Free speech seems to be the latest thing, but in a strangely nostalgic way. This coming Saturday alone in New York City there are at least two events which will feature readings out loud from historical and contemporary political texts. Unfortunately I can’t be in two places at the same time so I won’t be able to attend “‘A riot is the language of the unheard’: an exercise in unrestrained speech” at The Rose Auditorium of Cooper Union at 4PM but wish I could. The event announcement includes this description:

Taking its cue from a quote from a 1968 speech about injustice and freedom by Dr. Martin Luther King, this public event engages in the use of the voice in imagining collective and political speech through short readings by artists, scholars, writers, poets, musicians, and speakers.

The event features a variety of contemporary and historic material such as re-performed texts, poetry, experimental theater, pedagogic exercises, as well as everyday collections of testimonials, essays, and private ruminations.

Envisioned as a “rough cut” anthology of live subversive speech acts, “A riot is the language of the unheard” is an experimental tribute to parrhesia, or defiant and confrontational speech. As surveillance and force is becoming increasingly utilized to control and manage resistance, this program seeks to address how the right to speak is also a politics of listening.

Later that day, from 6 to 8 I will be among a few artists invited to read at the closing event for an exhibition organized by some of my MFA students at Parsons, “Question for Revolution and Universal Brotherhood” where performances have included other public readings of political texts with an emphasis on utopian possibilities, some from the past but all for the current era. Invited participants at the closing events will also include Maureen Connor, Andrea Geyer, Heather Love, John T. McGrath, and Alex Segade.

Last week saw an iteration of the Free University in New York City, first initiated last May 1, with seminars taking place in the open air at Madison Square Park over a four day period, an Occupy-related event for once unmolested by the NYPD. Discussion included topics such as “What is Money – What is Debt” led by Sue Waters, “The Sirens and Subjection: Homer, Kakfa, and Adorno” led by Julie Napolin, “Letters to a Young Artist: What should young artists know?” led by Caroline Woolard (which was planning to begin with a reading and discussion on Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet), and “Discussion of The Alienated Librarian” led by Chris Alen Sula (a discussion inititated with students from Pratt Institute’s School of Information & Library Science of Marcia Nauratil’s 1989 book “The Alienated Librarian,” which examines the work of librarians from a labor perspective. (for the full schedule of events that took place September 18-22, click on the Five Day Schedule link on this Free University Page and for more photos from the event you can look at their Flickr page).

Inspired by the idea of the Free University, on Sunday October 14, I will lead a similar type of reading of Bill Readings’ predictive 1997 book The University in Ruins at Momenta Art as part of the current exhibition Occupy Your BFF, an exchange of ideas with Occupy Wall Street, with the involvement of Occupy related groups including the Arts&Labor group. Institutions including Parsons The New School of Design and the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts are hosting some of the events listed on this schedule.

This ferment, in the case of these examples mentioned above, has centered around education within and beyond the confines of the university and in many instances focused on political texts from earlier moments of political fervor, conflict, and engagement is part of a world wide growing movement of radical critique of post-War neo-liberalism and the ravages of global, unregulated super capitalism. In the US the increase in such activity seems to be framed by the crash of the 2008 economy and the upcoming election, although some within the Occupy Movement are so convinced of the evil of the two lesser of two evils argument of our electoral choices that they are rejecting participation in the vote.

While many media voices declare that Occupy is dead or has failed, discussion about the political and economic situation and how to affect it positively, continues, large or small, public events such as the ones at educational institutions or on web-based projects such as Nicholas Mirzoeff’s year long daily blog Occupy 2012 or in small ongoing private discussion groups, the large meetings inspirational and occasionally dramatic (as people on Twitter, Tumblr and Facebook share news pictures of huge mass demonstrations around the world, usually not discussed at any length if at all on American mainstream media, including such liberal sites as MSNBC, which focus on domestic events, with a tendency to get seduced by the horse-race aspect of electoral and party politics in the US). The smaller groups are interesting and moving in another more intimate way. I should note that including the Free University, I have attended only a couple of events in recent weeks, so my view is pretty limited but my sense is of a tender struggle, with a desire for positive social inclusion at the level of the everyday, for modest cumulative efforts to interject criticality but also small tangible moments of community and warmth into a media entertainment, corporatized, corrupted and alienated culture. Some of these efforts have a tentative aspect which may lead to media commentary of the death of Occupy, but these small meetings, as much as the larger public events such as the occupation of Zuccotti Park, at least reveal to each individual that they are not alone in their hopes and desires for a different and better world.

The turn to historical texts is significant in this regard. My totally unscientifc and personal view is that from the French Revolution, if you really want to go far back, through the Russian Revolution, to the crucible of the Great Depression with its powerful political battles between totalitarianism, fascism, communism and progressive liberalism, great union movements, and great battles for civil rights, women’s rights, and gay rights, up to the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980, the voices for political engagement were sharp, confident, fearless, funny, inspiring, historically rooted, with deep roots in the assertion of rebellion. The 1980s marked the beginning of the institutionalization of some of these voices into the university but underscored with a growing disappointment with the “failure” of the 60s and a creeping complicity with the corporatization of the world.

The turn to the historical texts and voices indicates a current thirst for the courage, eloquence, and, after thirty years of the triumph of irony, for the authenticity of such voices. At the same time it is quite interesting to note the trend towards re-performance, recently a hot subject of debate with regards to performance art. Events, political actions and interventions, and artworks whose contingent nature was completely a part of their meaning are now being not just celebrated but also re-performed under quite luxurious and heavily promoted circumstances–things artists and political thinkers did in conditions often of near anonymity, not that many such figures did not seek attention for their causes and themselves and document their practices as best they could, but I still would describe as near anonymity relative to current conditions of instant self-documentation, promotion, and commodification on pretty much everyone’s part. One problem is that questions of political belief and authenticity are still hard to bring up, in fact I type these words with censorious critical voices loudly whispering in my ear!

The interest in something like a Free University is also an indication, a recognition that things are not quite so rosy in institutions of higher education, just as they are not rosy in the public school system, in fact in every system. The moral economy of the 1% occurs in every part of culture: we see some of the public protests against the marketization of education, in faculty and student protests against closing of liberal arts departments, libraries, and archives and in the firing of even University Presidents, or, rather, some of these situations are so egregious that they actually get some coverage, but also we see the kinds of small repressions and erosions of knowledge bases that take place throughout the university system in favor of new global imperatives connected to the very same system critiqued by the Occupy movement. Some things will no longer be taught, and thus eventually some may then reappear in the small instances of extra-institutional education Free University proposes and is just one example of, or indicator of the need for–all the more significant as higher education becomes too expensive for even upper middle class people and begins to seem non-cost effective as jobs do not exist for the subjects being taught, particularly in the liberal arts and arts.

This is what has led me to be interested in extra-institutional teaching situations though perhaps it may be therefore inferred that even some such erosions and repressions take place right in the middle of the most progressive institutions in the name of the most advanced political positioning.

In this blog I have occasionally linked to some of the stirring political speeches and the closeness to historical turmoil that marked the generations before me. These framed my initiation into politics in my early teens: the admiration (the word is not sufficient) my parents’ generation had for Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt and the policies of the New Deal–which current Right Wing politics in the US are intent on finally at long last repealing, after 80 years of concerted efforts to do so. My parents’ experiences with fascism and the Holocaust and the formative experiences of their American friends in the Great Depression and during the post-war McCarthy era were a strong influence on me as I grew up listening to their stories. In recent years as labor unions have come under attack, I have often thought about the general tendency towards progressive political thinking within immigrant groups in the US that had experienced political and religious repression in the lands of their birth and how these tendencies were part of what drove the labor union movement in the US in the early twentieth century. The political figures who I witnessed through the 60s and 70s had been formed in these crucibles and carried their traces still even as post-war economic conditions began to shift towards the situation we are currently struggling against. These are just some of the experiences that marked the atmosphere of the pre-1980s period as I experienced them, as were the examples of civil rights leaders and workers such as Fannie Lou Hamer and Martin Luther King Jr.

My interest in the possibilities of the structure of Free University seminars is based on experiences I have related on this blog before, in a provocatively titled and, significantly, pre-Occupy post, including one comment that alas will ring in my mind for years, a student’s negative comment in a faculty evaluation of me to the effect that “she made us listen to a speech by Martin Luther King” in a seminar on contemporary art issues (King’s “Beyond Vietnam” speech delivered April 4, 1967, a year exactly before his assassination). Apparently the market based expectations of students (how will this help me be a viable contemporary artist and promote my work?) clashed with my feeling that certain kinds of speech are more important than the orthodoxies of critical theory or some art discourse as well as art market gossip that still hold sway even as such types of speech are now being celebrated in the events that I mentioned at the beginning of this post happening this week in educational and alternative art institutions this week in New York City.

Politics is not for the faint of heart and can be mind-spinningly complex and soul-breakingly frustrating, as are most human beings, and because of that an engagement with politics can end up making people flee back to the interests of their daily lives. As in the past it is the realization that the safety and comfort of those personal lives are contingent and subject to larger historical forces that turns our attention again to political speech from other times when such threats were also great and yet a political perspective was more part of common thought.

*

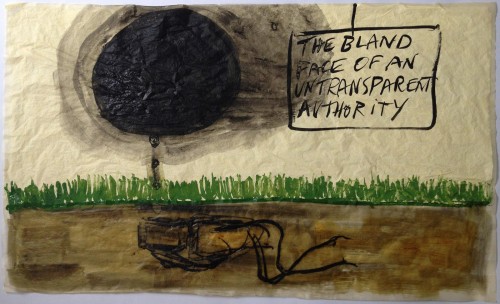

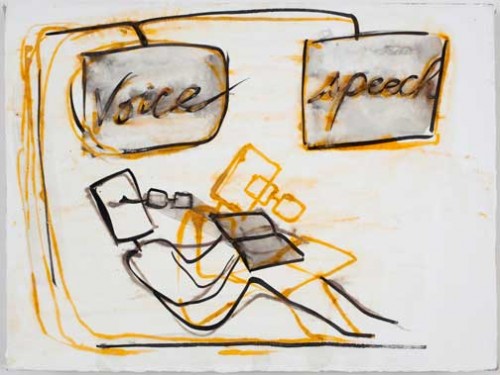

Despair and possibility for political activism through speech are also concerns of my current visual work:

Mira Schor, The Bland Face of An Untransparent Authority, ink and gesso on tracing paper, 2012 — a pessimistic realist view

Mira Schor, Voice and Speech, 2010. Ink and rabbit skin glue on gesso on linen, 2010. The optimistic activist view