There is a certain kind of news story that gets introduced by friends on Facebook as “Not The Onion.” This is a discussion prompted by one such headline.

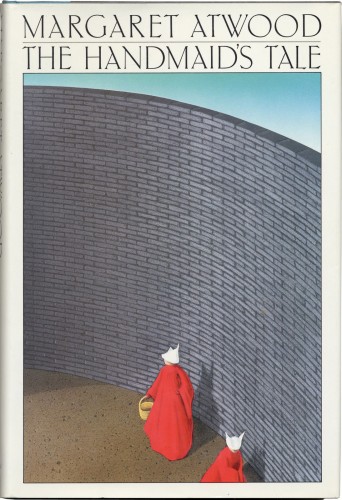

Let me try to contextualize the recent announcement that the Sackler Center will give its 2015 Sackler Center First Award to Miss Piggy. The ceremony is June 3rd.

“Moi!” exclaimed Miss Piggy!

“Mais quelle cochonnerie!” exclaimed Madame de Beauvoir

It could be a new Fable de La Fontaine: since Simone de Beauvoir’s nickname was Castor, the beaver, because of her lifelong habit of intense scholarly studiousness and hard work (“it was while studying for the agrégation that she met École Normale students Jean-Paul Sartre, Paul Nizan, and René Maheu (who gave her the lasting nickname “Castor”, or beaver. The jury for the agrégation narrowly awarded Sartre first place instead of de Beauvoir, who placed second and, at age 21, was the youngest person ever to pass the exam”), perhaps Cochon et Castor would be a good title for the fable. I won’t attempt verse:

Cochon, Miss Piggy, having been a television and movie puppet character, whose main characteristic is that she is self-absorbed and boy crazy and is always trying to get Kermit (a male frog) to marry her, one day encountered Castor, the eager brilliant philosophical and feminist beaver Simone de Beauvoir (who, it must be said, was crazy about Jean Paul Sartre who looked a bit like a frog). “I’m getting the 2015 First Feminist Award from the Sackler Center at the Brooklyn Museum on June 3. Gloria Steinem is presenting it to Moi, Miss Piggy!” “Vous vous foutez de moi,” exclaimed Castor.

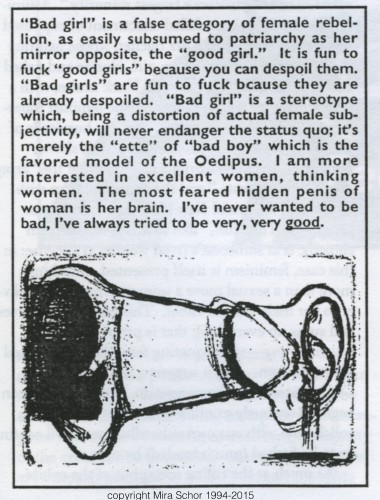

Fables always have a moral. What is the moral of this fable? That second wave feminists have no sense of humor? This is a long-standing convenient calumny against women who actually care about human rights, based on the fear that what women’s humor might include is mockery of men. FYI: Just in the last month, these mordant videos were circulating on social media (+some research of my own going a bit further back in time): Tina Fey, Amy Schumer (with Tina Fey, Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Rosanna Arquette), Amy Schumer, and Lily Tomlin, for good measure (a contemporary of Miss Piggy).

What was the Sackler Center’s awards selection committee thinking in making this selection? What would a feminist fly on the wall have heard as they came up with this idea?

Nothing against Miss Piggy, though in terms of her award from the point of view of her validity as a feminist icon, taking this perfectly seriously, take note that she has most often been performed by Muppet puppeteer Frank Oz as well as a few other male puppeteers over the years (and one woman on TV). There were two women significantly involved in her creation and her public image, principally Muppet designer Bonnie Erickson who created the character and based her name on her mother’s love of singer Peggy Lee and Calista Hendrickson was Miss Piggy’s costume designer and stylist. Neither woman is mentioned on Miss Piggy’s Wikipedia page, and her Official Muppet website bio is an in-character fictional performance. The fact remains that her character may have been physically shaped and originally imagined by a woman, but she is scripted and voiced by a man’s imaginary, not a woman’s.

Since calling a woman a pig is a familiar way of saying she’s a slut, can one interpret Miss Piggy’s name and persona as a feminist recuperation of a sexist slur in order to make it a mark of pride, the way the word “cunt” was revalued by early feminist pioneers like Judy Chicago and her students in the Fresno Feminist Art Program in 1970?

Miss Piggy is big, brassy, and loud, a relentless self-promoter. She is not embarrassed by her desire and she’s not shy about beating Kermit or anyone else upside their head if they get in her way. It’s a kind of do-me feminism, pig puppet style. So it could be argued that she displays feminist or certainly feminist-inspired traits. But she is also a kind of porcine Lucy Ricardo, always claiming talent she doesn’t have, with Kermit as a more patient and laid-back version of Ricky Ricardo. Given the historical situation of her birth in the mid-1970s, she is all at once a throwback to 1950s genteel oppression via The Feminine Mystique, an emanation of the Women’s Liberation movement of the 1970s, a sign for the 1980s backlash against feminism with its curiously confusing characteristics of ambition and entitlement, and since she performs femininity rather like a drag queen, in terms of the way she often dresses, she is an interesting model for gender play today. She is also involved in a trans-species romance, I will say no more!

Previous winners of this award have included Marin Alsop (conductor and violinist, director of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra), Connie Chung (journalist and glass ceiling breaking TV anchor), Johnnetta B. Cole (African American anthropologist, educator, college president, and director of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African Art), Wilhelmina Cole Holladay (founder of the National Museum of Women in the Arts), Sandy Lerner, Lucy R. Lippard, Chief Wilma Mankiller (posthumous, first female chief of the Cherokee Nation), Toni Morrison, Linda Nochlin, Jessye Norman, Associate Justice Sandra Day O’Connor (Ret.), Judith Rodin (President of the Rockefeller Foundation), Muriel Siebert (financier), Susan Stroman, and Faye Wattleton (the initial awardees in 2012), Julie Taymor (2013), Anita Hill (2014)–all women whose names can be accompanied by the epithet “ground-breaking” and who mostly do not need a Wikipedia bio link, and, again, Miss Piggy, in 2015, who also doesn’t need a Wikipedia bio, though “ground breaking” is not so clear: “The 2015 Sackler Center First Awards honors performer, actor, writer, and icon Miss Piggy, for more than forty years of blazing feminist trails with determination and humor, and for her groundbreaking role inspiring generations the world over.” “The evening features Miss Piggy in conversation with Gloria Steinem.”

Here a thought occurs to me, a historical conjecture, namely how willing Eleanor Roosevelt was to embrace and use the platforms of whatever she could from and within popular culture of her day if it could help a cause she deeply believed in or where she thought her name would add weight to a cause or benefit the people.

Have I just talked myself or anyone else into thinking that Miss Piggy is a sensible choice for the Sackler Center’s First Award or do I still feel that this choice is emblematic of a certain devaluation of feminism or at the very least of a certain desperation in the face of popular culture? It definitely is desirable or, these days, imperative even to get mass media attention and it’s important to be fun and appealing, or, in the parlance of the day, to be “relateable.”. Like many things that happen, one is supposed to take it in good humor and take a positive point of view on everything. It is sometimes hard to remember what something really is or means, like feminism.

But why this choice now? The Muppets, now a Disney product, are returning to television in the fall, on the Disney Network, so the choice suggests some corporate synergy on both sides here: Miss Piggy gets a distinguished award for feminist pioneers and I hope the Sackler gets a generous donation. Mystery solved?

The background for my receiving the notice of the Miss Piggy Award are the numerous stories and publications pertaining to women in the arts and to feminism which have circulated in the media in hard print and online the past few weeks. On the statistical front, Maura Reilly’s “Taking the Measure of Sexism: Facts, Figures, and Fixes”, a comprehensive and dispiriting update of statistics on the status of women artists in the artworld, previously researched and exposed in recent years by The Guerrilla Girls, the Brainstormers, and Micol Hebron’s project Gallery Tally, is being widely shared on social media, along with all the other statements by major women artists and art historians featured in the June 2015 issue of ARTnews.

Meanwhile the May 15 Sunday New York Times published two, apparently uncoordinated, articles pertaining to women, particularly older women, whose simultaneity nevertheless held a chilling message for women. In T, the Times‘ glossy Fashion and Design magazine, one found author Phoebe Hoban‘s thoughtful article “Works in Progress,” about “A very small sampling of the female artists now in their 70s, 80s and 90s we should have known about decades ago.” These included Agnes Denes, Carmen Herrera, Joan Semmel, Lorraine O’Grady, Rosalyn Drexler, Dorothea Rockburne, Etel Adnan, Michelle Stuart, Faith Ringgold, Judith Bernstein, and Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian [nota bene, the long struggle to get some long deserved success was exemplified by the final ironic injustice that only 4 of the 11 women profiled in the article made it into the print version + 2 who had their pictures reproduced in the Editor’s note for the whole issue, the rest were online only, though I suppose these days that counts for more]. The article pointed to a phenomenon that has long been a source of internal gallows humor among women artists, that if you don’t make it big by age 30, (and if you’re not, as one friend of mine says, the one crazy woman the artworld allows in every decade), you have one more chance, maybe, if you live to be 80, or now 90 or even 100 to get some attention [because 90 is the new 70]. In fact the Times piece was followed by so many articles about older artists, female and also male, that it’s been hard to keep up with them, including in today’s Times, “An Artist’s Thoughts of Retirement, Quieted by the Constant Churn of Creativity,” about the painter Audrey Flack, who just celebrated her 84th birthday this weekend, and among several other examples, including in W Linda Yablonsky’s “Young at Art,” and on the Huffington Post, “15 Badass Art World Heroines Over Seventy Years Old”.These articles left out several prominent older women with recent or current notable exhibitions, including Joan Snyder, Joyce Kozloff, and Ida Applebroog, to name but a few. If any such artists feel left out of this “moment,” dubious a pleasure though it may be to be recognized as a neglected senior citizen but, nevertheless, at least that, maybe they should take heart that they are just too young to be included!

One has to wonder what is driving this sudden interest in older women artists: might it be the case that, aside from the general rules of market and fashion that create a herd-mentality trend once it starts, older artists are seen to and perhaps do indeed carry markers of authenticity, depth, and experience that are felt to be lacking in contemporary post-internet culture despite the more conventional point of view that only millennials and post-millennials can understand the contemporary moment. Is the current interest in old artists a fad or a genuine tropism of culture, a revenge of artists against “creatives”?

As one of the women included in one of the articles recently said to a friend, “too little, too late.” Artist Chana Horwitz worked in obscurity for decades, finally beginning to achieve some success in her last years. She received a Guggenheim award in 2013 shortly (like days) before her death at age 81. A retrospective exhibition of her work opened in Berlin this winter. And on artnet yesterday: “Carmen Herrera, Who Sold Her First Painting Aged 89, Turns 100 Years Old.” Herrera is being given an exhibition at the Whitney Museum in Fall 2016, when the artist will be 101 or even 102. Frank Stella’s major career retrospective will open at the Whitney in October 2015. Patience is indeed a feminine virtue.

To enjoy that late attention you don’t just have to have lived that long, but you have to have been able to keep your body, your mind, and the work you have done in your long lifetime in good enough shape to be there if and when the bottle finally stops spinning in front of you.

But it well may be that even if you live so long, when the late success comes, you may no longer be able to use it to leverage the production of more work–Louise Bourgeois is a rare example of a woman artist who was able to still have enough time left to really use her relatively late success (with a revival of interest gathering momentum in her 70s) for a twenty-five-year run of creativity at the grander scale that her late financial success afforded her, but apart from all other circumstances the fact is she happened to have had the good fortune to live to a great old age in a home she owned, filled with her work.

A more haunting note is struck in Lynn Hershman Leeson’s 2010 film !Woman Art Revolution when Nancy Spero, widowed and having suffered crippling chronic illness since mid-life and near fatal health crises in her later years, says: “All these hurdles to come up against, to try to jump up against. Now I’ve had a really long career. I can’t believe it but this last year in my career was the best I’ve ever had. Now just imagine if I hadn’t lived to see this, at the age of 81 and it’s like a torrent of wonderful things that happened last year, the recognition I’ve had, what that means in terms of acknowledgement.” She says it totally sincerely but given her character and experience also with full knowledge of the irony and raging unfairness of such a narrative. (link to Spero’s footage here, statement quoted here begins at about 5 minutes in). The interview was filmed in February 2008, Spero died in October 2009.

As an apparently unconscious dog whistle of how daunting it is to meet these conditions, the same day as the T feature on older women artists, the Sunday Times Magazine‘s cover article was “The Last Day of Her Life,” about gender studies pioneer Sandra Bem‘s decision to plan her own suicide, upon receiving a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Even to accomplish that heroically depressing task, like the women artists who have had to keep things together until their ’80s and ’90s, she had to be able to do it when she was still able to do it herself so that no one else would be held legally responsible for her death, while requiring the financial wherewithal and the loving support of her family to accomplish her goal.

Keep in mind that all studies point to the exceptional economic fragility of older women, according to numerous studies including this from the Institute for Women’s Policy Research: “Around the world, women tend to be in poverty at greater rates than men. The United Nations reported in 1997 that 70 percent of 1.3 billion people in poverty worldwide are women, while American Community Survey data from 2013 tells us that 55.6 percent of the 45.3 million people living in poverty in the United States are women and girls. Women’s higher likelihood of living in poverty exists within every major racial and ethnic group within the U.S.”

But, hey, girls, you just have to “lean in.” That is the message propounded by most of the 62 women features on artnet in their “62 Women Share their secrets to artworld success”–part 1 and part 2. As one of my friends pointed out, secret #1 seems to be, don’t be an artist, since all the women are dealers, museum directors and power brokers of one kind or another.

The secret of success for women artists is evidently, live a really long life and don’t get Alzheimer’s. Miss Piggy is very fortunate that she is not prey to the entropy of the flesh, since as Tina Fey would put it, she is not a “human woman,” she is a puppet who can be replicated when necessary. By the way, today a Google search for images of pigs yields this headline and video, “Mini pot-bellied pigs love on Alzheimer’s patients”, about the use of therapy pigs for Alzheimer’s patients.

Meanwhile, as I pointed out in a post on Facebook last week,

Everyone is sharing the online material from the June issue of ARTnews devoted to women artists and feminism as well as many other links relating to struggles for women in the arts and to successful women in the arts — I have a browser window open to “62 Women Share Their Secrets to Art World Success: Part Two” on artnet. But here is one bottom line for me: complete nonentities and creeps like George Pataki — George Pataki for Christ sake, the absolute definition of nonentity–and Chris Christie get up in the morning, decide they’re going to run for President and people are going to throw *millions* of dollars in their direction even though everyone involved knows they don’t have a chance in hell of even being serious contenders much less winning. That’s literally what I think of every morning as I struggle to figure out how I will negotiate the challenges of every day: “and Chris Christie is running for President and getting money for it”

There is a pig link here and it isn’t just that Christie actually looks like a pig–sorry to malign pigs who can be very cute and who are genetically quite close to humans—but earlier this political season Governor Christie “vetoed a politically charged bill that would have banned the use of certain pig cages in his state, a move many observers see as aimed at appeasing Iowa voters ahead of a potential 2016 presidential run.” I’d like to think that Miss Piggy would take umbrage and would understand my frustration at the confidence Christie has in himself which is based on so little, compared to the doubts and struggles that so many talented women endure despite so much. It would be great if Miss Piggy could add a little bit of political relevance to the new Muppet show with a skit about Christie’s pig policy. Bring some politics in there to live up to your Sackler First Award.

So, to recap: Cochon et Castor? Feminists have no sense of humor? Corporate synergy? Wait until you are 90 years old? Fine. For next year’s Sackler Center First Award let me take the liberty of nominating some worthy funny feminists: give the award to Tina Fey, Amy Poehler, Amy Schumer, and give it up for Kristen Schaal!