There seems to be almost as great an interest among the New York art community in the reviews of the New Museum’s recently opened Triennial exhibition “Songs for Sabotage” as there is in the show itself. I am not the first to note the reviews themselves as news: Sharon Butler did so as well on her blog Two Coats of Paint even as I was working on this text. So to start by reviewing some of the reviews, in order of appearance:

In his piece “The New Museum’s ‘I Am More Woke Than You’ Triennial,” online @Vulture.com, Jerry Saltz feels that the curators of the exhibition, the New Museum’s Gary Carrion-Murayari and Alex Gartenfeld, deputy director and chief curator of the Institute for Contemporary Art in Miami, are committed to a kind of academic orthodoxy in which artworks are chosen for and the wall texts structured to “name-checking the heady litany of issues shows like this always address: systemic oppression, Western hegemony, economic injustice, migration, homophobia, racism, sexism, colonialism, and postcolonialism,” and, further, that these choices are meant to indicate that “I Am More Woke Than You.”

Saltz is put off by the elitist academy-bound vocabulary used to promote the work, language evoking a set of references that might be obscure to the average viewer—which could be problematic in the buttressing of work for which the claim is being made that “the artists in “Songs for Sabotage” propose a kind of propaganda, engaging with new and traditional media in order to reveal the built systems that construct our reality, images, and truths” and that “The exhibition amounts to a call for action, an active engagement, and an interference in political and social structures.” However Saltz appreciates many of the artworks that he feels are effective aesthetically and emotionally, including in traditional media such as painting, despite whatever the rhetoric applied to them. Another major point of his review is his wish that the curators had looked to local artists, who may in some cases be less privileged, or at least as entrapped by current political and social structures, than the artists selected from the exhibition, despite their residences in often multiple cities around the world.

In his review on ArtNet, “How the New Museum’s Triennial Sabotages Its Own Revolutionary Mission–What’s all this talk of propaganda?,” Ben Davis zeroes in a number of basic disconnects between the domain of the political and the domain of art that is visible to and made visible by art institutions. He notes that “Surveying the concerns of an international art scene is a perilously immense brief.” Any major survey exhibition is always nothing more than a subjective snapshot of the cross section of culture that any curator or set of curators was able to gain access to at any given moment and certainly a true survey or inclusivity of contemporary art by a new generation is a basic impossibility, given that there are millions of artists globally and out of these and even among those under 38 or is it 33 or is it 30, there certainly must be any number doing interesting work in every visual and technical language available to artists today and most likely among these shall we say thousands many artists may be excellent, unique, and original in very similar ways.

Davis notes some of the same things that are the basis of Jerry Saltz’ criticism of the show, including the reliance on the insular language of academia in the wall text and catalogue, linking to another text on Artnet that he coauthored with Caroline Goldstein, which is a crib sheet for terms such as “the undercommons” that Saltz derided as obscure and elitist.

Davis finds it amusingly contradictory that the “undercommons” as proposed by Stafano Harney and Fred Moten “is, in part, an attack on professional “critical” academics in favor of a new celebration of non-professional, un-professional, or anti-professional knowledge as a form of intellectual civil disobedience,” while in fact “the show has the same sort of dutifully dense wall text that bedevils biennials of all kinds.”

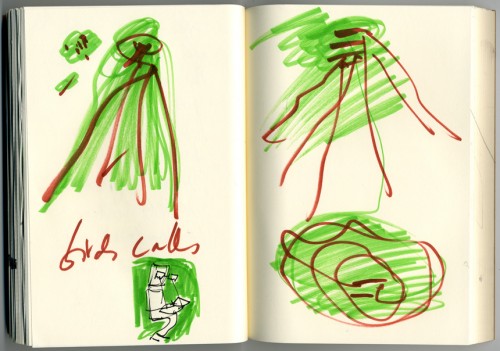

His principal focus is on the agenda articulated by curator Alex Gartenfeld that “one of the questions underlying ‘Songs for Sabotage’ is how art, ‘if successful might operate as propaganda.’” Davis seems to feel that this would be a worthy aim (propaganda understood here, I believe, as truly politically effective messages within artworks for a good cause) but that the work in the show mostly fails that standard by being more images or tropes of political propaganda rather than the real thing. In this he points to the same quote by Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci which art historian Benjamin Buchloh used as the epigraph to his attack on the resurgence of figurative, allegorical painting of the early 1980s, “Figures of Authority, Ciphers of Regression: Notes on the Return of Representation in European Painting” : ”“The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum, a great variety of morbid symptoms appears.” The quote appears high on the wall of an installation of large allegorical figurative social realist surrealist drawings by Anyupam Roy, a member of the Communist Party from New Delhi. In 1984, the “morbid symptoms” were the rise of Neo-Expressionism and other betrayals of the uniform direction of vanguard modernist abstraction, which, significantly, are also part of the visual used by Roy in these large works.

In his review in the New York Times, Holland Cotter feels, as the newspaper headline indicates, that the “New Museum Triennial Looks Great, but Plays It Safe.” In Cotter’s view, despite the show’s claims and “good work, real discoveries,” “in a politically demanding time, the show keeps its voice low, acts as if ambiguity and discretion were automatically virtues. In an era when the market rules, the show puts most of its money on the kind of work — easily displayable things — that art fairs suck up.” As part of that, Cotter notes the amount of painting and analogue objects. Cotter feels that even many of the artworks that lay claim to be dealing with political activism and resistance ultimately fall short in their political acuity and that the works do not “propose change,” preferring “political indirection.” Even artists who are proposed as examples of real world political activism, such as Roy, don’t seem to pass the test of creating truly revolutionary art, art that would serve as positive propaganda for a revolutionary situation.

Peter Schjeldahl, reviewing the show in the New Yorker, shares some of the critical views of expressed by Saltz and to some extent Davis, feeling that while “The work of the twenty-six individuals and groups, mostly ranging in age from twenty-five to thirty-five, from nineteen countries, is formally conservative, for the most part: lots of painting, and craft mediums that include weaving and ceramics,” while “The framing discourse is boilerplate radical.” Noting the curators’ use of the word propaganda as inherently a good thing, ““Art is a part of the infrastructure in which we live and, if successful, might operate as propaganda,” Schjeldahl places his view of that premise in parenthesis: “(If art is propaganda, propaganda is art—and we live in Hell.)”

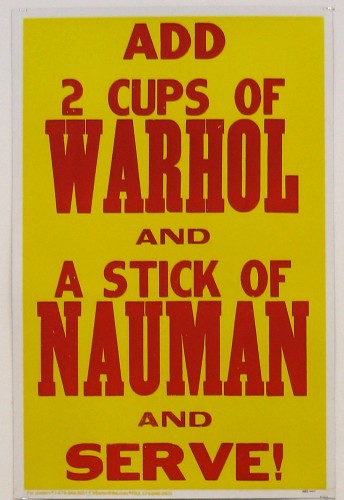

Having reviewed the reviews, I do not wish to write a review of the show. Co-curator Carrion-Murayari has stated that “As an exhibition series, the New Museum Triennial has historically promised to speculate upon the influence and voice of young global artists,” and in 2009 the first “Generational” triennial’s exhibition’s title was “Younger Than Jesus,” a title which served to infuriate everybody over 33 who had not yet had the privilege of being included in the city’s longer running series of Biennials at the Whitney. To echo Cotter’s observation, of course these are the kind of shows that the art market—galleries and fairs—sucks up, with media, gallerists, collectors, and curators inevitably trawling for break-out new stars. Cherrypicking from Felix Bernstein’s scorching critique of some of the rhetoric surrounding the last Triennial at the Museum in 2015, Triennial: Surround Audience, whose catalogue emphasized the radicality of millenial poetry, “even those claiming to be critically outside of it or romantically outside of it seem to be glued to its platforms, canons, and sales pitches. They are right, in one very crucial way: the work they are curating and putting forward sells to the public like candy.”

A show can be genuinely transformative of something—not the body politic at large perhaps but something—but even then stars will be sought out and some will be made. So there may be a built in contradiction in the Triennial’s focus on youth as the source of a new commodity while at the same time a course of propaganda for revolutionary activism.

And taking Walter Benjamin’s doctrine of “unintentional truth” as a guide–that “Truth is the death of intention” and “cultural objects [become] ‘a medium for the unconscious history-writing of society,” artworks and ephemera from a past time reveal ideological truths about their time period precisely in the unintentional, the blind spots of ideology that are lurking in the most taken for granted givens of a society’s imagery and methods–the curators’ claims that “The artists in “Songs for Sabotage” treat art as a form of propaganda that turns images on their head in order to reveal the ideologies and build worlds behind them” and that they “offer models for dismantling and replacing the political and economical networks that envelop today’s global youth” begin to falter. And are not all of us of many ages who are still working with art and ideology also enveloped in the same political and economical networks?

For me the best way to experience the current triennial was alone—that is, without a friend of my own generation with whom I could risk falling into generational cattiness (my students found it hilarious when I said this to them since it confirmed what they fear their elders think) and without a younger artist whose admiration for one work or the other might be enlightening but might also provoke generational jealousy. I also am fully aware that I am not the target audience for the show, not being a collector, curator, or even conventional art critic.

As I went around I checked the wall text to get a basic idea of who each artist was, where they were from, in some cases just basic information about what I was actually looking at, and then I looked at the work, and then if I was either puzzled or intrigued went back to the wall text to see what claims were made for each artist. Let me put it another way, some works caused me to stop and look before I attempted to read the wall text or “didactics,” sometimes because I liked the work, sometimes because I didn’t. I let the work rest lightly on my consciousness but gave the work perhaps a bit more time than I normally would an average individual gallery show.

In sum I did what probably was the most inappropriate to the stated priorities of the curators, which was to bracket the word propaganda with raised eyebrows, and respond to the work formally and stylistically, while trying to be as open as I could to both the ineffable and the ambitious as I found them.

Dalton Paula, Enfia a faca na bananeira, 2017

For example I spent the most time with paintings by Dalton Paula from Brazil: I was drawn to these curious horizontal diptychs representing a few basic objects and representations—plants, a bunch of bananas, a glass, a knife, a pair of scissors represented as representations in a frame–on a flat, flatly painted, soberly colored ground, part basic horizon line landscape, part bare bones representation of floor meeting wall, each bisected by the thin line where two canvases met, marked by a plant or object in the center of the composition. They were odd and curious, yet beautiful and intriguing. The wall text explained the source of the imagery in Brazil’s history of slavery and in the history of the search for rare botanicals with restorative properties. These historical subjects may well be a source of these paintings’ sense of gravity but the same wall text with the same cultural information could have accompanied less interesting work. These facts were informative without adding or subtracting from whatever it was that made me want to spend time looking at the works and did not alter my response to the paintings as a painter.

I had a similar reaction to Zhenya Machneva’s woven images. The materiality and pixillated surface and the warmth that the weaving technique imparted to the imagery and style with Picabia-esque representations of machinery, and a de Chirico-esque metaphysical quality was refreshing. These historic references may seem to diminish the work, but on the contrary they are meant as descriptive locators and they are part of the inescapable way that I process imagery, recognizing what an artist has done to re-envision something that existed before.

Zhenya Machneva, Project: Edition 1/1 “Apollo and pigs,” 2015. cotton , linen, synthetics.

On the other hand wall text can effectively quash criticality. As one example: I spotted some figurative paintings which immediately struck me as examples of a kind of work I have marked as being part of a subgroup of “Trite Tropes,” persistent styles and clichés usually not acknowledged by anything remotely part of the art establishment vanguard. In such paintings, figurative and narrative, many of which emerge from BFA and some MFA painting programs in the US, in direct contradistinction to what one feels is straining for individualism, for some reason everyone always seems to look alike, people even all having the same nose, from artist to artist.

On slide juries over the years I confess that I’ve usually eliminated such works, as have whoever were my colleagues, but this year in a similar situation I found that contemporary art conditions, including the massive return to a “return to order” of figuration with pathos, made it necessary to slow down and examine each such work with more care to see if markers of redeeming self-criticality and meta-stylistic content were present. And here was such a nose, as well as what seemed like a highly established faux naive outsider artist style of representation.

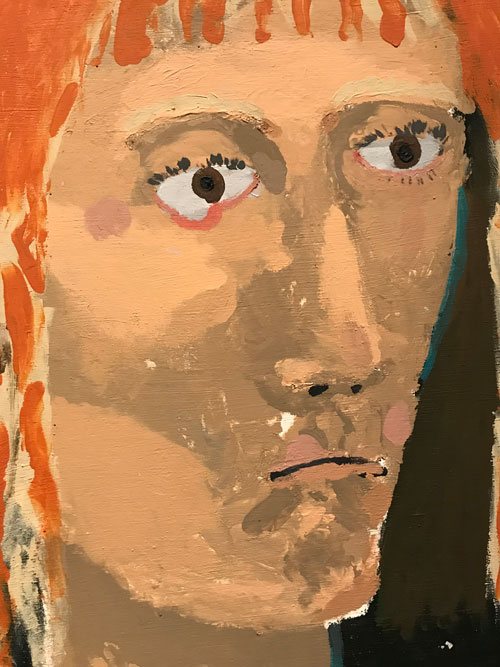

Manuel Solano, I don’t Know Love,” 2018. Acrylic on canvas.

But then I read the wall text which informed me that the artist, Manuel Solano, from Mexico City, was legally blind as a result of poorly treated HIV/AIDS. Such information–illness, tragedy, inspiring creative defiance of physical impairment–effectively forecloses on criticism–and that painting grows on me while remaining naggingly familiar, but, also, as Jerry Saltz wrote, his “heart broke a little,” not, I suspect, as much because of the work as because of the story.

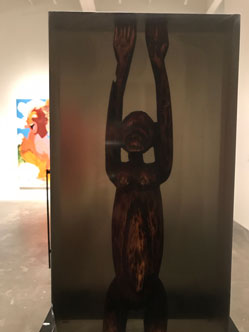

In the same room, I spent a different kind of more reflective time with Matthew Angelo Harrison’s African sculptures encased in resin, a visual device that I felt simultaneously could become a gimmick but that was quite haunting. They were beautiful and creepy, the metaphor of the entrapped figures crept up on me through the stillness and the allure of the materials.

For myself as an artist whose work has political intent in its narrative content and its materiality, and, I believe, its political content, whether evident or at the very least as subtext, I am under no illusions that my works even at their most specifically polemic or overtly satiric make any direct objective difference to a specific historical situation and one can count very few works that might be seen to have made even a symbolic impact on the politics of the time in which they were made, for a variety of reasons. This is particularly true if they are made in resistance to the power structure of the time–thus Diego Rivera’s murals in Mexico City were made as government sponsored public art and his mural series Detroit Industry was commissioned by the Detroit Art Institute– the only work of his that was contextually controversial, his Man at the Crossroads at Rockefeller Center, which included a portrait of Lenin, was destroyed by its sponsor, Nelson Rockefeller, before it could be seen by the public and is only known to us due to stealthy documentation by supporters as the destruction order was received. Manet prudently did not exhibit his Execution of Maximilian series in Paris in his lifetime, James Ensor’s Christ Entry Into Brussels in 1889 was rejected for exhibition by his own artists’ association and not exhibited publicly until 1929, long after the specific local political event that inspired it. Those works have certain characteristics of propaganda art, being based on actual news events, engaging in a critique with actual political and religious power, as well as challenging the contemporary norms of their artistic disciplines, but they were not effective as propaganda and one can argue that they could not have been under the historical conditions they were made. Their contribution to human culture is another story.

After seeing the show at the New Museum and reviewing the reviews, I happened to sit down with Leon Golub’s 1997 book of collected writings, Do Paintings Bite?, and it became clear that taking from these writings one could construct another review of Songs of Sabotage’s ambitions for what it calls propaganda and what some of its critics feel is just more art.

I recently assigned some excerpts from Do Paintings Bite? to students currently enrolled in a class I have hopefully, aspirationally, experimentally called “Painting as politics”—the students are a mixed group of mostly undergraduates who were equally intrigued by the novel notion of pairing painting with politics and their desire to take any painting class that is offered by the institution in any given semester. As the students and I have discovered it is not such a clear cut thing to teach since students have very diverse levels of ability and experience with the basic mechanics of painting and drawing and differing relationships to the political. They seem to have been impressed with the Golub exhibition at the Met Breuer, even genuinely moved and motivated by it.

I thought about Golub’s work and the way capitalism has, relatively speaking, failed to absorb it in the way it has, for example, embraced Francis Bacon, to name an expressionistic figurative artist of the generation that immediately preceded and overlapped with Golub.

As I have noted in an earlier post, which I put forward here as my review of Golub’s work though not of his current show at the Met Breuer, Golub was often disrespected by major art institutions despite his fame and repute and while New York-based reviewers jumped on reviewing the New Museum’s Triennial within the 24/7 news cycle, there has yet to be a review in the city’s paper of record The New York Times of Golub’s Met show which opened a few weeks ago, even though his work offers exactly the kind of transformative political engagement that Songs for Sabotage and some of its reviewers seem to call for, albeit in the form of painting when painting seems to be assigned by some of the reviewers quoted above to conservativism and commerce while new media is associated with contemporaneity and activism. His work was a form of sabotage, flaying the pristine surface of the Grand Tradition of Western Painting and of the modernist and post modernist agendas of major art institutions of the late 20th century, and, apparently, it still sticks in the craw of art history .

Golub writes:

The history of the 20th century is in large part a record of war, violence and atrocities. This is not of course the only history which is recorded but nevertheless it is extraordinary i both its virulence and in its wide spread extensions…Artists have recorded these conflicts over the millennia, most typically in celebration of the feats of power of rulers and national entities. Much of the history of at illustrates these events and celebrations. It’s very possible that many of the painters and sculptors who describe wars and feats of arms may have found their subject matter difficult or even repugnant but in its appearance, the art usually does not indicate this….I have pictured some of the events and some of the kinds of experiences that undercut our current world pictures, that is to say the effects of power and domination, the use of interrogation to control dissidence or opposition, how such behaviors effect the consciousness and psychic responses of victimizers and victims and also to indicate some of the public and private behavioral gestures of men acting out reactive scenarios….despite the apparent pessimism of negativity of the subject matter in the very reportage, in the very reporting of all this, there is retained a residual optimism in the very freedom to tell, that is to make and exhibiting these paintings. (from “Catalogue Statement,” 1996, in Do Paintings Bite? p.31)

That is, most art work is a reporting of the actions of power, serves power, and power does not encourage or support criticism of it, so the position of the artist is always in relation to what freedom is allowed, or to what extent the artist is willing to be excluded from reward.

Where is the artist as hero/anti-hero going to take his stance? Please note that this statement is being made on male terms with all the cynicism that that involves. Where are the artists and polemicists who can view Rwanda, Somalia, Haiti, Bosnia? …. How much more difficult for artists today to lay claim to a conscience that cuts through the controls, hypocrisies and willful ignoring of events that one would rather not face up to,, even as we are media-drenched in confrontational and/or collapsing situations….So what is our “commitment” or “committed art” going to be? A great question for the future but a negligible penetration into the “real.” (from “Out of Control? Beyond Our Grasp,” 1994, in Do Paintings Bite?, pp32-33., 1994

“A great question for the future but a negligible penetration into the ‘real'”could indicate the failure of even the “committed” artist, the political artist to really address the “real,” but in the context of reading it against the frame of claims for propaganda for the artists in “Songs of Sabotage,” it also seems to point to an inevitable gap between the task of “reporting” the effects of power and the penetration of such efforts into “the real” of the power system of the art world and market.

Considering himself in the frame of “Nationality,” as an American artist, Golub has the self-reflexivity to wonder.

“In actuality, however, I can’t say how much of a dissident I am. There is a relative openness to our society, for all its contradictory impulses; the great majority of American artists can pretty much do what they want, although they can starve while they are doing it.In a more nakedly controlled situation, things are different. For example, in China, in Tiananmen Square, attempts to loosen such control were destroyed by state power….Would I be a dissident in another situation? maybe I would try to be subtly subversive or maybe I would be a lackey of the system: I don’t know. I can’t say I’d be a hero because I haven’t been tested.” (Symposium, 1991, from Do Paintings Bite? p.43

The texts in Do Paintings Bite? are organized in reverse chronological order, an interesting and disruptive device, putting the concerns and aspirations of the younger artist to the test of his later questions and conclusions while giving his initial agenda the last word. The third to last piece is “Buchenwald and Elugelab,” a wall statement for an exhibition at The Artists Gallery in New York in 1954. It is interesting to end here with wall text, so important to the exhibition at the New Museum and its critical reception, but in this case by the artist–that would be interesting perhaps, to return the museum “didactics” more overtly to the artists (although this could also be a disaster!).

Golub concluded his statement with an assertion in capital letters:

THE CREATIVE ACT IS A MORAL COMMITMENT TRANSCENDING ANY FORMALISTIC DISENGAGEMENT.

You expect him to write, FORMALIST ENGAGEMENT. “DISENGAGEMENT” indicates that even if the work includes within its project a modernist critique of its discipline, that’s not enough to serve as activist propaganda for a social political cause. And even if the artist makes a moral commitment to a social cause, that may not be enough either to actually effect change in the real world. And yet it can have political meaning and import.

I highly recommend Golub’s show “Raw Nerve” currently at the Met Breuer.