For the past ten years on September 11, I’ve republished a text I wrote in the weeks after that day, to bring the texture of the event as witnessed by so many New Yorkers with their own eyes and of daily life in Lower Manhattan in the days and weeks afterwards. But this year I don’t feel like it. My need to continue the memory has been interrupted by the National September 11 Memorial which I visited November 15, 2011, for which friends and I had reserved tickets two months in advance and which turned out to be on the same day that a police raid had evicted Occupy Wall Street from Zuccotti Park.

That day I wrote down my impressions, perhaps today’s eleventh anniversary is the day to publish them.

My initial notes as written in bold face on the spot went as follows: 9/11, 45 min wait, airport security, bad vibes, hideous entrance, bad plaza (Starbucks, Metropark architecture & lamps), terrible compromise but the two pools are dark, black abyss, death, a cold corporate architecture really works, it looks both small and huge, like a simulacral sea, it’s the opposite of the Towers of Light, what goes up via light into dark here cascades down into dark.

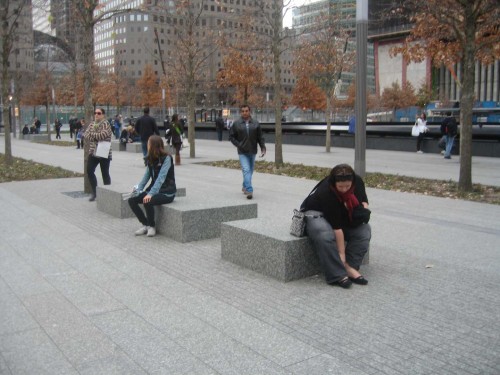

Getting to the entrance of the memorial is an ordeal, today (November 15, 2011) an ordeal twice over. First the issue was how walk past Zuccotti Park without having time to stop to photograph the police occupying the Park. Then, corner Thames and Albany Streets, the interminable and graceless line to get into the Memorial.

This is not a promising beginning to the memorial experience. You shouldn’t have to make an appointment to visit a memorial. Even if admission is free, grief must be free to roam and it must be integrated into daily life, here the grid of Lower Manhattan, to be both special and a silent partner, there if you want it, when you want it. Last fall, a two-month wait for a daylight hour visitor’s pass was followed by a 45 minute wait in a line effectively several blocks long though snaked through police barricades on the South side of the WTC construction site (to the accompaniment of construction noise that would certainly drown out any noise from OWS). We went through three checkpoints with our visitor’s pass, only to find ourselves at the end of the line in a chaotic mini-airport security situation, with metal detectors, put your coat and bag in a plastic bin (you don’t have to take off your shoes, thank goodness given how chaotic the situation was, I figured the logic of that was that if you blew yourself up you wouldn’t take anyone else with you though the logistics were such that people would be trampled in the line slowed down). Then down another bleak work barricaded back area, and finally into the Memorial Park…you hardly know once you have entered because there is no entrance as such. So far, bad vibes and not because of memories of why you have come, in fact the wait is so unpleasant that by the time you’ve been on line for an hour or so, you forget the reason you came.

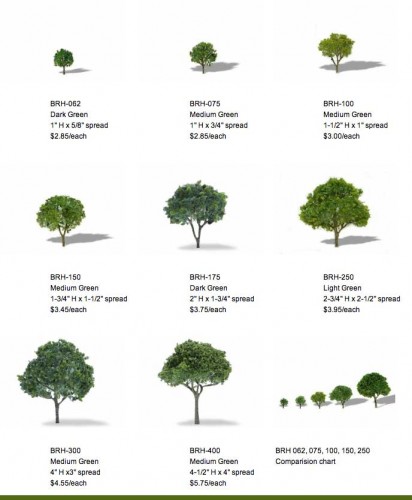

The plaza won’t help you remember. It’s really spectacularly mediocre, New Jersey Transit/ Metropark train station parking lot atmosphere including the lamps, at the moment rather silly looking trees that somehow never transcend the function of little architectural model fake trees.

The plaza has no sense of scale. Perhaps if and when the area is no longer a work site and if in that case there is free access from the streets around, there will be a flow into the life of the city, that might make it better, but as my friends pointed out, the plaza at the World Trade Center was always a cold windswept bad space. Still, we imagined various alternatives: the last vestige of facade, the bronze orb, damaged yet intact, or just the gravel of a Japanese rock garden would be better. Best would be a flat plain space with no adornment, just gravel or marble, the trees are silly, a false niceness.

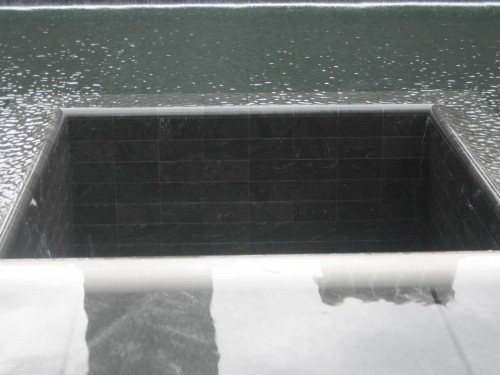

The pools are the thing itself, death, loss, the abyss, the unknown.

You approach the first pool set into the footprint of the North Tower. It is both small and huge, it seems as large as an inland sea, though a strangely simulacral one, like in a sci-fi movie, yet too small to have been the footprint of such a tall building, and though ocean-like, probably the water is only one foot deep.

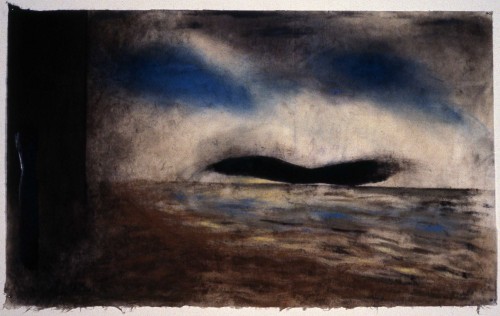

Inner Sea, a work on paper I did in 1981, from a dream of a vast sea within the interior of an urban structure

A shower of water cascades down the four dark stone walls of the giant square into the darker seemingly bottomless abyss of the inner square at the bottom of the pool.The water passes through a kind of comb that subtly recalls the e style arches of the WTC facade, though here the pattern goes downwards.

The design of the pools is brutal, corporate, and it really works.

Morning of September 11, 2012

As the reading of the names proceeds in the background, a kind of musical chairs game of loss–on whose name will the reader stop to reveal their particular relation of grief?– I get out James E. Young’s At Memory’s Edge: After Images of the Holocaust in Contemporary Art and Architecture, and look again as some of the examples of “counter-memorials” in Germany in the 1990s, including from among the submissions to a 1995 competition for a German National “memorial to murdered Jews of Europe.,” in the chapter “Memory, Countermemory, and the End of the Monument: Horst Hoheisel, Micha Ullman Rachel Whiteread, and Renata Stih and Frieder Schnock.”

Artist Horst Hoheisel … proposed a simple, if provocative antisolution to the memorial competition: blow up the Brandenburg Tor, grind its stone into dust, sprinkle the remains over its former site, and cover the entire memorial area with granite plates. How better to remember a destroyed people than by a destroyed monument?…Hoheisel’s proposed destruction of the Brandenburg Gate participates int eh competition for a national Holocaust memorial, even as its radicalism precludes the possibility of its execution. At least part of its polemic, therefore, is directed against actually building any winning design, against ever finishing the monument at all. Here he seems to suggest that the surest engagement with Holocaust memory in Germany may actually life in its perpetual irresolution, that only an unfinished memorial process can guarantee the life of memory.

Some more general remarks by Young have bearing on the type of memorial that has become the default style in the United States, first expressed in Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial which so brilliantly melded modernist abstraction with literary content-the names etched on the marble surface. Lin’s piece has a quality of the antimemorial, as it is set into the earth and is quite un-obstrusive in the landscape, really it is an inscription into the earth (see picture on Wikipedia site as observed from above) until you are right up along it where only at its center does it reach above the visitor’s head. A visit to it is a surprise, because it just kind of appears as you walk towards it and its meaning can only be understood through walking by with your body and observing other people interacting with it. It’s intimate. What the designers of the 9/11 have borrowed from Lin is the most successful, thus architect Michael Arad‘s design for the pools and his use of inscribed names. The landscaping is clearly a huge concession to the demands of urban planners, politicians, victims’ families, and real estate forces who would not have understood a less utilitarian and conventional approach.

Like other cultural and aesthetic forms in Europe and North America, the monument–in both idea and practice–has undergone a radical transformation over the course of the twentieth century. As intersections between public art and political memory, the monument has necessarily reflected the aesthetic and political revolutions, as well as the wider crises of representation, following all of the century’s major upheavals–including both World Wars I and II, the Vietnam War, the rise and fall of communist regimes in the former Soviet Union and its Eastern Europeans satellites. In every case, the monument reflects both its sociohistorical and its aesthetic context: artists working in eras of cubism, expressionism, socialist realism, earthworks, minimalism, or conceptual art remain answerable to the needs of both art and official history. The result has been a metamorphosis of the monument from the heroic, self-aggrandizing figurative icons of the late nineteenth century celebrating national ideals and triumphs to the antiheroic, often ironic, and self-effacing conceptual installations that mark the national ambivalence and uncertainty of late twentieth-century postmodernism.

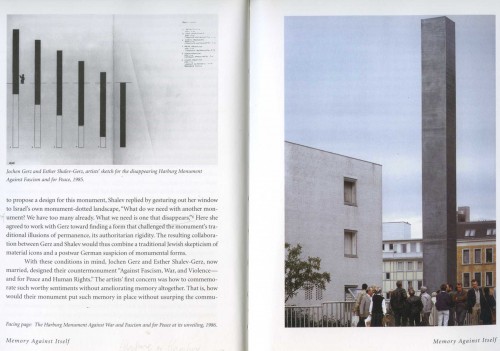

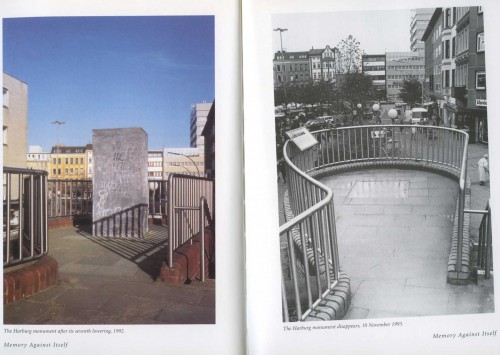

A number of the monuments described in the book seem to have a relevance to the 9/11 Memorial. Artist Jochen Gerz and Esther Shalev-Gerz‘s The Hamburg Monument Against War and Facism and for Peace, from 1986, was a “forty-foot high, three foot-square pillar ..made of hollow aluminum plated with a thin layer of soft dark lead. Visitors were invited to inscribe their own names on the monument with a steel pointed stylus and as soon as a five foot section was filled with names it sank “into a chamber as deep as the column was high.” Over seven years the monument disappeared. “The best monument, in the Gerzes’ view, may be no monument at all, but only the memory of an absent monument.”

An unrealized project submitted to the 1995 competition by Renata Stih and Frieder Schnock also stays in my mind: Bus Stop–The Non Monument proposed “an open-air bus terminal for coaches departing to and returning from regularly scheduled visits to several dozen concentration camps and other sites of destruction throughout Europe.” The artists called for “a single place whence visitors can board a bright red bus at a regularly scheduled time for a nonstop trip both to such well-known sites as Auschwitz, Treblinka, and Dachau and to the lesser known massacre sites in the east, such as Vitebsk and Trawniki.” Finally, “at night the rows of parked and waiting buses, with their destinations illuminated, would become a kind of “light sculpture” that dissolves at the break of day into a moving mass to reflect what Bernd Nicolai has called “the busy banality of horror.”

You know that the designers of the 9/11 Memorial were well versed in the history of these memorials and countermemorials.

November 15, 2011

Speaking of unwelcoming windswept spaces, on my way home I circled Zuccotti Park, now occupied by the NYPD, with Occupy Wall Street, ordinary New Yorkers, and the press occupying the periphery. In a weird topsy turvy opposites world, the police now occupied the park, and the occupiers surrounded them.

*

The problems of the 9/11 memorial and the political atmosphere that led to the Occupy movement are linked, as the reaction of the United States to the attacks of September 11 in some way was a disturbing mirror image of the forces that attacked on September 11 (a mirroring described in the 2004 BBC Documentary The Power of Nightmares, which posits parallels between the rise of the American Neo-Conservative movement and the radical Islamist movement, making comparisons on their origins and noting strong similarities between the two. In a way the destruction of the United States continued via its own internal processes of paranoia and ulterior political motives unrelated to the actual event–let’s just start its wasting of resources on a war on the “wrong” country…many others have developed these ideas better than I can do.

*

The truest antimemorials to 9/11 were perhaps the modest, temporary ones that sprang up on the site in the months after September 11, and the simple constructions on the site that were built for early anniversary observances.

Site of the World Trade Center, cardboard circle, September 11, 2002, New York City

And the most outstanding memorial remains The Towers of Light, or The Tribute in Lights. It seemed last year that we were seeing the last of them as authorities were grumbling about electricity costs. But tonight as in the past several years I’m going downtown to get as close to them as I can.

I don’t plan to go back to the Memorial until it is, if ever, integrated into the flow of the city, and I can walk there as my feet and spirit take me. That would be what–one little fragment of–democracy looks like.