I wanted to make sure to see the George Bellows exhibition at the Metropolitan before it closes February 18, in order to see a few paintings that had been recommended to me by Susan Bee, in particular three paintings done between 1907 and 1909 of the excavation of the site for Pennsylvania Station.

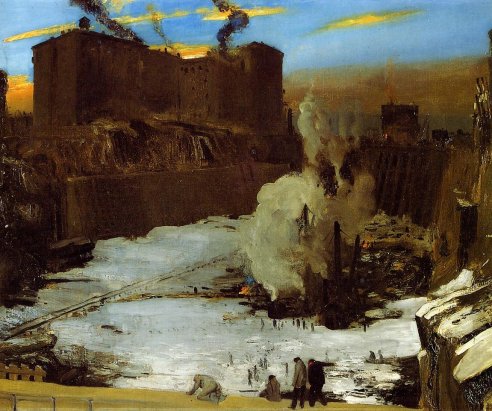

The paintings are easel sized and painted in a loose expressionistic style that is a eerie and awkward combination of Goya, Velasquez, Courbet, with a Brueghel quote in the bottom right corner of a dark worker against a snow white background but, despite these historical allusions, they are imbued with a regionalist, Americanist feel. And yet, as one viewer I overheard say, these paintings are ferocious. In the first, Pennsylvania Excavation, the organized city is a far off dream against the blackened rock, earth, and gravel pit covered by snow and white mist from the steam engine of a work train dwarfed by the scale of site.

George Bellows. Pennsylvania Excavation, 1907. Oil on canvas, 33 7/8 x 44 in. . Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts.

In the second painting, Pennsylvania Station Excavation (1909) the most hellish part of the dark excavation site is in a concentrated area devoted to the chaotic process of excavation and construction, relieved or at least punctuated visually by a startingly vibrant blue sky shot with peach colored cloud, in that way that cloud formations have of occasionally reminding New Yorkers that we live on a planet, so absorbed as we are in the urban environment that blocks nature and seems like a self-contained universe.

And the third painting in the series Excavation at Night (1908) though unfortunately over-varnished, particularly damaging for a very dark painting, but at the same time the shiny blackness of large areas of the work served to reinforce the connection I made between Bellows’ choice and treatment of this subject and Robert Smithson‘s observations on entropy in his 1967 essay “A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey.” Describing the “minor monuments” being built along the Passaic River, including

concrete abutments that supported the shoulders of a new highway in the process of being built. River Drive was in part bulldozed and in part intact. It was hard to tell the new highway from the old road; they were both confounded into a unitary chaos. Since it was Saturday, many machines were not working, and this caused them to resemble prehistoric creatures trapped in the mud, or, better, extinct machines–mechanical dinosaurs stripped of their skin….Nearby, on the river bank, was an artificial crater that contained a pale limpid pond of water, and from the side of the crater protruded six large pipes that gushed the water of the pond into the river. This constituted a monumental fountain that suggested six horizontal smokestacks that seemed to be flooding the river with liquid smoke.

Of these chaotic “monuments,” Smithson writes,

That zero panorama seemed to contain ruins in reverse, that is–all the new construction that would eventually be built. This is the opposite of the “romantic ruins” because the buildings don’t fall into ruin after they are built but rather rise into ruin before they are built.

Next to Excavation at Night is a slightly oversize reproduction of a 1915 tinted postcard of the completed Pennsylannia Rail Road Station, so we have a time line of the pit that was, the beauty that was, built to outdo and outlast the Baths of Caracalla but it also ended up having risen into ruin, and then looking back into the pit Bellows has documented in these paintings, we can place ourselves in the hellish chaos of the current Pennsylvania Station, something like a giant airport bathroom built with 1970s cheapness over the tracks of the original station.

These are very good paintings by a painter who was just short of being great–something about the way the figures are done, even his famous boxers where the figures are very dynamic yet too stiffly posed, the paint marks very bold in some cases, in other delicate and almost folk art like–there ‘s a very good portrait of an elderly couple from Woodstock that from 1924 that shifts around in an interestingly uncertain yet touching space between traditional portraiture in the European style, Renoir and Grant Wood. But he was nevertheless a very interesting artist, and he looked at interesting, important things, that is, the city as it was built, and as it was lived by the poor, and these paintings should be seen, especially as we celebrate the 100th anniversary of Grand Central Terminal, saved from demolition only as short a time ago as 1978, and thus mourn one of the greatest crimes in American culture and the history of New York City, the destruction of Pennsylvania Station, even as we anticipate what is shaping up to be as great a cultural crime, though a slightly less visible one, the demolition of the seven levels of book stacks under the Rose Main Reading Room of the New York Public Library for the construction of yet another airport mall style mediocre-looking space.