The first issue of M/E/A/N/I/N/G: A Journal of Contemporary Art Issues, was published in December 1986. M/E/A/N/I/N/G is a collaboration between two artists, Susan Bee and Mira Schor, both painters with expanded interests in writing and politics, and an extended community of artists, art critics, historians, theorists, and poets, whom we sought to engage in discourse and to give a voice to.

For our 30th anniversary and final issue, we have asked some long-time contributors and some new friends to create images and write about where they place meaning today. As ever, we have encouraged artists and writers to feel free to speak to the concerns that have the most meaning to them right now.

Every other day from December 5 until we are done, a grouping of contributions will appear on A Year of Positive Thinking. We invite you to live through this time with all of us in a spirit of impromptu improvisation and passionate care for our futures.

Susan Bee and Mira Schor

*

Note to email subscribers: the videos in this post can only be viewed if you are online, they will not run in your email program.

*

LigoranoReese

Nora Ligorano and Marshall Reese collaborate as LigoranoReese. Their body of work includes public events, videos, sculptures, installations and limited edition multiples. They installed their most recent installation The American Dream Project in Cleveland and Philadelphia during the political conventions.

*

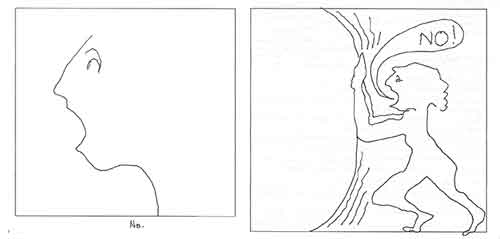

Joy Garnett and Bill Jones: “No”

Joy Garnett, “Yellow Scarf,” 2016. Oil on canvas, 12×9 inches

Video: Bill Jones, No, no. 2016, music video animation (1:16 minutes)

Joy Garnett is a painter and writer living in Brooklyn, New York. Her most recent solo exhibitions were held at Slag Contemporary in Brooklyn, NY and Platform Gallery, Seattle, WA. Bill Jones is an artist and performer who lives and works in Brooklyn, NY. Jones was a seminal figure in the Vancouver School of conceptual photography along with such artists as Rodney Graham, Ian Wallace and Jeff Wall.

*

Aviva Rahmani: Blowin’ in the Wind

No. NO. NO!

About hope or solace now, I know very little.

After 50 odd years of an art practice, I still believe the answers are in art.

This is the fast phase of climate change, accelerating geometrically.

The planet will adjust to over-consumption dispassionately.

In 2007, for the “Weather Report,” show at BMCA, the paleoecologist Jim White and I used regular recordable desktop sharing sessions over a period of several months to analyze stress on global biogeography (the aggregation of living and non-living systems in the landscape, and their relationships to each other). In a series of maps, using Google Earth and Photoshop, we layered that information with data about population concentration, resource depletion, and the probable effects of increased climate change on those regions, with particular attention to sources of fresh water, or as a threat to human populations from sea level rise or extreme weather. Our conversations were about what elements needed to be prioritized based on scale and drama of impact, for example when drought leads to geopolitical disruption in Egypt or the Sudan, due to competitive conflicts over water loss, or how sea level rise in Bangladesh or the Gulf of Mexico would lead to a likely trajectory of massive human migrations to other parts of the globe, as I drew real time into the maps on the screen. This applied raw material into a transdisciplinary complex adaptive model (a way to study disparate agents in relationship to each other based on how complexity theory works) to determine predictive results (i.e., subsequent events in Sudan and Egypt).

In 2015, I realized the only solution to impending global ecosystem disaster was to stop using fossil fuels immediately. So then I designed The Blued Trees Symphony, copyrighted installations in miles of proposed natural gas corridors, intended to challenge eminent domain takings with sonified biogeographic sculpture.

I knew it would be hard to be the kind of artist I intended to be, but I didn’t know how many ways I could trip over myself. The confusions I feel are more complicated now than they were fifty years ago.

I thought more people would respond when we all yelled, “fire!”

I pay more attention than ever now to formalism.

The sun still sets and rises with exquisite clouds.

Indigenous practices inspire me.

If I’d known how much writing it takes to survive as an artist, I would have paid more attention to grammar when I was eleven.

I detest banality but realize in retrospect how often it has seduced me.

Sometimes I cry.

I still love snow as much as I did when I was three.

Small joys, blessings and miracles give meaning to life.

The grand surges of joy and inspiration make life worthwhile.

I wish travel were easier. I’m writing on a late flight from Denver to New York City. The pilot just asked us to please tell him how the crew could make our flight more enjoyable. I think he has to be kidding. Let me count the ways. Let’s start with isolating the man with the bad head cold sneezing in the seat next to me and calming the crying baby.

So, I’m coming to the end of my life, in a handful of years or a couple decades. I intend to go out as fiercely as I came in.

Beauty and love will always stir me.

We are all grasping at straws in a tornado now.

I think we must be like bamboo bending in the wind, trusting our roots in common soil.

Thank you both for making this frame for our thoughts to be shared.

Aviva Rahmani’s The Blued Trees Symphony was awarded a 2016 Fellowship from the New York Foundation for the Arts (NYFA). Her “Trigger Points/ Tipping Points,” premiered at the 2007 Venice Biennale, and contributed to Gulf to Gulf (2009- present), a NYFA sponsored project accessed from 85 countries. Rahmani is an Affiliate with INSTAAR, University of Colorado at Boulder.

*

Aziz + Cucher

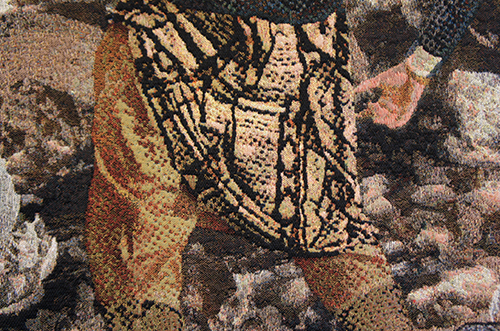

Aziz + Cucher, “Some People,” cotton tapestry, 74” x 124”

Aziz + Cucher, Some People, tapestry, detail

Aziz + Cucher, “Some People,” tapestry, detail

In 2002 we had a sort of epiphany when we encountered the first of two extraordinary tapestry exhibitions at the MET called Tapestry in the Renaissance, a survey of northern european tapestry production between 1460-1560, curated by Thomas Campbell. This show opened our eyes to the rich tradition of pictorial storytelling embodied in these woven masterpieces, and it challenged us to conceive of ways in which our own practice as artists in the XXI century might embrace allegorical narrative and materiality as a way to represent contemporary battlefields and geopolitical conflict.

Aziz + Cucher—Anthony Aziz (b.Lunenburg, MA) and Sammy Cucher (b.Lima, Peru). Anthony and Sammy have been living and working together since meeting as graduate students in 1990 at the San Francisco Art Institute. Their projects have been exhibited and published widely, including shows at The New Museum, New York; Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid; Photographer’s Gallery, London; Fondation Cartier, Paris; Nationalgalerie Berlin; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Aziz + Cucher are recipients of a 2015 New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship in Digital and Electronic Art. They are both members of the Fine Arts Faculty at Parsons School of Design /The New School in New York City and recently were artists in residence at the Frans Masereel Centrum in Belgium where they worked on a series of prints as well as a set of digitally woven tapestries in collaboration with Magnolia Editions based in Oakland, CA.

*

Erik Moskowitz + Amanda Trager

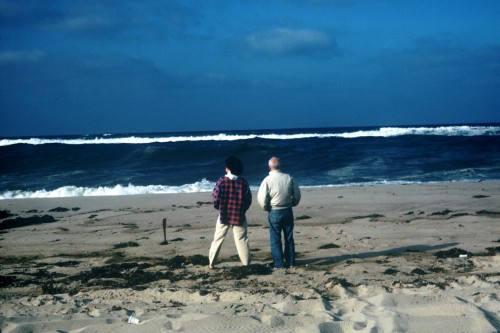

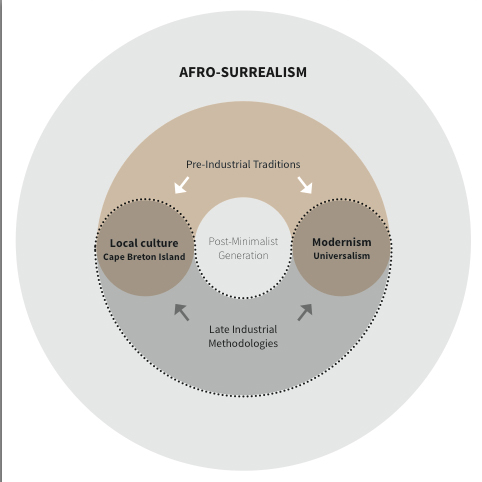

Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Canada is a location that is central to our lives. We have spent time there each summer since 1999. Over the years we’ve created narratives that utilize the location but we have not, up until now, referenced Cape Breton explicitly in our works. Erik originally came there in the mid-70s with his family and an extended community that included creative luminaries such as Joan Jonas, Philip Glass, Richard Serra, JoAnne Akalaitis and Rudy Wurlitzer, all friends and collaborators from the downtown art world in New York City.

Until the 1970s many families in Cape Breton, with twenty or so children, lived without modern plumbing and electricity. It is still fairly common for people to raise crops, fish, trap and hunt for sustenance, build their own structures and heat their homes in winter by hauling wood from family lots. Because of Cape Breton’s remoteness, its local traditions have abided to a remarkable degree — until recently.

Due to the ever-increasing need-for-speed of neo-liberalism, global trade and environmental degradation, the days of traditional living are waning. High-speed internet (widely introduced just four years ago) and world-class golf courses augur a move towards homogenization, materialism and hierarchy. Moreover, the summer artist community’s post-minimalist practice — Modernism’s last act — also appears to be terminal in its urgency and agency.

It appears that we are at a tipping point.

Witnessing this change and conveying what Cape Breton and its people mean to us now carries an urgency that we could not have anticipated before the horrible realities of Trump’s rise. In moments of gratitude and in our worst nightmares it exists as a place of refuge. The generation of artists and back-to-the landers that arrived there in the ‘60s and ‘70s might have thought of Cape Breton as an emergency escape hatch, but that idea has now perhaps been subsumed by the contemporary world-order.

We’re moved to consider Cape Breton Island within the realm of the symbolic, and to consider its alternatives within a speculative framework. If we can agree that the current situation feels like science fiction, we can then posit that a science fiction has the imaginative capacity to define answers to the planetary dilemmas we currently face.

In this we are guided by the science fiction of Octavia Butler and her reformulations of kinship structures. While anticipating how various oppressions increasingly structure lives and worlds, she simultaneously delineates emancipatory understandings of family that upset the usual barriers presented by race, gender, class, and age.

Discovering and developing connections between these disparate narratives constitutes the work of this project, offering possibilities for re-considerations of the role of culture in spiritual and emotional survival beyond the maintenance of bare life. Because expression is necessary to survival, not an addendum to it. Feeling already flung into an era of rapid destabilization on many fronts, this sentiment must now be considered within the context of a long view, and with a hopeful eye towards imagining identity in terms of dispersion and dissolution.

Erik Moskowitz + Amanda Trager, “Island,” video still (work in progress)

Erik Moskowitz + Amanda Trager, “Afro-Surrealist chart,” 2016

Erik Moskowitz and Amanda Trager are collaborators who make film and installation works. Both were born and raised in New York City. Their work has been shown at venues that include the Centre Pompidou, Participant, Inc, Museo Reina Sophia, Beirut Art Center and Haus Der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin.

*

Michelle Jaffé: Soul Junk

Who’s in Control? © Michelle Jaffé 2013-2016 from Michelle Jaffé on Vimeo

Who Makes That Choice? © Michelle Jaffé 2013-2016 from Michelle Jaffé on Vimeo

SOUL JUNK is a 1, 2 or 3-channel video / audio installation that explores raw emotions, power & intent conveyed & betrayed by the human voice & facial expression. SJ places people inside a mind at work.

To view these works in full screen mode please go here for “Who’s in Control?” and here for “Who Makes That Choice?”

Emotionally raw confessions about family trauma are juxtaposed with observations about the cocksure attitudes of those in power. Authority is assumed to be right. However, just because it holds the seat of power, does not make it so. In Soul Junk, I was compelled to move through my own understanding of power structures & an individual’s power grab in the age of the selfie. How those systems get played out in the family, through power brokers, government, and corporations. I process narcissistic & patriarchal behavior through the rhythm of my own lens in an effort to understand the political, economic and ethical landscape of our time. Those in power often prevail at the expense of individuals, families, & communities.

When & where are the borders between terror, abuse & negligence blurred & crossed? How do personal behavior, corporate & national interests, & armed terrorist groups drive politics? I expose my pain, doubts & frustration in an effort to make sense of the world we live in and to stimulate conversation for change. Soul Junk is a catalyst for social justice.

Michelle Jaffé creates sculpture, sound and video installations, immersing people in an experience that transforms their sensory awareness. These participatory encounters create a moment where a synaptic shift in attitude is possible and new neural connections can be made. Her work has been exhibited at Duke University- Power Plant, Beall Center for Art + Technology at UC Irvine, NYCEMF, Morlan Gallery at Transylvania University, KY, Bosi Contemporary, NY and UICA, Grand Rapids. Solo exhibitions at Bosi Contemporary, Wald & Po Kim Gallery, Susan Berko-Conde Gallery, Brooklyn College, Harvestworks Digital Media in NY, among others. Since 2008, Jaffé has been a fiscally sponsored artist of the New York Foundation for the Arts.

*

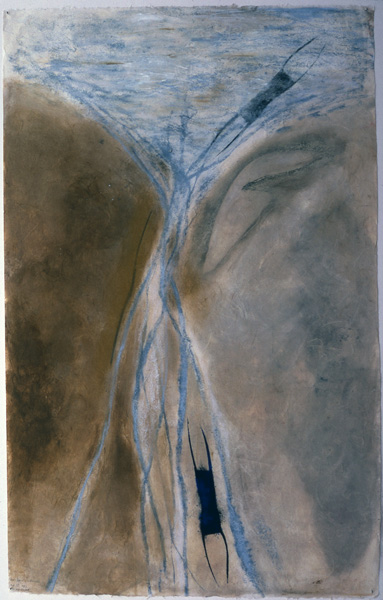

Hermine Ford

Nov. 22, 2016

Dear Mira and Susan,

Today I had lunch with Mira and saw some shows together in Chelsea. The kind of day that old friends who are artists often share. Did it feel “normal”? No. We talked about the art we were looking at, we talked about how neighborhoods have changed. We talked about growing older. And we talked about the election. We looked back over other “the worst of times” in our lives: WWII, the assassinations of JFK and MLK…both felt like the end of America. And of course 9/11. As an artist I need to do my work in order to be coherent and functional in other areas of my life. I need also to feel my friends, my community around me. I hope that my work makes a contribution to them, but I can’t depend on that. I need to choose when I will participate in group actions to defend democracy, and I need to make a more specific contribution by volunteering to help open the swinging door that would enable very young people to walk into my world of reading, writing, making art, a doorway into a big wide world full of adventure and deep beauty, and through which I may have the privilege of entering their world. This is my survival plan for myself and I am grateful to M/E/A/N/I/N/G for always having provided a place where these kinds of musings can be shared.

Love,

Hermine

Hermine Ford, “Yellow Star,” 2016. Oil on cotton muslin on panel,

33 1/2″ x 41″

Hermine Ford grew up in NYC. Her childhood neighborhood was 23 St. down 2nd Ave. to Houston St and points east. She lives and works in NYC with extended stays in rural Canada and Rome. All three locations, in an annual roundelay, inform her work.

***

Further installments of M/E/A/N/I/N/G: The Final Issue on A Year of Positive Thinking will appear here every other day. Contributors will include Altoon Sultan, Erica Hunt, Jenny Perlin, Julie Harrison, Noah Fischer, Robert C. Morgan, Roger Denson, Susan Bee, Mira Schor, and more. If you are interested in this series and don’t want to miss any of it, please subscribe to A Year of Positive Thinking during this period, by clicking on subscribe at the upper right of the blog online, making sure to verify your email when prompted.

M/E/A/N/I/N/G: A History

We published 20 print issues biannually over ten years from 1986-1996. In 2000, M/E/A/N/I/N/G: An Anthology of Artists’ Writings, Theory, and Criticism was published by Duke University Press. In 2002 we began to publish M/E/A/N/I/N/G Online and have published six online issues. Issue #6 is a link to the digital reissue of all of the original twenty hard copy issues of the journal. The M/E/A/N/I/N/G archive from 1986 to 2002 is in the collection of the Beinecke Library at Yale University.