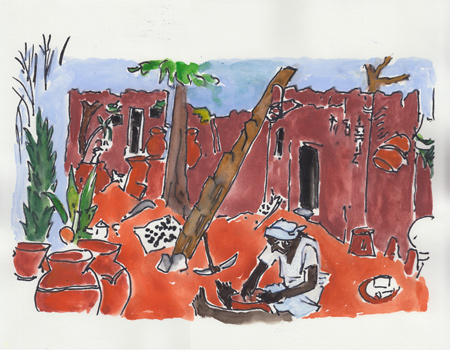

Travel experiences transform, broaden perspectives, escape from “provincialism,”

accumulate new ideas.

Portraits become landscapes, landscapes become metaphors,

Psychology of place, of scale, of texture, of color.

(direct fun)

(breaking all the rules)

A form of sanity.

Mimi Gross, “Village outside of Gaoua, Ivory Coast, West Africa,” 2013, watercolor and ink.

Mimi Gross, “Mercado Sonora, Mexico City,” 2012. Watercolor and ink in sketchbook.

Mimi Gross is a painter, set and costume designer, teacher, who lives and works in NYC. Recent group shows include: Brooklyn Museum of Art: “Stephen Powers, Coney Island is Still Dreamland”, 2016; Brattleboro Museum of Art, VT, “After Old Masters”, 2016. AMP Gallery, Provincetown, MA, 2016. In 2017, her mural for the University of Kentucky, Medical School, Louisville, will be installed; her work will be in a three-person exhibit at Derek Eller Gallery, NYC, and in a large group exhibit at Grey Gallery, NYU, “Inventing Downtown: Artist-Run Galleries in New York City, 1952-1965”, Jan.-April, 2017; she will have an “Art Project” in Art Journal, spring 2017. Mimi has worked with Douglas Dunn and Dancers since 1979, designing sets and costumes for over 25 different dances, including Antipodes at St. Mark’s Church, NYC, ” Feb 2, 3, 4, 2017.

*

Myrel Chernick

Some questions I ask myself:

What does it mean to live an ethical life?

Does a creative life imply an ethical life?

Can I make art that is substantive, relevant, and meaningful, that makes a worthwhile contribution to the lives of others? And what does that entail?

What is my responsibility to those who have so much less than I do?

The problems seem insurmountable: poverty, climate disaster, bigotry, misogyny, xenophobia, homophobia, unmitigated greed. What is the best and most effective way to move forward?

I first encountered M/E/A/N/I/N/G with #12, Forum: on Motherhood, Art and Apple Pie (1992). There I learned that my difficulties with the art world that had increased after I decided to have children were by no means unique, and my subsequent exploration of maternal ambivalence became a group exhibition and then a book. Twenty-five years later, I know of no other American art periodical with an issue devoted to this topic. Thanks to Susan and Mira for their pioneering work on so many topics.

Myrel Chernick is an artist and writer who lives in New York.

*

Robin Mitchell

M/E/A/N/I/N/G has put forth questions of and about meaning in art for 30 years.

Meaning in art and culture has not changed in those years, but what has changed is how art has meaning. Critical thinking is propelling art rather than art generating critical thought.

When I was in school I was often confronted by the question “What does your art mean?” I have continually asked myself, “What does my art mean?” “What does it mean to me?” “What can it mean to others, other artists in an insular world, or to others in the wider culture and beyond?”

My experience as an artist has deep personal meaning. After a lifetime of artmaking, I feel that I making the best work that I have done and for me art making is a rich and rewarding process. I understand my artwork better and more completely as I continue making art. Artmaking for me has become personal reflective process, more of a world inward, and I find the richness of this experience deeply rewarding and gratifying. By exhibiting my artwork I am part of a dialogue with other artists and the larger art community. I would never expect for everyone or even many to make a connection to my work. What others find meaningful may be different than the meaning I intend. Yet when I exhibit the work, I am humbled by the connection that some people communicate to me that they can make to the artwork. This connection so often mirrors my own intentions.

I want to be counted for my stand and my beliefs. In light of the recent election I feel this even more vehemently. The act of being an artist is in some ways an act of defiance. I want my concerns and beliefs to be counted in the world, whether through my art or my actions. Marshall McLuhan said that he looked to artists to see where the rest of the culture was moving towards. “Art at its most significant is a distant early warning system that can always be relied on to tell the old culture what is beginning to happen.”

Robin Mitchell, “Numinous,” 2016. Gouache on paper, 24” x 18”

Robin Mitchell is an artist living and working in Santa Monica, California. Her paintings are represented by the Craig Krull Gallery also in Santa Monica. Her artwork has been recognized by a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, the Anonymous Was a Woman award, a City of Los Angeles grant, and a California Community Foundation mid-career fellowship. She holds a BFA and MFA from Cal Arts. While a participant of the Feminist Art Program at Cal Arts she was part of the historic Womanhouse project.

Judith Linhares

I am writing my account of what it is to be an artist and a feminist in very transitory times, not even two weeks after the election of Donald Trump. I do not know what the future holds what I do know is I have had a lifetime of political involvement. I would characterize that involvement as recognizing that other woman are struggling with finding their own agency struggling with the various rolls and fantasies placed on them by the dominant culture and like all of you I am looking for a way forward at a time when racism and misogyny are returning to the White House.

I believe my fate is connected to the circumstances of all other women. I have more energy and confidence when supported by others. I have been involved in feminist politics for a long time I owe a lot to the recognition and support of other woman I believe we share common cause. I have great respect for Mira Schor and Susan Bee for their decades long project M/E/A/N/I/N/G. This project has given legitimacy to woman’s ideas and opinions over the decades I am proud to be included in this valuable document.

I do not see clearly as yet what future challenges will look like. My plan is to keep working and try to see the truth as I experience it day by day. My hope is that I have the courage to speak out in opposition to injustice when I see it.

Judith Linhares, “Back Talk,” 2012. Gouache on paper, 29.5 x 44.25 inches

Judith Linhares’ paintings have been the subject of 40 one-person exhibitions. Her solo shows at the Edward Thorp Gallery, as well as a survey, “Dangerous Pleasures: 1973-1993,” received numerous reviews. Marcia Tucker’s inclusion of her paintings in “Bad Painting” and the Venice Biennale encouraged this fourth-generation Californian to ride the New Figuration wave to New York City. She has received many prestigious awards and was honored by the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

***

Further installments of M/E/A/N/I/N/G: The Final Issue on A Year of Positive Thinking will appear here every other day. Contributors will include Alexandria Smith, Altoon Sultan, Aziz+Cucher, Aviva Rahmani, Erica Hunt, Felix Bernstein and Gabe Rubin, Hermine Ford, Jenny Perlin, Joy Garnett and Bill Jones, Joyce Kozloff, Julie Harrison, Kat Griefen, Legacy Russell, LigoranoReeese, Mary Garrard, Michelle Jaffé, Nancy K. Miller, Noah Dillon, Noah Fischer, LigoranoReese, Robert C. Morgan, Roger Denson, Tamara Gonzalez and Chris Martin, Susan Bee, Mira Schor, and more. If you are interested in this series and don’t want to miss any of it, please subscribe to A Year of Positive Thinking during this period, by clicking on subscribe at the upper right of the blog online, making sure to verify your email when prompted.

M/E/A/N/I/N/G: A History

We published 20 print issues biannually over ten years from 1986-1996. In 2000, M/E/A/N/I/N/G: An Anthology of Artists’ Writings, Theory, and Criticism was published by Duke University Press. In 2002 we began to publish M/E/A/N/I/N/G Online and have published six online issues. Issue #6 is a link to the digital reissue of all of the original twenty hard copy issues of the journal. The M/E/A/N/I/N/G archive from 1986 to 2002 is in the collection of the Beinecke Library at Yale University.