Elizabeth Murray: Painting in the 80s at Pace Gallery arrives at an interesting moment in terms of the abrupt shift of stylistic currents and tropes that characterize art history and it offers an opportunity to revisit the situation of women painters in the 1980s.

Brief study prompt: Painting in the 1980s–you weren’t supposed to do it–that is, if you were a woman, and especially a woman interested in discourse on gender politics. Different story if you were an American, Italian, or German man.

Or you could do it, although particularly if you were a male artist, but certainly not sincerely, there had to be an ironic twist. An appropriational basis in photography and language helped.

The title of the show implies the aesthetic tensions of that moment, that is, the title is not Elizabeth Murray: Paintings of the 80s, which would place the focus on her work alone during a certain time period of her working life, but Painting in the 80s, that is, her activity of painting in the 80s and, beyond that, the activity and the discipline of painting at a particular moment in Western art history.

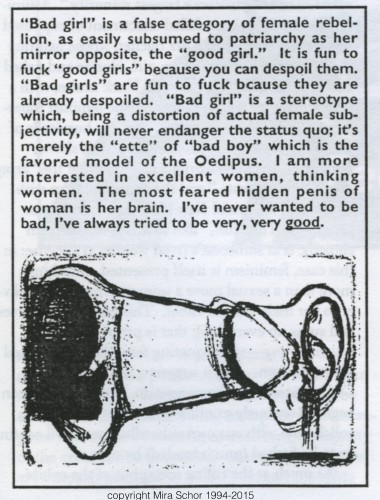

Starting in the early 1980s, the art market experienced a huge surge after a decade of relative recession which had been, not coincidentally, marked by creative and political experimentation and which was, notably, the decade of Murray’s first fully mature work. In the new market boom, large Neo-Expressionist and appropriational painting, largely by male artists, was the dominant medium and of course the favored market commodity, with women gravitating (and being pushed, by both external and internal forces) towards photography and photobased media (with correspondingly lesser market value). While the language of the heroic history of painting could still be applied to the former, along with newer modes of criticism influenced by postmodern theory, or, even, one might say, despite the dominance of the anti-essentialism of such theory, the other–work by women artists including those peripherally or explicitly interested in gender–was drawn to and delimited by the same theory with an emphasis on an anti-essentialism that particularly targeted painting.

A so-to-speak mantraic recap of that period might be, Lacan, Foucault, Derrida, Lacan, Foucault Derrida, and, when it came to women artists, Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, Jenny Holzer, Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, Jenny Holzer…not forgetting Baudrillard and Mary Kelly, and more, but you get the idea.

Of course there were powerful women painters during that time period, including in addition to Murray, artists such as Susan Rothenberg and Ida Applebroog. But international exhibitions and biennials of contemporary art usually included very few women and of these the three mentioned above were ubiquitous.

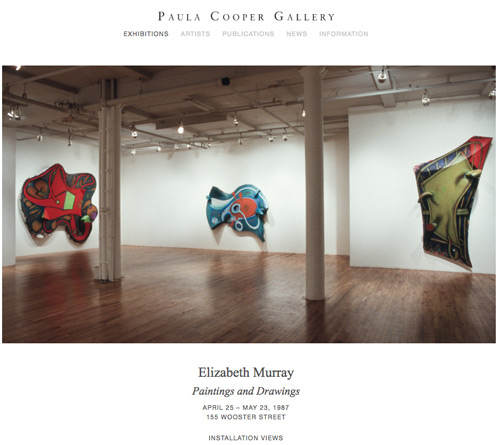

And at that time, as I have observed elsewhere, it was useful for such painters to do work that could be parsed for their representational depiction of ideas about the female body, femininity, gender and feminism. Abstract artists–including women painters and sculptors whose work had been so influential and notable within feminist art discourse in the 70s–often felt left out of major exhibitions and texts devoted to women artists and feminism. In that moment Elizabeth Murray’s work was a beacon. To walk into Paula Cooper Gallery in the 80s or into Murray’s first major museum retrospective, at the Whitney, in April 1988, was a thrill and inspiration. To walk into Pace Gallery today is to experience that thrill anew.

Elizabeth Murray, “Making It Up,” 1986. Oil on canvas, 10′ 4 1/8″x7′ 11 1/8″ Image used by permission © The Murray-Holman Family Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The paintings from that period, now as when they were first created and exhibited, are bold, confident, powerful, intensely physical, courageous in their assertion of space on and off the wall, massive, inspiring in their use of color and paint texture and application.

But at some level the paintings operated and still operate beyond discursiveness. At a time when representation and enculturation of female identity was the issue at hand, feminist criticism couldn’t quite get a grip on a large twisted broken shield or heart like a shield working at a monumental scale, leaping out at you from the gallery wall, where you couldn’t directly address a feminist narrative by which I mean the narrow interpretation of what a feminist narrative might be where representation, figuration, and appropriation would allow you to speak of psychoanalysis, for example. Not that Murray wasn’t widely admired but the important feminist criticism of the day was focused on artists whose work could be discussed in relation to Freud, Lacan, Foucault, Derrida, Kristeva, and there were clear specifications of what work was part of that discourse and which wasn’t.

These theoretical references were also the lodestars of a dominant anti-essentialist discourse on how the female and the feminine were socially constructed and you couldn’t address Murray’s work without dealing with how engaged she was with the basic components of painting—figure and ground, oil on canvas and support, and this was in the dangerous territory of the essentialism of painting itself. And while in fact Murray’s work demolished Greenbergian tenets, at the same time her painterly ambition both embraced and reinvigorated the great tradition of New York School painting of which his philosophy were an important component.

Elizabeth Murray, “Like A Leaf,” 1983. Oil on canvas (6 parts) 98″x90″x9″ Image used by permission © The Murray-Holman Family Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

And, finally, as I try to give a sense of what being an artist in the1980s was like, Murray did not use “the language,” as someone once used the term to me, “those of us who have the language.” Her references could be literary and philosophical, what she said about her work was deep but different than an academic discourse, as much rooted in daily visual experience as in popular culture and in direct transmutation into paint of such experience. In discussing her work she did not use what later became known at International Art English. Very much like Philip Guston, she was very eloquent about becoming an artist, the personal and cultural sources for her imagery and style, and about studio process.

I have a history of constructing vivid but sometimes revealed to be false memories of favorite paintings by artists I love: a painting will be a lodestar in my mind, and I will remember not just it, but the wall of the museum or gallery that it hung on, and perhaps at the core of my memory is my memory of myself at the instant of seeing it. It is the moment of the coup de foudre, love at first sight, but, more than that, of when an imperative and a challenge is revealed to you in one glance. As time passes, I try to find the work again, but often can’t find any trace. Sometimes it is eventually proven to me that it never existed as I had remembered. For example, for the longest time there was a Guston painting of cherries that I had seen at McKee Gallery. There are many wonderful paintings of cherries by Philip Guston and though I love them all, somehow that one painting was in my mind the best one. I remembered where it was installed the gallery, on the back side of the back dividing wall. But no reproduction matched my memory. Finally I asked about it at David McKee Gallery, Guston’s dealer for four decades, and they figured out the year of the show I was talking about and were able to show me the layout of the show and the images, and evidently I had constructed the painting. Strangely, once my memory was proven to be false, the image began to fade in favor of verifiable works, though the ideal persisted.

Another such painting that stood out in my memory in my personal archive of works particularly significant to me–was a large multi-part question mark I had seen at Murray’s retrospective Elizabeth Murray, Paintings and Drawings, which opened at the Whitney in 1988. I never forgot the work, or more specifically, its subject, its materiality, its scale. And, again, more specifically, I remembered myself seeing it, being struck by it: it was there and I saw it, in that way you remember seeing across the street or across a large room a person who you will later meet and fall in love with, but you already did at the first instant of vision. Over the years I always wanted to see it again, and I looked for images of that painting, without success. After the Guston cherries episode I understood that I was capable of inventing archetypal paintings by other artists. Had I made up Elizabeth Murray’s monumental question mark?

Lurking in the back of my mind when I went to see the current show at Pace Gallery was the hope that it would be there. Without seeing it I walked purposefully towards finding it. And, in the back wall of the back room, there was the painting, Cracked Question. Apart from being more askew than I remembered, less vertical, more horizontal, it looked like the painting I fell in love with but doubt set in when examination of the Whitney exhibition catalogue did not include it. Detective work and pestering of friends ensued and mention of the painting was found in a review of the show written by Rob Storr,

Like an interrogative sentence in Spanish, Murray’s show both began and ended with the same punctuation mark, but one whose significance vastly exceeded its simple editorial or grammatical function. Looming just beyond the brightly hued paintings of the 1970s that created one at the entrance, Cracked Question (1987), a mammoth multi panel, multi-faceted picture that dominated the central room of the Whitney installation, was at once the first image on which one’s eye’s fell and a tense conclusion to the chronological sequence of intervening works. (Storr, “Shape Shifter,” Art in America (April 1989), p. 275)

Storr’s description of the pivotal position of the work in the show filled in my memory of seeing myself seeing it. [Because such stories interest me, I think the solution of the mystery is that the show originated in 1987 in Dallas at the Dallas Museum of Art, and was surely planned before that. Cracked Question dates from 1987 and the Whitney show opened in the spring of 1988 so it must have been a late, but, as Storr indicates, central addition.

Elizabeth Murray, “Cracked Question,” 1987. Oil on canvas (6 parts), 13′ 5 1/2″x16′ 2″x23 1/2″ Image used by permission © The Murray-Holman Family Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The work is massive, sober, architectural, dramatic. In my notes I wrote that it is dispositive, it feel instinctively that it solves a problem, a conflict, although its subject stays at the moment of the question. It is sculptural and would be seen as such under any circumstances, but the dark grey and metallic silver paint emphasizes the segmented painting’s relation to steel and stone. Each part is as powerful as the whole, yet the whole embodies its existence as language–speaking of Murray’s relation to “the language,” Cracked Question is language. It doesn’t represent a punctuation mark, it is a punctuation mark. It does not only pose but it is a philosophical question and a philosophical text, that takes place in the languages of form and color and space and matter.

A friend spoke to me of the “ferocity” of Murray’s work. Cracked Question embodies and exemplifies that ferocity.

This show arrives at a moment when, after several years of the dominance of abstraction–much of it a variant of what has been termed “zombie formalism”—that is, constructions and deconstructions of established tropes of abstraction, usually very elegant, and often disconcerting, particularly for those viewers who lived through the “original” phases being sampled or replicated, because of the works’ lack of the historical content and the crucial trace of struggle for form and content that had characterized those earlier movements–there are suddenly dozens of exhibitions of figurative painting ranging in style from Alice Neel-like realism to a poetic fantastic that emerges from surrealism and can sometimes border on millennial pathos. So, right now, figuration is in, not in all cases with a overt political message, unless in terms of the racial or gender identity of the artist and the figures represented in the paintings.

So is this a case of bad timing or of good timing for this presentation of Murray’s great works from the 1980s? It is always fascinating to think about how sometimes museum retrospectives, though planned years in advance, open just at the moment when that artist’s work or that artist’s most controversial works look presciently fresh to a new generation. Often such works are revived precisely to give contemporary artists the historical buttress that will burnish their reputations: thus late figurative works by Picabia, previously seen as kitschy aberrations were first restored to critical favor in the 1980s at a time when it seemed to retrospectively offer an important patrilineage for and contribute to the historical buttressing of the work of a then emerging David Salle. Last year’s extensive Alice Neel exhibition at David Zwirner seemed perfectly keyed to the work of emerging art stars like Jordan Casteel. So what will young artists experiencing this moment’s stylistic Zeitgeist make of Elizabeth Murray’s greatest works, seen at this moment?

Elizabeth Murray, Interview with Sue Graze and Kathy Halbreich, “Elizabeth Murray, Paintings and Drawings,” exhibition catalogue, H. N. Abrams, 1987, p.131.

It should be noted that while the overall effect of Murray’s work is one of abstraction, and the artist described herself as an abstract painter in an interview included in the 1987 catalogue, there are many representational elements and references in her paintings, in a stylized style emerging from cartoons, comics, and graffiti as well as from pop artists like Claes Oldenburg: works are shaped like shoes or cups and contains stylized abstracted but identifiable figuration and still-life imagery. But her relation to representation is not in the realm of narrative or allegory, the thing itself is the important thing, the painting as an object that projects into our space carrying pigment on its surface. The importance of three-dimensionality is apparent when one compares her oil paintings from this period to related drawings: even when these are on several pieces of paper creating a shape or a broken field, they operate in a more conventional relation to form. The objectness of the shaped paintings from this period makes them always more than the working out of abstracted, biomorphic or geometric forms on a flat surface, since the form of the support itself is a biomorphic or geometric abstraction.

Elizabeth Murray, “Table Turning,” 1982-82. oil on canvas (2 parts) 8′ 10 1/4″x8′ 2 1/4″x4 2/4″ Image used by permission © The Murray-Holman Family Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

That places them in yet another situation of appearing to be beyond language: how she declares space is different than Barnett Newman’s declaration of the equivalence between figure and ground: what is painted as form and shapes on the large shaped works may be securely within the realm of figure, but on the other hand the whole object itself is figure on the ground of the wall in a way that conventional easel paintings, even Murray’s own earlier works, are not. Thus, again, if the works can’t be incorporated or tamed into discourse of gender representation, nor to the terms of the new critical language of gender, racial identity, national identity politics, they also can’t be reduced to the purely formal terms of the earlier discourse that had characterized painting from the late 1940s to the 1970s.

The sculptural nature of the works emphasizes the sculptural nature of oil paint itself. One of the things I have always found the most inspiring about these works is how the three dimensional support allows me to really experience the physicality of pigment. This is one of the things that painters live for, the moments when paint comes alive in a generative fashion, so for me, how Murray allowed oil paint to dry unevenly–an area of color will be matte and then shiny, which in itself becomes sculptural. And it is never enough to look them frontally, you have to experience the surface from the side to really see the color and the brushstrokes.

A year after Murray’s show at the Whitney, which included, in addition to Cracked Question, a number of the works in the current exhibition at Pace, I wrote the essay “Figure/Ground,” in which I confronted the critique of painting I have indicated as dominant in the 1980s with other discourses that were not usually brought to bear on it, including those of feminism and of feminist studies of the gendered, misogynist aspects and roots of fascism. In one of the last paragraphs of the essay, I wrote about some of what I love about painting:

For a painter there is certainly tremendous pleasure in working out a thought in paint. I tis a complete process in terms of brain function: an intellectual activity joining memory, verbal knowledge, and retinal information, is a given visible existence through a physical act. But the value of painting cannot rest of any individual artist’s private pleasure. Painting is a communicative process in which information flows through the eye from one brain, one consciousness, to another, as telemetric data speeds from satellite to computer, without slowing for verbal communication. Incident of paint linger in the working mind of the painter as continuous thrills, as possibilities, like words you may soon use in a sentence, and–in a manner that seems to exist outside of spoken language—as beacons of hope to any human being for whom visuality is the site of questions and answers about existence. The black outline of a rock in a Marsden Hartley landscape, the scumbled white shawl in a portrait by Goya, the glaze of a donor’s veil in the Portinari Altarpiece, the translucent eyelid of Leonardo’s Ginevra di Benci, the pulsing red underpainting of a slave’s toe in a Delacroix, the shift from shiny to matte in a passage of indigo blue by Elizabeth Murray, are only a few of a storehouse of details that are of more than professional interest to me.

Images used by permission © The Murray-Holman Family Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York