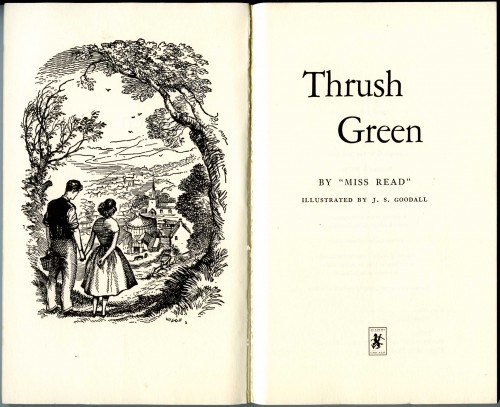

One of the strangest yet most memorable evenings of my life is associated in my mind with a book by an author who wrote as “Miss Read.” The book, Thrush Green, depicts a day in the life of a small English village, in fact, May Day, a day of festival. I had bought it because I loved all things English and was an Agatha Christie Miss Marple fan, still am. But as I began to read it, I felt that there was something weird about the book, it seemed somehow uncanny, it was not overtly or exactly a children’s book yet it was too simple to be a grown-up’s book, though, as I recall, there was a slight cast of dark doings in the village, not unlike the sinister activities in Miss Marple’s fictional village of St. Mary Mead where between tea parties with the Vicar people are murdered at an alarming rate without compunction.

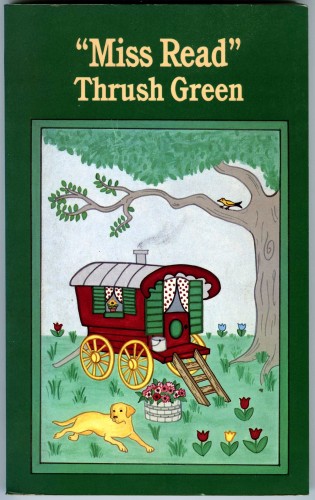

The author’s pseudonymic name, “Miss Read”–in quotes–added to the peculiarity. Another strange thing was that on the cover, that name was typeset as if it were the title of the book rather than the name of the author–top line, larger type. I felt unsure as to the book’s identity, its place in literature, its authenticity. What exactly was I reading, or, miss-reading?

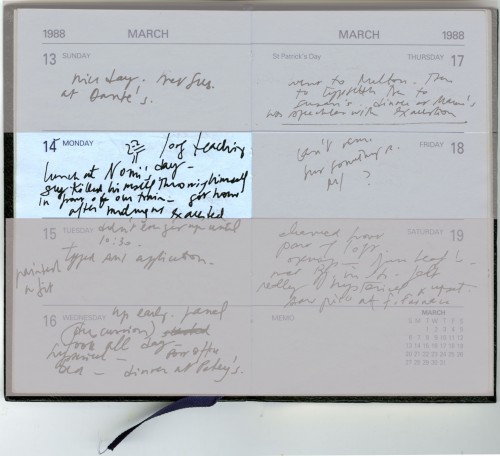

That night, March 14, 1988, I was on a train back from Providence. This was the semester when I taught a weekly graduate sculpture seminar at RISD, which felt pretty weird in itself: in those days disciplinary identities held more sway than they do now in art academia and, as a painter, I felt just ever so slightly inauthentic teaching “sculpture” students even though I had spent a year during that decade making three dimensional person-size figural sculptures out of chicken wire, plaster, and rice paper, tackling basic sculptural issues such as gravity and stability in a back-assed manner since I lacked any specific skills or training for the purpose and doing this with the purpose of bursting through the material and dimensional properties of my small works of pigment on rice paper to the more sculptural material of oil paint on linen, which was my goal.

Mira Schor, Birthday, 1983. Plaster and rice paper.

Once a week in the spring semester of 1988, I would leave the house at 7AM for the 8AM train to Providence, and all day I lived to get back on the 6PM train to New York. That night I was nearly alone in one of the old cars on Amtrak’s Northeast regional train line reading this strange book as the train moved through the dark night, when the train stopped suddenly in the middle of nowhere, about forty-five minutes south of Providence. We sat and sat and sat. Finally, after about an hour of mystery, incommunicado (pre-cell phone era), the conductor explained to the four or five of us in my car that a man had killed himself by throwing himself in front of the train and we were waiting for the local coroner to arrive so that the body could be removed and the train could move on. We waited another hour in what seemed both such a large space, an empty Amtrak train car, immensely solid and powerful–it had just killed a man–yet also a space completely insulated from the world, softly lit in the middle of darkness, before finally getting back under way. It was a unique and strangely beautiful night because of our solitude and safety just the length of a few train cars from the grisly horror, which we did not see, which had interrupted our path home, which had caused us to spend an indefinite amount of time in a still and quiet place of suspended animation, and which would never be spoken of again.

And I read Thrush Green. I thought the book was as fictional as was the moment in the sense that I did not quite believe that it was what it purported to be, a simple book about life in a rural British village. The night, the book, and its author remained a mystery on a train. But here in today’s Times is the obituary of the woman who wrote as “Miss Read,” a wonderfully apt name for an author, though her real name is as wonderful a name for a writer or a fictional character in a story set in an English village, Dora Saint.