First, some quick comparisons among two current exhibitions in New York City and an exhibitionistic pop culture event, Otto Dix at the Neue Galerie, Greater New York 2010 at MoMA P.S.1, and Work of Art: The Next Great Artist on Bravo Network. You can have some fun imagining the portraits Otto Dix might have made of the panelists and jurors on “Work of Art:” after all, he specialized in turning even the most distinguished scientists and artists, including himself, into demonic characters. Take the strapless tight-fitting red satin mini-dress with big bow on the bustier which seems to be the template outfit in terms of style and color for the female hosts of reality shows on Bravo — China Chow on “Work of Art” and Kelly Choi on Top Chef Masters — I’m considering the advisability and semiotics of wearing such an outfit, with stiletto heels, of course, when I meet my new students at my first graduate seminar or core studio class next fall.

China Chow and the "next great artists"

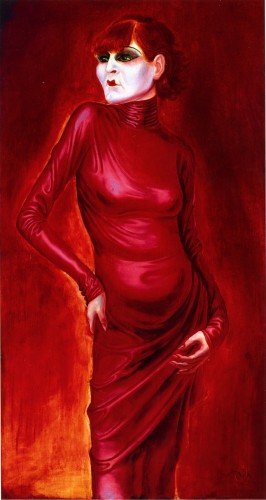

Now look at Otto Dix’s intense, garish scarlet red 1925 portrait of the noted and notorious Weimar-era dancer Anita Berber, note the triumphant sense of sexuality and style in her figure and, written on her mask-like face, sad features hidden under her stylized make-up, and her crisped left hand, the tragic self-awareness underlying this figure’s display:

Otto Dix, Portrait of the Dancer Anita Berber, 1925, oil and tempera on plywood, 47 3/8x 25 1/2 inches, Kunstmuseum, Stuttgart

It is easy to poke fun at a TV reality show. I watch it because it’s there; because it’s a pop phenomenon that may end up infiltrating the expectations of art students and affirming popular misrepresentations of how artists work and think; I want to know what happens next because that’s the nature of narrative; I enjoy Jerry Saltz’s weekly behind the scenes recaps up to that point only; and, all pleasantries and rationalizations aside, does anyone seriously think any one of the participants deserves a $100,000 prize, functionally one of the biggest cash grants to an individual artist in the world? Unreal.

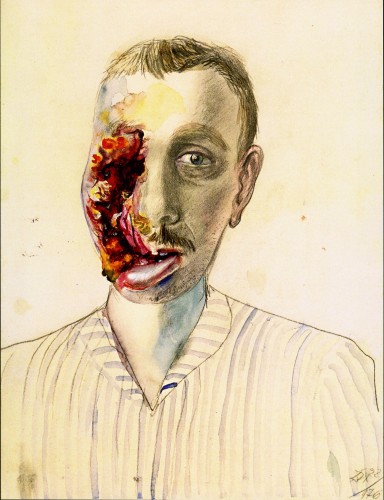

As for reality, here’s reality for you, distilled into a modest drawing of a man horribly injured in World War I: it’s precisely the delicacy and skill of the pencil rendering of the left side of the man’s face and the delicate water colored stripping of his shirt that make the equally delicately rendered watercolor gash that violates the right side of his face so subversive.

Otto Dix, Wounded Veteran, 1922, watercolor and pencil, 19 1/4 x 14 1/2 inches, Private Collection

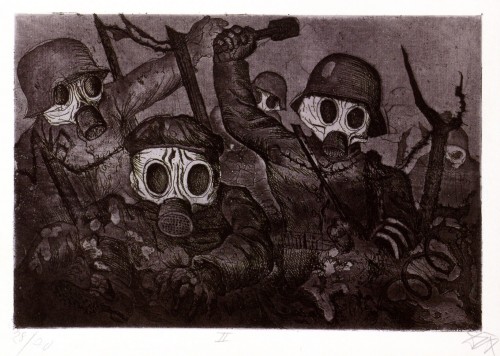

This drawing, along with a few other spare, beautifully executed, matter-of-fact gory drawings of human intestines and brains, is exhibited in a second floor room at The Neue Galerie dedicated to Der Krieg (War), a series of 50 prints by Otto Dix originally published in 1924. Don’t miss Der Krieg. There are many relevant art historical comparisons, notably to Goya’s Disasters of War, but it is also important to think of these works in relation to the wars we are currently engaged in, that we barely pay attention to and from whose effects on human bodies we have been shielded.

Otto Dix, Mealtime in the Trench, from Der Krieg (War), 1924, etching and drypoint

In fact don’t miss the Otto Dix exhibition at the Neue Galerie even though some of the work and most of the installation may be problematic.

I was just reading Carroll Dunham’s well-researched, fair assessment of this exhibition in the current Summer 2010 Artforum. He notes that it’s not a complete Dix retrospective since it leaves out all his post WWII production and some Weimar-era masterworks which were not available for loan and that the show is installed in a “garbled and out of focus” manner. It’s true that in a few cases the themes seem mislabeled and it’s a little hard to follow the logic of a very overcrowded installation. Dunham seems to be of two minds about Dix: having seen Dix’s work in “Glitter and Doom: German Portraits from the 1920s” at the Met in 2006-07 he was “convinced that Dix was an enormously important missing piece of the history of early modernism” but the current show leaves him an unclear picture of Dix’s place: “History was both with and against him, in ways far more vivid and direct than many of us ever experience,and the contingencies of fate have made it hard for us to accurately reconstruct his achievement.” In terms of Dix’s place in the history of twentieth century modernist painting, Dunham seems overly concerned with who Dix may have influenced, or, more precisely, with the validation of Dix by the admiration for or Oedipal interest in Dix’s work on the part of artists who Dunham considers important (he gives the example of Baselitz).

There are undoubtedly some issues with Dix’s work: a tendency towards the mannerist, the kitschy, and the misogynistic, maybe even, on the basis of recognized visual tropes at least, the anti-Semitic. But, as I read Dunham’s review, I thought, “Yeah but the place is packed with amazing, ridiculously intense masterpieces, and even the kitschy paintings pack more power than most work we see.”

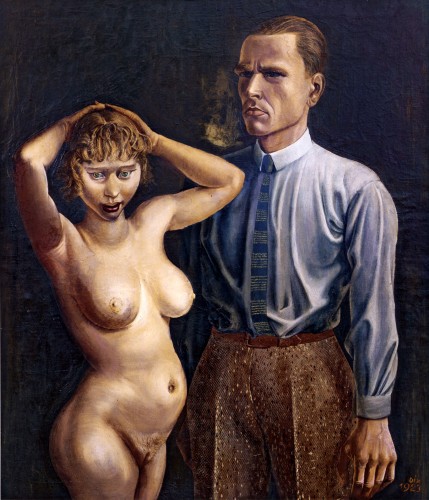

In fact, let me start with the kitschiest painting I can’t ever forget, Self-Portrait with Muse, 1924:

Otto Dix, Self-Portrait with Muse, 1924, oil and tempera on canvas, 31 7/8 x 37 3/8 inches, Osthaus Museum Hagen

Here the fully clothed, thin-lipped, stern-faced fair-haired male artist encounters an almost comically over-endowed, flamboyantly ethnic — whether Semitic or Latin — woman. He confronts her, he is confronted by her, as she raises her hand in a gesture which can be read as a greeting, a blessing, or a stoppage, a counter-action to the reach of his brush which is in effect creating her. She is hardly the passive creation of a Pygmalion and if you look at some of the depictions of women by fascist-approved artists of the same general period in Germany you immediately get what makes this painting so different and seditious even though it does portray a naked woman and a clothed man, a familiar theme in the history of Western representation.

Dix’s wild muse has an over-ripeness of sensuality and an extreme quality as a representation that more than equals his own and a specificity that makes it hard to think of her as an abject victim of the male gaze. Their meeting ground is the blank space of the painting surface itself, the lack of situational specifics giving this a mythological implication and, formally, a modernist undertone with a medieval subtext: this is a very flat painting yet closer in its spirit and its use of space to the flatness of Northern Renaissance painting, which is one of the main sources of Dix’s several painterly and graphic styles.

Dix’s Self-Portrait with Nude Model (1923) is less kitschy but perhaps more troubling because of the emphasis of the anatomical sexual representation and the dazed, blurry expression of the woman’s face. Dix is imposing as a figure here, but there is something strangely affecting and not entirely protected in his self-depiction, despite the military bearing under the civilian clothes.

Otto Dix, Self-Portrait with Nude Model, 1923, oil on canvas, 41 3/8 x 35 3/8 inches, Private Collection

Here I think it is useful to think of Dix’s self-portrait, his rigid, soldiery demeanor, in relation to the “soldier male,” the subject of Klaus Theweleit’s fascinating two volume study of the psycho-sexual roots of fascism in turn of the century Prussia, Male Fantasies –Volume 1: women, floods, bodies, history (published in German in 1977, University of Minnesota Press, 1987) and Volume 2: male bodies: paralyzing the white terror (published in German in 1977, University of Minnesota Press, 1989). Theweleit studies the memoirs and pulp fiction and films made by and for the officers of the Friekorps, private armies who fought battles of internal repression in Germany between the two world wars and paved the path for Nazism, in particular examining their violent sexual depiction of women, communists, and Jews. This analysis remains of great importance and relevance as a tool for understanding similar manifestations in our time.

I first used Theweleit’s books as a tool in my analysis of the gendered aspects of the critique of painting in my 1989 essay “Figure/Ground.” I would have to reread the books in order to draw out new quotes, which is tempting: I strongly recommend both volumes.

The “soldier male” (according to Theweleit’s term) has never fully developed “secure sense of external boundaries,” a pleasurable sense of the membrane of skin. He fears the “Red floods” — of the masses, blood, dirt, “morass,” “slime,” “pulp,” woman — which he perceives as constantly threatening to dissolve his “external boundaries.” He also fears the liquid forces insecurely caged within his own body interior and unconscious. The “soldier male resolves these conflictual fears by the construction of a militarized, regimented body, by incorporation into a desexualized phalanx of men, and by the reduction, through killing, of all outer threats back to the red pulp he images everything living to be. “He escapes by mashing others to the pulp he himself threatens to become.” (Mira Schor, “Figure/Ground,” Wet, 149)

[Cross reference this description with the recent fetishization in the press of General Stanley McChrystal’s hard body and self-mortifying spartan habits].

Otto Dix, Human Intestines, 1920, watercolor, 18 1/8 x 15 inches

In the first years after WWI, Dix sometimes provoked his friend “with his detailed description of the pleasurable sensation to be had when bayoneting an enemy to death” (Olaf Peters, Otto Dix, exhibition catalogue, Prestel: 2010, 96) but often spoke of the nightmares he had for years afterwards.

Otto Dix, Shock Troops Advance Under Gas, from Der Krieg (War), 1924, etching, ,

Describing the plot of one of these examples of Friekorps literature, Theweleit writes: “The central point of the construction of this murder is that the woman castrates the man. There is also the implication that she is a whore; the fact that she is the only woman traveling with six men is clear enough indication. The weapon she uses to castrate him is initially hidden; the pistol is pulled unexpectedly out of her apron, as if it were a concealed … penis? […] “It is a phallic, not a vaginal potency that is fantasized and feared.” (Vol 1, p. 72). Again, an interesting background to Dix’s many paintings of “lustmord,” sex murders.

, Despite the disturbing violence depicted in these works, I find in many of Dix’s paintings of women something other than misogyny: the humanity of the women is never sugar coated into pneumatic attractiveness in the vein of John Currin, who Dunham mentions in regard to Dix’s sources in Northern Renaissance Germanic and Netherlandish portraiture. To the contrary, Dix adopts the detailed, delicate surface and the often elongated, Gothic form and angular, spiky drawn lines of the Northern manner, to depict the deep drama of the women of all ages and stages of beauty, sexuality, despair and decay. Each is vulnerable, anxious, and mortal rather than only sexually available, and each is a character with an inner life, which to me takes the work away from misogyny.

Despite the disturbing violence depicted in these works, I find in many of Dix’s paintings of women something other than misogyny: the humanity of the women is never sugar coated into pneumatic attractiveness in the vein of John Currin, who Dunham mentions in regard to Dix’s sources in Northern Renaissance Germanic and Netherlandish portraiture. To the contrary, Dix adopts the detailed, delicate surface and the often elongated, Gothic form and angular, spiky drawn lines of the Northern manner, to depict the deep drama of the women of all ages and stages of beauty, sexuality, despair and decay. Each is vulnerable, anxious, and mortal rather than only sexually available, and each is a character with an inner life, which to me takes the work away from misogyny.

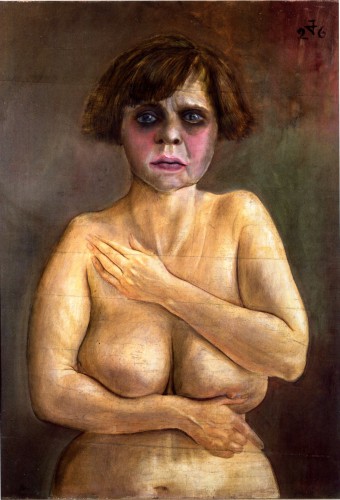

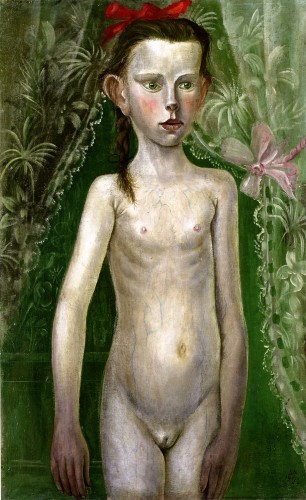

Look at the contrast between the way the anguished face, the imperfect body, and the delicately self-protective hands are depicted in Half-Nude. Look at the strange blue veins under the thin skin of the pre-pubescent girl, her femininity symbolized by the lace curtain and its pink ribbon, her sexuality by the red ribbon in her hair.

Otto Dix, Half-Nude, 1926, oil and tempera on wood, 28 3/4 x 21 5/8 inches, Private Collection

Otto Dix, Little Girl in Front of a Curtain, 1922, oil on canvas, 31 3/4"x20 inches, The Minneapolis Institute of the Arts

Hans Baldung Grien, The Three Ages and Death, c.1540, oil on panel, 151 x 59 cm, Museo del Prado

Dix represents in his work what the Friekorps’ violent pulp fiction and wan representations of the ideal woman and the “soldier male” sought to repress. Dix’s works were included in the Degenerate Art show organized by Hitler and Goebbels in 1937 [must see documentary about this exhibition]and one of the reasons he refused to leave Germany during the war was that he was sure his work would be destroyed if he left it behind (conversely the Jewish lawyer Hugo Simons took his portrait by Dix with him when he fled Germany with his family, an immensely risky thing since generally even in the mid-30s it was best to leave Germany with only the shirt on your back as if you were coming back the next day. This portrait is included in the current exhibition.)

Earlier I described Dix’s pencil and watercolor drawing of the Wounded Veteran drawing as “modest,” in the way that I have used the word modest in my essay “Modest Painting” to indicate work that does not seek to overpower the viewer by virtue of size or self-aggrandizing gesture but by its ambition for the medium itself and in this case by the subject matter represented, which is devastating, riveting, tragic, epic. I can add the obvious, but like everything in Dix’s work, it’s to the power of ten: Dix believed in drawing as he believed in painting as powerful vehicles for the transmission of meaning.

The most notable characteristic of work in this year’s Greater New York 2010 exhibition at MoMA P.S.1 is that there is little evidence of any trust in the capacity of a singular object or medium to carry meaning. Nothing is allowed to just be: nearly every painter hedges her bets and also hangs some blurry photo-montages or stick a few objects on a table, if there is a painting then there is also a video, and maybe a bench or two.

The most notable characteristic of the works exhibited in the Otto Dix retrospective at the Neue Galerie is that each painting or drawing or etching uses the specificity of each medium to transmit meaning and, boy, is that enough, because nearly every work is an atom bomb. Dix hedges no bets in the wretched human emotion and delicate perception and satire he packs into each work. Certainly some paintings and drawings go headlong into kitsch that is almost alarming, totally over the top, presumably dated in style, although nearly each of these also has something fantastic in it, and no matter what the emotion and the human content and even the handling of the material is 100% committed and fascinating. His work is pitiless, sometimes garish, yet his line is as detailed and delicate as a Flemish masterwork, his surfaces are varied and complex.

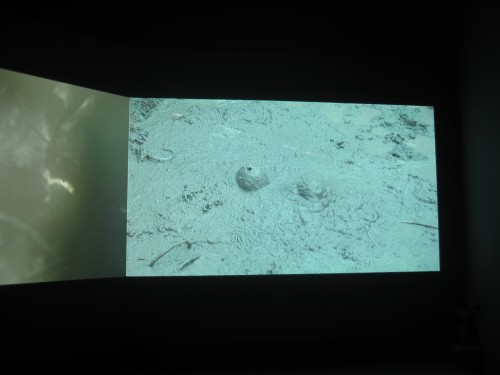

To continue the comparison between these exhibitions a bit longer, there are some tropes in Greater New York that Dix might appreciate — for instance, mud is a recurrent trope in Greater New York: this may reflect ecological concerns although often the mud seems like a metaphor for paint: instead of painting with it, you make a video of it burbling up, plopping down, it’s the original primal slime that no one has the patience to learn to discipline or trust in its expressivity). My notes from Greater New York include: “Alex Hubbard, 2 big paintings, frayed sides, 2001 A Space Odyssey monolith, projection of video of burbling mud, red benches, MUD, paint IS mud, primal goo;” “Gilad Ratman, 2 screen video, more mud.” I counted about 4 other pieces where mud or paint as goo and ooze (but in the disembodied clean form of video of course) was featured.

Gilad Ratman, The 588 Project, 2009, two screen video, Greater New York exhibition

When Dix painted the works in this exhibition, he too was young and extremely ambitious: even on the battlefield he was not only drawing on anything he could get his hands on, he was also keeping in touch with the artworld of his time and, as soon as he was demobilized if not before, making sure his work was included in the important exhibitions of the day. You can be sure that if he were a young man today, he would be putting his work forward with as much murderous ambitious as anyone but he wouldn’t be a contestant on “Work of Art: The Next Great Artist.” If at all, he would be one of the top chefs on Top Chef Masters: I watched the final episode of this year’s “Top Chef Masters” after the premiere of “Work of Art” and whereas the art “reality” show was interesting only as a manifestation of desperation — think They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? — Top Chef Masters was, relatively speaking, riveting. The judges were articulate and passionate, and, as opposed to some of the art jurors, they seemed to be better able to clarify the aesthetic criteria they were applying to the food — again, relatively speaking — either gnocchi are chewy or they’re not, the fish underdone or overcooked depending on your gustatory ideology — and the chefs were powerful characters, with compelling personal narratives that they had channeled into their work, and each finalist radiated physical and psychic power instead of play-acting self-puffery and abjection. I was particularly impressed by Hong Kong-born, Canadian chef Susur Lee and the winner, Ethiopian-born, Swedish-reared chef Marcus Samuelsson. These men were fearsome, awesome Ninjas, and Dix might have been one of them.

Dix’s inventiveness, his technical skill, and his attention to detail as well as his intensity of characterization and the fury at man’s murderous drives make each work almost ridiculously powerful. The show at the Neue Galerie is packed with one outrageous masterpiece after another, each atom bomb crammed unceremoniously close to the other, against the rules of modernist exhibition practices. While Greater New York takes a long time to get through because artists are given generous amounts of space, and because there are so many time-based works in dark rooms, in the mode of the day, the Otto Dix works are in rooms with dark colored walls that give a kind of old world feel to work that would appear totally contemporary in other circumstances, and his works on paper are in darkened rooms in order to protect them. To do many of the paintings and etching series justice you’d have to spend hours and hours and I hope people will do so. But I would also cast my vote for a Freaky Friday experiment: force the artists exhibiting in Greater New York to contend with a small space in which each work would have to intensely convey powerful meaning without relying on the luxury of excess exhibition space and give Dix’s works the modernist white cube treatment that would allow them to breathe and give them back the contemporaneity they exude, unbeknownst to most young art viewers in New York.