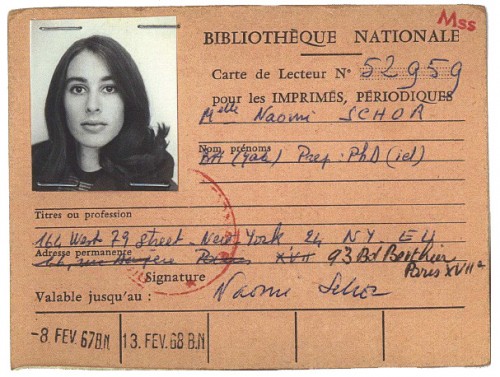

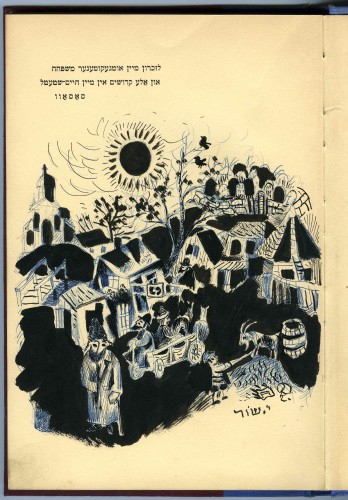

Today October 10, 2012 would be my sister Naomi Schor‘s sixty-ninth birthday.

I always like to mark her birthday in some way. This year, my birthday remembrance is about politics and newspapers. We shared a passionate, anxious, and affective relationship to politics, something we had both inherited, I believe, from our parents, whose lives had been affected by major political catastrophes and who had an interest in history and politics. One of the interests we shared was in the American electoral process. We enjoyed the theater of it, shared what we felt were the high points and agonized over the darker moments in the years we experienced them together. I know she would be completely wrapped up in the current election, as I am, and perhaps prey to the same moments of deep anxiety about the future.

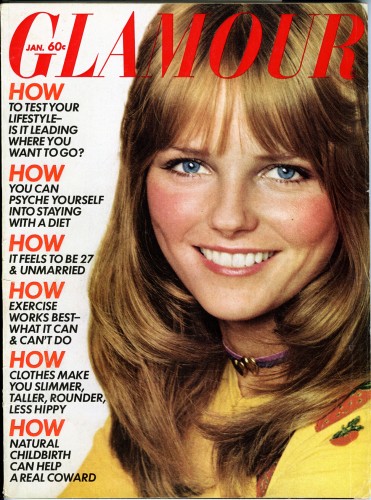

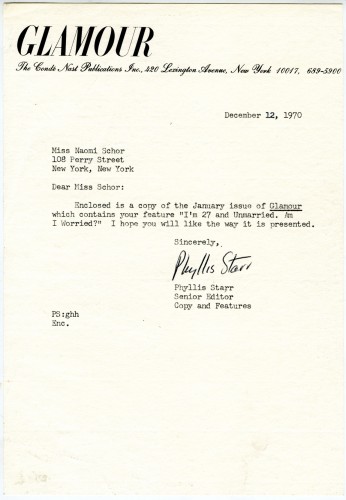

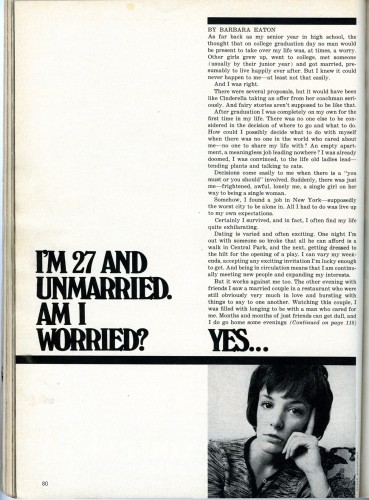

Last week I went through a box of newspapers and magazines she had saved over the years and had taken the trouble to pack up and take with her for each of the several moves of her distinguished professional life. I too save copies of the paper and in some cases I suspect I have exactly the same material packed away in some box of my own. I photographed each publication in the box so that I would have some record of even those I was able to force myself to throw out, saving a few as possible research material for an approach to writing about her, part of my larger and still very germinal project of writing a cultural autobiography that, at this point, is more focused on keeping the life and work of my parents and my sister alive as long I can, not just for myself, but for what I think they can mean for anyone else.

The contents of the box I went through included several example of coverage of Watergate.

The date on this newspaper is August 8, 1974, though the Wikipedia timeline states that Nixon resigned on August 9th. The resignation was announced on the 8th, and was official on the 9th when President Ford was sworn in.

Here are two other editions of the New York Times, from Wednesday, July 31, 1974 and Tuesday, August 6, 1974, as the final stages of the Watergate scandal played out across the print press and television coverage that had gripped much of the country. For myself, I had been at graduate school at CalArts in the early stages of the scandal, and I think this may have been the one point in my life I was not reading the Times regularly or particularly focused on anything except my own life: I was absorbed in new friendships, in the first class I ever taught, and was preparing my MFA show. The Senate Watergate hearings had begun May 17. When I got back to New York around the 3rd of June, 1973, Watergate was all anyone could talk about, I found that my mother and sister were obsessed with every development so I got up to speed and I watched every minute of the Senate hearings from that point on.

The first of the two copies of the Times that I had set aside, in a kind of hoarder’s purgatory, not safely back in the box for further research, not in the bunch I actually did throw out, is from two days before Nixon resigned:

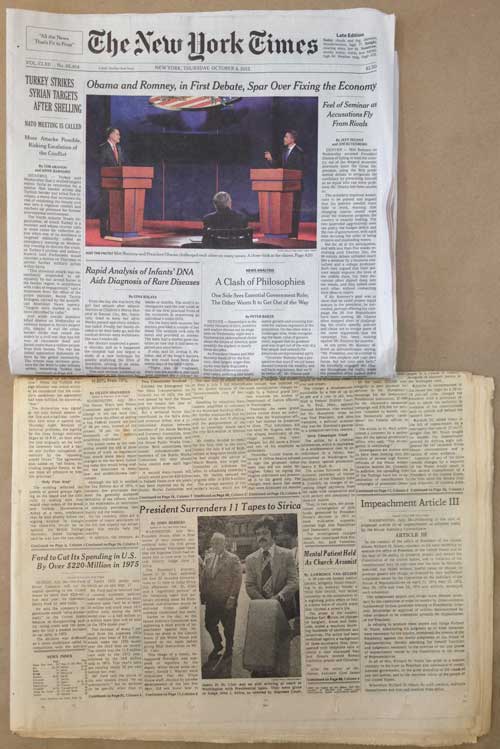

The other edition I selected is from a few days before that, July 31: I was about to throw both of these copies out and just hold on to “Nixon Resigns” but when I put a current paper on top, also to be discarded, I was struck by the physical difference in size between the paper then and now:

The first thing that one notes in handling the historical copies and the paper today is that it has shrunk considerably, I believe the size has been diminished twice in the past twenty years. The 1974 paper was 23″x14½,” the current one is 22″x12″–not a huge difference but a less imposing artifact to be sure and it appears much narrower when placed next to or on top of the old version. When the newspaper last shrunk, I recall that readers were assured that the percentage of news coverage would not diminish: I remember counting the news stories in pre- and post- shrinkage editions–can’t be sure but I think that I found that, contrary to that claim, there were in fact slightly fewer news stories.

Most people would agree that this more modest scale is ecologically sound, and at this point I am just grateful I can still begin my day reading the New York Times in hard copy though diminished not just in dimensions but in amount of pages, and perhaps also in amount of news covered of a non-entertainment nature. It’s not perfect, but it is still the newspaper. One of my sister’s friends says that the one reason she doesn’t mind getting older is that she may possibly not outlive the hard copy publication of the New York Times! Nevertheless, to hold the 1974 issue is an experience with some gravitas that is perhaps lacking today. OK, already you can see the disjunction here: gravitas and news!!! I just watched The Daily Show tonight. Like a lot of people I count on Jon Stewart, a comedian, to do the job mainstream media reporters as well as sitting presidents should be doing in mano a mano combat with Republican bullshit, so that portentous experience of holding open in your hands that 46 inch full spread of 8 columns a page of news is a long long time ago.

Looking at the paper from last week’s coverage of the first Presidential debate between President Obama and Mitt Romney, the situation seems more depressing and more dire than the situation in 1974, because the peculiar thing about the Watergate scandal is that at the same time as it uncovered a plot by the President of the United States to subvert major branches of government and that it made us acquainted with some horrible people, including a close-up view of the dark soul of Richard Nixon, it also introduced us to some politicians one felt one could respect and admire, and revealed courage, integrity, and what could still seem like authentic authenticity at many levels of American culture from the press to the government. There were as many heroes as villains in the story and as I recall there was some level of continued trust in America despite everything that was revealed during the process. “The system worked,” or so people said at the time.

But things were happening in that very moment of the seeming triumph of justice and democracy that have a bearing on our own time. The stories are more linked that one might think. The 30+ year reign of increasingly right wing social politics and corporation friendly laws and Supreme Court decisions we have endured since the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980 actually began during the same period as the most vivid moments of political fervor and transformation of the 1960s, and a return to order was already being formulated during the Nixon administration. For example, the so-called “Powell Memo” or Powell Manifesto was first published in August 1971, as “Confidential Memorandum: Attack of American Free Enterprise System.” In it, then corporate lawyer Lewis F. Powell laid out most of the political goals and tactics for the right wing, calling for the creation of many of the institutions that have brought us to decisions like Citizens United and organizations like ALEC. Powell was named to the Supreme Court by Nixon two months after the publication of this document. In another example of the links between then and now, one of the few figures who did not show backbone and political heroism in the events known at the “Saturday Night Massacre,” when Nixon called for the dismissal of Watergate independent prosecutor Archibald Cox by executive order was then Solicitor General Robert Bork. Later rejected by the Senate when he was nominated to the Supreme Court by Ronald Reagan, Bork set the model for Justices like Antonin Scalia and is said to be advising the Romney campaign on Supreme Court nominations should Romney be elected.

Yesterday I spit into the wind and wrote to President Obama at “Letters to Obama:”

Dear President Obama: I hope you will fight back and fight for this election, against lies and to prevent what I think would be an incredibly dangerous President and Vice President, with Republican majority. Is this the country and the world that you want for your daughters to live in? This election is not about you indeed, it is about us, we can vote, yes, your loyal though often frustrated base will vote for you, but you are the only person on the stage who can fight back against Romney’s shape shifting lies, we can’t. So, at long last, do it..you don’t have to overact at the next debates, you just have to defend your record, your beliefs, your policies, and the truth. The country’s fate is at stake, not just your career.

Sincerely,

Mira Schor

Utterly futile and a lot more polite than what I really want to say but perhaps just a little birthday card to my sister, who would have despaired of a Romney Presidency, as do I.

*

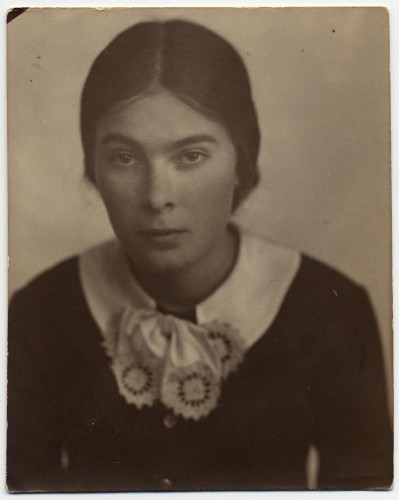

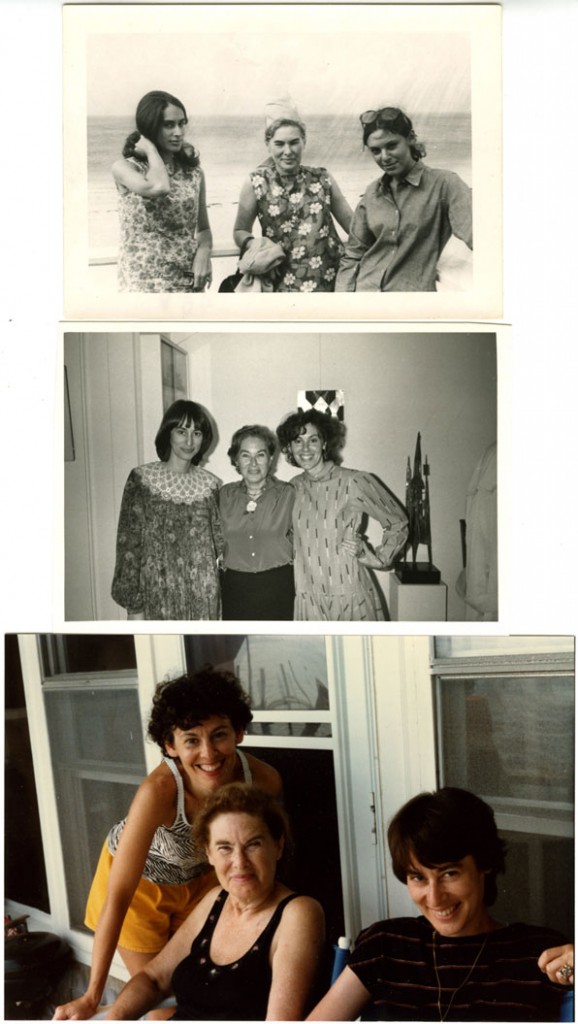

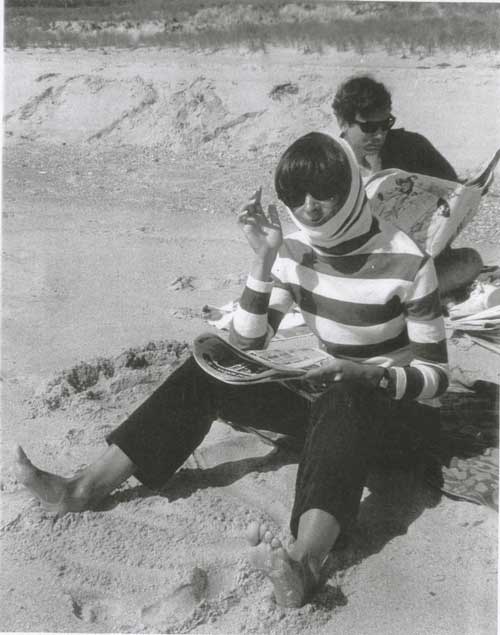

My sister and a friend, reading the newspaper on the beach, late 60s or early 70s.