I’m going to Paris next week for the first time in 26 years. Despite my French education at the Lyçée Français de New York, I have spent relatively little time in Paris, in France, and have complex feelings about speaking French–having been bilingual, I allowed the language to rust. Yet my emotions about Paris run deep. Last week, looking at a map of the Arrondissement I will be staying in, reading names of streets and boulevards, I began to sob and, at great expense, bought myself one extra day.

October 10 is my sister Naomi Schor’s birthday. She would be 76 years old. She died 18 years ago December 2, 2001. It is such a long time ago. I sat down in the subway the other day and realized the lady sitting down next to me was an old friend of my sister’s. She was off to work, a professor, like my sister, but she was still teaching. I am meeting another friend of my sister’s in Paris and we plan to toast our long friendships and the role Paris played in our lives, at La Coupole.

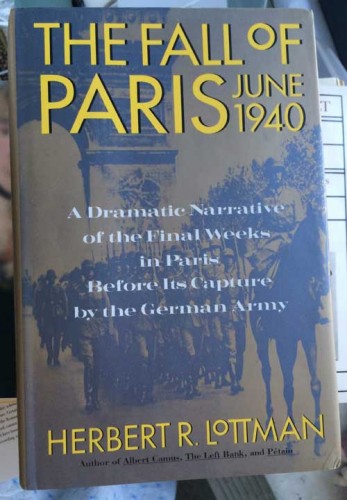

I bring this up because my sister loved Paris and knew it well, spending in the aggregate several years of her life there. Before that my parents, young Polish artists, had lived in Paris, fleeing for their lives in June 1941. They would have probably settled there permanently had it not been for the war.

I will let my sister speak:

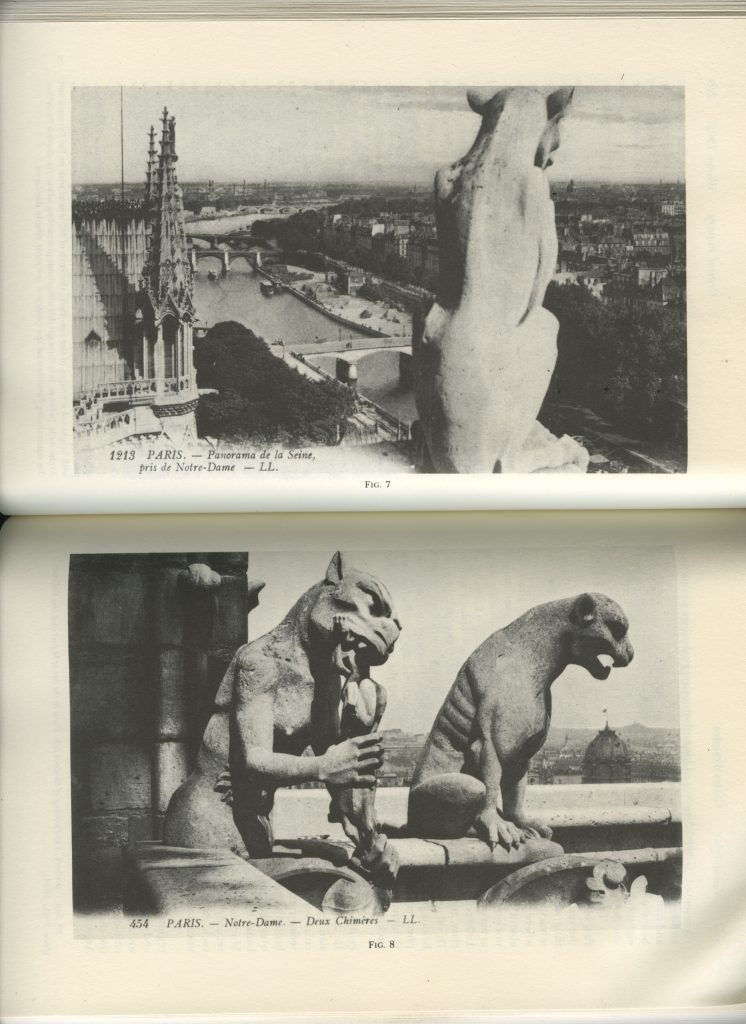

from her 1992 essay, “Cartes Postales,” in Critical Inquiry, Winter 1992: she noted that collectors of postcards are advised to focus on one category, often the city or even the street where they live:

“from the outset [as a collector turn of the century postcards] I was drawn to postcards of a place where I neither live nor work, France, and very quickly within France, Paris. This choice suggests the inadequacy of a model based strictly on an unexamined notion of one’s place of birth, work, or daily life as grounding one’s identity, what Biddy Martin and Chandra Talpade Mohanty call the “unproblematic geographic location of home.” This model cannot account for the possibility of a dis-location constituting the foundation of one’s being, or at any rate one’s collecting, but as we have seen for the collector being and collecting are intimately related. In Martin and Mohanty’s text the “illusion of home,” or of at-homeness is shattered by the realization that “these buildings and streets witnessed and obscured particular race, class, and gender struggles.” This is the postmodern, post-colonialist condition: what is at first experienced as a secure, identity-giving and sheltering space is revealed to be a place of bloody struggle and exclusion. Like the unheimlich, in whose semantic field it participates, home is a word whose positive connotations are undermined by an antithetical and negative meaning.

For me the home that is not home is Paris: but what is hidden there is a form of violence and racial struggle not generally understood today when the trinity of race, class, and gender is invoked. I am speaking of anti-Semitism, theirs not mine. My parents, Polish Jews, left Poland in the late thirties with the intention of settling in Paris. In June 1941, they along with thousands of others fleeing Hitler’s impending arrival left Paris and headed South. They were among the lucky ones; unlike Benjamin and the countless others who did not make it, they eventually crossed the border between France and Spain and settled in New York. French was my first language and the language in which I was educated. In 1958 I visited Europe and Paris for the first time. Since then, as a professional student of the French language and culture I have been back often. Perhaps someday, I fantasize, I shall retire to Paris. For now I have chosen to write on it, in order to come to terms with a longing, a fascination, an ambivalence, unfinished business.

These are pictures taken on October 8, 1965 as my sister departed New York City for Paris on a Fulbright Scholarship. She had first visited Paris in 1958 when my parents took us back on what effectively was a test of their new identities as Americans, as New Yorkers. Having fled the city they loved, returning as successful naturalized citizens with two American children, might they be tempted to return to live in Paris? The trip clarified that their lives were now in America. My sister returned to France August 1961, shortly after my father’s death, having won a poetry contest whose first prize was a trip to France where she was treated like a visiting celebrity on a countrywide tour. Now she was returning for real, as a “Fulbrighter!” I am always struck by these pictures, captured by the ship photographer, first of her walking alone towards the boat, exemplifying the difference between us then and later, her dignity and sober elegance and her love of travel and adventure, second as what for me was always the epitome of elegance, an Audrey Hepburn moment, sunglasses, about to go up the gang plank, one patent leather clad foot tipped up ever so delicately as she balanced her bag on her knee.