I like it when someone asks me a question on something I might not ordinarily think about or write about: I can’t help but start to wrap my mind around it and I may even get so involved that I answer at length when brevity might have made more sense. A case in point: last week I received a Facebook message from someone I didn’t know (not even a FB friend at the time) asking me if I would answer some questions about the contemporary art museum. I didn’t know whether he had read my recent blog post Intimacy and Spectacle 1 though his message did come a couple of days after that was published. But I was intrigued because issues raised by MoMA’s recently announced building plans have been on my mind, so I answered his message and I received the following questions under the rubric “Questions about (contemporary) art museums – Dissertation of Cultural Management / Portugal” from Juan Gonçalves who is working on a dissertation developed within the MA in Cultural Management from the University of Madeira, UMa, 2013-2014. Once I started answering his questions I got so carried away that I thought I might as well share the letter on my blog, which Juan agreed to, since he can quote from the blog in his dissertation. I don’t know much about the program he is working and I have not been to Portugal so my response is lacking a sense of his context.

These were his questions:

1.The definition of a contemporary art museum is still valid? Would you suggest another?

2.How to break the barriers that still impose the museums of contemporary art and its audience?

3.How the contemporary museology works in this economic crisis?

4.What is the best architecture for a contemporary art museum?

5.What can you say about contemporary art museums in Portugal? And about the artists?

Here are my answers:

Dear Juan Gonçalves,

Thanks for asking my opinion on questions about the contemporary art museum. I am not an expert in museology so I am speaking primarily as an artist though also as an educator, and art writer. My opinions are principally coming from my own desire to be able to see art so that I can really see it—I was going to say to experience it but that word “experience” already gets into the spectacle or entertainment regime that museums are increasingly obsessed with.

1.The definition of a contemporary art museum is still valid? Would you suggest another?

I don’t think much about it: I’m more concerned with what is in a museum than what its name is but I have accepted the nomenclature of contemporary art museum. I do want to see contemporary art or new art, and a so-called museum of contemporary art is a place in which to see what some people think is going on, but the academic/corporate category contemporary art doesn’t interest me that much, even though I consider myself a contemporary artist.

As it is frequently noted, contemporary art is a contradictory or oxymoronic category. Nothing remains contemporary and even to define what is contemporary art is difficult—the essays in e-flux journal’s 2010 book What Is Contemporary Art? ended up more haunted by modernism than definitive about the character of the contemporary. Is all art made today–thus, literally, contemporary–considered suitable to be shown in museums of contemporary art? No. We know that most art being made today will not be shown in museums of contemporary art because certain determinations have been about what is contemporary: usually new media and technology, theater, spectacle, and participation, as well as a focus on young artists and responsibilities to the global.

One goes to a contemporary art museum to learn about the contemporary moment, what the art selected by a defined international academic/corporate cadre will tell us about the world we live in, for better or worse. Whatever is considered contemporary art by the contemporary art museum is cultural utterance of interest although what the work exhibited actually says about this particular historical moment may not be as evident to us in the present moment as we think, because, as suggested by Walter Benjamin, the artwork contains “unintentional truth” about the present that is so much part of our ideological frame that it is invisible to us but its trace will become transparent over time. Whether it is “truth,” which would sound absolute and unchangeable, is not as relevant as the fact that another truth about the contemporary art work will be visible in it as time passes and the work is no longer contemporary. One problem is that the contemporary art museum is principally meant to define the present to the present but it ends up writing art history, so much from a time period may be lost because a narrow cadre left it out. That is a problem because the pressure of being contemporary allows no time for things to sort themselves out, for the sediment to fall to the bottom of the test tube. I should note that our particular contemporary seems particularly uninterested in time, in history either looking back or looking forward–but maybe people were already saying things like that in 1850! In any case artists, curators, and museum directors can only do what they can do or see what they can see at a moment in time based on knowledge and motives specific to that time.

Because of the nature of the newness of contemporary art there is the problem of where commercial galleries’ role ends and contemporary art museums’ roles begin. But it is interesting for a museum to try to keep up with and try to define and present the contemporary at any given moment. And it can be useful to the viewer with some experience in art if this kind of investigation takes place in a museum with some sort of institutional history that gives the curatorial choices a context. My memory goes back to some of the early Projects exhibitions and the Information show at MoMA, which had a stronger impact from appearing in the context of canonical modernism. So perhaps the museum of contemporary art is too limited a situation, the contemporary makes more sense and is more exciting if seen in the context of the past.

In terms of a category of museum of contemporary art, the model of the Kunsthalle without permanent collection is a good one also, in addition to the more conventional modern/contemporary museum. I think it is important to have both kinds of institutions. In the United States we don’t seem to have that much of a Kunsthalle culture though the New Museum functions that way here in New York and there are a few other institutions like that around the country. smaller centers of contemporary art often have the freedom to put together more heterodox and imaginative visions of the present because pressures of the market don’t totally penetrate the local. I think it is great to have that kind of institution as well as larger museums with a mix of permanent collection and special exhibitions.

2.How to break the barriers that still impose the museums of contemporary art and its audience?

All museums today, not only specifically museums of contemporary art, are interested in attracting large audiences mostly for commercial, economic reasons. That is true if they are private institutions or supported by the state. On Wikipedia’s entry for museology there is a section on “Tourism as a vehicle for success.” Any art of any time period can be of interest to any audience, I am convinced of it, so long as there is access, financially and through education programs. It is not necessary to pander to “the audience.” But museums and in particular contemporary art museums are now thinking about audience mostly in terms of traffic flow, how many people can be cycled through the galleries to the restaurant and the gift shop. They give that basic commercial desire a theoretical or political gloss by talking about the “audience” the way leftists might speak about “the people.” There is genuine idealism in institutional educational outreach programs, most museums offer fantastic resources for the community although there is still a huge gap between a general audience which might find any art museum an intimidating place but as older museums showing a range of art including but not limited to the contemporary probably do just as well as contemporary museums in attracting culturally and economically diverse audiences. Even if you add all the features that you think will attract a younger audience, you still are dealing primarily with a privileged audience. The museum is still intimidating, it takes more to make less privileged audiences feel welcome and able to take advantage of opportunities for access the museum may offer. This past summer the New York Times published a story about a young woman who hung out in the lobby of the Brooklyn Museum because it was air conditioned. She became interested in the one art work she could see for free from her vantage point, Kehinde Wiley’s Napoleon Leading the Army Over the Alps. She didn’t venture any further because she couldn’t afford the admission fee until finally a friend told her that it was only a suggested fee.

To get the most traffic flow, it seems to be desirable to design museums and curate shows that will function as good backdrops for selfies. The so-called “experience economy” is not only predicated on giving people thrills of some kind, but also and perhaps even more on giving people something which is actually the opposite of what I consider an experience of art, it is the experience of taking pictures of yourself in front of something, the art is a ready made set for your photo-op. Some of those “backdrops” (the art and the architecture) are terrific, and it’s Pavlovian, I get sucked into the selfie regime as quickly as the next person: I have a whole collection of self-portraits taken in contemporary artworks made of shiny reflective material. Maybe that emphasis on self within spectacle is one characteristic of contemporary art.

Self-portrait with Susan Bee, Armory Fair, 2010

Self-Portrait with Susan Bee, Armory Fair, 2012

You get the picture. One had gone from a slightly discredited art historical model of the work of art as reflection of society to contemporary art as an actual reflective surface in which the viewer can see herself.

But I am happiest when I can wander through a quiet, elegant, even modest museum that makes it possible for me to have a meaningful interaction with an artwork, even just one real experience of seeing is enough, in a day. I need to hear myself think, even if I am in a crowded space. This may sound old fashioned and art object oriented but in my capacity as a teacher, I have noticed how hard it is for my students to actually see the art in museums — I guess here I do mean painting and sculpture and objects— how hard it is even to really focus on more spectacular video installations, not that they can’t, they may respond more immediately to such installations which are more accessible to them, but they may also just be sitting down so they can check their email. This can lead to cynicism and alienation in a demographic that is paradoxically the presumed principal target of the contemporary museum of contemporary art, under the guise of a fun-house atmosphere aimed at pleasing just that demographic. Everyone feels the loss of human scale, the difference between my generation is that perhaps we can pinpoint the reason we feel a certain way within these new spaces because we did have experiences of human scale within museums of contemporary art: the Pasadena Art Museum in the 70s was such a place, for example, and, of course, the much mourned Museum of Modern Art in NY pre-1983 and pre-2006. Your questions came just at a moment when it occurs to me that most of my students have only experienced the 2006 version and when we (people born before 1980) express our dismay about a type of museum experience and a type of relation to art that we feel is lost, they basically can have no idea what we are talking about.

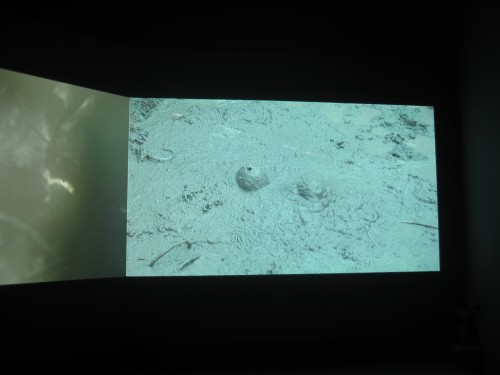

(images above from Isaac Julien, Ten Thousand Waves, MoMA, 2013)

Curiously some of the commercial galleries that represent the apotheosis of the contemporary art industry and market, such as, here in NY, Gagosian and Zwirner, have been able to mount museum quality shows the past few years, including for example excellent Picasso and Frankenthaler exhibitions at Gagosian and the recent exhibition of Ad Reinhardt’s work at Zwirner, in spaces that either are as beautiful as any museum or that are just functional in a good way, with few frills, just good walls and space. Because their financial motivation is on another level than who walks in the door to see the work, they don’t have to try to attract the entertainment-seeking “audience” since the real business is taking place elsewhere. And, although galleries may seem even more elitist than museums, actually these shows are free, there is no admission price at all.

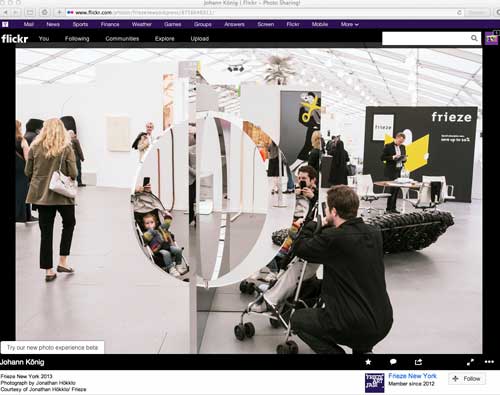

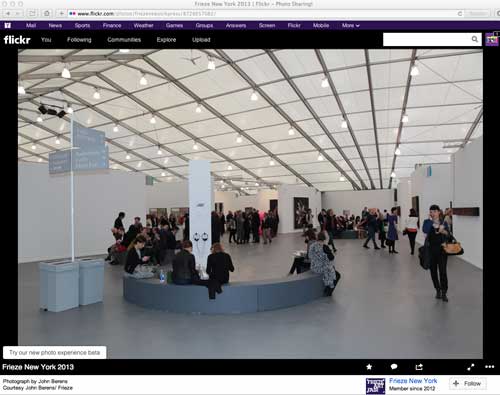

The reverse example might be the international art fair, for example Frieze’s fair on Randall’s Island in New York, a kind of upscale Shangri-La of contemporary art seen from the point of view of the market, which, some might argue, is contemporary art. In fact the Frieze fair model is really a perfect manifestation of a contemporary art museum: it is open about being a function of the art market, works must compete instantaneously with a very wide though certainly not comprehensive selection of contemporary art made around the world, the designers make an effort to give smaller works some space but it is busy and there is a tendency for art which is large, shiny, or in some other way spectacular and photogenic to do particularly well. And the whole thing is not just contemporary but temporary, which really makes it a representative instance of the contemporary.

But many of these newly built contemporary art museums are designed so that they will accommodate large installations and events and that scale will then influence the production of future contemporary art that will tend to the large, the spectacular, the entertaining because those are the modes that will function best spatially and as images. Such spaces are less likely to nurture or support more intimate work and also experimental work including art of social engagement which seeks to engage with the world outside the walls of the elite institution.

So, as you can tell, contemporary art museum or any art museum as fun house for the Google iPhone generation is not my favorite, or, it is fine, so long as beautiful museums are not destroyed in order to achieve those goals. As you know, currently New Yorkers are upset about MoMA’s plans to put the last nail in the coffin of what was one of the most meaningful art experiences. The response to their new plan on the part of artists, architects, architectural critics is hatred and contempt, rage and mourning. Most of us already disliked the Taniguchi remake so much we didn’t expect it could get any worse.

3.How does contemporary museology work in this economic crisis?

The current economic crisis of course makes it all the more tempting for museums to try to make themselves desirable to a tourist audience and to people who are interested in the museum as just another glamorous fun place to hang out and take pictures, where art is peripheral and everything leads to the gift shop. It also makes museums more vulnerable to the machinations of their board members.

4.What is the best architecture for a contemporary art museum?

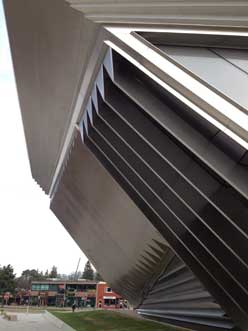

I enjoy museums with spectacular architectural designs, as art objects in themselves. But it is amazing how egotistical these spaces can be when it comes to accommodating the art works they are supposed to present. I recently visited Zaha Hadid’s Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum in East Lansing, Michigan: it is really beautiful both outside and inside, like a gleaming silver spaceship that happens to have touched down in a college town on the flat plains of the American mid-West. However most of the interior exhibition walls are at an angle, which in some spots induces vertigo, and which makes it a pretty eccentric place to look at painting, drawing and photography, not terrible, in some cases works actually look interesting, but they definitely have to struggle with the situation. Maybe that is part of the point of the design.

On the other hand a recent visit to the new updated Yale University Art Gallery is exemplary of a wonderful museum experience, where you feel like a human being, and can explore wonderful artworks in spaces that are beautiful and functional without being ostentatious and where there are shifts in scale and intimacy between small and eccentric old spaces and larger white cube spaces depending on the needs of the work. It adapts architecture from different eras and styles and I think that is a good model. And it is free which is a fantastic gift to the public.

In general, it seems that older spaces that have some history, including repurposed spaces previously used for industry or commerce, often make good spaces in which to exhibit contemporary art. MoMA Ps1, in a former public school building in Queens, NY is a good example: dimensions and characteristics of the exhibitions spaces vary in eccentric but very useful ways that allow for a variety of types of art, and the initial decision to maintain those basic dimensions spared us from contemporary architectural decisions that might be detrimentally egotistical or trendy in scale or pretension. Significantly in recent years some of the best exhibitions offered under the aegis of MoMA have taken place at PS1 because of the intimacy and character of the rooms. The DIA building in Chelsea was also an effective model of a space that was not new, was fairly simple, had a human scale, and got out of your way so you could concentrate on the work.

I think a museum should offer some moments of visual pleasure, small architectural details or sweeping vistas that are pleasurable, beautiful, with attention to natural light and structural materials, elements that show that thought has been given to offering a sense of pleasure to the human being, thinking has gone into human scale, not just architectural vanity, corporate scale, and entertainment value. As Barnett Newman famously said in Emile de Antonio‘s film Painters Painting, “in the end size doesn’t count…it’s scale that counts, it’s human scale that counts.” He was talking about painting, but the shoe fits for architecture too. Architectural pleasure for the sake of the architecture should be paired with the architecture being able to get out of the way of the artwork in it and let you see the work as if it belonged entirely to you only, for at least a moment in time.

5.What can you say about contemporary art museums in Portugal? And about the artists?

Unfortunately I have not had the pleasure of visiting Portugal so I cannot comment on museums in Portugal.

Sincerely,

Mira Schor

FYI, This post is not a promise that anyone who writes to me should expect a response, short or long, or that I will publish that response on A Year of Positive Thinking.

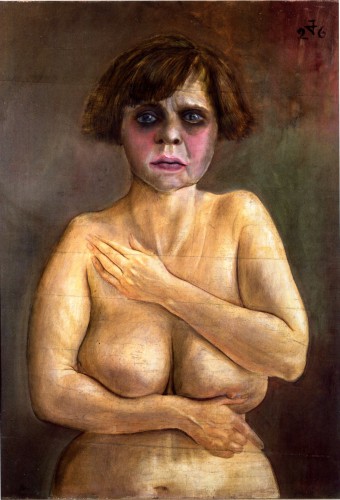

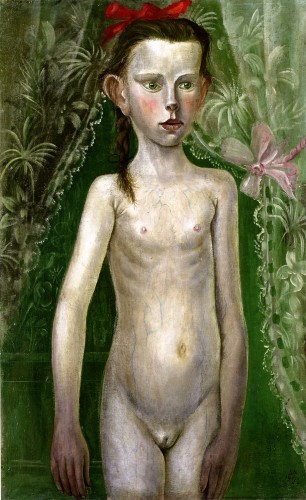

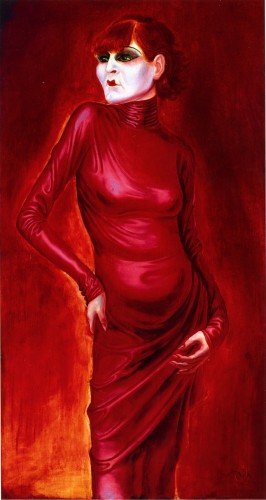

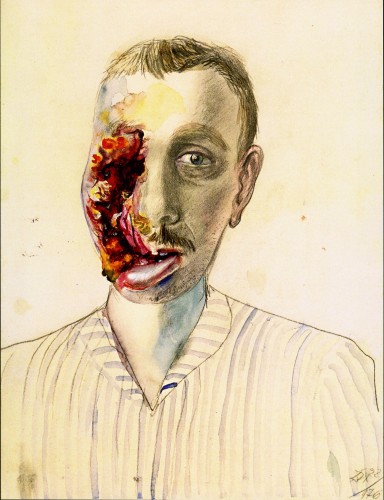

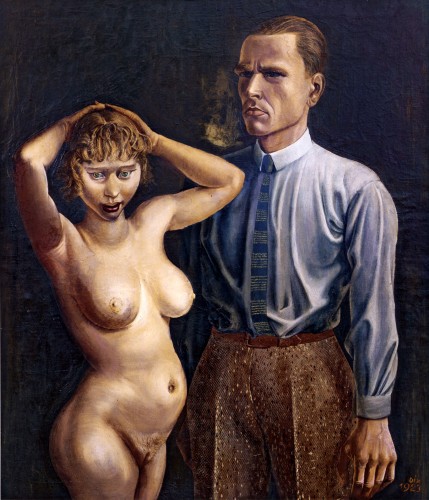

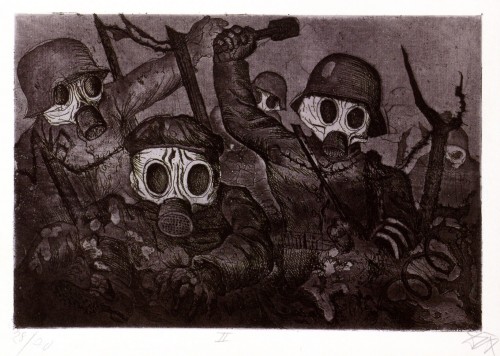

Despite the disturbing violence depicted in these works, I find in many of Dix’s paintings of women something other than misogyny: the humanity of the women is never sugar coated into pneumatic attractiveness in the vein of John Currin, who Dunham mentions in regard to Dix’s sources in Northern Renaissance Germanic and Netherlandish portraiture. To the contrary, Dix adopts the detailed, delicate surface and the often elongated, Gothic form and angular, spiky drawn lines of the Northern manner, to depict the deep drama of the women of all ages and stages of beauty, sexuality, despair and decay. Each is vulnerable, anxious, and mortal rather than only sexually available, and each is a character with an inner life, which to me takes the work away from misogyny.

Despite the disturbing violence depicted in these works, I find in many of Dix’s paintings of women something other than misogyny: the humanity of the women is never sugar coated into pneumatic attractiveness in the vein of John Currin, who Dunham mentions in regard to Dix’s sources in Northern Renaissance Germanic and Netherlandish portraiture. To the contrary, Dix adopts the detailed, delicate surface and the often elongated, Gothic form and angular, spiky drawn lines of the Northern manner, to depict the deep drama of the women of all ages and stages of beauty, sexuality, despair and decay. Each is vulnerable, anxious, and mortal rather than only sexually available, and each is a character with an inner life, which to me takes the work away from misogyny.