I begin with a picture of me, but one where I am only an incidental subject.

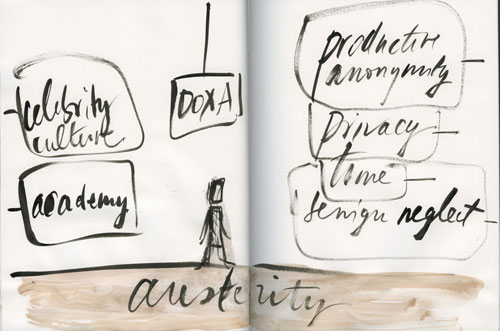

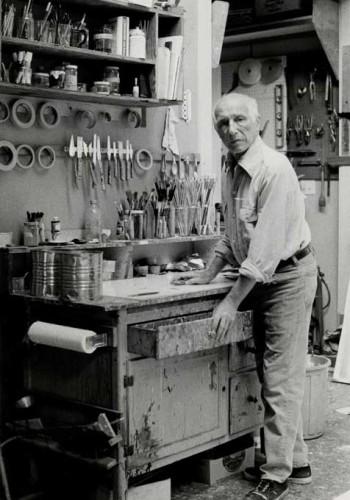

I am sitting in the studio of Chaim Gross at the Renee and Chaim Gross Foundation in Greenwich Village during an event on Chaim’s birthday March 17 (b.1902-1991). Because of a lifelong friendship with the Gross family, I feel I am at home in a space where I will not be judged, so I am comfortable sitting alone without feeling any necessity to fill the social space with small talk with strangers. I can take a few minutes of contemplation in Chaim’s studio. This space, even cleaned up and staged for its function in a museum, is a different kind of studio than the ones I often visit in my professional capacity as a teacher, where such tools are not available to the artist, both for practical reasons and also, sometimes, for ideological ones. I am surrounded by Chaim’s artworks, some of his art collection, and by his wonderful tools. I am surrounded by color and materiality and the purpose of craft.This is officially a historical space, a museum; it is an encapsulation or a representation of a practice which is not only historic but historicized. Someone has caught me unawares, as I consider how I am being historicized through my own craft practice, as “someone who uses art supplies to make art,” as a friend has recently described my rare and dying breed, through my knowledge of these spaces and the practices that took place within them, through such associations that I cannot erase, that is, historicized through that inevitable but shocking process wherein the valuable knowledge one acquires over a life time is suddenly held by some as irrelevant to the problems of the present and the future.

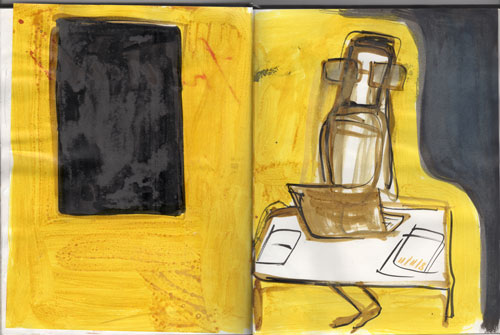

A few moments after this picture was taken, I turned my head slightly and focused on a chair.

It is just a chair, an earlier era’s successful design for a work chair of adjustable height. It is also delicately ornate, with an art nouveau line. And it is old, so the wood and metal framework have a patina that maybe were not part of its original condition, but the curving lines, the darkened metal, and the worn and stained wood concentrate my attention: here is something that offers an alternative to the current design of chairs favored by institutions.

Theoretical discourse does not elect to keep practices at a distance, so that first it has to leave its own place to analyze them and then by simply inverting them may find itself at home. The partitioning (découpage) that it carries out, it also repeats. This partitioning is imposed on it by history. Procedures without discourse are collected and located in an area organized by the past and giving them the role, a determining one for theory, of being constituted as wild “reserves” for enlightened knowledge. (Michel de Certeau, p64 The Practice of Everyday Life)

Some of Chaim’s tools are on view,

The studio is in an order and a degree of cleanliness that is a function of its being a museum, not a place of current work. But Chaim was a professional man and a craftsman so I am sure that his tools were kept in good order in this system he worked out for himself.

Chaim was one of the three men in my childhood who I was able to observe at work or at least was able to observe the working studios of.

The painter Jack Tworkov was another. He too cared deeply about quality of craftsmanship, whether it was how to construct the surface of a painting or restore the surface of an old oak table or bone and stuff a leg of lamb, and his tools were remarkably well organized and maintained.

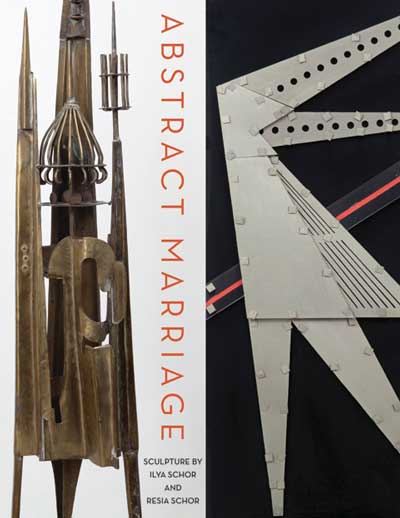

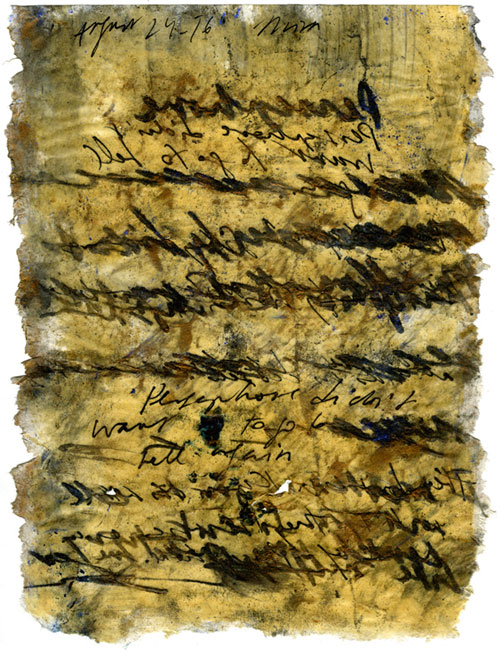

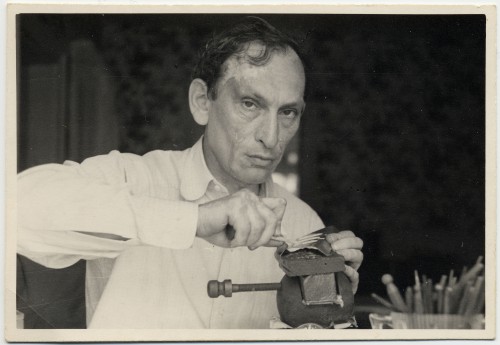

The first and most important artist I was able to observe at work was my father Ilya Schor. Today is his birthday: he was born in Zloczow, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, April 16, 1904.

As a teenager he was apprenticed to an engraver and goldsmith before he went to art school. This seems to have been the remainder of a European craft guild system and the tools were probably closer to those of the 15th century than to today’s. For example, soldering was done by propelling the flame through a tube using with one’s own breath. My father used to smoke 4 packs a day in those years, but, a young man, he could do that.

Ilya Schor c.1920 (at the left)

In 1937 he brought this drill from Poland to Paris, where he still used it, and from Paris to Marseilles, and from Marseilles to Lisbon, and from Lisbon to New York. This drill survived the Holocaust. Of course he did not use it anymore when I watched him work, he had an electric drill. But he showed me how the old one worked. It was clear that it was archaic, even for him, but it created a living bridge bringing me as close to when men made fire by striking two flints together as to the technologies of my own time.

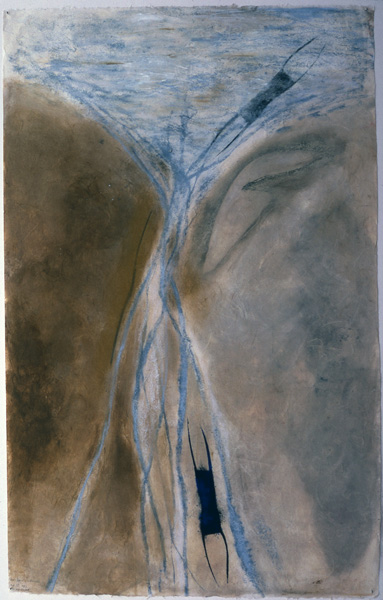

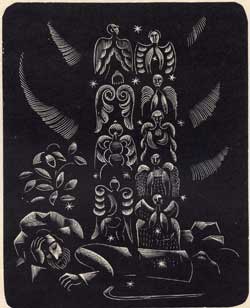

Watching him engrave on hardwood was a great show: his movements were careful, accurate, but also swift and deft. I loved watching him roll out the thick black printer’s ink on a piece of glass, and I loved the rounded wood tool that rubbed the paper against the block to catch the ink smoothly, and finally I loved the revelation of the reverse image when the paper was pulled from the block.

To hold small silver objects secure while he engraved them, he embedded them into tar, which he softened with the flame of a Bunsen burner. The tar formed the top surface of a T-shaped block of wood which fit into the slot of a heavy base which he could swivel with his left hand while engraving with his right. The two part base is made of solid metal, the spherical section is like the turning orb of the earth, and with a similar density, I’m pretty sure it is made of lead.

This was all a long time ago. Around the world, artisans today may still use similar tools but technological transformations in the production of sculpture, images, and objects of all kinds are always privileged signs of contemporaneity. If they were starting out their art lives today, these three artists, born within four years of each other, all from the area of the pale of settlement, Chaim, Jack, and Ilya, would most likely be at the forefront of technological innovation, bringing as much ability and ingenuity to new methods of production as they exhibited with the tools they were given. People sometimes ask me if I am tempted to take up my father’s tools, the way my mother did after my father died, but the craft is in fact very hard, physically arduous, and without much beyond the most basic training even harder, and if I sometimes consider having some of my mother’s jewelry produced as multiples (another story for another day), I think more in terms of 3D printing in plastic! But if they would have opted for the new, if I too would opt for the new, nevertheless there was a tremendous satisfaction for them in their ability to manipulate materials, of a job well done in the working day, and there was tremendous pleasure for me in watching them work. I still love watching things being made. And most importantly, it was evident even to me as a child that there was an intelligence in the craft, in the gesture.

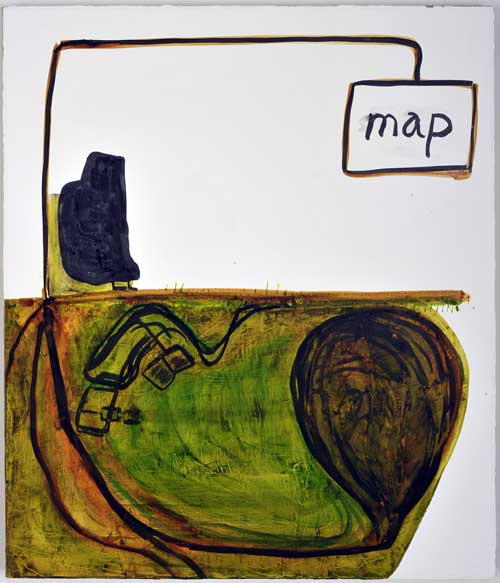

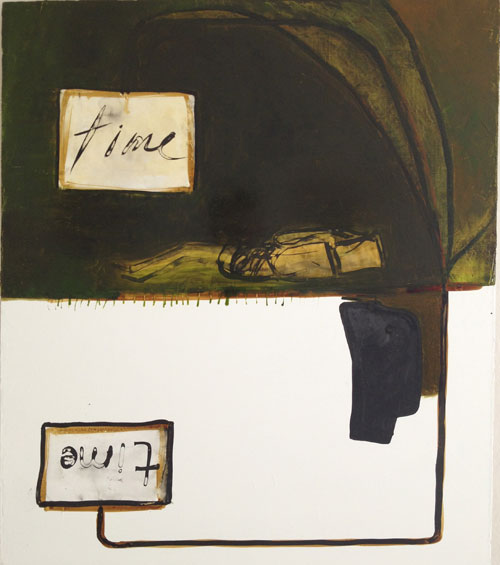

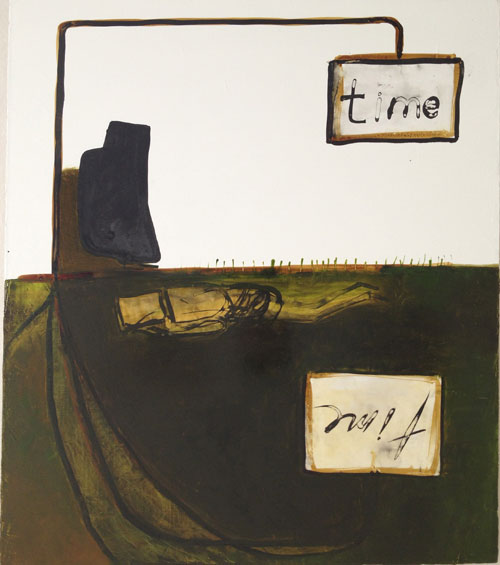

Returning to the chair in Chaim’s studio, it became a figure in a painting, in which furniture of the “hot desk” studio of the present/future and of the old painting studio of the past exist in a perpetually reversible relation of metaphoric temperature.