The essence of love is that you never know from where Cupid’s arrow will fly.

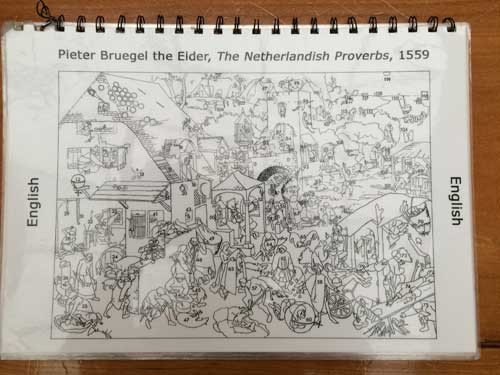

I went to Berlin for the first time last month, in part because I needed to find new old art to love, old great art that would be new to me. At the Gemaldegalerie I found many paintings to love, including several that I had loved in reproduction all my life, but the piercing arrows were cast by two paintings I either had never been aware of or had not fixed upon before: Lucas Cranach The Elder‘s The Fountain of Youth from 1546 and Pieter Bruegel the Elder‘s Netherlandish Proverbs from 1559. It is these two paintings that I want to spend some time with here, on the fifth anniversary of A Year of Positive Thinking.

My comments are based on my own observations and thoughts rather than upon research because no amount of historical background or exegesis can help in understanding the paintings at the level of their presence, as I was able to apprehend them in the moment with whatever knowledge of anything which I brought to my encounter with them. My writing can only mimic the fragmentary efforts of an ant crawling over a large area whose totality can only be understood in a partial manner, in fact those of an ant crawling over a formicarium teeming with ants, because each painting is filled with many small human figures and foils any viewer’s desire to take something in totally in one glance, our patience for detail bracketed as it is by the totalizing aesthetics of modernism and the shattered attention span of an Internet addict.

I came upon Cranach’s The Fountain of Youth as one might come upon such a fountain, in a strange grove, “per una selva oscura.” It is a difficult painting to take in though it draws one to it. A large painting populated by many small figures, the museum has placed it between two monumental Cranach paintings of Venus and Cupid: in one, Cupid, caught stealing honey, is attacked by bees which seems to hamper his vision of the beautiful figure of Venus towering above him. These two large and bewitching nude figures are the honey pot that lure us in to the core of the installation, the curious horizontal painting for which they are the caryatids. As one draws closer, as close as the museum allows, which is never close enough for me, how strange is the representation, the degree of realism versus the traces of the Gothic: this is not a painterly painting and the figures are at first like charming figurines, then one begins to notice the verissimilitude, the proportional and extremely detailed representation of the aged body, sagging breasts, thinning hair, toothlessness, lines, exhaustion….like an ant I am crawling over the details, I don’t yet see the forest or the clearing for the trees. I don’t yet even see the trees fully, that is, the individual figures. That takes more time.

Individual figures and vignettes begin to draw you in:

You dive into the fountain of youth.

Gradually you realize the painting is a narrative, represented by a horizontal progression from left to right. No, that’s not correct. I should say I gradually realize, because I have approached this painting in a kind of a daze, it has cast an immediate spell. Even reading the title hasn’t created the bridge between what I am seeing bit by bit and what the title says it is about. I must read the painting, not the title.

People arrive to a clearing in a rocky landscape far above and beyond the walls of a city. They come by cart and horse through a passage of boulders. They are carried on people’s backs and pushed in wheelbarrows. In the center of the painting is a pool filled with water springing from the fountain, a tall column topped by a small statue of Venus and Cupid. In the pool are women, only women: on the left of the pool they are old, the water and the figures are tinged with grey, on the right the water is mauve, the bodies pink and pneumatic (by 16th century standards). The women are young and frolic in the water, one swims, others wash their now flowing golden locks. Whereas on the left, the women have or are allowed no shame, as their aged failing naked flesh is examined by doctors, on the right while some girls preen without care and one poses and looks directly at us the viewer, another covers her pudenda in a classic gesture. At the right edge of the pool they are greeted by gentlemen and led to a red tent from which they emerge stage right beautifully dressed. The story ends in vignettes of celebration: a couple has a tryst behind a bush at the bottom right of the painting, and the narrative ends in a picnic and dance that takes place in the background right, above the main diegetic strip.

This is a philosophical journey through life in reverse, it is a dream: as in a sci-fi movie, the newly young do not look back, they do not remember the drama of their old age, just as in life when the movie is run in the right chronological direction, youth cannot really see old age as anything that will affect it, it believes itself to be immune to that depredation of time.

The painting is unified by a strip of earth that runs across the bottom of the painting, this area of the painting is perhaps darkened by time, its rich green and brown darkness with beautifully painted blades of grass, sets off the light of the principal scene, like the bank of lights in a proscenium theater as seen from the audience. On the left a tree stump with a few leaves grows out of the band of earth, on the right there is a vibrant full leaved bush where the couple meets. Nature too gets younger.

This is a cinematic situation with the pool as a large geometric anchor. But the pool is slightly askew, or at least it appears to tilt downwards towards the right, a confusing error in the composition of the painting, a slight hitch in the newly acquired science of perspectival representation creating a constant disturbance in one’s ability to see the whole painting clearly, a kind of a punctum of instability within the straightforward left to right reading.

For me one figure stands out, because she is utterly specific and completely universal. We see her in every picture of a refuge camp around the world since the invention of photography. She is alone with her thoughts and her sorrows. She is most certainly real. Perhaps the whole painting is her dream of her youth.

I must leave this painting behind. I can’t take it back to New York.

But now, in another room of the museum another even more troublingly complex painting aims its arrow at me as I enter its chamber, Brueghel’s Netherlandish Proverbs. Again, as with the Cranach, it is hard to figure out what is the best distance or closeness with which to examine it, given the limitation imposed by the museum. Here is an overall composition even though, much as with the Cranach, most of the principal action takes place in the foreground, accessible through scale and proximity and the vagaries of lighting the work. I doubt if there is any perspective that would enable the total complete seeing of this painting. In this it is very much like one of my other favorite paintings, Ensor’s Christ Entry Into Brussels in 1889, which is filled with thousands of tiny figures, one of whom is Christ, but the viewer facing this huge painting mostly focuses on the life size sculpturally painted masked figures in the foreground. Ensor and Brueghel are intimately connected in their world view: fools abound, and the viewer also being a fool sees best what happens right in front of her.

The first figure that catches my eye does so because it is in the foreground, near the center, and also perhaps because it seems to have crawled out of paintings by another artist, Hieronymous Bosch. I come towards the painting to investigate further.

The picture above is taken off the internet. Everything is in focus and evenly lit. But this is not true of the situation for a visitor to the Gemaldegalerie, where reflection from the natural light filtering from the ceiling cut off some portion of clarity, re-enforcing the dominance of the figures in the foreground and middle ground..

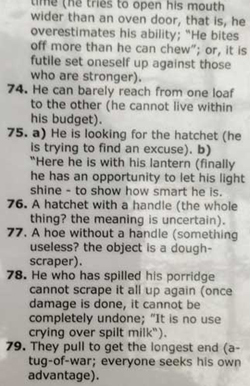

Three figures compel my attention. They are also in the front row, where I can see them well. Each wears a white smock, which makes them stand out in the crowd. They are, from left to right:

“He runs his head into a stone wall (to pursue the impossible recklessly and impetuously),” “To bang one’s head against a brick wall,” “To try to achieve the impossible”

“To fill the well after the calf has already drowned,” “To take action only after a disaster (Compare: “Shutting the barn door after the horse has bolted”)”

“He can barely reach from loaf to the other (he cannot live within his budget)”

I am particularly drawn to the figure on the left and the right, that is to say the two figures whose faces we cannot see. They are more abstract and it is easier to become them than the figure in the center whose face I see, it is so particular.

Really one figure compels my attention, the figure at the bottom right, his attempt to reach between loaves of bread a kind of crucifixion.

Folly abounds everywhere all the way to the horizon. At first glance it seems as if the painting envisages a happy ending, and in a way it does, for the sun also represents a proverb, “Everything, however finely spun, finally comes to the sun,” also translated as, “Nothing can be hidden forever.” But nothing is hidden, the painter sees everything, under tables, behind doors, in the attic, in the toilet, under water, in the far distance.

I am interested in how these two paintings are composed since they are populated with so many small figures.

Cranach’s composition is orderly and processional, and the fountain in the center anchors the painting in such a way that it takes another moment of attention to understand the transformation that splits the central form of the pool into two parts, the before and after of the transformation from age to youth. But soon you can follow the procession step by step. It’s a relatively easy tracking shot.

The Brueghel is a complex orchestration of chaos.The order and rationalism that one point perspective in painting represents is precisely the system of civilization which is being transgressed in very nook and cranny of city and country by human beings. Curiously, in another hall of the Gemaldegalerie, in the Italian Renaissance wing, that perspectival paradise is depicted in the Architectural Veduta (c.1490-1500), attributed to the artist and architect Francesco di Giorgio Martini, a painting of roughly the same dimensions as the other two, also ending in a seascape with a ship, but for spatial rationalism to exist and be presented, it is apparently necessary to remove all human presence. Absolute order is necessarily a world without fallible human beings, which means without any human beings at all.

Yet Netherlandish Proverbs is organized: it is like discovering the activities on a very large operatic stage design, when the curtain rises and all the extras and the chorus teem onto the center stage from trap doors, attics, cellars, spilling in and out and being positioned so that they can be seen from the audience even when they are inside a chamber of the scenery. If there was no set design, no direction they would all crash into each other and we wouldn’t make sense of anything. There is a general dynamically asymmetrical division of the landscape into the foreground of the town center, and a river that runs through hills and fields to a sea and the horizon. But it’s up to the viewer to take in all the details while at the same time trying to intuit the architectonics of the painting as a whole. Each instance of folly is so engaging that it distracts from conscious recognition of the underlying structure that holds the image together. It is a wild dance, a jumble, and a journey without a departure or arrival point.

This video is helpful in taking one through each proverb–some images represent two or three proverbs. It allows you to see details not easily discernible to the ordinary viewer. It is also interesting because the authors had to chose a path around the painting so they opted for a spiral trajectory. But a path is not given and in that sense it is one of the first all-over paintings of art history, one of the first truly modern paintings.

Note for my subscribers: if you are reading this post in your email program, please click on this link to see the video on YouTube, you will not be able to watch the embedded video in your email program. You can also watch it if you open this blog post online.

So, as my mother used to say in between thoughts, “So vot I vant to say?” Or have I said what I wanted to say about my experience in the presence of these two paintings which I fell in love with in Berlin?

I have left out much that can be said about these paintings, about their allegorical meanings and political goals. You don’t analyze all the constituent elements of the food you need, you just absorb them with gratitude. I need to see the Cranach again, I mean, I would need to be able to see it all the time, it must be seen in the flesh. It is a bewitching space, which cannot be experienced except by getting as close to it as possible. I also need to see it because I can’t make anything like it, or right now I wouldn’t be inclined to try, so I have to see the original over and over. The Bruegel I couldn’t completely see even when it was in front of me and it gained, for someone not of the original Netherlandish culture, from the linguistic guide, the graph, and the list of proverbs. Thus it is a linguistic experience and as such it is a conceptual painting, it is a conceptual experience which I can take with me. Now that I have seen the painting and know about it in that way of having seen it, the idea of it gives me a space where I can work from it, at the meeting of the figure, the idea, and the word, whether or not I ever see the painting again. Not to paint that, or like that, but to paint something that I’m already painting, but fueled by something new to me and gigantic.

These are not easy paintings to absorb or love or emulate, but they offer me a theory of the human.