The first issue of M/E/A/N/I/N/G: A Journal of Contemporary Art Issues, was published in December 1986. M/E/A/N/I/N/G is a collaboration between two artists, Susan Bee and Mira Schor, both painters with expanded interests in writing and politics, and an extended community of artists, art critics, historians, theorists, and poets, whom we sought to engage in discourse and to give a voice to.

For our 30th anniversary and final issue, we have asked some long-time contributors and some new friends to create images and write about where they place meaning today. As ever, we have encouraged artists and writers to feel free to speak to the concerns that have the most meaning to them right now.

Every other day from December 5 until we are done, a grouping of contributions will appear on A Year of Positive Thinking. We invite you to live through this time with all of us in a spirit of impromptu improvisation and passionate care for our futures.

Susan Bee and Mira Schor

*

Susanna Heller: A Pussy in the Boardroom

Susanna Heller, ACTUAL SIZE (A Pussy in the Boardroom), December 2, 2016. Oil, fabric, mixed media on wood, canvas and board, 32 x 28 inches spherical, detail.

In the sphere pictured above you see visceral images: paint marks, line marks, blobs, scumbles, drips, and shapes evoking pussy’s world. The escalation, diminishment, or distortion of pussy’s scale, shape,and actual appearance occurs in every person, but the most powerfully destructive distortions are those coming from that great circle of violent power: the men at the table!

Where is MEANING now? One of many places to find meaning is in the glorious force of the physical weight of marks on surface, something I have always nicknamed ‘groiny-ness’. Whether making things or experiencing things, groiny-ness is empowering and brings courage and joy.

More and more I realize that simply insisting on this feeling in one’s life and work is pretty frightening and challenging to the boardroom-table-men.

Susanna Heller was born in New York. When she was 7, her family moved to Montreal, Canada. After completing college at Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in Halifax, Heller returned to New York in 1978. She has lived and worked in Brooklyn since 1981. Her awards include grants and fellowships from the NEA, Guggenheim Foundation, Joan Mitchell Foundation, The Canada Council, and Yaddo. She is represented by the Olga Korper Gallery in Toronto, John Davis Gallery in Hudson, NY, and at MagnanMetz gallery in New York.

*

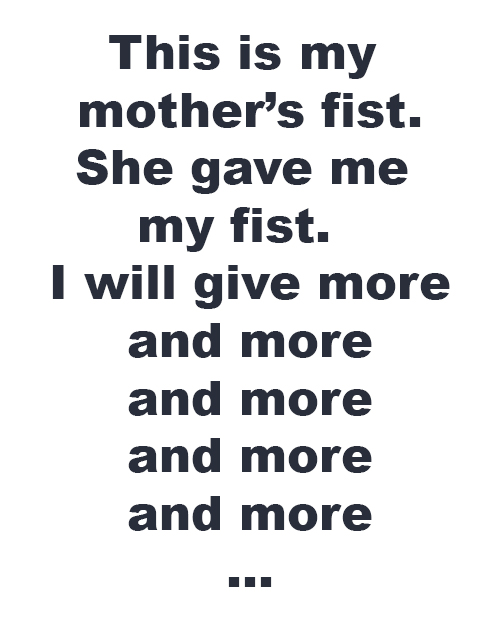

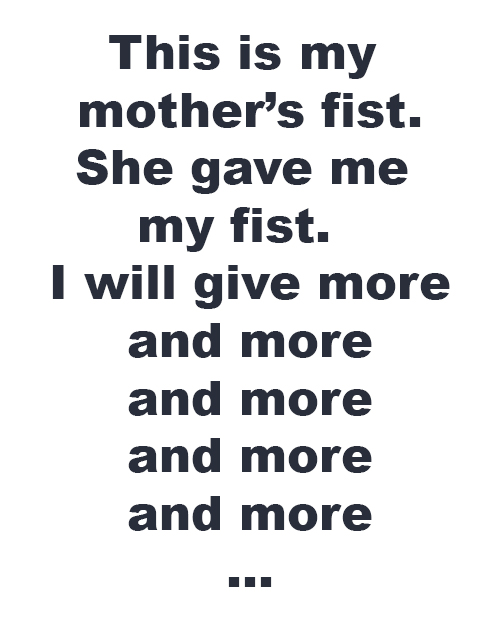

Rachel Owens

Rachel Owens, Ginny’s Fist, broken glass and resin, 2015.

Rachel Owens lives and works in Brooklyn. Her first job in NYC was helping Mira Schor where she first read M/E/A/N/I/N/G. She makes sculptures, performances, and videos, teaches at SUNY Purchase College, and works with people in all parts of the world. La Lutte Continue!

*

Mary D. Garrard: Three Letters

Dear Enlightened Men,

Thank you for supporting Hillary, even though you never really got it. Nor could you have, unless you’d lived it viscerally, and your support of her is a credit to your moral imagination. But you never understood that to see her candidacy through the narrow prisms of her emails and her flaws (as if our greatest heroes didn’t have any flaws) was to distort reality and deflect the energy. Many of you are saying that this election was really about race, and Obama. Pent-up resentment was part of the story, but this time it was her name on the ballot, and her face in the crosshairs. You kept on saying that she just didn’t inspire us. What do you mean us, kemo sabe? Electing Hillary Clinton president was never some kind of tokenist box-checking, it was the end point of a long historical arc that, we now know, may not necessarily bend toward justice. It was to have been, as one writer (male) put it, the fulfillment of Seneca Falls.

Dear Clueless Women,

You say that to vote for her because she is a woman would be sexist. No, it wouldn’t. It would be a recognition that the little extra that is always required of women was especially needed now. To fixate on her rare flashes of self-interest or, for god’s sake, her ambition, in the face of the spectacular evidence in this election of patriarchy’s ever-present leer – pathetic or menacing, depending on its power status – is to be blissfully unaware that the butcher’s fat thumb is always on the scale. Until now, when the opportunity to embody and symbolize women’s fully equal humanity was so close at hand. Hillary herself has called out eloquently to little girls, as the standard-bearer of the most recent generation to put up a political fight for what was once called women’s liberation. It’s a liberation that has yet to fully take root in our psyches, but will eternally bloom in the hearts of little girls.

Dear Hillary Rodham Clinton,

As a participant, like you, in that now historical women’s movement, I want to thank you on behalf of our generation. Thank you for accepting and taking forward the torch that, in the reach of historical memory, was first ignited in the fifteenth century by Christine de Pizan, and carried proudly by Laura Cereta, Lucrezia Marinella, Mary Wollstonecraft, Sojourner Truth, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Alice Paul, Eleanor Roosevelt, Eleanor Holmes Norton, Gloria Steinem, Shirley Chisholm, and so many others. Sure, it’s comforting to hear you say that a woman will be president one day, maybe sooner than we now think. But it’s cold comfort to realize that once again, a woman has paid a steep price for challenging the patriarchy, and once again the women’s agenda has been subordinated to supposedly more pressing concerns. This long struggle for equality has seen both victories and defeats, and I am so sorry you had to be the sacrificial lamb this time. But you have brought fresh energy and inspiration to the cause, and you’ve given us another role model for the dream that will never die. Thank you, Hillary, for showing a new generation of women and girls what feminism is. We are all so very proud of you.

Mary D. Garrard, Professor Emerita at American University, is the author of Artemisia Gentileschi (1989), and many other writings on women artists and gender issues in art history, including Brunelleschi’s Egg: Nature, Art and Gender in Renaissance Italy (2010). With Norma Broude, she co-edited and contributed to four volumes on feminism and art history, including The Power of Feminist Art (1994). Broude and Garrard were activists in the Feminist Art Movement of the 1970s and ‘80s; Garrard was the second president of Women’s Caucus for Art.

*

Kate Gilmore

“It was the Future- Hillary and Mom,” 1996.

Kate Gilmore lives in NY. She has participated in the 2010 Whitney Biennial, The Moscow Biennial (2011), PS1/MoMA Greater New York, (2005 and 2010), in addition to numerous solo exhibitions. Gilmore is Associate Professor of Art and Design at Purchase College, SUNY, Purchase, NY.

*

Maureen Connor

For my contribution I’ve used quotes from M/E/A/N/I/N/G Online #4’s Feminist Forum, 2007, as responses to the 2016 election. All of the essays from that issue were moving and inspiring; I’ve chosen these excerpts because for me they can serve as reminders and guides over the next four years.

Sheila Pepe, writing about her mother: As a Sunday painter and homemaker, visibility was not an issue for Josephine. Not like it is for her daughter and her artist colleagues. Service was Josephine’s guiding principle, and as much as I once completely rejected this call as decidedly anti-feminist, I now know its great value. Directing one’s work in the service of a greater good is at the heart of social justice, and therefore, Feminism. And that the art world, no matter how progressive it perceives itself to be, no matter how well the objects it produces claim the ground of good politics, the mechanism of it will always benefit from some old fashioned feminist practice: women willing to work toward a more complex and equitable future.

Carolee Schneemann: (Notes from 1974 for Women in the Year 2000 by CS) In the year 2000, books and courses will only be called, “Man and His Image,” “Man and His Symbols,” “Art History of Man,” to probe the source of disease and mania which compelled patriarchal man to attribute to himself an his masculine forbears every invention and artifact by which civilization was formed for over four millennia.

Faith Wilding: I am NOT interested in canonization or star-making or genius pronouncements. Rather I’m calling for a kind of deep socio-cultural history that can be helpful to all generations of feminists, students, artists, in understanding specifically how feminist artists have used the philosophy, politics, and practices of feminism to embody new images, visions, inventions, ideas, processes, and ways of doing things differently. Dissing “cunt art” was like shooting fish in a barrel for art critics, but let’s see them engage in specific discussions of how feminism can be (and is) embodied as an aesthetic, and as a LIVED ethics of justice.

Mira Schor, speaking about giving tours at the feminist installation, Womanhouse in 1972: One day when I was there, a number of middle-aged ladies from the neighborhood came by in their housedresses. As our little group of young feminist art students realized that we were approaching Judy Chicago’s Menstruation Bathroom, filled with feminine hygiene products and “bloody” tampons, we melted away, leaving these ladies to their own devices. Later, they came to find us and laughingly chided us for thinking they would be embarrassed. I realized how much we were still girls while they were women, and also how one should never underestimate any audience for art.

Maureen Connor, collage with photo of “Thinner Than You”, 1990 and images of Fasicat Sexy Whole Body Stockings Unisex Bondage Sheer Encasement Cocoons, 2016

Maureen Connor’s work combines installation, video, interior design, ethnography, human resources, feminism, and radical pedagogy. Current projects include Dis-con-tent, a series of community events that considers the human story behind certain medical advances; and her ongoing projects Personnel and with the collective Institute for Wishful Thinking (IWT), both of which aim to bring more democracy to the workplace. Now Emerita Professor of Art at Queens College, CUNY where she co-founded Social Practice Queens (SPQ) in 2010 in partnership with the Queens Museum, she also co-founded the Pedagogy Group, a cooperative of art educators from many institutions who consider how to embody anti-capitalist politics in the ways we teach and learn.

*

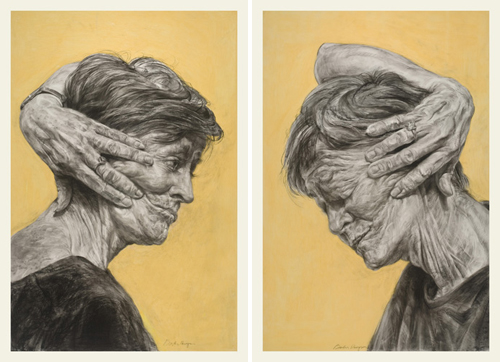

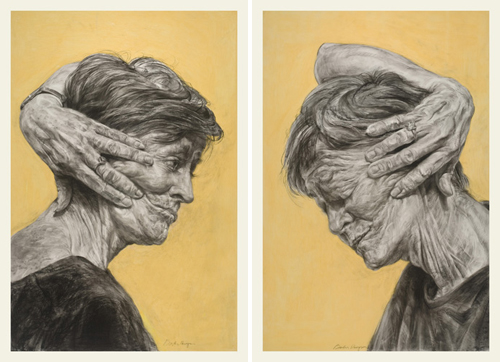

Bailey Doogan

Fingered Smiles

Bailey Doogan, Split-Fingered Smile and Four-Fingered Smile, 2013. Graphite on Duralar with Prismacolor on verso, 36” x 24”

These graphite self-portrait drawings, Split-Fingered Smile and Four-Fingered Smile, done in 2013 continue a series of works about manipulating my face to feign a pleasant, socially acceptable expression. I was invited to an opening that I couldn’t refuse, and so I stood in front of the bathroom mirror and used my own hand to push and pull smiles and grins onto my face. Thus a series of large charcoals, small paintings, and these graphite drawings ensued. This body of work from 2008 to 2013 alternately deepened, and ultimately purged, my depression. This July I started a series of paintings of women in long skirts.

Bailey Doogan, Skirt I and Skirt II, 2016. Gouache and oil on primed paper, 17” x 11”

Skirts

These small paintings on primed paper are the first two works in a series entitled Skirts. They were begun in July 2016. For years, my work has been about the body, usually women’s bodies, often specifically my own. I have always worked from photographs and for the past five years I’ve been unhappy with that process.

The first painting, Skirt I started as an earnest attempt to paint a portrait of my daughter’s Chihuahua, Kiko. After a few strokes quickly done, the women in the skirt appeared. My heart pounded. I kept on painting. I didn’t have a thought in my head. I was filled with joy. There are now six Skirts. Trump was elected. I cried for days but these paintings still fill me with joy, The skirts have a life of their own, girding and girdling my loins—Donald Trump can’t become my president, not mine.

Bailey Doogan is a seventy-five-year old artist living in Tucson, AZ and Nova Scotia, Canada. She is Professor Emerita at the U of A where she taught for thirty-two years. In 2009, she was awarded a Joan Mitchell Painting Grant.

*

Suzy Spence: Plotting

We’re so ready, so it’s a shock to learn that society is still not ready for us. There will be no basking in Hillary Clinton’s matriarchal glory. The difficult election proves that progressive politics were not as well seeded as we’d thought. To their credit Mira and Susan’s first issues of M/E/A/N/I/N/G read as if they were written today: gender and racial dissonance are the subject of most of the critical writing from the 80s and 90s and those concerns continue to be central. For sure leftist ideals once relegated to the university fringe have slowly infiltrated the mainstream, in part enabled by the massive transition we’ve made to live a portion of our lives online. It’s as if the digital age has allowed our collective consciousness to grow a subterranean stem, changing our perspectives in ways we could never have predicted.

That said, coming of age in the era of Obama was a stroke of luck for some of us. At eleven, my child is already meeting our immediate predicament with resistance. She is obsessed with the play Hamilton; its multiracial cast and tight poetic score are as poignant to her as the story being told. Nothing Lin Manuel Miranda intended to lay raw is lost on this child, she is for it, and of it.

I’ve also been struck by the work of two young journalists at The Guardian who produced a video series that’s run parallel to election news called The Vagina Dispatches. Mona Chalabi and Mae Ryan’s earnest, confessional reporting is hopeful, and reminds me that the fringe can always work the back end, in order to make the front end look deeply unstable. Their first episode asks the blunt question, “do you know about vaginas?” The reporters demonstrate anatomy using puppets, photography, quizzes — the material feminist artists have reached for time and again, but this go round is for the general public. They reveal there is a terrible lack of knowledge (almost as shocking as Hillary’s loss), but it’s remarkable to see a major newspaper supporting their earnest investigations, indeed putting them on the home page.

In the final episode Chalabi wears a soft costume vagina on a trip to Washington DC, her head popping out near the clitoris, the labia spreading around her sides. Somehow she manages to stroll nonchalantly about the Lincoln Memorial, stopping briefly in front of Lincoln’s spread legs. In doing so I felt she sent the message that being invisible doesn’t necessarily mean being without agency. In other words even if we’re hidden we can still be plotting. The problem of countering misogyny and racism will be ongoing, a giant project handed down from one generation to the next for as long as it takes.

Suzy Spence, Untitled, 2016. Paint on paper, 11”x14

Suzy Spence is an Artist and Curator who divides her time between Vermont and New York.

*

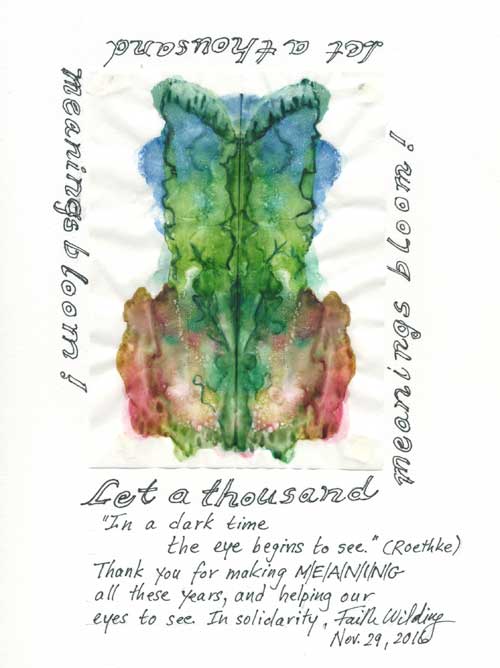

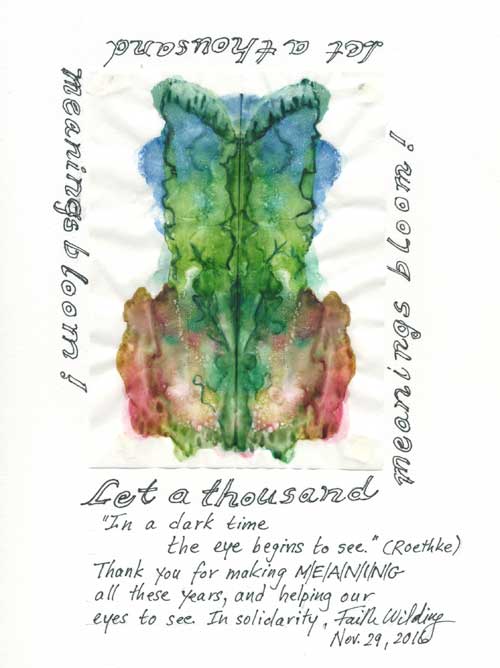

Faith Wilding

Faith Wilding is a multidisciplinary artist, writer, educator. Co-founder of the feminist art movement in Southern California. Solo and group shows for forty+ years in the United States, Canada, Europe, Mexico, and Southeast Asia. Her work addresses the recombinant and distributed bio-tech body in various media including 2-D, video, digital media, installations, and performances. Wilding co-founded, and collaborates with, subRosa, a reproducible cyberfeminist cell of cultural researchers using BioArt and tactical performance to explore and critique the intersections of information and biotechnologies in women’s bodies, lives, and work.

***

Further installments of M/E/A/N/I/N/G: The Final Issue on A Year of Positive Thinking will appear here every other day. Contributors will include Alexandria Smith, Altoon Sultan, Ann McCoy, Aziz+Cucher, Aviva Rahmani, Erica Hunt, Hermine Ford, Jennifer Bartlett, Jenny Perlin, Joy Garnett and Bill Jones, Joyce Kozloff, Judith Linhares, Julie Harrison, Kat Griefen, Legacy Russell, LigoranoReeese, Mary Garrard, Michelle Jaffé, Mimi Gross, Myrel Chernick, Noah Dillon, Noah Fischer, LigoranoReese, Robert C. Morgan, Robin Mitchell, Roger Denson, Tamara Gonzalez and Chris Martin, Susan Bee, Mira Schor, and more. If you are interested in this series and don’t want to miss any of it, please subscribe to A Year of Positive Thinking during this period, by clicking on subscribe at the upper right of the blog online, making sure to verify your email when prompted.

M/E/A/N/I/N/G: A History

We published 20 print issues biannually over ten years from 1986-1996. In 2000, M/E/A/N/I/N/G: An Anthology of Artists’ Writings, Theory, and Criticism was published by Duke University Press. In 2002 we began to publish M/E/A/N/I/N/G Online and have published six online issues. Issue #6 is a link to the digital reissue of all of the original twenty hard copy issues of the journal. The M/E/A/N/I/N/G archive from 1986 to 2002 is in the collection of the Beinecke Library at Yale University.