In Jerry Saltz’s recent New York Magazine piece, “Generation Blank,” he expresses some concern about young contemporary artists making “work stuck in a cul-de-sac of aesthetic regress, where everyone is deconstructing the same elements.”

I don’t disagree with Saltz’s assessment. In fact I examine in great detail the phenomenon he notes in this article in “Trites Tropes,” which is the last section of my book A Decade of Negative Thinking: Essays on Art, Politics and Daily Life (Duke University Press, pub. date 2009, appeared winter 2010).

I hope people will read my book–of course!–so I won’t (& can’t) quote the entire section of the book relevant to this subject, which included an analysis of contemporary trends in art education, and a long examination of journalistic coverage of recent MFA generations’ entry into the art market, but I will refer to it here and I’ve inserted some relevant quotes at the end of this post.

Saltz writes that a “feedback loop has formed; art is turned into a fixed shell game, moving the same pieces around a limited board.” Again, I agree. In fact amusingly enough I can make the small claim to my place in a chronologically earlier spot on the chain in the “feedback loop” of criticality of the system: in my introduction to A Decade, I wrote that, “I want to address artists who are encouraged on many fronts to operate in a limited field of new cookies by exploring instead the potential of a critical but productive temporal counterpoint, a constant movement between the undertow of the past beneath the wave of the present, and the powerful counterflow of the present over reiterations of the past in contemporary art works and ideologies. Contested histories, networks of influence, and feedback loops of recurrent tropes emerge as major themes.” (emphasis added for this post). Well, neither of us invented the term nor its overuse!

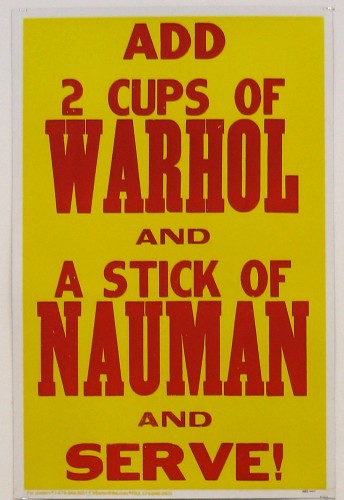

Carl Pope, from the "About Bad Art"poster series, 2008, Letterpress broadside, 17"x26"

Throughout the book and in some recent blog posts, I note the apolitical tendencies of many members of these recent generations of artists: even when as individuals they have progressive politics, they are undermined by a certain passive despondency and their tentative critiques of socio/artistic situations and conditions they sense are problematic are unsupported by any radical movement in our society as a whole.

A general atmosphere of a new conservatism among twenty and thirty somethings is evident on all societal registers: just yesterday an article in the New York Times, “How Divorce Lost Its Groove,” examined attitudes towards divorce among a younger generation of upscale people with small children. Without wishing for a moment to diminish the anguish that this generation, many products of divorce themselves, may have experienced, it was disturbing that the article did not look at other contemporary trends (overall drop in marriage rates, more children born out of wedlock, more unusual family arrangements) nor did it raise any kind of feminist analysis of the return of normative pressures on young women to marry and have children in a Leave it to Beaver sort of way, albeit in the igeneration mode where mothers work outside the home.

The conservatism emanating from the opprobrium and shame experienced by these affluent young divorcees is also apparent in the MFA generation of artists who have learned all the rules of the art market, are incredibly professional and well-behaved, and would never dream of questioning the status quo of the art market beyond a certain point of academic correctness. And why would they when most of the contemporary critics who these artists follow inevitably preempt any tentative attempts at critique of the obscenities of market by prescriptively concluding that it is naive to imagine one could avoid it. Resistance, one is told every which way, is not just futile, it’s unrealistic, stupid even. Or, as one of my friends said to me once, in the early 80s, when I started not being with the new program, “Oh Mira, you’re such a hippie!.”

While my friendship with some young artists with an impressive commitment to social justice troubles my ability to make blanket statements, I have a lurking fear that a terrible generational reversal has taken place that almost goes against the laws of nature: my generation used to say, “don’t trust anyone over thirty,” and when I consider that my fate as an older person is to live in the world that will be led by the privileged few among the current generation Saltz is calling “Generation Blank,” I would have to say that I don’t trust anyone under thirty! under 40, even under 50! the farther you get from the generative decade of the 60s and yes the 70s, the worse it gets–that is to say the overall 25 to 40 demographic group with its corporate smoothness of operation and its Darwinian positivism, not the wonderful individuals scattered within that demographic who have the desire but lack the will towards a critical mass necessary for a movement of social change.

Or, let me put it this way, the faculty evaluation I take away from this past year is one anonymous student writing, “and she made us watch a speech by Martin Luther King Jr.” This, about one of my graduate seminar classes in which, with the encouragement of one of my more radically minded students mind you, I had them watch King’s “Beyond Vietnam” speech, which he delivered at New York’s Riverside Church on April 4, 1967, a year exactly before his assassination, was a bad thing, from her (I’m guessing) point of view.

Perhaps this student was right to complain because listening to a great anti-war speech by Martin Luther King Jr. was indeed a waste of time in that it would do nothing to enhance her competitiveness in the current gallery scene in New York City or the art world in general, but on the other hand you could argue that only by taking such unorthodox breaks from the usual suspects of art academia’s prescribed reading lists and listening to speeches like that is there any hope of developing an art practice that would go beyond the predictable politesse of Recipe Art.

In this case Saltz should at least qualify his recommendation that young artists stop looking in awe at their elders: it all depends on which elders, the ones who created something interesting and then got complacent in the international art market or those who have retained some kind of radicality, whether political, or a radicality of individual critical thought and personal necessity within a rigorous formal practice. It also depends on whether the radicality of the gesture is foregrounded, its context and meaning before it was chosen to be consecrated by art history and the market, or whether the orthodoxy of the image, that is to say the appearance of radicality, once it has been sufficiently absorbed by the system and given the sheen of celebrity, is the focus of instruction.

Saltz doesn’t seem to question his own underlying assumption that interesting new work would come only from the young or that it would be easily visible or foregrounded in mainstream exhibitions and media. This is a reflexive point of view shared by many in art journalism and academia, where only the new and the young are conceived to be contemporary or marketable, even though given the generational political conditions many including now Saltz have noted and that I describe in my book, it is possible that this new and young generation has been shaped for conformism to a corporate ideal, albeit a newly global one, in such a way that they are the last place to look for interesting art that would break any molds.

My response to my unidentified student’s evaluation was to devote a couple of classes the next semester to the applicability of the concept of non-violence to art (see my earlier post, “While Working on a Syllabus on a Winter’s Afternoon”). I assigned a number of atypical (for a standard first year MFA Graduate Seminar) texts such as War and the Iliad, with Simone Weil‘s essay “The Iliad or The Poem of Force” and Rachel Bespaloff’s contemporaneous but lesser known essay, “On the Iliad,” and Mark Kurlansky’s Non-Violence: The History of A Dangerous Idea, because I wanted to bring attention to the model of patricidal Oedipal rebellion as central to many avant-garde gestures. I wanted to look to principles of non-violence as a political strategy to think of ways of existing in without slavishly adhering to the values of a market-driven, spectacular, declarative art economy. [Glad I got that particular class in, because it was very meaningful, I think, in its content and its diversion from the usual course of study in an MFA program, and because the course, which otherwise included the usual suspects of art writings intended to bring students coming from a variety of educational backgrounds up to speed, was displaced from the curriculum at the end of the semester in favor of something new.]

But, to trouble my own point, because recognition of contradictory forces and truths is one of the ways forward, there are many works by young artists that do indeed “[enlarge] our view of being human,” (Saltz), though perhaps in ways that we find disconcerting, for the political reasons touched on above. I’ve always looked with great interest to work that is antithetical to what I had thought was my viewpoint, because it is all political utterance, no matter what I, at first and perhaps finally at last, think of it, and I learn from it.

Here are some excerpts from A Decade of Negative Thinking:

from the “Introduction”

A few years ago, during a break from teaching, I was enjoying my favorite snack: a Madeleine dipped in espresso. One of my students asked me what I was eating. A Madeleine, I said. I explained that it was an important part of the history of literature, that, in Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, the act of dipping a Madeleine into Lime tree tea, or “tilleul,” released the totality of the author’s memories of his childhood and the meaning of the work he was undertaking. “Oh,” my student said as he walked away, “I learned something new today.” “About Proust?” I said hopefully, ever the pedagogue. “About a new cookie,” he said.

This book is not exactly about new cookies.

It is perhaps a liability to advertise that to my prospective readers! People are interested in books that will give them a heads up on the next cookie – I look for such volumes myself. But, in fact, most books are about the past: only the journalistic publishing cycle and Internet manifestations occur in the present, everything else is by necessity retrospective or predictive. In a culture focused on the celebrity of the new, there may be some material of interest nestled elsewhere.

The first several pages of Du Côté de Chez Swann are devoted to an extended, detailed to the point of being soporific, description of the mechanics of falling asleep. I considered reading it out loud to my class that year but thought that the slow pace would seem like abuse to them. Yet we all need sleep, we yearn for deep and restful sleep; desperate, we skip the stages of experience described by Proust and just reach for the Ambien.

In this space bracketed by artificial stimulation and sedation, I want to address artists who are encouraged on many fronts to operate in a limited field of new cookies by exploring instead the potential of a critical but productive temporal counterpoint, a constant movement between the undertow of the past beneath the wave of the present, and the powerful counterflow of the present over reiterations of the past in contemporary art works and ideologies. Contested histories, networks of influence, and feedback loops of recurrent tropes emerge as major themes.

….

…[T]he section of the book titled “Trite Tropes” … groups four distinct yet interrelated essays. The second, third, and fourth follow from the first, but each has a different focus, tone, and timeframe. “Trite Tropes, Clichés, or the Persistence of Styles” calls attention to the continued currency, in American art and art education of a multitude of obsolete styles, often transmitted to and practiced by art students with an eroded consciousness of these styles’ original histories. In “Recipe Art” I examine the flip side of this phenomenon: the success in recent years of a style that is constituted by the ability to successfully configure a set of diverse but predictable tropes in terms of subject and types of appropriated material–one from column A, one from column B–into an art work that can be quickly described. In “Work and Play” I look at political video cartoons from the 2004 election cycle, and in “New Tales of Scheherazade” I examine recent art videos with political content, all works which offered me as a viewer an escape from the predictability of much recipe art.

…

From “Recipe Art”

While the persistence of styles may be fostered by those art teachers who teach what they learned in a two year window of time of their own schooling, gradually transforming art philosophies into sets of visual habits while overwhelmed by the increasingly corporate academic frame, recipe art emerges from the complicity of some fine art departments and schools with the values of the art world and art market. In fact such complicity is a prerequisite of success for the institution, whatever its actual impact on art. … A couple of years ago, one of the institutions I teach at sent out a card announcing a panel on “self-promotion for artist and designers,” “The Brand Called You” and a 2008 course offering, “Internet Famous,” is described as “the first class in the history of academics where software awards each student a grade based on a quantitative measurement of their web fame,” or whether they are “famo.” Many MFA programs have professional practices courses, in which students hone their skills at, for instance, “the elevator pitch,” where they have to condense a spiel on their work that will last no longer than an average elevator ride with a prospective collector or dealer. These are certainly practical and realistic studies in the current cultural economy. But one of the effects of this pressure is to encourage the formation of work that can be boiled down to a few words: recipe art. Then the art world grabs the graduate school product the most likely to rely entirely on clever recycling of currently appropriate obsolescent styles. The predictability of the work produced in this system creates an undercurrent of nihilistic cynicism that is expressed in the often extremely nasty dismissive tone of the comments on websites that discuss recent art work.

…

[m]arket pressures disable artists from moving through stages of influence at the pace each individual might need. Only the most facile, the quickest studies succeed in the short run, freezing into formulaic product what might in the past have been just a stage towards more individualized work. Market success makes one stubbornly resistant to change. And who am I to argue with success? Or, put differently, the young artist can think to himself, who is she to argue with my success? The artist who has learned to deploy the most current tropes is likely to be showing their work and even selling it, and it is hard to critique artists at such (usually fleeting) moments in their career.

….

In fact you don’t have to force capitalism down the throats of young artists who have been bred into an unquestioning acceptance of its rules and recipes, even if they will in most cases ultimately be among its many victims. There have always been business savvy artists and there have always been very rich, socially ambitious collectors. The media has always participated. The difference is one of scale of money, amount of artists, and of lowering of the age of entry. Most importantly, this generation of art students was formed during the Reagan Bush era when anything resembling true critiques of authority and power have been methodically ridiculed, demonized, or erased, creating a cohort that is surprisingly obedient and conformist, when not imbued with a sense of hopelessness.

…

[M]ost contemporary critics who even attempt a critique of the obscenities of market conclude that it is naïve to imagine one could avoid it. So in the guise of a rather fatalistic realism, we are always returned to the market’s axiomatic presence, its existence as essence. The nature of what might be an alternative system is not given the time or space by mainstream art media — “Artforum/Karybdis,” the whirlpool who regularly swallows up all those who cross its turbulent waters operates according to the dictates of a commercial calendar that does not allow attention to ideas and art works that are not immediately part of a specific market economy. In fact, when something does appear in print without a commercial hook-up, you look for one anyway because there is no way that it can be there just because it is interesting.

If it has always been so, nevertheless, read against the backdrop of incipient global war, over resources and religion, with a tremendous toll on not only the poor of the world, but also the educated middle classes and women, the triviality of much of this artistic and commercial discourse has been hard to countenance.

….

Recently, in an effort to reinforce the link between seminar readings and studio practice, after my students read various standard texts on appropriation and simulation, including Hal Foster’s “The Expressive Fallacy,” I asked them to make two art works on the same subject, the first using appropriational techniques and strategies, the second working expressively. The results were disappointing. At first I felt that their use of appropriation was timid and inept, which seemed strange considering the pervasiveness of appropriation in the culture at large. Next it occurred to me that the real difficulty might lie in doing something expressively, with any authenticity or necessity at the level of the image, the story, the stroke, the line, the object. It is a strangely complex paradox: self-expression and authenticity form the bedrock of the rhetoric of art practice, yet the critique of authenticity and originality have been so effective (even when the artist is uneducated to theory), and also simulation, conventionalized commodification, and sampling are so present in every day existence, that the hardest challenge for an artist today is to make an authentic mark that represents personal or formal investigation. My students’ predicament suggests that current cultural conditions are such that Recipe Art may be the only solution for a majority of artists who are trapped between a surplus of cultural quotation and the present loss of access to anything passing for an “authentic” artistic gesture.

[…] come Saturday it will looks as if a tornado has picked up a Prada store and dropped it on a desolate strip of U.S. 90 in West Texas. That is where Prada Marfa, a permanent sculpture by the Berlin artists Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset will be installed. […] The sculpture is meant to look like a Prada store, with minimalist white stucco walls and a window display housing real Prada shoes and handbags from the fall collection, But there is no working door.

So, I walk into a studio and I see something I’ve seen a million times before, at best the successfully articulated latest model of the latest style. I walk into a gallery, and I see – the same thing I just saw in the studio, a mis-en-abyme of cultural reference, yet another endless loop of appropriation. The work was made to be incorporated into the market and the discursive stream of the academy. That its originality is homogenized is part of its ethos. It may be chillingly, even heartlessly proficient, but that proficiency is a good indicator that we find ourselves in the Neo New Academy.

….

from “Work & Play”

For the inaugural exhibition of its satellite location in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, the artist Emily Katrenik is eating the wall that separates the gallery’s exhibition space from the bedroom of its director […] Video of her ingestion is included in the exhibition; she also removes some of the plaster and bakes it into loaves of bread, which are available for gallery visitors to sample.

What really matters, I mean, really, beyond the rhetoric of it mattering, is having something to say that can truly reinvest familiar materials and forms with cultural energy. What makes something at least temporarily uncategorizable in relation to history and to ambient cultural language may require a self- and other-criticality that in some artists takes decades, not months. Yet now there is no time for the slow aesthetic growth that used to be one of the standard myths of origin. Meanwhile every stroke, blob, or pixel has been analyzed, recycled, branded, as every trope has been trumped.

The question is where to look for the work that really alters your world, not just the work that tells you why this world is so mutantly oriented to the commodification of tropes. Or, having had my methamphetamine, my hit of the latest re-articulation of the near-past and the “next-modern,” I need something I would describe as real food. I walk into a museum and have an intimate relationship with a random artwork or artifact from the past that suddenly speaks to me – if I am in a museum that still allows for private experience. Or I take advantage of the exit conveniently gnawed open by the artist ingesting or regurgitating the possibly toxic confines of the spaces of art, step outside, and turn to other modes of expression and cultural action than high art.

For more of this material I hope you will look at my book. You can also check out the following:

“The Art of Nonconformist Criticality.” This talk, on Feb. 14, 2006, was the second in a series launched by the newly formed MFA Art Criticism and Writing Department at the School of Visual Arts (90 minutes, also available as video on SVA’s itunes University site, under Lectures in Art Criticism).

And forthcoming: a new essay, “Fail!,” in a forthcoming issue of Paper Monument.