Reading The New York Times Book Review section today, I was struck by the ironic twist implicit in one sentence of Jed’s Perl’s review, “Freedom of Expression,” of Gail Levin’s Lee Krasner: A Biography and Patricia Albers’ Joan Mitchell-Lady Painter: A Life. Perl writes of Krasner, “by the time Krasner met Pollock she was already extraordinarily self-aware. She had a profound grasp of modern art, deeper though less instinctive than Pollock’s, which she had absorbed through her studies in the 1930s with the great teacher Hans Hofmann.”

That is a bit of an over-simplification of the details of Lee Krasner’s self-chosen path to become a modern artist and an abstract painter–every path is self-chosen of course, but, as Levin’s book makes clear, as do many others about American art in the 1920s and 30s, in this period there was no clear academic or even social path for artists to realize this desire and many of the people who felt the calling of the modern in general and of abstraction in particular pursued every opportunity for enlightenment possible without much of an established guidebook. For Krasner, Hofmann was absolutely key–“I didn’t really get…the full impact of [cubism] until I worked with Hofmann,” & “the most valid thing that came to me from Hofmann was his enthusiasm for painting and his seriousness and commitment to it” (also, more touching, “Hofmann was the first person who said encouraging things to me about my work”) –however she tried several schools and made an effort to know everyone who could teach her something during more than a decade of courageous search.

Perl’s description relates an accepted view of Krasner: that she knew more about and was more articulate about abstract art than Pollock and was therefore able to assist him with theoretical /promotional language for what he instinctively embodied in his painting. Hofmann was a participant in the creation of this mythic image, since Pollock’s most frequently quoted declaration, “I am nature” was in response to Hofmann’s question, upon his first visit to Pollock’s studio (taken there by Krasner),”Do you work from nature?” In Levin’s account, Hofmann’s reply was sadly predictive: “You don’t work from nature, you work by heart. That’s no good. You will repeat yourself.”

Krasner’s knowledge and Pollock’s genius are an established narrative. And although genius always trumps intelligence, even conservative art critic Hilton Kramer was able to suggest a different reading of the same story in his New York Times review of the influential 1981 exhibition,”Krasner/Pollock: A Working Relationship,’‘ organized by Barbara Rose for the Grey Art Gallery at New York University:

“Yet Krasner, through her studies with Hans Hofmann, her interest in Matisse and other modernists who could not be assimilated into the social art movement, and her acquaintance with Gorky and de Kooning, was already launched on a more independent artistic course, and it was largely through her that Pollock was first drawn into the orbit of the modernist esthetic. (Pollock was not the only person to benefit from her guidance, by the way. It was Krasner who introduced Clement Greenberg to Hofmann and his school.) Part of the fascination of this exhibition lies in the account it gives us of the powerful influence that each of these painters exerted on the development of the other.”

Krasner indeed had years of intellectual, personal, and studio involvement with abstraction before she met Pollock. She even danced to boogie-woogie music with Mondrian! According to Levin, “She considered Mondrian one of her most outstanding partners for dancing. ‘I was a fairly good dancer, that is to say I can follow easily, but the complexity of Mondrian’s rhythm was not simple in any sense.’ ‘I nearly went mad trying to follow this man’s rhythm.'”..Well, in a way that story only restates the case of Krasner as the intellectual plodder to Pollock’s intuitive and nearly incomprehensible genius, but it’s a great story nonetheless.

What struck me in Perl’s casual formulation of the valence of self-awareness and knowledge versus that of instinct is how much of a twist this is on the usual gender stereotype of art historical canon formation: woman as instinctive and contingent, without language, man as intellectual and empowered by self-determination and theoretical clarity. “Instinctive” or “intuitive” is usually used to describe, and mark as lesser, work by women. “Women’s intuition” is commonly a trope for something less dependable and scientifically rooted than, presumably, men’s superior reason. Or, if she did it, it was just instinct, natural, unconscious, feminine, if he did it, he was able to productively channel his anima.

The exhibition, ”Krasner/Pollock: A Working Relationship,’‘ changed my view of Krasner’s work. The image, “good artist, but not as great as Pollock,” was challenged by the comparative chronology of abstraction in Krasner and Pollock’s work in the 1940s and particularly by the power and intensity of Krasner “Little Image” paintings.

Or, I should say that if while in general I have shared the commonly held view of Krasner as “good but not great” in the sense that her work doesn’t transform my understanding of what painting can be, the Krasner/Pollock show at the Grey Art Gallery troubled that conformist view in two ways.

First, in a field (Abstract Expressionism) dominated by an obsession with who did what first, Krasner’s so-called cerebral labor supported by her trio of influences– Cézanne/Matisse/Mondrian–seemed to have brought her to all-over abstract mark-making a moment before Pollock was able to fully break from the figurative social realism of Thomas Hart Benton and the surrealism/Picasso-influenced heavy symbolism of his earlier work to arrive at the all-over abstraction of his great works. And the image and the surface of the “Little Image” paintings are really intense, I find them exciting in general as well as the most exciting of Krasner’s work, so what is the role or standing of the category genius, when facing such paintings?

Also, although Krasner’s work was consistently involved with a cubism-based sense of architectonic structure, from the underlying grid of her “Little Image” paintings to her 1970s works in which she re-used cut up figure drawings from her Hofmann classes, Krasner seems to have changed course in a fairly contingent way. For all the intellectualism she gave to Pollock in support of his work, she seems to have followed unexpected urges for new directions in her own work in an instinctive/intuitive way rather than a structuralist/cerebral one, although the cubist infrastructure of her work was certainly always a given.

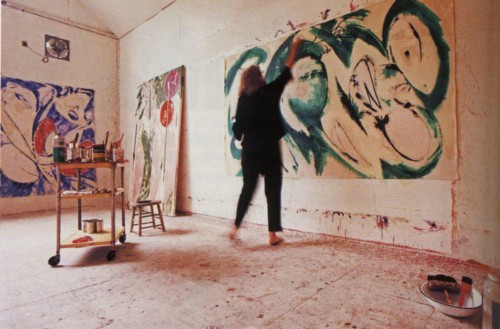

Levin’s book yields one wonderful image pertinent to this question of the intellectual versus the intuitive: apparently Krasner would jump up to produce marks at the top of her large canvases: “What I don’t want to do is get up on a ladder and hit the top. I want it to be within my body experience. I don’t want assistants working for me. I don’t experience it that way. I want to be in contact with my body and the work.”

Lee Krasner painting "Portrait in Green." Photo taken by Mark Patiky in 1969, from Gail Levin's "Lee Krasner: A Biography"

The images of Pollock in the act of painting are iconic representations which in some ways are as important and perhaps more influential than his work: his actions take us and art off of the field of painting into the performance of daily life and the actual space of the world. But here Krasner gets a moment of contingency and almost child-like joy for her involvement with the field of painting.

The two biographies join a growing bibliography of biographies of women artists. A few books of note:

Baroness Elsa: Gender, Dada, and Everyday Modernity-A Cultural Biography by Irene Gammel is an exemplary biography about the Baroness Elsa Von Freytag-Loringhoven (1874-1927) a fascinating figure of the early vanguard modernist period in Germany and the United States. Essential reading in tandem with this book is Amelia Jones’s Irrational Modernism: A Neurasthenic History of New York Dada.

To Paint Her Life: Charlotte Salomon in the Nazi Era by Mary Lowenthal Felstiner (every book that reproduces Salomon’s great autobiographical series of paintings, Life? Or Theater? is worth collecting. For those who don’t know her work at all, to say that she is painting’s Anne Frank is only the quickest historical placement for a major work by a young but trained and precociously mature artist, Life? Or Theater? is a great artwork, formally inventive, personally moving, historically significant as art and as historical record, a truly heroic work as well. I’ve linked to the most readily available version, but the 1981 Viking book and the 1963 version with an introduction by Paul Tillich mean more to me, the 1963 book, which I found in on the used book section of a small Provincetown bookstore, introduced me to this artist).

Remedios Varo:Unexpected Journeys by Janet Kaplan. A really interesting book about the Spanish-born Mexican artist not well enough known in the United States.

Paula Modersohn-Becker: Her life and Work by Gillian Perry. Another wonderful early-Twentieth century vanguard modernist painter not well enough known in the US.

Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo by Hayden Herrera. This is a very good book, well-written and with very good description and analysis of Kahlo’s paintings. Believe it or not, there was a time when there was no Kahlo industry, this book in a way initiated it. The only thing I can’t stand is that the original book cover with a self-portrait by Kahlo on it has been replaced by a photo of Selma Hayek as Frida Kahlo, from her film portrayal of the artist. The movie was enjoyable but that cover is a travesty. Still, the book is terrific.