The first issue of M/E/A/N/I/N/G: A Journal of Contemporary Art Issues, was published in December 1986. M/E/A/N/I/N/G is a collaboration between two artists, Susan Bee and Mira Schor, both painters with expanded interests in writing and politics, and an extended community of artists, art critics, historians, theorists, and poets, whom we sought to engage in discourse and to give a voice to.

For our 30th anniversary and final issue, we have asked some long-time contributors and some new friends to create images and write about where they place meaning today. As ever, we have encouraged artists and writers to feel free to speak to the concerns that have the most meaning to them right now.

Every other day from December 5 until we are done, a grouping of contributions will appear on A Year of Positive Thinking. We invite you to live through this time with all of us in a spirit of impromptu improvisation and passionate care for our futures.

Susan Bee and Mira Schor

*

Erica Hunt

For M/E/A/N/I/N/G

Was there ever more blinding noise set to panic?

Was there ever more thunder than thunder muted?

Is it lightning that strikes the public stare?

Is it lightning that sticks public fascination to calamity?

to siren’s sight-obliterating call?

Is it thunder or thirst that severs thirst from throat?

the sound disconnected from the picture?

Is thirst recollected by rain?

We wake up, waking, woke

to thunder outside

the house, inside, it was already

raining.

*

Writing Life / November 2016

this labor is not silent

but requires collaboration between clamor and music

found in rustling. Not makeshift, you are its prototype

an advanced draft. Sense

applied to warm skin. Uncanned mannequin

against gun robot. Stand.

Tricks in a picture. Stand.

Name the ruse of normal in criminal bracket.

Stand. Duet with double optics, then

stand to its left. If the ground is too hot to tolerate long,

improvise and stand. But

stand.

Erica Hunt, poet, and essayist, once wrote “no shade to lie down in the lullaby banks” foreshadowing the November 2016 election. She is Parsons Family Professor of Creative Writing at Long Island University, Brooklyn campus.

*

Noah Fischer: We Are Called to Fight

It turns out that the campaign advisors, though trafficking in next-level untruths, made one claim on America that isn’t exactly a lie. They dug something up that was long-rotting under the floorboards: an invention of race that split the white working class from black people (and people of color in general) in order to lay the economic cornerstone of the American Dream. This rotting thing proved extremely effective.

Wounds never healed and debt was never paid and meanwhile the monster kept eating. It began to gobble up the white middle class too, capturing hundreds of millions into odious debts securitized by mega-firms. It gobbled the Dream right up. And just when the 99% were about to wake up, it jumped into the middle of the political process and cast out a thick web of lies branching out from the invention of race and steeped in its pain. That is why we choke on language now bursting with harmful triggers, each concept certain to stab one group or the other. This is how Trump rises. We now need a deeper language and an art that includes new tunnels and pathways.

The last weeks have shown us that Trumpism is threatened by artists. It was no mistake that the last alt-right propaganda meme on the eve of the election accused performance artist Marina Abramović of devil worship (#spiritcooking). Then the cast of “Hamilton” stepped up to the moment from their stage. Brandon Victor Dixon is the actor who plays Aaron Burr who shot the father of the 1%, Alexander Hamilton. So it’s fitting that he challenged Pence. And in response The Predator-in-Chief himself tweeted that “the theater must always be a safe and special space…Apologize!” This meant: you will not be safe as long as you are free. The specialness of your industry is predicated on you shutting the fuck up.

Friends, this is a declaration of war. Because “shut the fuck up” is echoing around the globe from Russia to Israel to Poland to India. A webs of lies and a dredged corpse is poisoning our language and a “shut the fuck up” to those who try to rehabilitate it equals a war against meaning, and we are called to fight.

And there can only be one answer: preparations to join together and fight. Art practice will be our boot camp. Because if you watch Victor Dixon in his moment of protest, you will see the generously flowing movements and rich pronunciation of a trained actor-warrior. And if you go on the streets in protest, you will see that the empowered public voice and public body and paintings and songs are needed on this stage too. Even more, it’s by developing a personal relationship to intuitive beauty that one sustains the struggle. It’s by understanding the deeper logic of artistic time that we can speak truth to power even after the play had ended, after the exhibition is down, and the next day too. It’s by committing to artistic experiment that a certain risk becomes possible.

The stakes are high. To normalize what’s coming may be the riskiest path. If we do not fight, we could lose everything. Or more specifically: We artists will have much to offer the 1% who will thrive under this and any regime, and nothing to offer our comrades whose survival depends on solidarity. We have come too far to calculate that “probably me and my friends will be fine.” We learned too much about the history of power accumulation and its reliance on the privilege of silence. We know too much about the common work of emancipation.

Noah Fischer works at the crossroads between economic and social inequity and art practice and its institutions. His sculpture, drawing, performance, writing, and organizing practice fluctuate between object making and direct action as well as an ongoing theatrical collaboration with Berlin-based andcompany&Co. He is the initiating member of Occupy Museums and a member of GULF/ Gulf Labor and his collaborative work has been seen both with and without invitation at MoMA, Guggenheim, Brooklyn Museum, ZKM, and Venice, Athens, and Berlin Biennales among other venues.

*

Julie Harrison

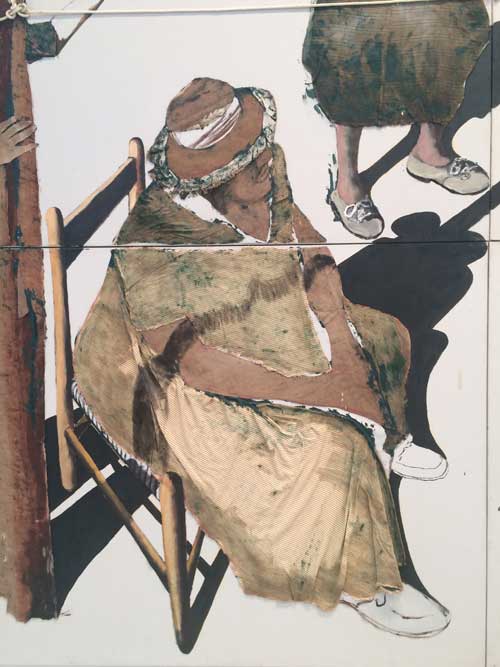

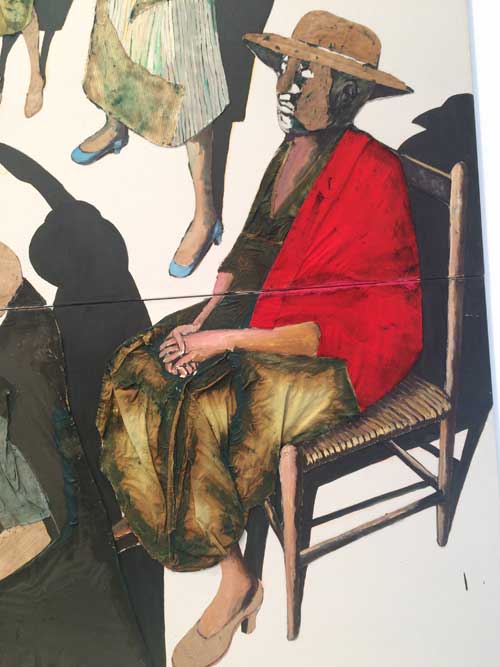

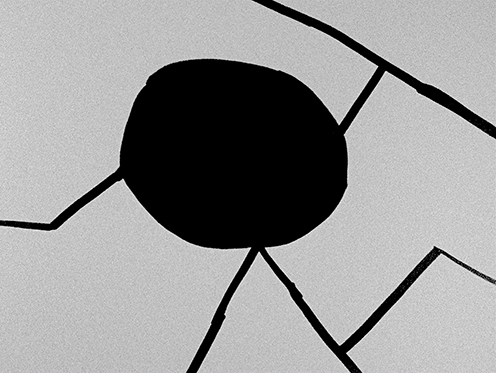

Julie Harrison, “War (Series),” 2014. Archival pigment print, 17″ x 42

Julie Harrison, “War (Series),” 2014. Archival pigment print, 17″ x 42″

On December 10, 1948, the General Assembly of the United Nations signed the UNIVERSAL DECLARATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS in Paris. This Declaration established 30 Articles that spell out what it means for the entire “human family” to be entitled to dignity, equality and inalienable rights. It is the foundation for freedom, justice and peace in the world, and has been translated into over 500 languages.

The United States has a history of violating human rights, and perhaps we can frame our work towards change as such (it doesn’t just begin with Trump, although he and his ilk will most certainly exacerbate it).

In reality (using the language written in the Declaration):

- We are not all born free and equal in dignity and rights.

- We are not without distinctions of race, color, sex, language, religion, opinion, origin, property, birth or other status.

- We do not all have the right to life, liberty and security of person.

- Some of us are held in slavery or servitude.

- Some are subjected to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.

- We do not all have equal protection of the law.

- Some are subjected to arbitrary arrest, detention or exile.

- We are all being subjected to arbitrary interference with our privacy.

- Some are not allowed the right to seek our country’s asylum from persecution.

- Everyone does not have the freedom to manifest their religion or belief.

- Everyone does not have the right to peaceful assembly and association.

- Everyone does not have the right to equal pay for equal work.

- Everyone who works does not has the right to a just and favorable remuneration.

- Everyone does not have the right to an adequate standard of living.

- Everyone does not have the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, and old age.

- Parenthood and childhood are not entitled to special care and assistance.

- All children, whether born in or out of wedlock, do not enjoy the same social protection.

- Education is not directed to the full development of the human person.

- Education does not promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups.

- Everyone does not have the right to freely participate in cultural life, arts and scientific advancement.

I recognize that we operate within degrees of this or that. But if we continue to believe that human rights abuses are THEIR problem (that OTHER country), not ours, then we have not fully understood what human rights are.

Happy 68th Anniversary to the UNIVERSAL DECLARATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS.

Julie Harrison is a visual artist, social justice advocate, avid adventurer, bohemian mother, and amateur political pundit from New York City.

*

Roger Denson: The Individual Is No Longer Invisible In There

I can’t recall an election being more about identity. That is in terms of one’s personal identity, one’s view of what identity means, and how one’s identity is a vehicle for or a hindrance to social and cultural mobility. Ironically, I found myself coming full circle, back to the early 1990s. That this circling should intersect with the “last” M/E/A/N/I/N/G publication is doubly ironic, in that my first contribution to the May 1994 issue is a commentary I called, “The Indivisible Individual Invisible In There,” what then seemed a newly emergent anti-essentialist approach to identity.

In that work I began to integrate the writing of Anthony Appiah, Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Judith Butler into my own positions on the debate of the new identity art being made in the late 1980s and early 1990s. This was an art made in the shadow of the neoconservative backlash to 1960s reforms and revolutions overseen by Reagan and Bush I. My targets were the mythologies of race, gender and sexuality, which had become ensnared in static and rigid ideological paradigms by even the most well-meaning activists leading our liberation movements. What had been fresh and vital to the defense of universal civil rights in the 1960s and 1970s came to seem stalled and stunted by the 1990s as artists and writers sought greater individuality and less ideological boundaries to move through in life and art.

Of course there had been earlier anti-essentialists who debunked the boundaries, if not the biological organs and makeup of difference. But Franz Boas and Margaret Mead in anthropology, W.E.B. DuBois in sociology, and Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir in philosophy and political theory spoke in bygone languages that a generation of Structuralists had deactivated — or so we thought. Appiah, Gates and Butler showed us these earlier modernists in fact held out the counterpoints to the notion of essence still relatively unknown within the sphere of radical identity liberation movements that deferred to traditional boundaries of racial, gender, sexual, class and ideological categories. Appiah, Gates and Butler brought just the right reframing to the anti-essentialist notions of the former Existentialist generation to make the individualism that the 1980s culture celebrated consistent with the new evidence from DNA studies that the world was not composed of static races that we had ‘arrived at’ and ‘occupy’, but rather that we ‘move through’ in ‘frequencies’ of identities and generations as we branch out and mutate with ceaseless migration and mixing of racial, ethnic, cultural and biological genetic types.

Even more than attempting to spread the diversity model paradigm, I was concerned with what such a model meant for the liberation movements that proliferated since the 1960s, yet were hardly finished with their work of securing parity for diverse populations in the 1990s. Black power, feminism and gay rights were still struggling movements, and the paradigms of classical fixed identities motivated millions. To now say that we weren’t biologically black, women and gay, that we were only culturally and consensually so, seemed at the time a dangerous deflation of those movements and even a denial of what they had achieved in the name of liberty. Yet it was because discrimination flagrantly continued despite the new empowerment movements that I wrote in M/E/A/N/I/N/G #15:

There is little doubt that identities like “man,” “woman,” “black,” “white,” “yellow,” “red,” “straight,” “gay,” “bourgeois,” and “proletariat,” are in crisis. Although these ancient identities have motivated and sustained the emancipation and empowerment movements of recent decades, we may at times find such traditional identities limiting our personal development. Nonetheless, for many the practice of shedding traditional identification with an assumed racial, ethnic, engendered, sexual, or economic class “jumps the gun,” particularly if an achievement of parity is still forthcoming. While some feel the time for a deconstruction of traditional identity along the lines of race, gender, ethnicity, economic status, and ideology has come, others, especially those who espouse an activist identity informed by feminism, black power, Native Americanism, or gay rights, the impetus to dissolve traditional identity and move beyond it poses a reactionary threat.

Fast-forward to 2016 and the end of what may be the most divisive US Presidential campaign since the 1960s. Divisive because the demographics of diverse populations made themselves heard throughout and in the outcome of the campaign. Despite that the liberation movements for women, blacks, Hispanics, Asians, native Americans and LGBT peoples have still to secure unquestionable social recognition in the institutions of the US, the once-identity-phobic public has become so keenly sensitive to the slights to one’s self-identification that all sides have become intent on silencing opposition in the media, and especially social media. And this silencing was wished from all sides, not just the reactionary far right or the intransigent far left.

If I come to focus now on my own identifications and misidentifications during the 2016 campaign, it is to ensure that the record maintains its individualist center amid all the swirling identity tropes that rely on general allegiances. For while it’s true that some of the accusations here about to be counted are merely rhetorical and inflamed — the illogic of the impoverished ploys of one-upping an opponent in a debate otherwise being lost for being devoid of principles, issues and causes — the disparagements are rooted in the reality of individuals attempting to silence one another. Still, I raise them to illustrate to what degree we have made a mockery of essentialist identities, cultures and their politics — even if we don’t realize we are expressing (self) mockery.

The point is not to focus on me and what I do and don’t believe, but to consider to what degree identity has evolved from being mythologized as a static essence to being rendered a contingency in constant evolution. The matter is more than one of identifying with or against the perceived identities that our antagonists pin on us. It is a matter of recognizing that the slippages that intervene between one’s own self-identification and the perceived identities being pinned on us are increasingly the effect of identity politics having become fully integrated into mainstream media, if not popular consciousness and expression. It is also instructive of the conceptual divide that exists between the essentialists (racists, misogynists, xenophobes, homophobes, and just plain folks identifying according to their conditioning) and the truly democratic anti-essentialists who understand that identity and identification are relative to innumerable and even unidentifiable differences between us.

It is also a matter that the rush to identify others, either habitually or intently, is too often motivated by the drive to gain personal and collective political leverage over perceived opponents. As witnessed below, a common attempt to acquire and maintain that leverage is by publicly recalling the fears of those who have been discriminated and persecuted and tagging their opponent with participating in that discrimination and persecution. Whether the accusations are true or false, the leverage is sought and maintained by resorting to the clichés of reverse racism and sexism, and that all too often render the formerly abused the newly emergent abuser. This is my point in the account below, for which I will leave to the reader the judgment whether or not this writer has been judiciously or injudiciously tagged by his critics below.

And so it is that in this year of fractious accounts of grievances, for largely rhetorical reasons, I have been called an Islamophobe and closet Zionist because I haven’t criticized Israel’s treatment of Arabs virulently enough. On the other side of the coin, I was called anti-Semitic because I condemned the Israeli eviction of Palestinians from centuries-old family land to make room for Jewish settlements. I’ve been called anti-Christian because I support a woman’s right to reproductive rights and because I denounced Christians who bombed abortion clinics. I’ve been called a religious fanatic because I consider atheists to make the same epistemologically unsound pronouncement about the unknown that religious make. I’ve been called misogynist because I believe that women too often undermine their own rights by conceding to, even supporting, patriarchal social and gender codes. I’ve been called a hater of heterosexual men because I was critical of a recently deceased famous straight male performer who was accused of raping a teenage girl. I was called a member of the oligarchical 1% because I didn’t support a Socialist-Independent presidential candidate. I was called a Communist because I didn’t support an oligarch for President. I was called a white racist because my candidate was deemed a conspirator to the commercial and lengthy imprisonment of blacks for nonviolent crimes. I was called a self-hating white because that same candidate was willing to promote the advancement of non-whites economically and politically at the (perceived) expense of whites. I was called a self-hating fag because that candidate was late to embrace gay marriage. I was called an imperialist colonizer because that candidate didn’t speak out on the Dakota Access Pipeline conflict. And I was called anti-American, because I support the Lakota and other tribes opposing the pipeline at the cost of jobs.

Again, this is not to dwell on my circumstance but to rather legitimize the emerging view that it can only be one’s own shifting circumstance in relation to all other shifting circumstances around us that we can trust, however humbly, to reframe defining ourselves and others according to an individual-centric model of identity. A model that is entirely relative to the individual-centric identities of others, yet no less self-defining. Is this or is this not the contingency-based relativist and anti-essentialist intersectional paradigm of identity and functionality that we sought since the 1960s? And can we use this paradigm as the building blocks, each different from the next, of use in rebuilding a democratic society with pragmatic capabilities to expand beyond prejudice and marginalization?

Roger Denson is a regular contributor of art and cultural criticism to Huffington Post since 2010. His feature articles and reviews have appeared in Parkett (Zurich); Artscribe International (London); Bijutsu Techo (Tokyo); Art in America; Artbyte; Arts Magazine; Art Experience; M/E/A/N/I/N/G; Acme Journal; and Journal of Contemporary Art (all New York); Duke University’s Cultural Politics (Durham, NC and London); Flash Art; Contemporanea (Milan); Trans>Arts, Culture, Media (Buenos Aires and New York); and Kunstlerhaus Bethanien (Berlin). He is the author of the forthcoming monograph, Vasudeo S. Gaitonde: The Sonata of Consciousness, 2017 (Bodhana Arts, Mumbai).

*

Robert C. Morgan: The Presence of M/E/A/N/I/N/G

The future is a conundrum, a misguided erudition of how we think things should be, but never are. It is easier to know the past; and by knowing the past, to be rehearsed in memories of thoughts gone by, which were once believed to be true. The present is perhaps the most difficult, the high wire between Points A and B, the resounding tight rope on which we may find ourselves suspended, the still transition between past and future. This is what makes the present so ironic and so difficult to perceive, to grasp and to understand.

In the 90s, I recall writing book reviews for M/E/A/N/I/N/G. This was something I enjoyed as it kept me focused on the academic side of art. But in addition to the reviews, there were other occasions that proved deeply meaningful. At the time I was too involved with the mystique of conceptual art and was looking for a way to think and to write from another direction. This happened in a brief contribution I made in one of the forums organized by the editors. My statement raised questions about the marketing of art, which in those days, were not discussed. It would eventually lead to my book, “El Fin del Mundo del Arte,” initially published in Spanish and then later the same year in English.

Through this forum, I found a way to connect with my changing sensibilities at the time. I found the courage to reject the trends of academic art writing and begin questioning the assumptions on which I was making critical judgments.

Printed publications, like M/E/A/N/I/N/G, were more likely to be seen and read in the 90s than they are today. It was a different era in art where the approach to theory and feminism seem to follow a very different course. I suppose I would call it more “open-ended” to the extent that writers were given the permission to open their minds and pursue a line of thought that was both personal and theoretical, which, of course, was something artist-writers need to do. It was a magazine that opened doors and allowed fresh ideas to move from the margins into the mainstream. There was an internal presence in M/E/A/N/I/N/G, consciously put forth by the editors. The language of the podium was removed from the premises and given back to artists interested in changing sensibilities that would enrich not only the beleaguered past and future but would put us squarely within the present. M/E/A/N/I/N/G became a harbinger for artists concerned with political change and who needed a forum by which to engage with one another on issues of discrepancy, of discrimination, of civil and human rights that are, unfortunately, still with us today.

Robert C. Morgan holds a Master of Fine Arts degree and a Ph.D. in Art History. He divides his career between painting and writing. He has lectured widely, curated numerous exhibitions (other than his own work), and has written literally hundreds of critical essays. He was awarded the first Arcale prize in International Art Criticism in Salamanca, and, in 2011, was inducted into the European Academy of Sciences and Arts, Salzburg.

*

Jenny Perlin

Jenny Perlin, Still image from “Inks,” 16mm film loop, b/w, 5 seconds, 2014. Courtesy the artist and Simon Preston Gallery, New York

“Silences and repetitions are rejected as a failure of language when they are experienced as oblivious holes or as the utterance of the same thing twice or more. WE SHOULD NOT STAMMER, so goes the reasoning, for we only make our way successfully in life when we speak in a continuous articulate flow. True. After many years of confusions, of suppressed voice and INARTICULATE SOUNDS, holes, blanks, black-outs, jump-cuts, out-of-focus visions, I FINALLY SAY NO: yes, sounds are sounds and should above all be released as sounds. Everything is in the releasing. There is no score to follow, no hidden dimension from the visuals to disclose, and endless thread to weave anew.” —Trinh T. Minh-Ha,“Holes in the Sound Wall,” from When the Moon Waxes Red: Representation, Gender, and Cultural Politics, Routledge, New York, 1991

—

“We must acknowledge that we began [in cinema] like literary people, that we’re not sufficiently literate in existing sounds and don’t distinguish among them. If […] you go to the Donbass, then all you’ll hear [at first] is one uninterrupted roar and noise—that’s the first impression. But this wasn’t my first time in the Donbass; I studied these sounds and saw that, yes, we really are domestic, and for us these sounds are “noise”—but for the worker in the Donbass every sound has a specific meaning; for him there are no “noises.” And if it seems to you, comrades, who know all the scales perfectly, that I am at this moment emitting pure noise, then I can assure you that I am [producing] no noise whatsoever.” —Dziga Vertov, spoken at the Kiev preview of “Enthusiasm,” RGALI f. 2091, op. 2, d 417, 1. 59, in John MacKay, “Disorganized Noise: Enthusiasm and the Ear of the Collective,” Kinokultura # 7, January 2005

—

“The optical thought the optical dance to the sound of the river of your soul The flowers of a mind The dance of handwriting and the song of flowers and the white of the clouds and the blue of the sky–Sometimes it is dark and you see in the darkness nothing but your own feeling your own movements your own pulse and the rapture of your heart your blood this is what you see–what goes with the music–The Stars the Heaven the Darkness and the Light of your own love your own heart The Light of your mind, The Dancing Light of your blood–and your feeling.” —Oskar Fischinger, on Motion Painting No. 1, from Center for Visual Music’s Fischinger Texts: Film Notes.

—

“CHINESE CURIOS”

‘These are days when no one should rely unduly on his “competence.” Strength lies in improvisation. All the decisive blows are struck left-handed.’”—Walter Benjamin, from One-Way Street and other Writings, NLB, London, 1979

—

Jenny Perlin is an artist working in Brooklyn. Her practice in 16mm film, video, and drawing works with and against the documentary tradition, incorporating innovative stylistic techniques to emphasize issues of truth, misunderstanding, and personal history. Her projects look closely at ways in which social machinations are reflected in the smallest fragments of daily life. Perlin’s films often combine handwritten text and drawn images and embrace the technical contingencies of analog technologies.

*

Altoon Sultan

—“I am here to wonder.” Goethe

It is difficult to understand how to respond to the political shock that descended on so many of us in early November. Where to turn, how to think, what to do? For me, it is necessary to go towards what I find essential, which is paying attention to the small moments that bring joy and beauty and surprise: winter sunlight reaching far into a room, highlighting the delicate serrated edge of a seed head; a tiny snail crossing an immensity of leaf; bright light illuminating a plastic tank; the taste of a garden tomato warmed by the sun; a tangle of tree roots pushing against city pavement; the emergence of a seedling, still a miracle to me. To slow down and notice everyday things provides sense and spirit and calm to emotional chaos.

—“The moment one gives close attention to anything, even a blade of grass, it becomes a mysterious, awesome, indescribably magnificent world in itself.” Henry Miller

I walk in the woods, taking the same path several times a week, and each time it is different in feeling and in light, each time there are things to see that I hadn’t noticed before: a bit of moss, a fluff of seeds, a leaf dangling from a spider’s thread, all marvels.

—“I think what one should do is write in an ordinary way and make the writing seem extraordinary. One should write, too, about what is ordinary and see the extraordinary behind it.” Jean Rhys

And there is art, my own and the sweep of art history. In my painting and sculpture I too attempt, like Jean Rhys, to transform the ordinary and overlooked; details of farm machinery––panels and bolts, light and shadow crossing metal and plastic surfaces––become complex formal compositions. When I was a younger artist I felt the need to make large dramatic paintings, but now I value intimacy and close looking. And I value being part of a very long tradition of picture making by Homo sapiens going back 40,000 years, when humans painted in caves, making images of remarkable sensitivity. We don’t know the purpose of these paintings, but to me they indicate a need to recreate the world, to make something beautiful from nothing. Across millennia peoples have made images and have decorated objects, not from necessity but from desire. One of my deepest pleasures is to wander the galleries of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NYC for hours, crossing the globe, visiting favorite objects and discovering new ones. I’ve long felt that art-making was an essential part of being human but was nevertheless startled to read the following while writing this piece; it appears in the NY Review of Books, November 24th issue, in a review about brain science by the early pre-history professor Steven Mithen. He asks “what gave us ‘the Homo sapiens advantage’?”

It wasn’t brain size because the Neanderthals matched Homo sapiens. My guess is that it may have been another invention: perhaps symbolic art that could extend the power of those 86 billion neurons.…

I am part of a tradition of making; I am part of the world. In paying close attention to both, I find meaning.

Altoon Sultan lives on an old hill farm in the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont, where she makes art and tends her garden.

***

Two more installments of M/E/A/N/I/N/G: The Final Issue on A Year of Positive Thinking will appear here this week. Contributors will include Susan Bee, Mira Schor, and more.

M/E/A/N/I/N/G: A History

We published 20 print issues biannually over ten years from 1986-1996. In 2000, M/E/A/N/I/N/G: An Anthology of Artists’ Writings, Theory, and Criticism was published by Duke University Press. In 2002 we began to publish M/E/A/N/I/N/G Online and have published six online issues. Issue #6 is a link to the digital reissue of all of the original twenty hard copy issues of the journal. The M/E/A/N/I/N/G archive from 1986 to 2002 is in the collection of the Beinecke Library at Yale University.