The first issue of M/E/A/N/I/N/G: A Journal of Contemporary Art Issues, was published in December 1986. M/E/A/N/I/N/G is a collaboration between two artists, Susan Bee and Mira Schor, both painters with expanded interests in writing and politics, and an extended community of artists, art critics, historians, theorists, and poets, whom we sought to engage in discourse and to give a voice to.

For our 30th anniversary and final issue, we have asked some long-time contributors and some new friends to create images and write about where they place meaning today. As ever, we have encouraged artists and writers to feel free to speak to the concerns that have the most meaning to them right now.

Every other day from December 5 until we are done, a grouping of contributions will appear on A Year of Positive Thinking. We invite you to live through this time with all of us in a spirit of impromptu improvisation and passionate care for our futures.

Susan Bee and Mira Schor

*

Note to email subscribers: the video in this post can only be viewed if you are online, it will not run in your email program.

*

Sheila Pepe: The United States of Calvin

In 1856, one-time pastor and faculty of the Harvard Divinity School Ralph Waldo Emerson published English Traits. As an introduction to a text that exhaustively conveys all favorable traits of the Englishman, Emerson a champion anglophile, asserts the precision of race as not only historic, but also plainly scientific. “It is race, is it not?,” Emerson asks, “that puts the hundred millions of India under the dominion of a remote island in the north of Europe.” His answer is yes. No wonder he was late to the idea of abolition.

Less than seventy-five years later, in 1928, the Harvard Theological Review (Vol. 21, No.3, Jul., pp.163-195) publishes Kemper Fullerton’s “Calvinism and Capitalism.” Within these thirty-two pages many ends are achieved. Most important is, as the title conveys, building a finer point upon Max Weber’s ideas connecting “Protestantism and money making.” For Fullerton the Protestantism key to leadership in modern American Capitalism is specifically Calvinism. Lutheranism doesn’t quite make the grade. Catholicism would catapult us back into the Middle Ages, as Catholics cling to professions in the handicrafts, rather than that of financier, industrialist, or technical expert. Consider the year it was published. In 1928 New York Governor, Catholic and reformer Al Smith was running for president. Wall Street was riding high and Prohibition, which Smith ran against, was in full swing. The Republicans had failed to reapportion Congress and the Electoral College after the 1920 census (which had registered a 15 percent increase in the urban population). Smith lost to Herbert Hoover in a landslide. Many ascribed the loss to the three “P’s” – Prosperity, Prejudice, and Prohibition.

Both the Puritans of Boston Bay Colony and the Dutch Reformed traders of New Amsterdam were Calvinist-based communities. Both built secular societies that were completely religious by design. That is, they believed that man lay bare in the unmediated presence of God. That each individual had an obligation to that God to live a highly disciplined life persistently in pursuit of good works in a secular world. Good work was not social work, rather productive, profitable work. “The Calvinist practised (sic) self-discipline not even to secure assurance (that he was elected for salvation); he practised it for the glory of God, and in the practise of it assurance came.” As Fullerton argues, this is the perfect platform for modern capitalism. Tireless money making at the expense of others is not bad, but there were limits – flagrant avarice was not seen as appropriately ascetic.

As founding father and Boston-born Ben Franklin would say, “A penny saved is a penny earned.” This seems a benign enough aphorism for his young America, even while fueled by a mandate from heaven. What the good humor and simplicity belies is that this country wasn’t simply founded by oligarchs, but by a religious oligarchy that squarely placed duty to God in the secular commons. This is not new; it simply persists.

As we look to find ways to change the damage done in this last presidential election, let’s consider U.S. values as a set of religiously formulated dictates, not the least of which is, for example, the construction of race in the service of making money for the glory of God. No one is out of the loop on this one – whether or not there was or is a “God” in your life. We might wonder where exactly the separation of church and state is in this country, and if the toleration of difference in the service of commerce is adequate expression of civil rights.

It’s time to ask again, and hopefully for the last time: What is this secular church that calls itself America?

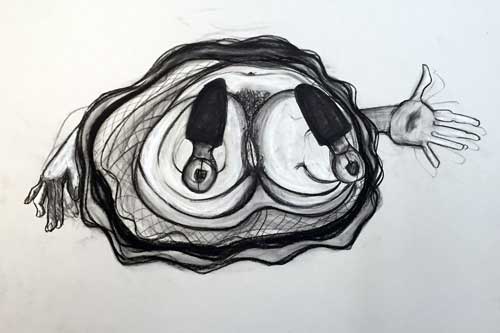

Sheila Pepe, “Glass Ceiling Fantasy,” 2006. Charcoal + chalk on grey paper

Sheila Pepe lives and works in Brooklyn. She is a resident of the Sharpe-Walentas Program. Pepe is working on an exhibition and book with Gilbert Vicario, Chief Curator of the Phoenix Museum, AZ.

*

Joseph Nechvatal

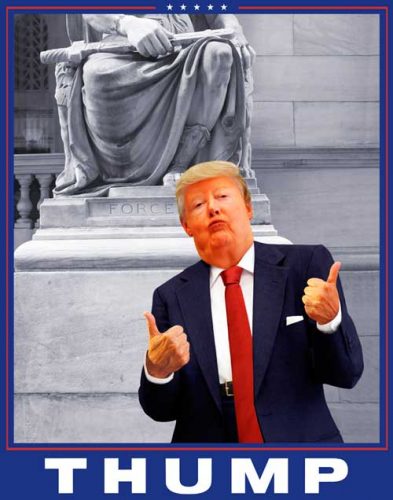

Joseph Nechvatal, Portrait of the 45th President of the United States, 11/2016 (dimensions variable)

For this digital painting entitled Portrait of the 45th President of the United States, I have taken an official Wikipedia photo portrait of Donald Trump and buried it in visual noise, denying his presence to a large degree. The idea is to visually refuse to acknowledge him clearly as president. To stop reproducing him and his brand as presidential. To resist and oppose him with noise.

Joseph Nechvatal’s computer-robotic assisted paintings and computer software animations are shown regularly in galleries and museums. Towards an Immersive Intelligence: Essays on the Work of Art in the Age of Computer Technology and Virtual Reality (1993-2006) was published by Edgewise Press in 2009. In 2011, Immersion Into Noise was published by the University of Michigan Library. His collected critical art reviews at Hyperallergic can be accessed here.

Martha Wilson as Donald Trump: Politics and Performance Art are One and the Same.

Grace Exhibition Space May 29; Smack Mellon, July 31, 2016; Creative Time Summit/Transformer party, October 13, 2016; P.P.O.W “Inauguration” exhibition, October 28; Tara benefit November 6, 2016.

Enter to Queen, “We are the Champions”

Hello America! People keep asking me how I’m going to make America great again. How I’m going to make America safe again. It’s you and me baby—we’re going to do this together.

It’s the coming of the solid state

When we’ll all be together again

Just like—I can’t remember when

We’ll have paradise on Earth at last

It’s the coming of the solid state

Instantaneous control’s what it takes

No more dropouts to spoil the view

Our society will be so cute!

It’s the coming of the solid state

When morality follows interest rates

Making money’s a right God-given

Here’s to Calvin—is it Coolidge or –ism?

(Put on glasses)

I don’t care if you record me talking about grabbing women’s pussies; however, I never let photos be taken of me wearing glasses. I don’t want to look like a 4-eyed egghead LOSER. But this performance is in the artworld, which does not count.

Hi! I am Martha Wilson, an artist and an arts administrator dressed up like Donald J. Trump. In all my previous performances, I have endeavored to go completely into Nancy Reagan, Barbara Bush and Tipper Gore’s brains, so see what it’s like in there. But I had to turn off Donald’s speech to the Republican National Convention. I am here today wearing both personae to say a few words about how I have seen the relationship of art and politics evolve during the last 50 years.

In the 1960s, the Vietnam War was like a black curtain hanging behind everything. The cultural scene was one of protest, with marches, sit-ins, teach-ins, tax protests, non-violent and violent confrontations of ideas. Kent State was perhaps the nadir of this time, when the National Guard shot and killed students. People left America for Canada; I was one of those. It was a time when neither side would listen to the complaints of the other; our society was truly divided.

The 1970s saw Watergate go down. This is when Richard Nixon’s dirty tricks were exposed; he had to take responsibility and was impeached. The way this happened was that Robert Redford, a successful actor, paid Washington Post journalists Woodward and Bernstein to research and publish what the administration was up to.

In the artworld, artists of the 1970s were inventing postmodernism, becoming socially conscious, and invading the commercial gallery scene with temporary installations and video. Performance art, too, was entering the mainstream through the bar scene. There was recognition that the artworld was a white place: artists who were white were engendering dialogue through friendship with artists of color; Jenny Holzer’s friendship and collaboration with Lady Pink comes to mind.

In 1980, Ronald Reagan was elected. Although as President of the Screen Actors Guild, he started out as a liberal, after he married Nancy, she persuaded him it was politically smarter to be conservative. He in turn chartered Frank Hodsoll with shutting down the National Endowment for the Arts, the agency put in place by Richard Nixon to fund the arts. In the beginning the NEA and the U.S. Information Agency were seen as a way to project America’s cultural hegemony (Abstract Expressionists had fled Europe as a result of World War II). We were better at art than anyone else, plus Abstract Expressionist art kept its mouth shut. However, when Franklin Furnace tried to send politically explicit artist book works to South America through the U.S. Information Agency, they were rejected. Later, the agency itself was killed off.

Back to Frank Hodsoll: the first thing he did was kill off the NEA’s Critics Fellowships. We, the arts organizations, did not see that the goal would be to kill off artists’ fellowships as well, and later to “professionalize” the art spaces.

The Culture Wars began in the late 1980s with the furor caused by Robert Mapplethorpe’s show, “The Perfect Moment,” as it traveled. Dennis Barrie, Director of the Cincinnati Center for Contemporary Art, lost his job as a result of his decision to take this show containing explicit images of S & M practice. The Culture Wars were fought over sexuality as a legitimate subject of contemporary art. After a lawsuit brought by “the NEA Four” Karen Finley, John Fleck, Holly Hughes and Tim Miller made it all the way to the Supreme Court, the arts community lost—the Court installed “community standards of decency” over artists’ First Amendment right to free expression.

This brings us to the 1990s, and the notion that no tax dollars should be paid for “obscene art.” This decade is when the Internet became widely accessible and artists started looking at surveillance instead of sexuality as the locus of threat. Meanwhile, the locus of the Culture Wars changed too, from art to a more granular and local series of battles over women’s reproductive choice; “balance” of equal numbers of radical and conservative views on university faculties; free speech granted to corporations; and Super Pac money allowed to influence public thought.

As Donald, I represent a beacon of hope for the white working class because I am so rich nobody can buy me. I represent their desire to shake up the binary political system–or just fuck things up. I let the barking dogs of racism, sexism and xenophobia run free. Meanwhile, Republican donors and party leaders are getting behind me because I WON… the nomination. They figure, as in the case of Bush vs. Gore, they can still control the political outcome of my presidency.

(Take off glasses)

Tit for tat and tat for tit

Politics is made of this

You give me this

I’ll give you that

And we’ll both smile

Publicity’s our strategy

And due to public memory

Which lapses so conveniently

In a few years

We can raise a family

No scandal’s bad enough to flee

The United States is still all milk and honey

Toooo meeeeee!

I will make America great again. I will make America hate again. I will make America white again. I have already made politics and performance art one and the same.

Good luck!

Martha Wilson is a pioneering feminist artist and art space director, who over the past four decades created innovative photographic and video works that explore her female subjectivity. She has been described by New York Times critic Holland Cotter as one of “the half-dozen most important people for art in downtown Manhattan in the 1970s.” In 1976 she founded Franklin Furnace, an artist-run space that champions the exploration, promotion and preservation of artist books, temporary installation, performance art, as well as online works. She is represented by P.P.O.W Gallery in New York.

*

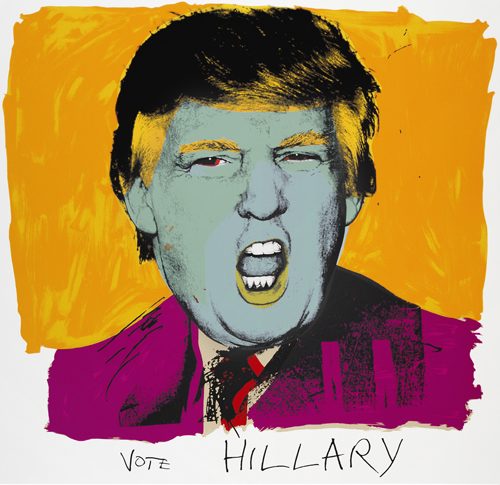

Deborah Kass

Destroyed by the election and have nothing to say about anything yet. Too hard to process the current reality. Other than experiencing sheer terror, incredible sadness, and grief.

Deborah Kass is an artist whose paintings examine the intersection of art history, popular culture and the self. Kass’s work has been shown nationally and internationally. The Andy Warhol Museum presented “Deborah Kass, Before and Happily Ever After, Mid- Career Retrospective” in 2012, accompanied by a catalogue published by Rizzoli. Her monumental sculpture OY/YO located in Brooklyn Bridge Park became an instant icon, appearing on the front page of the New York Times and was a beloved destination in NYC. In 2014, Kass was inducted into the New York Foundation for the Arts Hall of Fame. Kass’s work is represented by the Paul Kasmin Gallery.

*

Bradley Rubenstein: It’s Not Blood, It’s Red

11/22/2016

Dear Susan and Mira,

Thank you so much for inviting me to contribute a thought or two for this, your final issue, of M/E/A/N/I/N/G.

As artists, we come into our practice largely by finding, and in some ways imitating, figures from whom we imagine we might model ourselves. Barnett Newman’s concept of the “citizen artist” has always loomed large for me, and, I believe, his example might have been in your minds when you started M/E/A/N/I/N/G. His writings, letters to editors, and sometimes even his work (Lace Curtain for Mayor Daley, 1968) reflected a mind attuned to both aesthetics and the delicate fabric of society. Of course there are other examples, both historical and contemporary, who saw their work as part of a larger practice. Jacques-Louis David, Eugène Delacroix, Alexander Rodchenko and Varvara Stepanova, and Ana Mendieta come to mind.

Does the artist occupy a large role in the body politic? It is somewhat paradoxical that, in the age of Twitter and Instagram, media that privilege the image over the printed word, fewer works of art transcend the ocean of random images. Deborah Kass’s Vote Trump (2016) print edition, despite its complex appropriational historical context, remains one of the few iconic visual works from this election cycle to capture the attention of the public; iconic because it combined a complex historically informed sensibility with graphic effect. To be honest there are no other images that come to mind because, I fear, our current academic culture is not developing a student body willing to engage in public discourse, perhaps due to our trigger-warning, microaggression-fearing culture of safe spaces that has begun to privilege isolation and the cult of victimization over political action and social participation. It might be cautionary to remind younger artists that there is a difference between censorship and persecution (like having your press destroyed, or being imprisoned) and merely being actively ignored. There are artists in other countries who could remind us of this difference if only they weren’t busy being tortured at the moment; Iran, for example, doesn’t have many judgement-free zones.

This is not to say that we should just throw up our hands and admit creative failure. Rather, we might take stock of our time and be attentive, and when necessary, active in our role. When you asked me to contribute to your final issue I was unsure of what I might write, draw, or print that would encapsulate the many disparate thoughts that I have regarding art and culture at the moment. A truckload of ideas were sketched out, discarded. I went back to Newman’s letters hoping for some inspiration, direction. In the end I came to realize that sometimes just being present, and supporting one’s fellow artist-citizens when called upon, might be the most important form of resistance there is. If there is one message that we might take away from 30 years of M/E/A/N/I/N/G, it is that “if you can still read this there is hope.”

With best regards,

Bradley Rubenstein

Bradley Rubenstein is a painter and writer who lives and works in Brooklyn, NY.

*

Lenore Malen: What Now?

It was a summer of total anxiety and compulsive poll watching and now shock, despair, fear, along with remorse for what I’ve failed to see and failed to do.

A couple of years ago when politics were as usual I wrote a short essay for the Brooklyn Rail on the subject: “What is Art?” Quoting Leon Golub, I said: “If you are extremely worried about the state of the world and believe that art with its myriad of contradictions can’t stand up to it, think of Golub’s book Do Paintings Bite? in which he writes: “Art retains a residual optimism in the very freedom to tell.” “Last week one of my students said to me: “Now we have a real reason for making art.” Yes, but in truth, it is only art.

A hope and a plea: Take action immediately in whatever ways we can, each of us, so that the very worst doesn’t happen here, can’t be normalized, doesn’t last. At the same time be worried about climate, race relations and other grave divisions here, the tinderbox of the Middle East, North Korea, Britain, France, Turkey, and everywhere — everything at once. Stay in touch.

I’m very sad to think of this as the last issue of M/E/A/N/I/NG, which, when it began, was the only journal especially devoted to contemporary artists in their studios, and has continued to function as such for so many years. It’s a totally unique publication, not academic, not literary, but rather a voice for practicing visual artists — unedited, uncensored in any way.

Reversal from Lenore Malen on Vimeo. Reversal: The central scene of a 3-channel installation. A United Nations address to the human species by a horse character declaring a list of atrocities exacted on non-human animals by humans.

Lenore Malen uses the lens of history and humor to explore utopian longings, dystopic aftermaths, and the sciences and technologies that inform them. Recently her explorations have focused on ecology, on cultural myths, and on the unstable boundaries between humans and animals. She teaches in the MFA Fine Arts Program at Parsons The New School. Her show Scenes From Paradise will be on view at Studio 10, 56 Bogart St., Bushwick, NY, January 6, 2017–February 5, 2017.

*

Peter Rostovsky

Peter Rostovsky, Green Curtain, 2013, 78 x 50 in., oil on linen.

The curtain is a barrier. It demarcates time: the closing of a chapter, the beginning of another. For ancient painters and modern philosophers, it has served as a metaphor for representation—a surface that always promises a depth that is not there. For others, like me, it is perhaps an adequate symbol of this dark moment, that feels like the end, but could be—if we make it so—a new beginning, too. Like many, I lurk on the boundary, stretched over its threshold and balanced on this uncertainty, constantly reviewing the program notes, and guessing the next act.

Peter Rostovsky is a Russian-born artist who works in painting, sculpture, installation, and digital art. His work has been shown in the United States and abroad and has been exhibited at The Walker Art Center, MCA Santa Barbara, PS1/MOMA, Artpace, The Santa Monica Museum of Art, The ICA Philadelphia, the Blanton Museum of Art, S.M.A.K., and private galleries. Rostovsky also writes art criticism under the pen name David Geers. Focusing on the convergence of art, politics and technology, his writing has appeared in October, Fillip, Bomb, The Third Rail Quarterly, The Brooklyn Rail and Frieze.

***

Further installments of M/E/A/N/I/N/G: The Final Issue on A Year of Positive Thinking will appear here every other day. Contributors will include Alexandria Smith, Altoon Sultan, Ann McCoy, Aziz+Cucher, Aviva Rahmani, Bailey Doogan, Erica Hunt, Faith Wilding, Hermine Ford, Jennifer Bartlett, Jenny Perlin, Joy Garnett and Bill Jones, Joyce Kozloff, Judith Linhares, Julie Harrison, Kat Griefen, Kate Gilmore, Legacy Russell, LigoranoReeese, Mary Garrard, Maureen Connor, Michelle Jaffé, Mimi Gross, Myrel Chernick, Noah Dillon, Noah Fischer, LigoranoReese, Rachel Owens, Robert C. Morgan, Robin Mitchell, Roger Denson, Susanna Heller, Suzy Spence, Tamara Gonzalez and Chris Martin, Susan Bee, Mira Schor, and more. If you are interested in this series and don’t want to miss any of it, please subscribe to A Year of Positive Thinking during this period, by clicking on subscribe at the upper right of the blog online, making sure to verify your email when prompted.

M/E/A/N/I/N/G: A History

We published 20 print issues biannually over ten years from 1986-1996. In 2000, M/E/A/N/I/N/G: An Anthology of Artists’ Writings, Theory, and Criticism was published by Duke University Press. In 2002 we began to publish M/E/A/N/I/N/G Online and have published six online issues. Issue #6 is a link to the digital reissue of all of the original twenty hard copy issues of the journal. The M/E/A/N/I/N/G archive from 1986 to 2002 is in the collection of the Beinecke Library at Yale University.