My father Ilya Schor was an artist. He is best known for his work in Judaica including Torah Crowns, Candelabras, and Mezuzahs, for his jewelry, and for his illustrations of treasured texts of Jewish religious philosophy and folk literature by Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel and Sholem Aleichem.

Ilya Schor, Torah Crown, detail: The Sacrifice of Isaac, pierced and engraved silver, c. early 1950s, c. 12 inches high. I can remember when my father completed one of the five Torah Crowns he made: he wore it on his head as he came out of his studio, which was in our apartment, and the bells (all details individually crafted by my father) made a beautiful sound, or, as my mother put it many years later, "had a beautiful sonority." For me as a child, what a joyful and wondrous experience of art and of religion understood through art! To my knowledge this particular Torah Crown was destroyed in a synagogue fire in the 1950s.

Ilya Schor, "Kaballah," one of 15 wood engraving illustrations to "The Earth is the Lord's" by Abraham Joshua Heschel, 2 1/2 x 3 1/4 inches each, 1949

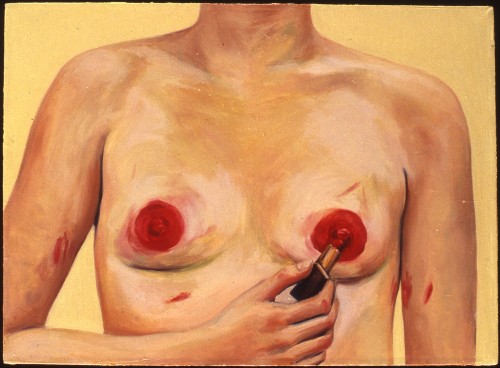

In relation to the history of modernism, my father was perhaps a somewhat unusual artist, sometimes of his time, sometimes not: an exquisite piece of his jewelry is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum and was included in an exhibition of jewelry (my memory is that it was a show of gold jewelry but can’t find the source): his work was of course among other works from the second half of the twentieth-century but among the bold abstract blobs of metal, his delicately wrought figurative piece seemed to have mistakenly strayed from a show of Benvenuto Cellini.

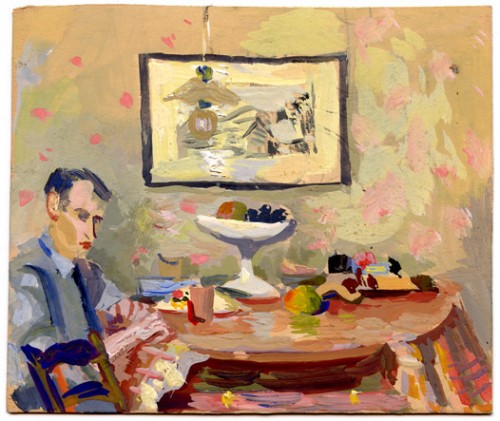

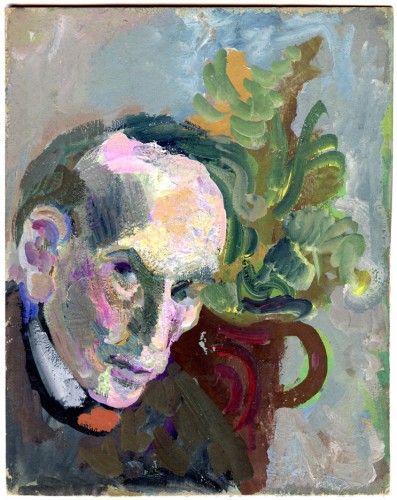

I believe also that my father was an unusually gifted artist. I know, you’d assume that of course I think so, but as anyone who knows me can attest, love doesn’t necessarily alter my critical viewpoint when it comes to art. My father drew and painted and engraved and more, as he breathed, in fact given his early death, more effortlessly than he breathed, and always his work delighted, which is in itself unusual. I’ve already written a bit about my parents’ work: in my essays “Modest Painting” and “Blurring Richter” I situate the source of some of my critical point of view in my father’s work. In “Modest Painting” I write: “Every stroke of paint carries art historical DNA, and in my father’s paint stroke there is the influence of the shimmering loosening of local color found in the work of Pierre Bonnard or Vuillard (modest masters, both) but the humility of traditional Hasidic life is reflected in the reduced style quotient in his work.”

I hope in the next few years to create an artistic biography of both my parents, Ilya and Resia Schor, but in a sense mine also that will rely on their visual legacy while weaving in textual commentary on the histories they lived through — in my father’s case, childhood in the deeply Hasidic world of the Eastern European shtetl, my parents’ shared experience of the creative ferment of their generation of left-wing, secular Jews coming of age between the Wars, the artworld in Paris in the late 1930s, flight from Paris days before the Nazis arrived, loss of their entire families in the Holocaust, immigration to America, life in the New York artworld in the 1950s, and more. As I find archival material and try to document more of their work as I find it, bits and pieces of short essays have been spilling around my head, much as the essays that eventually ended up in my book A Decade of Negative Thinking, which I moved about in my mind like a ten year long game of three-dimensional virtual chess. I hope I will be able to find a form or several forms for this task because the story of their work is the subtext of my own relationship to artmaking and to the major discourses of contemporary art and I think it offers something unusual, foreign, historic, yet still valuable to contemporary art.

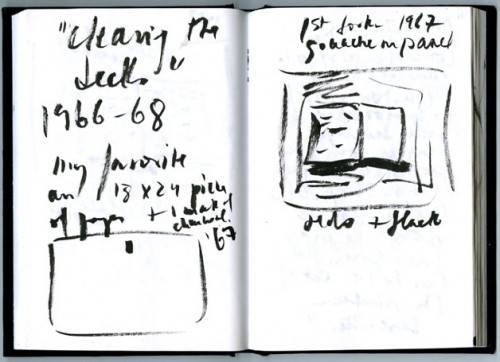

To celebrate Father’s Day this year I want to just focus on a few small gouaches on board or paper, made in the early 1940s. Many of my father’s paintings are worked on the verso side, and, if an object in silver, gold or brass, on every surface visible and hidden, so many of these little paintings have another painting, sketch, or drawing on the verso side.

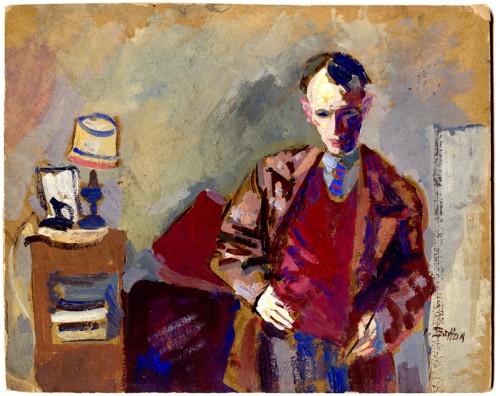

Ilya Schor, Self-Portrait with Brush, mid-1940s, gouache on board, c. 9 x 12 inches, painted in New York

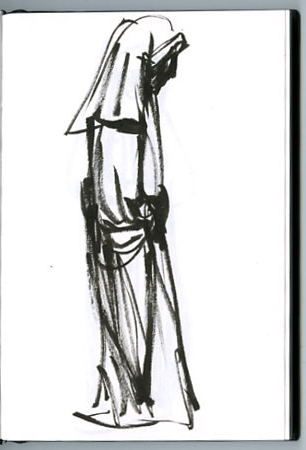

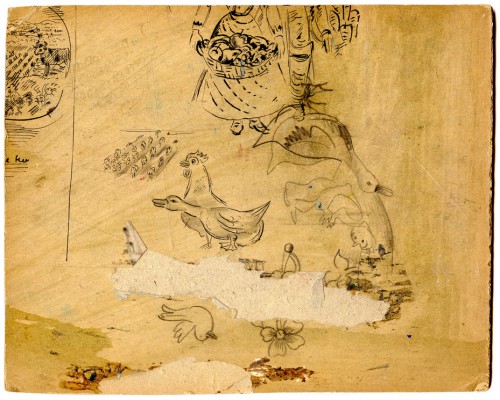

Ilya Schor, Verso of Self-Portrait with Brush, ink on board, mid-1940s. My father came by this imagery both through his roots in the folk culture of his childhood, the history of illustration and from growing up in the shtetl part of the town of Zloczow (Galicia, Austro-Hungarian Empire, now the Ukraine) with a strong connection to rural life.

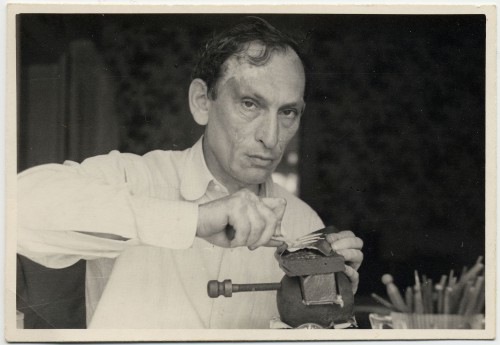

I always found great pleasure in my father’s love of drawing and the delicacy and skill of his lines no matter what medium. I loved to watch him work: his movements were quick and skilled, his touch was deft.

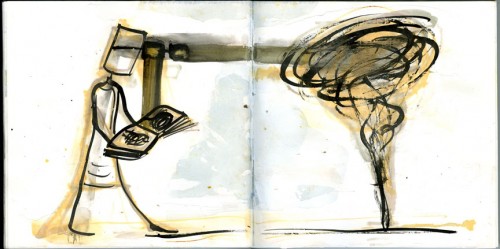

Ilya Schor, Woman Reading, gouache on board, mid-1940s

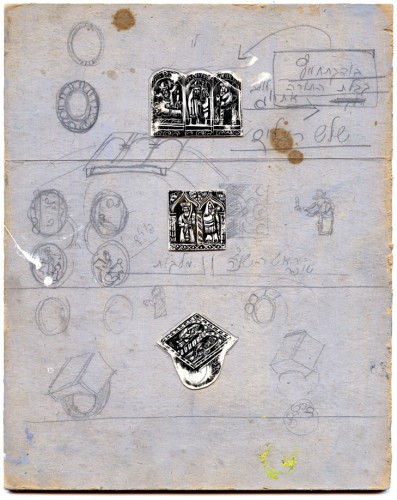

Ilya Schor, pencil sketches and scratch-board maquettes for jewelry, on board, verso of Woman Reading, mid-1940s.

A few of these works were done in Marseilles where my parents, having fled Paris in the last days of May 1940 and miraculously made their way to the South of France, waited for a visa to America.

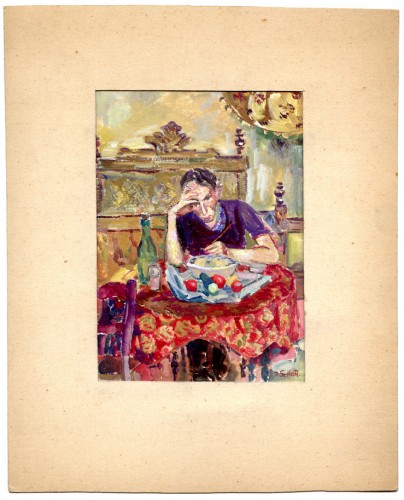

Ilya Schor, Self-Portrait in Purple shirt, gouache on paper, painted in Marseilles c.1941

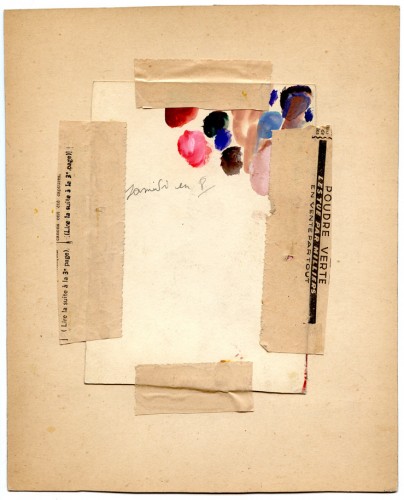

Ilya Schor, verso of Self-Portrait in Purple Shirt, painted in Marseilles, c.1941.

I can locate this work in France by the newspaper cutting that my father used on the back of the work to mount it using home made glue paste. And based on the bed represented in this work, I can be sure it was painted during that time in Marseilles.

My mother told me that when they first moved into the rooming house they were terribly afflicted by bedbugs, but after a while the bedbugs seemed to get bored with them and left them alone. Later they were able to move to a nicer room in the same building only to find themselves again assaulted by the bedbugs as newcomers to the bed in the better room.

The room seems to have had a table, and a few chairs, and not much else. My parents and their friends, musicians, painters, and other members of the intelligentsia of Europe, mostly in their late twenties and early thirties, though some older, the fortunate ones with their elderly parents in tow, spent a lot of time chasing down rumors of visas to America, often offered by countries, such as Brazil, who had no intention of letting them in but were willing with some persuasion to offer the small protection that an exit visa to another country might provide. Occasionally a friend would sleep in their bathtub because there was no place else to be found or no money to pay for a room. They wiled away the time playing cards and drinking tea, waiting for safe passage to America.

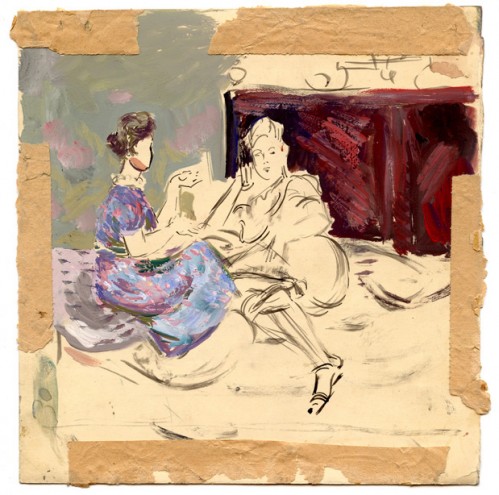

Ilya Schor, Two women in an Interior, gouache on aper, 6 3/4 x 6 3/4 inches, 1941, painted in Marseilles

Ilya Schor, verso of Two Women in an Interior, gouache on paper

Ilya Schor, Self-Portrait with Painting, 1941, small gouache on paper

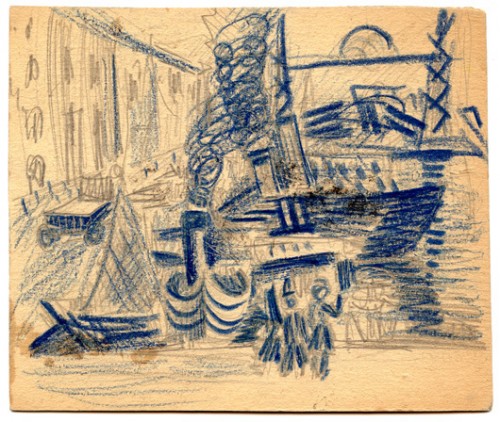

Ilya Schor, verso of Self-Portrait with Painting, pencil on paper, sketch of the Old Port of Marseilles

This spring one of my colleagues, speaking on a panel about art and politics, said that for the first time in her life she could not imagine a future, as opposed to how she had felt during the 1990s. I was very struck by this statement. I understood what she meant: things may have been bad before but at least there was some greater level of political awareness and activism that gave one a sense of purpose or hope. I think that is what she meant and if so I would agree. And yet I also thought about my parents, waiting in that room in Marseilles: in fear of their lives, with very little money and very little to eat, clinging to the edge of war-torn Europe while hoping to escape to a country they had never intended to go to, yet they had flowers and art supplies on the table, and they drew and painted, with whatever modest means. At that moment, there was no artworld. These little paintings were for the pleasure of doing them. I wonder whether this way of expressing oneself artistically when in constrained circumstance would be available to young artists today.

Ilya Schor, Still Life, gouache on paper, c. 6 3/4 x 6 3/4 inches: next to his signature my father painted the date 10 21 41 Marseille. My parents arrived in New York two days before Pearl Harbor, so working backwards through the 10 day ocean voyage, the few weeks they spent in Lisbon before embarking, and the train trip across Spain to Portugal, it would appear that my father painted this shortly before they left Marseilles.

Ilya Schor, Self-Portrait with Still Life, 1940s, gouache on board, c. 8 1/4" x 10 1/3 inches

Ilya Schor, 1940s