We were born in the safe interval between catastrophes. Which is worse? To have been born in a catastrophic moment and live life at all times informed by danger, fear, and the necessities of bare survival, or to have been born in a moment and place of relative safety and bounty. My generation, many of us the children of war refugees, Holocaust survivors, war survivors in Europe, or of survivors of the Great Depression, was steeped in the history of the previous catastrophic era, but we grew up in a golden moment of post-war middle class relative security and cultural possibility. Now darkness descends: fascism, austerity, poverty, war, extremism, the eradication of symbols of civilization by men and the eradication, by men, of the planet as a site for human existence. Is it worse for us born in an illusory moment of security or for those beginning their lives, born into a transitional moment of lingering entitlement but growing desperation?

Among responses to what happened yesterday evening in Paris, are shock, horror, grief, but also a condemnation of the West for its causative historical policies of colonialism and exploitation, its recent history of senseless war, and its lack of interest in anything that happens any place but at its core. Behind that lurks something else, a critique of the Enlightenment as the philosophical source of Eurocentric domination, something that one encounters more particularly in the one place that has any concern for the Enlightenment, that is to say academia. It is a contradictory discussion, whose terms are largely determined by Western thought, much of it emerging from Paris since the Seventeenth Century and particularly since the French Revolution. Last night the familiar meme, “Today we are all French, Today we are all Parisian…” began to appear, just as monuments around the world were illuminated in the tricolor of the French flag. And certainly anyone who critiques the Enlightenment, just as anyone who is interested in democracy, is going to use French thought to do so, which is to say, largely, Parisian thought.

I am not qualified to engage with the critique of the Enlightenment. But I did receive a French education. That was my “formation” (pronounced as the French word meaning education and training). I later turned away from it yet my mind was formed and marked by that education.

This morning I reached for some of the books from my education at the Lyçée Français de New York and then some of the other books that have been so central to so many of us.

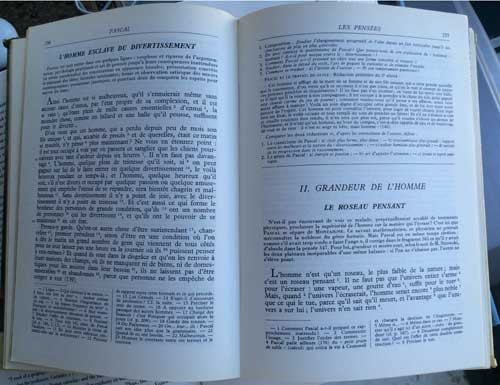

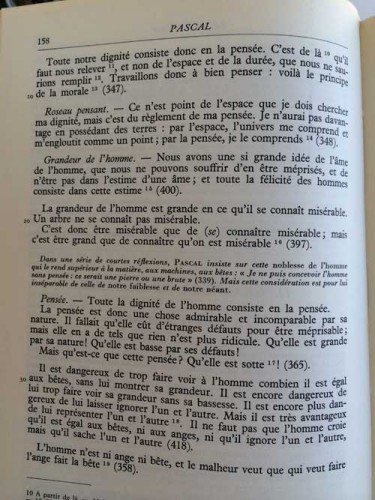

First I got on a little step ladder to get down from an upper shelf my trusty Lagarde & Michard readers from high school at the Lyçée. I loved these books. Do I remember anything from them enough to discuss or teach? No, and yet when I open them I see the work that we did every week, reading these texts, doing “explication de texte,” being formed by thought and a detailed approach to language about thought itself. They do place human thought at the center of the world. The text most frequently quoted by my students the past few years is Jane Bennett’s Vibrant Matter, where human agency and participation in events is decentered. This is an interesting and importantly egalitarian view, and yet the earlier human centered philosophy is still instructive and even necessary.

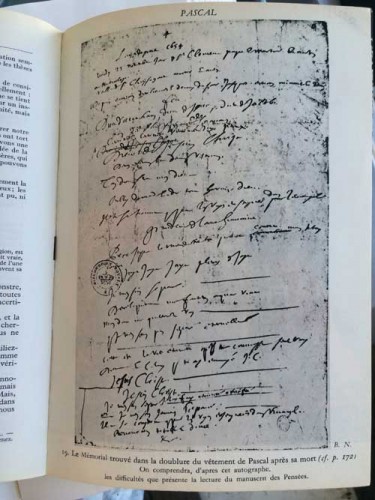

Yet here is Blaise Pascal‘s “Le Roseau Pensant,” which posits man as a frail thing, dignified only by his capacity to be self-aware of his mortality and to think. Below that, from the Lagarde & Michard reader, a holographic reproduction of a piece of paper found in the lining of Pascal’s jacket upon his death, the Memorial.

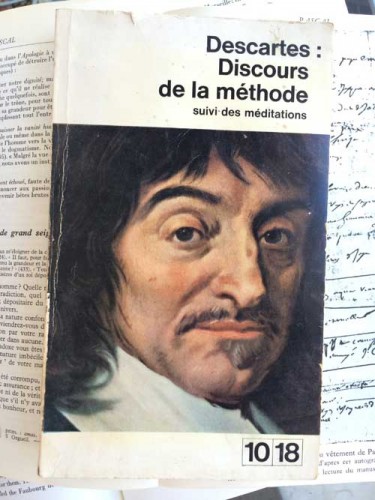

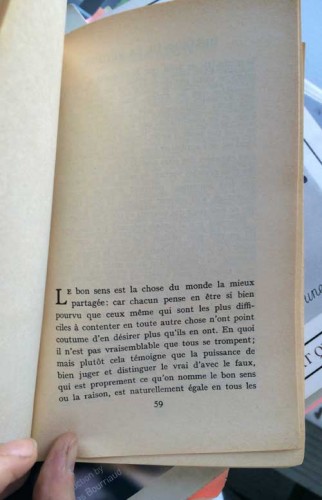

Below that I found two copies of René Descartes’ Discours de la méthode.

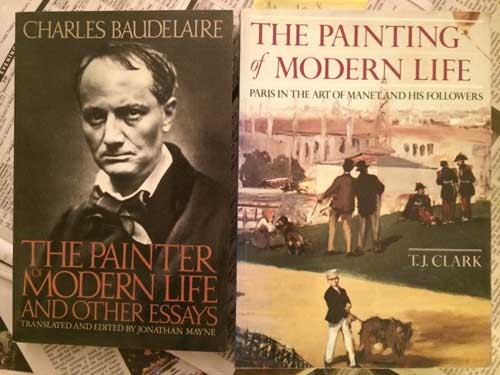

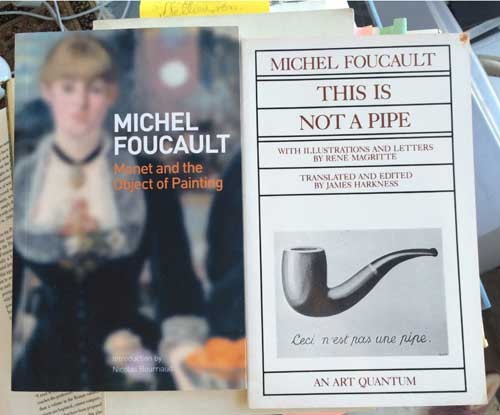

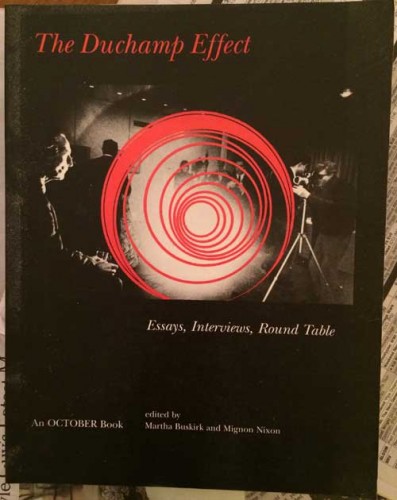

From my readings of the past three decades, in another part of my library:

My generation grew up into the spirit of 1968. It was our time. We lived Paris and its philosophy through the films of Jean Luc Godard and also in a different way those of François Truffaut and Éric Rohmer. The CalArts I attended in 1971, as I realized much later, represented the flowering, in America, of the spirit of ’68, in its approach to freedom within learning and teaching. Most graduate students today still read Debord‘s The Society of the Spectacle and thoughts on détournement are metaphorically traced over the street plan of Paris.

…and in this thread I am not even addressing the importance of French and French based visual art, but…

&

&

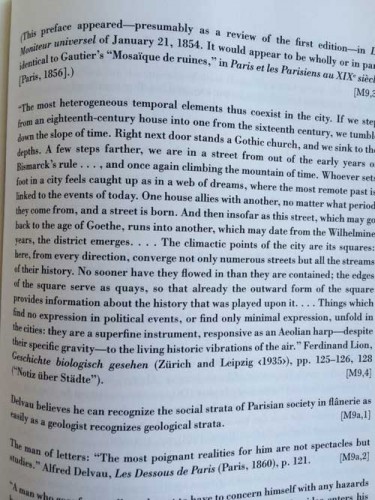

All graduate students in visual arts or media studies are assigned Walter Benjamin’s “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Mechanical Reproducibility.” Few immerse themselves in Benjamin’s Arcades Project, a massive, unfinished, mythical, collection of research about the early years of commodity culture studied through the cultural history of Paris in the Nineteenth Century.

I find that some things are hard wired to an extent that is surprising. I’ve never lived in Paris, have only spent a few weeks there my whole life, and for various reasons and tropisms I became as much of an Anglophile as my sister Naomi Schor became a Francophile, but its role in my parents life and in that of my sister–her red-covered arrondissement map of Paris was one of her most treasured possessions–and the particular role that it plays in the history of the civilization that was the focus of my education from first grade through the final year of the Lyçée, “Philo,” is evidently so deep that I feel a particular spike of hysteria and rage when I hear news of terrorist attacks in Paris. I feel rage at many of the violations of civilization that we experience, from the deep sin the USA committed in waging the Iraq War, for which we will pay for decades, to the destruction of Palmyra, to the near daily mass shootings in the USA. As it is, post 9/11, fear of terrorism inflects my movements in the city, and if that fear is realized in a manner like what has occurred in Paris and elsewhere around the world, I would be under the bed with fear. But apparently Paris occupies a special space in my imaginary.

My father Ilya Schor came to Paris on a grant from the Polish government in 1937. My mother Resia Schor joined him in 1938. Here they are that winter, Place de la République, near where one of the attacks in Paris took place last night.

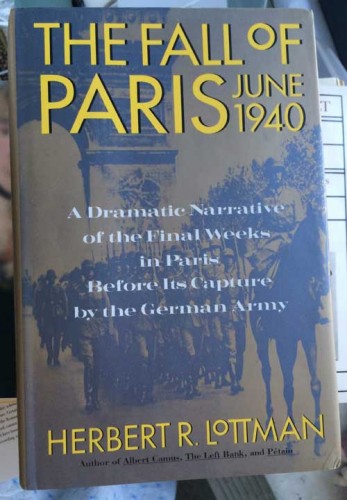

It is my belief that most likely they would have lived their life based in Paris, returning to Poland to visit family, if it were not for the war. They fled Paris in either late May or early June, 1940, a few days ahead of the German Army. One of the many things I forgot to ask my mother was which day, exactly. Her memory was excellent, particularly for those few weeks of their life, from their departure from Paris, by the Porte d’Orléans, on one of the last trains or the last Métro, then on foot through Orléans, down to Bordeaux, towards the Spanish border, to their arrival in Marseilles in August 1940, where they stayed until October or November 1941, then on through Spain to Lisbon, arriving in New York December 3, 1941.

There are some books I have, but perhaps this is the moment to confess I have not read them.

I will open to a page of Jacques Derrida‘s Archive Fever.

Through chance operations I find this paragraph, in which “the process of archivization” matches and is matched by “anarchiving destruction.”

The news from Paris is one of the many blows to our sense of the loss of reason and hope of our time, yet the day is followed by the day, and one has to figure out how to make the days count even if the idea of accumulating material for the human archive is increasingly revealed as a fantasy.