The most sustaining force in an artist’s life is supportive friendship with other artists. If at some crucial moments in your life you can form a group of close friendships with artists who share your aesthetic ideals or at least understand and enjoy them maybe even more than you do yourself, you can make it through the incredible difficulties of being an artist: financial peril, near constant rejection, fragility of success. If those friendships also are the basis for artistic collaboration, that is more marvelous still. And there is a particular kind of collaboration among artists who are friends that is special because it takes place outside of the frame of the art market, often before each individual’s path is fixed and their fate is determined, that is before some become rich and famous, while others struggle along, and still others die or vanish from the scene into another type of life than the one of the artist. Such moments are nearly impossible to sustain, but it can be pretty conclusively proven that these are often the happiest times in the lives of these artists and often too those artworks that later are seen to have the greatest market value emerge from just these moments of friendships and creative projects undertaken in relative conditions of anonymity, for the sheer joy of making and the pleasure in shared ideas.

One such a web of creative friendships among visual artists and writers working in the mid-20th century in New York City, in a close yet liminal social and generational relationship to the New York School, is documented in a wonderful exhibition currently on view at Tibor de Nagy Gallery, Painters and Poets. This exhibition celebrates the 60th anniversary of the gallery, founded in 1950 by two men with diverse backgrounds–Tibor de Nagy, a well-born but impoverished Hungarian-born refugee banker, and John Bernard Myers who had been the managing editor of the avant-garde art and literary quarterly View.

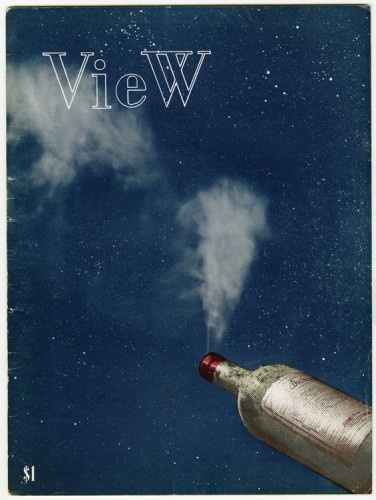

View, March 1945, cover by Marcel Duchamp

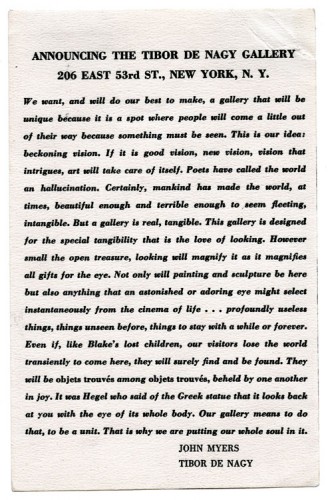

Tibor de Nagy Gallery, Inaugural Statement, 1950

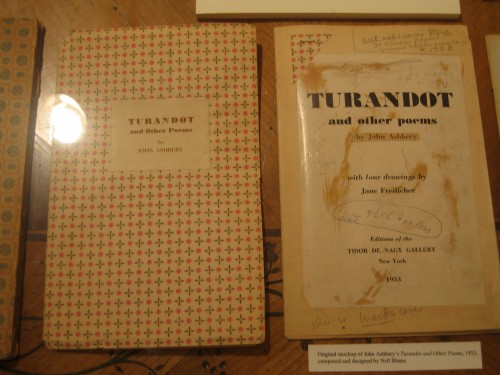

The unique characteristics of the gallery were already marked by its prehistory: de Nagy and Myers had just founded a marionette company which failed when parents kept their children away from public spaces during the polio epidemic of the time. Both men were interested in poetry, the artists who quickly merged into the gallery’s stable were intimately connected with poets, and the gallery began publishing small illustrated chap books and other incunabulae, many of these on view in the current exhibition.

One such work is Joe Brainard and Ron Padgett’s series of small collages collected as the work S, included in the exhibition. In his marvelous book Joe: A Memoir of Joe Brainard, Padgett describes their daily life during the time they produced this work, in a small apartment on East 88th street where Padgett and Brainard, childhood friends from Tulsa who had come to New York around 1960 lived with Padgett’s wife Pat. At the time Padgett was in college at Columbia and Brainard was an unemployed artist.

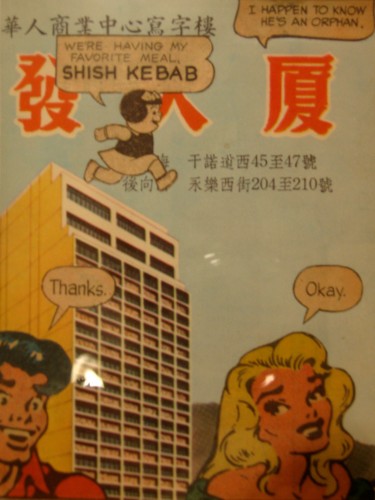

Joe slept on our living-room couch. Neither he nor I cooked, and Pat was sketchy in the kitchen herself. Breakfast was coffee and, on good days, a Pop-Tart….While I was in class and Pat at work, Joe roamed the city, especially the art galleries, museums, and junk shops, usually alone, sometimes with Ted [Berrigan], and on weekends with Pat and me. There wasn’t enough room in our apartment for him to set up a work space…. It was on Eighty-Eighth Street that Joe and I did a series of small works that we called S. The name came from a flat, metallic gold s that one of us glued onto the lid of a small pasteboard box, the kind that greeting cards come in, and into which we placed the finished works. These were on pieces of cardstock, typing paper, and tracing paper–drawings, words, and collaged material, much of it rather cryptic and hysterical, some of it erotic, some of it with images from Dick Tracy, L’il Abner, and Nancy comic strips. Our working method was highly collaborative; that is, Joe provided some of the words and I provided some of the images. Using the limited media and materials at hand, we worked spontaneously at a table in the living room, passing the pieces back and forth, drinking coffee, and smoking. Joe and I were twenty-one and goofy. Pat was a few years older and far more pragmatic, but she joined in on a few pieces. Over four or five such sessions, we ended up with around seventy works, some good, some puerile, some good and puerile. (Padgett, 61)

Joe Brainard and Ron Padgett, cover of S, 1963 gallery installation snap shot, Tibor de Nagy

Joe Brainard and Ron Padgett, S, detail, 1963, collage

This may describe an archetypal young artist’s narrative, but it also outlines a situation rather different from the present: Padgett and Brainard moved into a New York artworld where the circles were smaller, more interconnected and accessible, they could survive safely on less money, relative to current economic conditions, and Brainard could become a respected even beloved artist with only the self-education of the city streets and of looking on his own at lots of art, with no institutional framework or timetable except deeply felt personal necessity.

“Painters and Poets” celebrates and tracks a number of crucial friendships from these interconnected circles of artists and poets, some of which were also love affairs, sometimes sexual sometimes not: Frank O’Hara and Larry Rivers, Frank O’Hara and Grace Hartigan, Joe Brainard and Ron Padgett, Joe Brainard and John Ashbery, John Ashbery and James Schuyler, James Schuyler and painter and writer Fairfield Porter, Rudy Burckhardt and Edwin Denby, Rudy Burckhardt and Red Grooms and Mimi Gross, with central figures also including painters such as Jane Freilicher, Rackstraw Downes, Neil Welliver, Yvonne Jacquette, and Alex Katz.

Each of these artists were ambitious and dedicated artists in their own right and could legitimately claim to be at the center of some aspect of the group, and yet the interplay and the productive collaborations were an important part of their creative life. The current exhibition covers this fertile dynamic, with the orbit of Frank O’Hara shifting to the orbit of Joe Brainard, to the orbit of Rudy Burckhardt.These interlinked circles of friendships have been the focus of a number of exhibitions in the past decade or so, all interesting and inspiring: “In Memory of My Feelings: Frank O’Hara and American Art,” initiated at LA MOCA in 1999; “Art and Friendship: Selections from the Roland F. Pease Collection,” (Tibor de Nagy, Summer 1997); “Rudy Burckhardt” (also at Tibor de Nagy, June 2000), “Rudy Burckhardt and Friends: New York Artists of the 1950s and 60s,” (New York University Grey Art Gallery, May 9-July 15, 2000); “Semina Culture: Wallace Berman & His Circle” (Grey Art Gallery, January 16-March 31, 2007), and “New York Cool: Painting and Sculpture from the NYU Art Collection” (Grey Art Gallery, April 22- July 19, 2008); and also in 2008, “Picturing New York: The Art of Yvonne Jacquette and Rudy Burckhardt” at the Museum of the City of New York.

Fairfield Porter, Jimmy and John, oil on canvas, 36 1/4" x 45 1/2", 1957-58

Larry Rivers, Frank O'Hara, c. 1955, detail, plaster, 15 1/2"x7 1/4"

Many of the artists represented in the show and many long represented by the gallery, including Fairfield Porter, Freilicher, Burckhardt and others, worked in a vein of representational painting that was intimate, almost awkward, diffident, yet done with knowledge and experience of the just waning movement of Abstract Expressionism. Their works are among those that led me to suggest a category of “Modest Painting,” where ambition for painting is not dependent on huge size or even oppressive ideological rhetoric. As noted by painter Rackstraw Downes, Tibor de Nagy was one of a group of galleries which offered an alternative to the rapidly consolidated official art world of the late 50s and 60s:

To see this, the official art of the 1960s, you tramped Madison Avenue beginning at Emmerich and ending with Castelli. But there was another route which some people took, it included Frumkin, de Nagy, Zabriskie, Schoelkopf, Peridot, Graham among others. In these galleries one saw an art which looked awkwardly inexplicable; like so much of the liveliest art of any time it eluded critical dialectic. By the official art world it was virtually dismissed. And so I would call it the “unofficial” art of the 1960s. This was the world which interested me. It was the only art of quality that did not seem stage-managed; it had no party platform, no campaign. It did not bully you into believing that it was “right,” a condition impossible to art and which, when claimed by a school or a critic, automatically makes the art seem slightly suspect. …In 1964 John Bernard Myers, in an article called “Junkdump Fair Surveyed,” called this art “private.” [Downes, “What the Sixties Meant to Me,” (1973) 17]

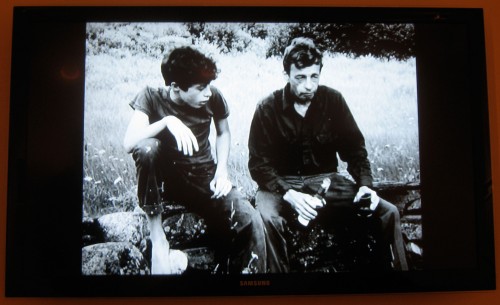

Rudy Burckhardt, Money (1967), screen shot, Edwin Denby and Money Tree

Many of the individual and collaborative works reflect a casual, relaxed approach to creative life underscored by ambition for art and an understated perfectionism. They were serious yet playful and playfulness was not the unique property of youth but a cross-generational process, engaged in by artists who were 19-year old newcomers to New York and people in their 50s and 60s, sophisticated veterans of the New York artworld like Burckhardt and Denby. My favorite piece in the show at Tibor is Burckhardt’s Money, (1967), his first feature film of his 100 or so films, with script by Joe Brainard, about a money mad billionaire played by Edwin Denby, a film which combines a goofy, spontaneous home movie feeling (with actors including Grooms, Gross, Jacquette, Welliver, Downes, as well as these artists’ children, Jacob Burckhardt, Titus Welliver, and Tom Burckhardt–now all adult artists engaged in film, acting, and painting) with thrillingly beautiful scenes with the cinematic quality of Jean Renoir, the neorealism of Roberto Rossellini, sly riffs on the contemporaneous Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and Jean Luc Godard’s Week End (1967) — there are also cinematic parallels to the spirit and the style of scenes going back to the anarchic speed of early Fatty Arbuckle and Buster Keaton or Hal Roach silent shorts and to films from the 1960s such as the one in Agnes Varda‘s Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962) in which a short comic slapstick silent film staring Godard and Anna Karina reenacting how they met (cute) interrupts Varda’s poetic reflection on mortality. There are so many scenes that stay in my mind from Money, not just the ones where I get a kick out of seeing people I knew when we were all young and younger, but just for their cinematic beauty: a boy running down a country road in Maine to recover a single penny he dropped, Denby planting a money tree, and floating up to the sky in a kind of dream of a death where you can perhaps take it with you. [Money has recently been preserved and digitally restored by the Anthology Film Archives in New York and will be screened February 25 and 26]. Of Money, Denby wrote: “The characters are all pretty bad, money is the root of evil, and they ought not to enjoy themselves, but they do anyway.” You will too.

Rudy Burckhardt, Money (1967), Jacob and Rudy, screen shot

[I should add that I am in some small way a member of the artworld family I’ve just described: my parents Ilya and Resia Schor were friends with Chaim Gross. I met Chaim’s daughter Mimi in my childhood and became friendly with her and her then husband Red Grooms when I was about 12. As soon as I began to navigate the city on my own on the subway I made my way to their studio on Grand and Mulberry Street. One amazing evening in 1968 I met for the first time Rudy Burckhardt, Yvonne Jacquette, their small son Tom, Jacob Burckhardt, Rudy’s son from his previous marriage to painter Edith Schloss, and Edwin Denby — the first sight of these 5 very delicate, kind, and interesting looking people is one of those crisp snapshots that immediately are engraved in your mind as deeply significant–also that night I met the Kuchar brothers, George and Mike, and we watched their movies. A few months later I worked for Red and Rudy on a stop-motion animated film Tappy Toes (1969): incredible to me that I was paid generously (can’t remember what but it seemed very generous to me) basically to hang out with them and get to see how they worked, what they looked at, while doing a menial task of moving small paper cutout figures a fraction of a millimeter at a time frame by frame for Rudy to photograph. And many years later I still live within the ripples of this particular art world, it is not historicist, for many of its participants are still alive, and its influence continues in the work of new generations–my collaboration with Susan Bee on our journal M/E/A/N/I/N/G also connects me to her collaborations with poet Charles Bernstein, who in turn has collaborated with Mimi Gross, and so on. The connections are many and they are important because the values of this world, in important part because of the connection to poetry (less money in this branch of the creative world), are always a vital corrective to the international Art Industry of museums, art fairs, which is as it appears, a capital-oriented and generally impregnable fortress. Within it creative friendships still exist of course, though time, play, and friendship are monitored and monetized in such a way that it can constantly erase the parallel universe of the artworld that Painters and Poets celebrates. ]