Three modest political gestures have deeply touched me this past week:

Thursday, December 9th, in London, there was a teach-in at The National Gallery in conjunction with the street demonstrations of students protesting the tripling of educational fees by David Cameron’s government.

There is a general impression, which I often encounter among my students, that activism of the 1960s variety, including demonstrations in front of public institutions, occupations of educational and other institutions, are not effective. I am not sure that is true, but of one thing I am sure: any small engagement with the kind of political activism that brings people into a room or a public space, including the street, changes the life of the individual who participates, even if that individual does not further pursue a life of activism. You are in a room with other people, people who may think like you, people who may know more than you, people who feel passionately about things you dared not admit that you did. For a moment you are not alone. It can be stressful and confusing: you can experience some of this in play in the video clip I’ve included below, lots of people talking at the same time, a contingent atmosphere, but generally polite, good-natured, and modest, even including the behavior of the museum staff (they let it happen instead of banning everyone for life). No one on this particular clip is a great speaker, that actually makes doing something like that easier to imagine. For anyone who participated, something memorable has happened. And when I look at the picture of these people joined together in the same room with one of Manet’s four versions of The Execution of the Emperor Maximilian of Mexico, 1868, I am so so envious.

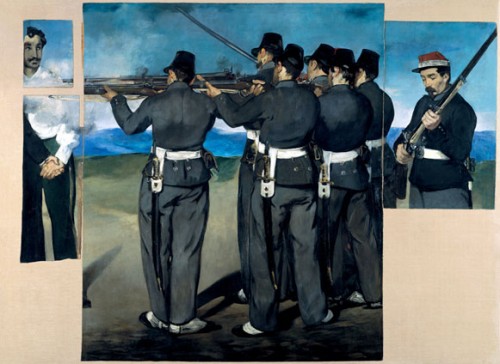

Edouard Manet, The Execution of Maximilian, 1867-68. Oil on canvas, 6'4"x9' 3 13/16", Collection of The National Gallery, London

The painting in the National Gallery that served as the backdrop for this week’s teach-in is the second in Manet’s series (see information about the history of the postmodern fragmentation of this work here). All the paintings of this series are big and they appear monumental, I’ve rarely been so struck and impressed by the size of art works. The modest scale of the exhibition space only enhanced this effect because the works were both monumental and intensely intimate in relation to the scale of each viewer.

This painting was included in Manet and the Execution of Maximilian, one of the best exhibitions held at MoMA. This small but intense, visually powerful, historically informative, wonderfully researched 2006 exhibition brought together Manet’s four paintings of this subject along with subsidiary paintings he painted during of the same year including his small but memorable painting of Charles Baudelaire’s funeral, along with a series of contemporaneous photographs of the execution and its aftermath, which were sources for Manet’s rendering and which included recreations, alterations, and falsifications of the actual, undocumented event, many of these by the ingenuity and dexterity of their photographic tricks and politically driven imagination anticipating Photoshop by over a hundred years. The exhibition also included a timeline of the events of the year Manet devoted to this work. Strangely relevant to ongoing discussions about political art (what is it? can art with overt political content be good art? does any so-called political art have any effect politically?) is also the fact that these works were not exhibited in Manet’s lifetime. So when I look at this picture of teh teach-in in London, with the painting providing a backdrop and visual anchor, I feel that the painting is fulfilling the role of a political art work in a way that Manet perhaps could not have anticipated when he painted it or when he put it away out of public view (in a gesture of pre-emptive self-censorship).

Meanwhile back in the States, this week saw a revival of the “culture wars” of the late 1980s, with the removal from the National Portrait Gallery of the video clip of David Wojnarowicz’s 1987 video “A Fire in My Belly.” There has been excellent coverage and commentary on this, including by Holland Cotter and Frank Rich of The New York Times, Blake Gopnik of The Washington Post, and Christopher Knight of the Los Angeles Times, as well as on art blogs such as Hyperallergic, and by Stephen Colbert on a must-see full show on art and censorship including a piece de resistance art critical analysis of Republican right wing Rep. Eric Cantor, totally brilliant because it could only be done with full knowledge and understanding of and ability to correctly use “The Language” or “Theory” but also devastatingly on target about the cliches that go with that knowledge and its vocabulary! & on Comedy Central!!!

But the gesture that most touched me was the quietest, a two-person protest that took place November 30 at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington:

This protest by Mike Blasenstein and the friend who filmed him Mike Iacovone was so simple: Blasenstein just stood there, with an ipad tied around his neck running the censored clip (best comment to this story on Hyperallergic, by Coco Lopes: “best use of an ipad ever.”) Blasenstein had explanatory flyers in his hand for anyone who might want one, which the museum security guards forced people to give back to him. Ben Davis published an interview with Blasenstein which foregrounds the spontaneity and modesty of his impulse to do this: “I just felt this is an important issue. I’m not really an artist or an activist, but when I heard that they took it down, it just seemed to send such a clear negative message. So I thought to myself, I would send my own message and bring this art back into the museum.” Could an instance of activism be any simpler?

The week ended with Senator Bernie Sander’s nearly 8 hour filibuster-like speech Friday December 10th, explaining and lambating the tax cut deal arrived at by President Obama and the Republican Party.

The speech can be seen on Senator Sander’s website as well as on C-Span. Here is a clip:

I only found out the speech was happening late in the day through comments on Facebook, I would have loved to watch it live but I watched about an hour and a half later that evening. I kept on trying to change the channel, thinking well , this is very interesting but let’s see if there’s something else on, but then going back to it: it was in its own plain spoken way, riveting. Sanders reminded me of the kind of politician I grew up witnessing: contrary to today’s cookie cutter hairdos with pre-fab talking points, you could count on a greater number of stalwart liberal figures, often speaking with emphatic local accents — Sanders is the Senator from Vermont but he’s from New York and sounds a lot like Bella Abzug to me — and they weren’t “Socialists” in those days, they weren’t “Independents,” they were in the Democratic Party, one of the reasons I’ve stated for being a “yellow dog Democrat.” It was fun and inspiring then, it was inspiring and a welcome respite now. I couldn’t help but think of what might happen if just one other Senator did this, and then one other one and then one other one, maybe pretty soon the cautious, craven and cowardly would begin to see a group to blend into and next thing you know you’d begin to have yourself a movement.

One can dream: each of these events is a drop of water in the worldwide tsunami of reactionary activism (tsunami, uh oh, cliche alert, but I’m thinking not only of the big crashing wave type of tsunami, but also the slowly inexorably rising water type that seems to have us suddenly clinging to lamp posts as our feet unexpectedly get wetter and wetter), seemingly, maybe even surely, futile for the moment, but still, are we not better off that a group of students and teachers occupied the National Gallery in front of Manet’s wonderful painting, and that two guys just decided to show up at the National Gallery in Washington D.C. and use an ipad for peacful protest, and that a United States Senator had the guts and stamina to give a speech that if people could hear it, they would be persuaded by it? Let’s say they are all dreamers and what they did won’t change any immediate policy. OK. But what a greater nightmare we’d be in if such people did not do such small gestures of activism.