This blog post …what can I say? The stated goal of A Year of Positive Thinking was to write about art I love, and I love Frank Moore’s work, both the later paintings, on view in the exhibition Toxic Beauty: The Art of Frank Moore at Grey Art Gallery through December 8 and the marvelous early film Beehive which is on view at Fales Library at New York University’s Bobst Library, on the South side of Washington Square Park, on view only through Friday at 6. For some reason I was never able to pull together a sensible text about this work, so my apologies to my readers and to the work, but at this very late date, this is just to mark my admiration and urge anyone who can to go see both shows while you can. Moore’s paintings, which if they were paintings by Hieronymous Bosch or Frida Kahlo would be considered treasured masterpieces, are mostly in private collections and thus out of public view, and I hope there are ways of seeing Beehive again, it’s just joyful and great!

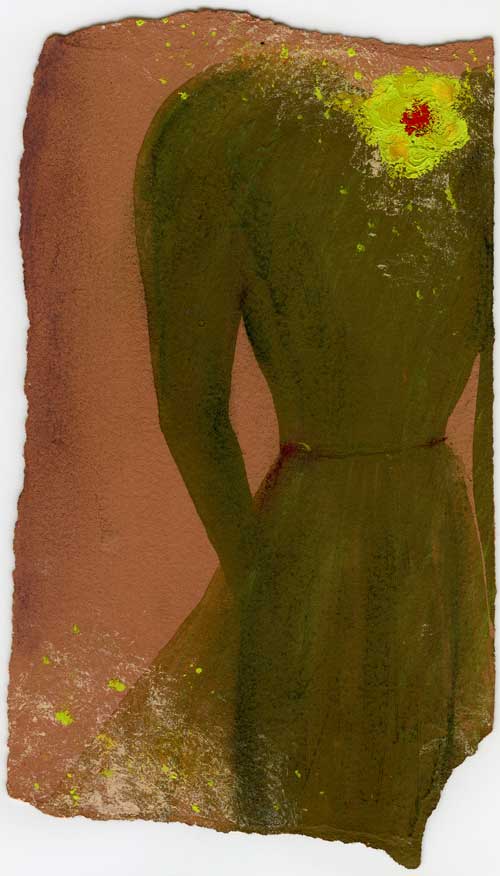

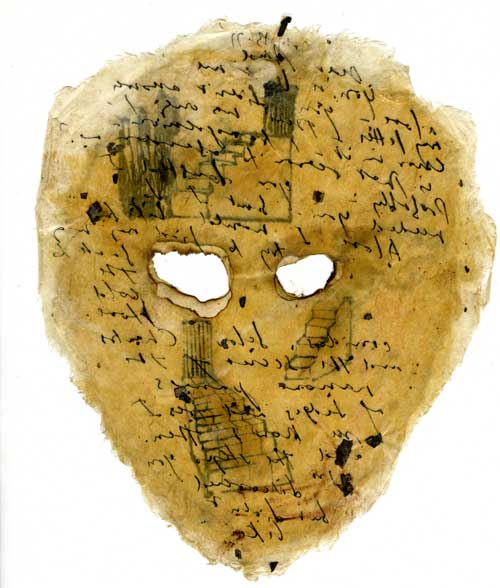

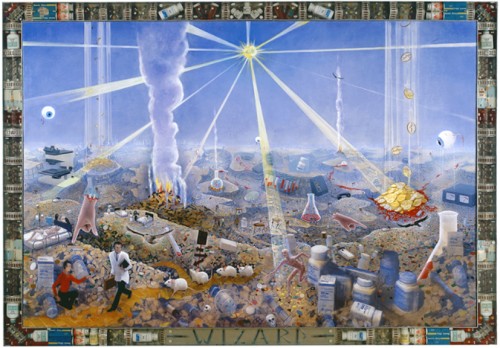

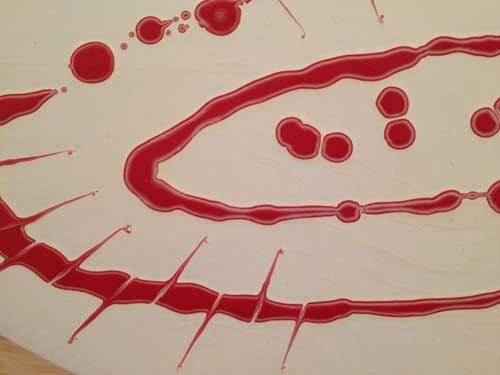

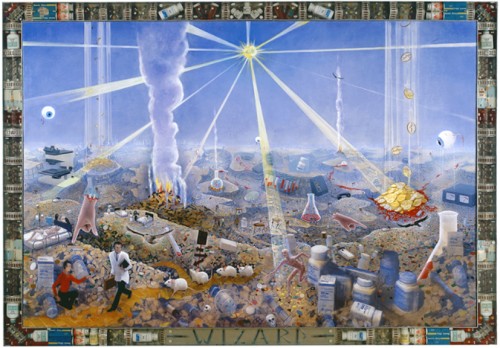

Frank Moore, detail, Wizard

This often seems like it’s a difficult moment in which to theorize painting. Or, rather, in the face of the temptations of and support for other media and methods of being an artist, young artists may still retain a longing for painting, but it is difficult to find material in support of their longing on two crucial fronts: contemporary theorization of painting, which is essential in an era in which linguistic validation is often more important than viewing artworks, and contemporary painting itself. Of course both exist: there have been significant attempts to move painting theory away from ideas still steeped in modernist discourses so that it can be seen as responsive to and participatory in the specificities of contemporary communications and there is a lot of contemporary painting including both work that is extremely successful in the art market and work which is seen to engage with more radical thought. However on any given week in which you can take students around to galleries or museums, there is no guarantee you will come across paintings that successfully enough make the dual case for painting as a practice able to address contemporary cultural issues while addressing its own medium and history.

That the narrative of the death of painting is still ongoing should be evidence at the very least of painting remaining a naggingly persistent ghost, or not even a ghost but a kind of zombie entity, not quite dead enough to go completely unmentioned. It continues to appear if only as a negative, as something that cannot be done—when a student of mine related to me what another student had told her about why painting was no longer a viable medium because it is too burdened by its history etc.. in the spirit of nihilistic humor, I took notes. At one point last spring it occurred to me to write a series of essays on the theme of When Exactly Did Painting Die? Not exactly a murder mystery, you see, not a Whodunit but rather a What Was the Time of Death mystery, or, maybe, When Was the Victim Last Seen Alive? mystery. This avenue of thought, or rather this umpteenth version of the life or death of painting argument first occurred to me as I entered the more sedate and serene uptown branch of the Armory exhibition last year, the one that is actually in the old Park Avenue Armory, and in the calm uncrowded atmosphere, from the doorway I spotted a really good late Philip Guston painting of a big fat head smoking a cigar. Well, I thought, here is evidence that painting was still alive in 1977.

You can bring the date up closer, depending on your individual taste. And of course I paint and I don’t see myself as a necrophiliac.

This is all by way of a long introduction to look at the work of an artist who instead of accepting the narrative of the death of painting, turned from performance/video to painting when the subject turned from life to death. I would be remiss if I didn’t mark in this blog the very inspiring show of Frank Moore’s work, Toxic Beauty, at the Grey Art Gallery and at the Fales Library at New York University’s Bobst Library, before it closes on December 8. Better to be last to recommend this show than never, but I feel incredibly guilty that I haven’t written about the show since I first saw it in September, and that alas even now I won’t be able to do more than suggest a few ways of thinking about the work in both parts of the show. If A year of Positive Thinking is meant to be the space where I write about artwork I love, then this is the show, I love this work, I also think it is great, so I am mortified that even at this late date just before the show closes, this is still not a polished review or essay, just a few ways of thinking of the work in the two parts of the show and a few comments rather as if I was seeing the show with you and occasionally appearing at your elbow to point to something.

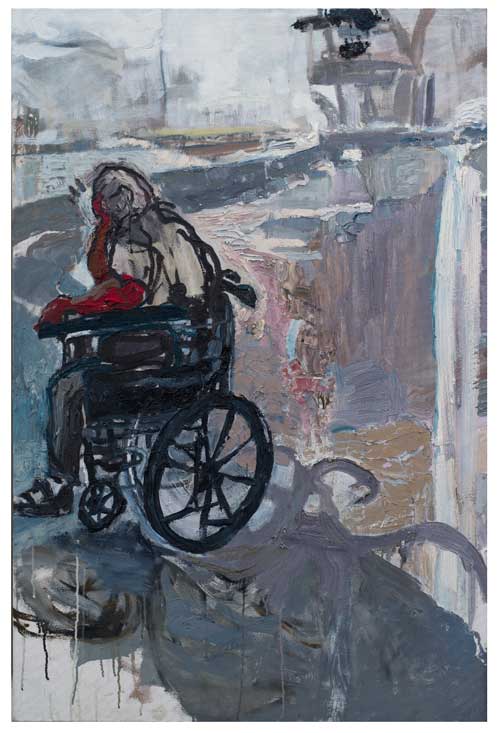

The show’s two locations each present one of these two orientations of Moore’s work. You are most likely to start at the Grey Art Gallery for reasons of accessibility from the street and location venue name, but then you will start at “the end,” with paintings Moore painted from 1985 to his death from AIDS in 2002, wherein he grapples with the face of fatal illness and the Death that ravaged a community of gay men in the ’80s and ’90s, the death of his lover, his own battle with death. Another theme of the paintings from this period is the death of a Nature ravaged by human intervention. If you start at Fales, with the earlier work, including video performance and dance, you will start with life, a joyful consideration of procreation and life. Yet to reverse the order of viewing is probably not such a good idea. Start with death, with painting as the best medium to express death. Then return to the artist’s earlier work and leave the exhibitions with life. You will be inspired by both and both media are well served by the order.

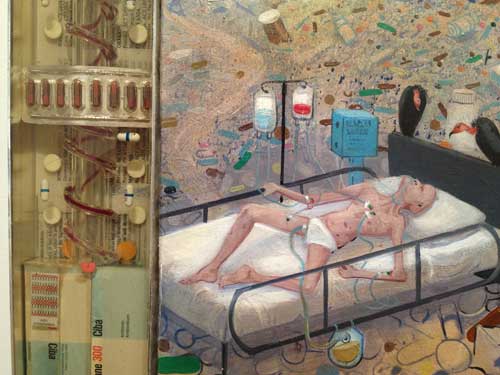

Frank Moore’s paintings are representational, figurative, with an overall approach of magic realism that places him in the general spectrum of Surrealism in a line from Hieronymous Bosch to Frida Kahlo, with a streak of folk art or regionalist art in some of the structural details including the handmade frames made specifically to develop the theme of each particular painting. Many of the paintings have ambitious narrative programs, addressing complex and highly emotionally charged subjects, in particular the countless painful and dramatic aspects of the personal, cultural and medical struggle to deal with AIDS before the development of relatively successful drug protocols. The paintings are executed mostly in a mixed technique of oil and silkscreen on linen or canvas, mounted on wood or some sort of board, very carefully painted, with extremely smooth surfaces, fine lines, and a great attention to detail. The craft of the execution is essential to point out because it is so important to see these works in person, they yield only a fraction of their impact or meaning when they are experienced only as images.

Frank Moore, Wizard, 1994, oil and silkscreen on canvas, mounted on wood, in artist’s frame (pharmaceuticals, resin, and aluminum), 68 x 95 1/2 inches–this is a large painting with exquisite surface and detail, and an awful reproduction here

- Frank Moore, Wizard, detail of painting and frame

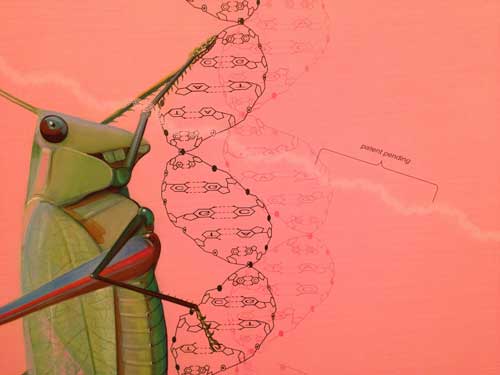

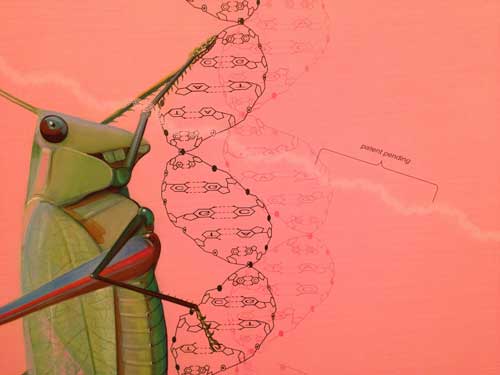

If you look extremely carefully at the surface of one of his paintings, for example, “With this ring…” (200o), a large painting with a dominant flat pink background, you may pick up ever so slight traces of canvas weave, but for the most part the surface Moore has created with great thought and care is smooth so that he can use a horizontal pink stroke with a slight differentiation of dark to light where more pigment falls from the brush. The details, an index finger at the tip of which a tiny bride reaches out to a gold wedding ring dangling from the tip of a single octopus tentacle, a fly, a gigantic grasshopper, climbing the vertical strand of a double helix, are painted with tremendous attention and care for line. So, the evocative, slightly creepy subjects amidst the brilliant color, are not the only important elements of the work. As a painter, you need sable brushes, from large filberts to single hair, good quality paint for the beautifuly surface and color, and you need to have chosen to create the painting surface so that these marks can be created and catch the light and the eye just so. You have chosen this because you love this shine, this color, this level of detail, because they reach towards the uncanny, and because they help you create an homage to notable predecessors and inspirations, Frida Kahlo, Hieronymous Bosch, Dali , who also worked with smooth surface, fine line detail, rendering, and who carry the DNA of hallucinatory magic realist representation in the service of narrativity. I may have gotten the actual materials and tools wrong in my notes before the work, but I’m not wrong in drawing attention to the details of Moore’s craft: here are his comments about this painting’s fakture:

I use a relatively limited ranges of pigments–two blues (ultramarine, phthalo), three reds (alizarin crimson, cadmium red light, phthalo rose red), five yellows (cadmium lemon, medium and dark, hansa and diarylide), two greens (permanent green light and phthalo), dioxanine purple, titanium white and ivory black. NO earth colors–I prefer to start from a point of maximum color saturation. I find the final product is more brilliant and luminous. Occasionally I will use something else like manganese blue or cobalt.

I’m a brush addict. I buy them wherever I find them. I use unorthodox brushes such as masonry and roofing brushes, wire brushes, sticks and other plant material, sponges, textiles and quite often my hands, particularly my thumb, which, for example, is evident in the stippling on the tentacle in “With This Ring…”. The marks made by unconventional tools seem to lend the work a more natural feeling, which contrasts all the more strongly with the photo-mechanical reproduction techniques I also use in the work.

Moore, “With This Ring…”, detail

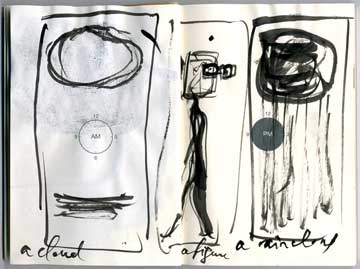

In the same interview, with Douglas Dreishpoon, reproduced in the show’s excellent catalogue, Moore also writes about the importance of drawing:

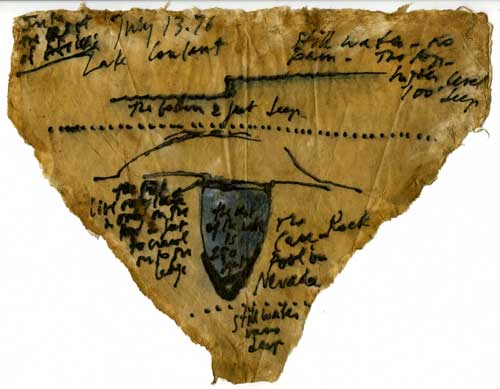

Drawing is critical. Drawing is melody. Drawing nurtures the thought, connects the mind to the page. All my images start in my mind as some kind of elusive paradox, oftentimes not even necessarily a visual one, but when I try to give it visual form it is usually with clumsy scribbles no one will ever—pure drawing.

Another thing I would point out if I were standing beside you, is that although the paintings are large in size and have such ambitious, political, narrative programs that are developed in many detailed vignettes best read from very up close up, Moore is masterful in his maneuvering of the viewer so that large abstract compositional elements and beautiful large areas of color draw you in until you are close enough that you begin to perceive the detail and be captured and captivated into an entirely different type of reading. This is the case in Oz for example, a painting I still remember seeing when it was first shown in New York City at Sperone Westwater Gallery. Oz (1999-2000) is a kind of encyclopedic landscape of catastrophic environmental mayhem, a genetically engineered beanstalk shoots up from a pot of gold coins while individual families relax, play golf or the piano, and lie on rubbish piles of their destroyed homes. The painting’s theme makes even more sense to me than when I first saw it when it was originally shown at Sperone and thought about how strange it was to have this intricate painting about genetically engineered corn. Today the damage wrought by genetically programmed agribusiness and the image of destroyed suburban life is much more part of our knowledge and image bank than it was even fifteen years ago, when it was made and when it seemed like a bit of an esoteric though unforgettable direction. Moore might have appreciated, in a dark way, the facts and the imagery of a recent story on NPR about how little natural life exists in an average Iowa cornfield as compared to plots of land in other areas of the world.

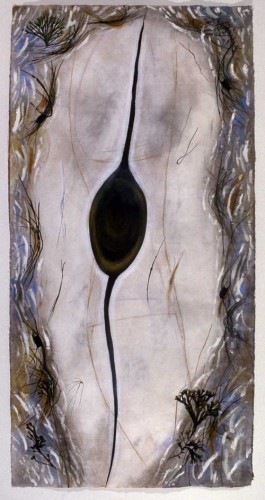

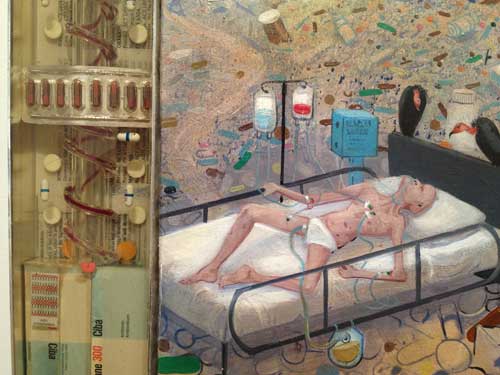

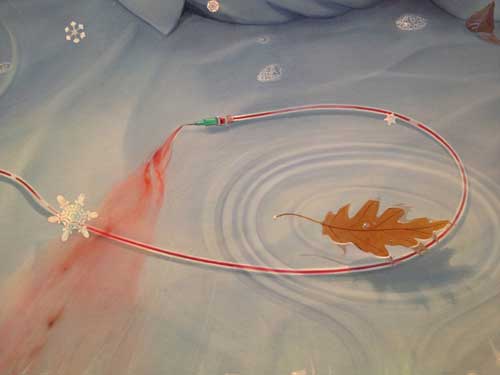

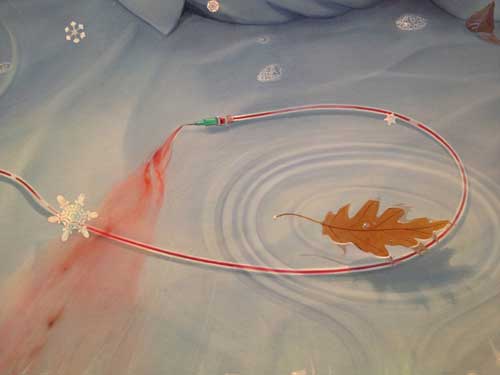

Many of the paintings deal directly with the trappings of illness, medications, IV lines, blood, cancerous lesions. In Patient (1997-1998) blood seeps from an open IV line onto a bed, which, painted an icy blue, seems to be a melting pool of ice water instead of a zone of comfort. In one detail you have the smooth blue precision of the sheets, painted bubbles of water or foam and silkscreened white snow fakes (thus actual patterns, not invented ones), there is no direct figuration, not necessary, but there’s as much about mortality and evanescence than if the leaking bleeding body in pain was present.

Frank Moore, Patient, 1997-98, oil and silkscreen on canvas mounted on wood, in artist’s frame (red pine) 49 1/2x 65 1/2 x3 1/2 inches, detail

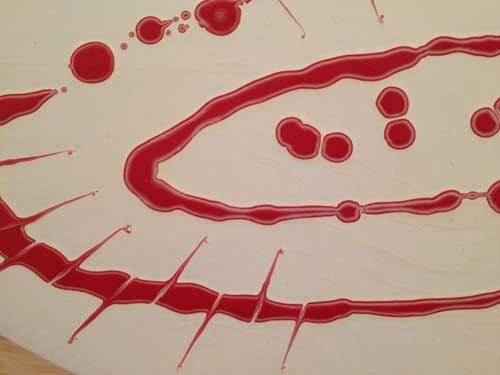

There was one painting of Moore’s that I particularly held in my memory since I first saw it at Sperone years ago, because it was so inventively expressive especially considering the simplicity and economy of its subject in comparison to the impressive larger works like Wizard.

Blood seeps out of two slices into a loaf of bread and into the middle of a puddle of spilled heavy cream which has oozed out from an overturned cartoon. The red paint has been dropped into the pool of white paint to create a very careful Jackson Pollock in the shape of a Crown of Thorns. The Christ reference and the art reference are at the center of a still-life painting with an almost folk art sensibility: the dusting of flour on the loaf of bread is created with a kind of spray effect which is completely different in technical feel than the loaf, or the cream and blood spill. It’s a folk Zurbaran of the AIDS era.

Frank Moore, Easter, 1994. Oil on canvas, 20 1/4 x 27 1/8 inches.

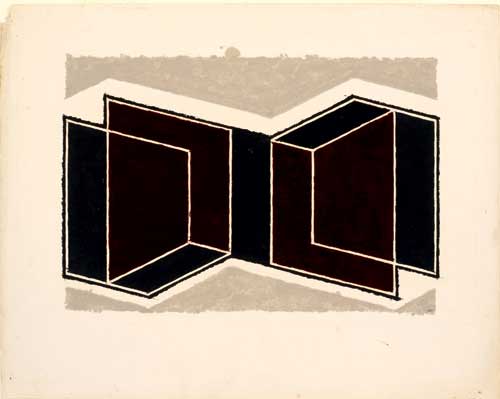

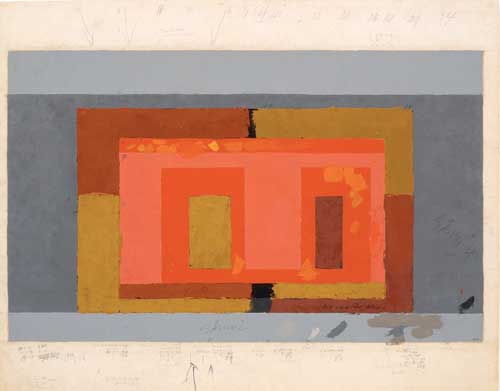

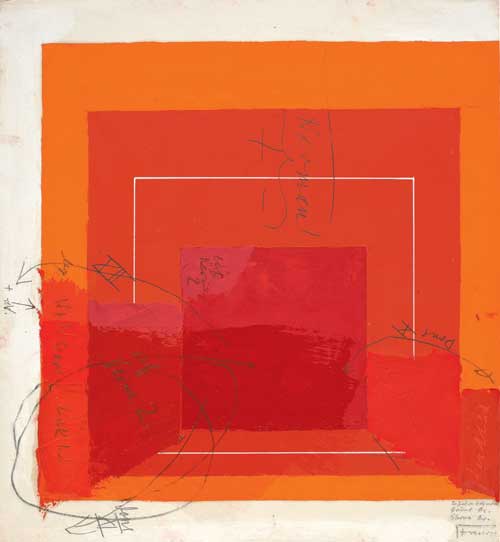

* At the Fales Collection, the works on view include some of Moore’s many sketch books and two filmed collaborative dance and theater and performances, The Miller’s Wife (1987) and Beehive (1985) along with the story board drawings for these. The Fales section of the show is only open on weekdays so there are only three more days to see it, but all I can say is, Beehive, which Moore created with choreographer Jim Self, is one of the most beautiful and joyous works I’ve ever seen. Its subject, procreation of the bumblebee, is entirely oriented towards life, and its style is absolutely the opposite of the paintings: big bold primary colors, yellow, red, blue, orange, black and white. The forms are also bold, the music is great, lilting, funny, silly, joyful, driving, with sound effects, “dialogue” something like the “uh oh” of the Teletubbies or like funny sound effects from the 1920s and early television but put through an electronic filter and always upbeat and beautiful. Here the artistic resonances are not with Hieronymous Bosch but rather with Diaghilev and Matisse, and with the sets an ’80s Pop version of a German expressionist movie. The angles of the spaces may be related to German Expressionism but the color is more Russian vanguard modernism, or folkloric a la Diaghilev with an overlay of ’60s pop feel.

Beehive is quite addictively magical and gorgeous. Death is not here, it does not shadow this work at all, just beauty, joy and pleasure through sound color, movement.

The one element which is the same in both groups of work–this film and the paintings–is that, even though the overall appearance and style are different, each gesture and frame is exquisitely thought out and executed in detail, even if in the film the details are bold, bright, and joyful, rather than finely detailed and horrific as they are in the paintings. Nothing is amateurish, there is no DIY , no camp, and yet the style is not commercial either.

In Beehive nature is good, in paintings like Oz nature is damaged by human intervention, it has beauty but that beauty is toxic.

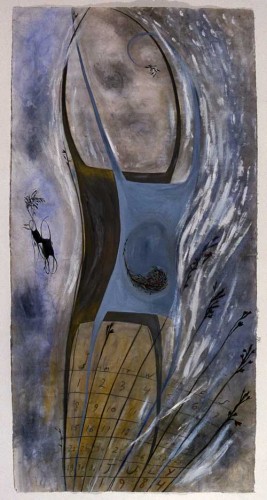

Frank Moore, Formal Garden, 1985, Oil and felt-tip pen on canvas, in artist’s frame (wood), 26 x 104 1/2 inches

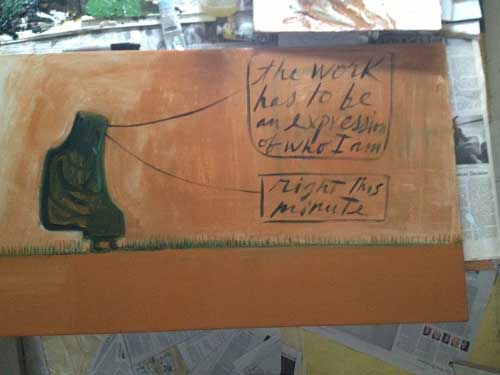

One of the first paintings you see at Grey Art Gallery, Formal Garden, is, in its forms and spirit, more like Beehive than like any of the other paintings in the show. A horizontally oriented painting with a rustic wood frame made by the artist, it represents boldly drawn shapes, a bird, a phallus, an elephant all seem to burst from roots in dark earth up into blue sky above: the chimeras caused by man’s intervention in nature are still exuberant and slightly folk inspired forms. This painting is from 1985. Moore was diagnosed as HIV Positive in 1987. In a late interview with Robert Atkins on the AIDS-Arts Forum Artist in the Archive series, Moore suggests various artistic and also practical reasons reason for his change of focus from dance and performance to painting,

Theater work is great because it forces you to make instantly comprehensible gestures, there’s not a lot of time to ponder ambiguity or you risk losing the audience. As [artist] Thomas Woodruff says, the problem with subtlety is that nobody notices. I also liked the communal nature of theater, the family value. But there’s also a downside. You are often under a lot of pressure, there are constant deadlines and people are depending on you. Theater is also much more expensive to produce than painting, what with salaries, space rental, and the like. Also, unlike a painting, theater is ephemeral. Another factor that really pushed me out of theater was the long illness of my lover Robert Fulps. I had to be at home.

It is tempting to take that further and see not only the turn towards painting but also the change in the style and narrative direction of the work after 1987, as the best medium for Moore to develop a complex, detailed, crafted visual language for the subject matter he now felt the necessity to address.

Frank Moore is a major artist and yet his name and work are less well known than other artists of his generation who also died of AIDS, including Keith Haring and David Wojnarowitz. There are always many factors in what happens to an artist’s reputation when that artist dies too young, before they can do everything they can for themselves in their life time. Since his estate is represented by an important gallery, Sperone Westwater, it is hard not to presume that his relative obscurity (with passionate admirers and fans of course) is due to the fact that his work is composed in part of large narrative paintings of formal complexity representing the dark side of American life and death in a painting language that is by turns familiar, seductive, beautiful, but also does always not give us a quick and easy read. And these are paintings that are best seen in person, because their craft and their sculptural presence is so important. And, further, the major paintings are in private collections so not readily available for public view and study. I can only hope that the owners of Oz, Wizard and other major paintings from this particular series see their way to donating these paintings to New York museums, hopefully several of them to the same institution. I vote for their being able to be compared and contrasted with the works of Florine Stettheimer, so, New York museums, the game is on.

Or, anyway, in terms of my murder investigation, Painting, What was the Time of Death? “Toxic Beauty” assures us that painting was still alive in 1994 when Moore painted Wizard, and in 2000 when Moore painted Oz. That’s not that long ago.

Painting: the undeadness continues.