Did you know that Saint Precaria has been determined to be the patron saint of adjunct faculty?

A judicious amount of research (one Google search) makes it reasonably clear that there is no such person, this is a fictional creation, presumably the sister of “San Precario,” a fictive patron saint of precarious workers invented in Italy in 2004. The “precariat” now includes many who formerly would have been considered privileged members of society, the educated and the educators, categories which now include students burdened by debt and their adjunct faculty of all ages. Students pay exorbitant costs to participate in a system where a larger proportion of their faculty may be members of the precariat, part time adjunct faculty, many of whom once were students in the system themselves and in many cases are living proof that student debt cannot be paid back on adjunct wages.

February 25 was National Adjunct Walkout Day. As a member of ACT-UAW, a union of part-time and adjunct faculty at The New School and NYU, I was contractually unable to participate–and in fact I don’t teach on Wednesdays so there was no class to walkout of, or to conduct a teach-in during–but it was a useful opportunity to mark the plight of Adjunct faculty in higher education.

What a Victorian term I have used–plight, “a dangerous, difficult, or otherwise unfortunate situation” according to the definition that springs up on a Google search. Dangerous, yes, that is the operative word–it is dangerous not to make a living wage, and here I want to stress that a wage is different than a living wage, and dangerous again when you realize that wages are reflected back at you later in life in Social Security benefits which are based on taxable wage income. I realized the other day that my anticipated benefits, even if I wait the longest possible to receive these benefits (should SS still exist at that time), will be lower than what I currently pay for art storage. Not a cheery prospect.

In recent months I have been tempted to reveal this “plight” more fully, on the chance that whatever prestige I may have, whatever respect in which I may be held by some would give some weight to my experience of the financial as well as other institutional realities of part time faculty. But why would I worry about that and cling to my resume for protection against Darwinian staffing practices? Because in America, and probably everywhere, it is always easier to believe that someone’s fate is their fault. This is of course a deep philosophical argument but you always have to think about what power wants versus what might be valuable in other ways. We love the myths about geniuses who died penniless but in the present tense we despise someone who ended up making choices that were financially unwise even if the reasons and even some of the outcomes were important contributions to the culture. Someone actually suggested to me a while back that I was in my own way the cause of the crisis of the adjunct and of my own problems at that particular moment–*as a threat to the tenure system* (the speaker was tenured)–because I had accepted adjunct positions in the first place! Thus my precarious position, as well as the threat posed to the tenure system(!) by management’s exploitation of adjuncts, was my fault.

And, further, I assume that from the point of the administration, a person’s willingness to be paid a below poverty wage is a demonstration of their worth, or rather their worthlessness. If you are stupid enough to accept low wages, you must not be worth more anyway. It’s one of the reasons one rechecks one’s resume on occasion, to be reminded of proof to the contrary.

Of course personal back stories abound, some details of my situation certainly are the result of my own decisions and my preference for staying in New York–I could in fact right now be retiring from my first job, a full time teaching position at NSCAD, where I was at 24 the only woman in a 14 man department–but other scenarios have to be understood or imagined: a feminist walks into a room full of men wearing tight jeans and cowboy boots interviewing her for a job and… — a feminist seen as “essentialist” walks into a room of students empowered to influence hiring decisions and…the university loses a tenured line because of…..Also I must add that for a long time the adjunct situation worked for me: for various reasons which unfortunately no longer pertain I could get by, for quite a long time I enjoyed agency as a teacher, I was able to work on projects which I might not have been able to do if I had a full-time position. I was not as aware of the precarity of my situation as I perhaps should have been because things seemed to go along as they always had. Perhaps some understood years ahead the direction that the economy and working conditions would take, but I was not one of them. My mother had a clearer view: once, when she was in her nineties, she turned to me from a story on the news and said, “so, in America soon it will be the corporations and the slaves.” That was in around 2005, when a lot of things began to change, certainly at the level of my experience of academic politics and employment.

In recent years, it is clear that things have changed, in education and in the economy, and so now this is the way that the current economy works, all blame and shame falls back upon the individual, the meaning of “the personal is the political” has reverted back solely to the personal, the individual and all efforts to break out of the isolation of the individual are the target of national, state, and corporate power, to crush workers and particularly unions. The flaw in pridefully resorting to my own accomplishments as proof that I should be exempt from such difficulties because of whatever I think is special about me is that all faculty who work as adjuncts have their own story of accomplishment. Most of the people I know who teach as adjuncts are experienced and dedicated teachers, particularly given the short remuneration. Beyond that, by resorting to claims of one’s own uniqueness, one loses a sense of solidarity with others, and that is of course exactly what the power structure wants.

Another reason to hide the details of one’s employment are not just the fear of retaliation from the institution–an issue covered in “The Teaching Class,” an interesting article by Rachel Reiderer–but of the resentment of full time faculty: adjuncts after all don’t have to do often soul numbing service to the university. It should be noted that the work load and corporate pressures on full-time faculty have increased as the administrative wing of universities is increasingly impinging on the educational, although an early reader of this blog post noted a situation of indentured servitude I had not imagined, where tenured faculty were increasingly using adjuncts to do the administrative work, for paltry additional sums, so that they could concentrate on their own work and research. He even suggested, in jest but with purpose, that soon the adjunct system would be replaced by the model of the unpaid intern, with a tenuous promise of perhaps ascending eventually to adjuncthood! Whatever the situation of full-time faculty, the work load and extra-curricular demands on adjuncts has also increased in recent years. Last year I put in 40 hours of extra unpaid work–basically a full semester of work hours extra–since I was at my computer I could mark the time very exactly–in order to insure that the “product” of my students in one class would be adequate. I did so partly out of a sense of duty and perfectionism that is just habit, but also because there is always the fear that you will suffer if the student “learning outcome,” the educational product is deficient. Whether that fear is justified or not is irrelevant to the general atmosphere of a student-as-consumer educational system where an individual student’s complaint can be a very useful tool to displace part-time faculty.

Another anecdote springs to mind, from a period in the recent history of my institution when the full time faculty were in full revolt against the President for blurring the lines between/privileging business over educational elements of the administration of the university while all hell was breaking loose in other departments, all of this well-documented in the New York Times and a dozen other major news hard copy and online magazines at the time. At that time I wrote to a full time faculty member on the Faculty Senate “I think that the Faculty Senate must support the part-time faculty in the Fine Arts Department. This is not just a matter of fairness and compassion for colleagues during an economic depression, or just a Union matter, what is at issue is the inexorable enactment of a totalitarian take-over of a major area of study by a business oriented point of view. ” His reply was basically, “must we?.” He resorted to rules of order of the Faculty Senate, bla bla..and this from a Marxist, naturlich.

On the other side, one worries about the possible loss of face in relation to students who respect power and fear a less than rosy intimation of their own future. But as faculty today, teaching in a private institution, one is torn between a mystery and a sad reality. The mystery is that one does not always know which students are rich enough through family wealth to weather the direction of the economy and support their art practice when they leave school. The sad reality is that this is increasingly an economy trending towards work for no pay: unpaid internships, publication for no wages, graduate students and adjuncts carrying the teaching load instead of tenured faculty, the examples abound. Since my area of teaching is art, there too appearances are deceptive, since anyone in the know knows that most artists don’t live from sales of their work, that most of the young artists one reads about who do have flash successes may quite rapidly find themselves devalued and out of favor. And a whole other text would have to be devoted to efforts to create new systems of education than the current MFA, but a typical example is one that I read just this morning, Andrew Berardini’s “How To Start an Art School.” Berardini notes the failure of the current MFA/debt model, praises some alternatives, and speaks with fondness of some models of free education: “For the past six years, I’ve been teaching at the Mountain School of Arts, an artist-run school based in Los Angeles. All the faculty, staff, and lecturers, including myself, work for free, and none of the students pay to attend.” This again is part of the sad reality part of the situation: there may well be tremendous pedagogic freedom in such models of free education, but unfortunately most people have to deal with one of the mysteries of life–how to pay the rent.

I admire adjunct faculty who are beginning to spell out the details. Last spring I was particularly impressed by a Facebook post by artist and activist Caroline Woolard, who broke down where the tuition dollars for a course she co-taught at Parsons the New School for Design (my employer) went. Woolard wrote,

I got paid $1854 to teach half of a 15 week course. It cost each student $4,155. With 16 students, the New School made $66,480 for the course, or $64,626, after they paid me. If each student gave me $14.60 a class, they’d have paid my teaching fee. Instead, they each gave the New School $277 for each class. Of course, the New School must pay their landlord, and their staff, but taking 95% ($277 vs. $14.60) per student per class is unjust. https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=567431575700&set=a.514378734020.2016859.28901120&type=1

(Price per credit: $1,385) x (3 or 4 credits per course) x (number of students) … so ($1,385 x 4 credit course) costs each student $5,540. Then there are 18 students, so the New School made $99,720 before paying me. Subtract my fee, and divide that number by the number of classes (15), and you get $370 profit per student per course.

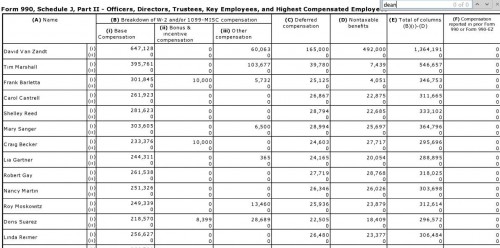

Next Woolard posted a number of jpegs, of the cost of various degrees at the institution and more significantly the annual compensation of the top academic and administrative officers in the university, information she found available online.

The issue of administrative salaries and the corporatization of universities was a topic discussed at The Artist as Debtor Conference at Cooper Union last month, though at that conference the ironies of having the difficulties of adjunct faculty explained very clearly by someone who herself had fired twelve of them in one day were particularly pungent.

The role that administrative salaries and structures have played in the corporatization of higher education is the subject of a number of books, including Benjamin Ginsberg’s The Fall of the Faculty and I highly recommend Bill Reading’s 1996 book The University in Ruins, which focuses less on the economy of the new university than on the rhetoric used to transform education into product.

The College Art Association guidelines for part-time faculty are interesting in all that they specify about advisable employment practices and all that they leave out, most notably the right to be paid a living wage.

On Wednesday February 25, National Adjunct Walkout Day, I had planned to write a long post about my experience as an adjunct but instead I napped for two hours in the afternoon because on Tuesdays this semester I have a challenging schedule that takes its toll. Remembering the one year in the late 1980s when I taught in three schools in three states, anything in one city should be a piece of cake, but I was younger and hardier then, and my lower overhead made the gap between wage income and living wage smaller. So just one more anecdote: ten years after my 3 schools, 3 states year, I told one of my Parsons grad students, after she had graduated, that my salary for teaching 3 and 3, then the teaching load of a full time position in most schools, was lower than her annual tuition. Her jaw dropped.

A more recent anecdote: this fall I asked one of my former students, a newly minted MFA, how much he was being paid for a course at my institution mainly to be sure he was being paid as fairly as possible, but when his wage turned out to be only about $7 less per hour or session or whatever it is that is the unit of our contracts than mine, with my 25 years at the institution and 40 years teaching experience, my jaw didn’t so much drop as my desire to break someone else’s flamed.

And finally, since ultimately the politesse of academia is just a tweed suit worn over an economy whose profile is total, here is a recent story on WNYC, where the CEO of Comcast meets with union employees in Canarsie, what happens when the gloves come off.

It used to be the economy, stupid but now it’s the austerity, stupid.

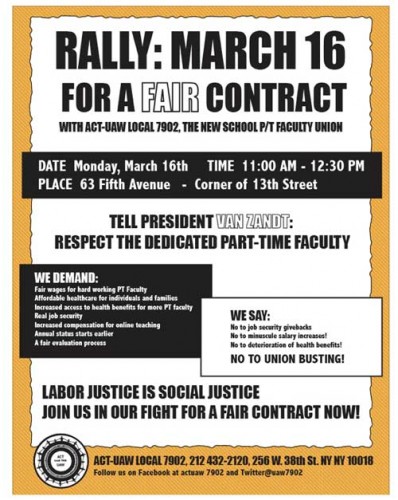

*Please join us for the Act-UAW Local 7902, The New School Part Time Faculty Union Rally!

This blog post was inspired by my union’s current negotiations for a new contract. Faculty “disqualification,” dramatic reduction of health care benefits and of already tiny salary increases are among the major issues on the table, while a new “signature” building was recently erected at enormous expense while problematic enough to inspire many faculty and staff critiques in submissions to an exhibition at the school, “Offense and Dissent.”