I am interested in the capacity of material experimentation and serial practices to bring an artist to the expression of, the performance of, the actualization of content the artist had intended or desired but might not have arrived at if trust had not been put into process and materiality at some point or another. Such practices at times may seem to be unrelated to language-based theoretical structures, in particular if they involve manual processes and techniques although I am careful here to say “process” rather than “studio practice” because the latter might summon up traditional media and object-based art that in some quarters can be easily dismissed as irrelevant to contemporary issues, whereas material or methodological experimentation and serial practices can take place in any medium, including video, film, and photobased work, as well as in writing and conceptual art.

Because of my interest in process in the broader sense and because of my love of the expressive material qualities of traditional media such as ink, paper, pencil, oil, gouache, linen, wood, wax, stone, lead, copper, bronze, and more, I wanted to see Jasper Johns: Regrets, currently at MoMA even though I had a feeling I might be disappointed, despite my admiration for Johns’ earlier work and for the rigorous and rigorously private studio practice that he maintains at what is considered an advanced age for an artist, 83. Daily studio practice and engagement with craft by older artists was, literally, my matrix, and it’s my hope for my own future.

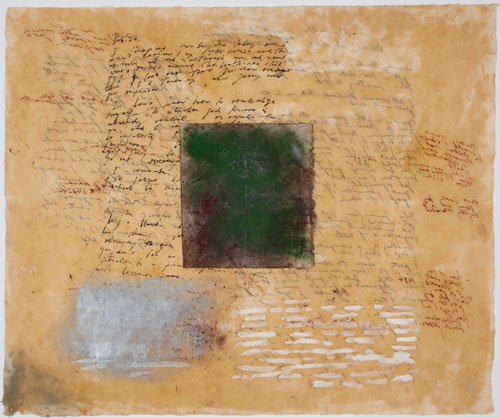

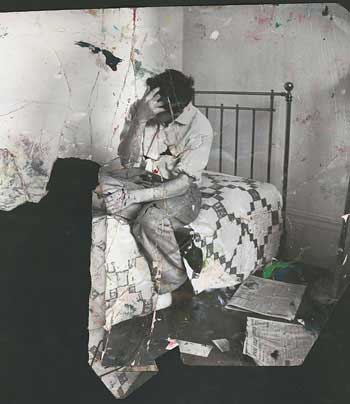

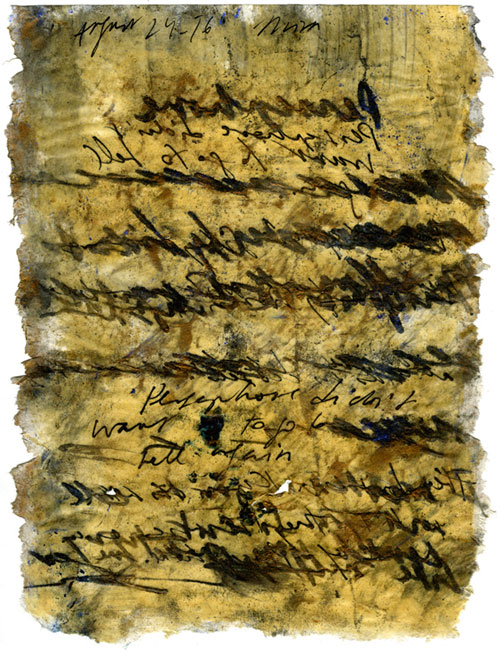

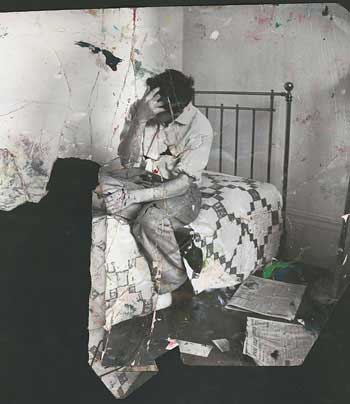

The work exhibited in Jasper Johns: Regrets is exemplary of work process in which an image is repeated and reworked using a range of techniques and materials. Johns has applied his own, oft-quoted prescription for the empty studio and the blank piece of paper or canvas, “Take an object/Do something to it/ Do something else to it/ [Repeat]” from 1964, to the crumpled, torn print of a photograph of a young Lucian Freud, commissioned by Francis Bacon for his own work process on a portrait of Freud. In the past year Johns has produced an impressive and instructive series of drawings and prints and two paintings on canvas that use this photograph as the initiatory form.

A slight pause to observe the awe-inspiring, nearly absurd monumentality of what it means that an artist can call MoMA and say something to the effect of, “I have some new work in the studio and I want to show it–at MoMA–now,” and they make it so. I had to research whether Johns even has gallery representation in New York; he does (Matthew Marks) but the call to MoMA denotes an artist who is hors combat, beyond value, who has droit de seigneur, and justly so, and it suggests an almost quaint familial intimacy with roots in another time with the institution MoMA.

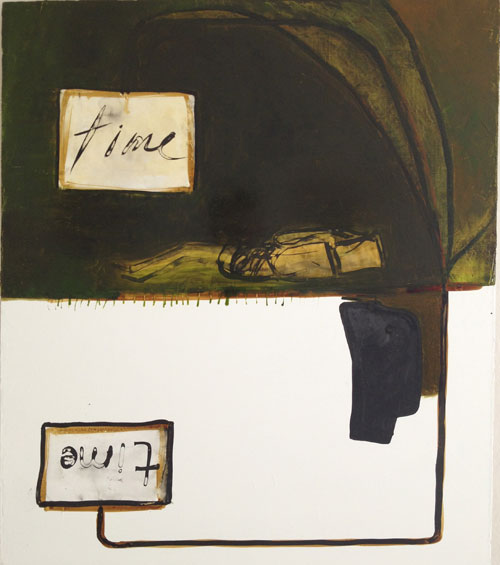

The drawings are mostly small and they take place within the strict boundary of a smaller rectangular area set on a larger piece of paper, effectively setting each drawing into an optical frame, and giving each drawing a formal quality that goes somewhat against the grain of the theme of material and subjective experimentation: Johns never draws outside the lines and there are no accidental smudges or other stereotypical indications of “work” in progress or changes of mind within an individual, except for notes to himself at the bottom of some works, in a careful, small capital letters only print in pencil: “GOYA? BATS? DREAMS?” There is a quality of carefulness and diligence in each work, with each drawing fulfilling a specific set of material specifications and formal analysis of the image. Each is a finished work, enclosed, specific, and private.

The drawings are done with pencil, acrylic, and water-color, in some cases with a Seurat-like dissolution of the figure created by the pebbly effect of rubbing a pencil over a pebbly-surfaced watercolor paper, in other cases a watery smooth print like effect is achieved through ink on a smooth and water repellent vellum like surface.

In most of the works, the pathos embodied in the photograph of Freud–a young man, his face obscured by his hand and by falling strands of hair, seated on a bed–is transferred emotively to the shape of the negative space created by the torn off bottom left hand corner of the print. In the many iterations of the image in which Johns has doubled the picture in a mirror or Rorschach-test format, the human figure is a recessive, barely legible form while the negative shape becomes an important sculptural shape, like a mesa or a tombstone.

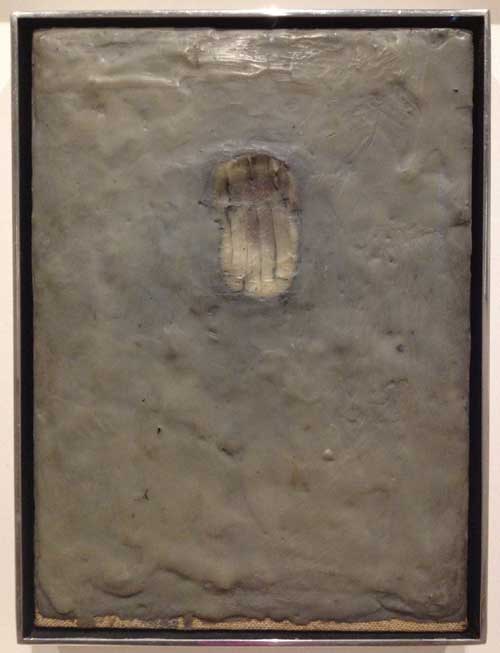

The two paintings in the exhibition have a sober, reflective quality with the monumental tombstone form of the negative space in the center framed by intimations of the recalcitrant figure. The group of work as a whole, the whole gift of a limited invitation into his studio functions as a counter-movement to mortality and knowing the age of the artist it is easy to read into the work a reflection on mortality, which is his subject I think.

Yet the work also has a funereally static quality of which the worst effect is a kind of conservatism instead of the sublime monumentality or contingent fragility that one imagines it will contain.

The problem is twofold: it is fascinating to see how the artist has taken an unprepossessing photographic scrap and rung so many changes on it yet the image upon which this edifice of studio practice is based is perhaps not all that resonant, either absolutely, or in the way he has chosen to interpret it by enhancing abstraction and deflecting figuration. Or his pressing of the appropriated image through layers of visual analysis does not actually push experimentation with materials far enough in order to get at the core of the content by his deconstruction of the given picture.

Photograph of Lucian Freud by John Deakin ©Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane/The Estate of Francis Bacon

But, now I think, perhaps I am wrong. As I write, in my mind the work becomes more interesting, the fact that the figure is so obscured and the very disciplined and precise thoroughness of the visual analysis of the appropriated image is fascinating in its rigor and in the emotional reticence. Maybe. And yet…

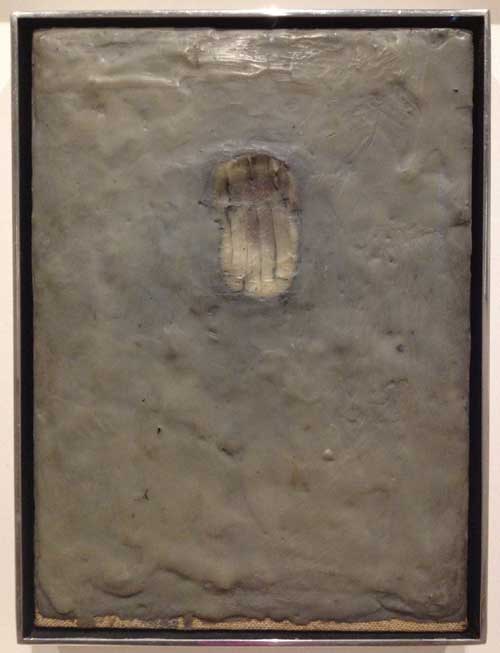

The most important moment for me was while standing to the left of the larger painting, Regrets, trying to get as close as I could to the painting surface, in the area where the seated figure is both represented and camouflaged through a web of paint marks which are neither minimal nor especially sensual: the paint quality is curiously dry with unexpected but frustrating flicks of a more sensual or at least thicker slightly less dry paint. I wish I could photograph that moment of vision, being as close to the painting as one is allowed, looking at it from one side, my vision raking it from a sharp angle to the picture plane, trying to decipher the figure, trying decode the various types of paint strokes and degrees of lubricity or aridity of the paint. It is the crux of the experience of this painting and this series of works, that the most interesting thing, the most complex, is also the least visible and, for some viewers, the most disappointing. If one thinks of this painting in relation to the characteristics of the “old age style” first perceived in late works by artists such as Michelangelo, Titian, Rembrandt, as well in late Cézanne, where the high finish of youth yields to a rougher, often more “unfinished” and therefore more modern to our eyes loose, direct, unvarnished representation, this painting both adheres to some of the characteristics of of that stylistic determination and yet goes against its grain: it is sometimes loose, but also tight, obscure, and recalcitrant. Instead it is in earlier work that one finds the characteristics of what had once been called the old age style, where the artist has no time for the niceties and goes for the gut, as in Painting Bitten by a Man, 1961, from the collection of MoMA, which was in a small but resonant two-person exhibition at Craig F. Starr Gallery last spring,Body Double: Jasper Johns/Bruce Nauman. Here is rich surface, base materialism, a mark that goes beyond indexicality to something like both cannibalism and lovemaking with the matter of paint itself.

Jasper Johns, Painting Bitten by a Man, 1961. Encaustic on canvas mounted on type plate, 9 1/2 x 6 7/8″ (24.1 x 17.5 cm),Gift of Jasper Johns in memory of Kirk Varnedoe, Chief Curator of the Department of Painting and Sculpture, 1989-2001 Copyright:© 2014 Jasper Johns / Licensed by VAGA, New York

Compared to Painting Bitten by a Man, the paintings in Regrets yield their meaning parsimoniously. I know that to compare these new works by Johns to his remarkable earlier work is to commit the unpardonable of holding a great artist to the standard of his greatest works, which came in his youth, all the more so because I respect all the work intensely, I mean not just the great early works, but the way he continues to work and to be in the world, the discipline of work no matter what stage of life’s work he is in. But I have a feeling I’m not the only person who is painting late Johns paintings in my head that are different than the ones he is actually painting.

A hint of what those might be is contained in 0-9, , one other series of works on paper in the MoMA exhibition, also done in 2013 but unrelated to the Regrets series. Nine monoprints on small pieces of rice paper represent the numbers 0 through 9, in the stencil style Johns has used many times addressing this subject. The work is done through a complex process, according to the wall text: “using stencils, rubber stamps, and textured materials–including mesh screens, rags, strings, and coins…Johns assembled each composition on an aluminum plate. He then covered these assemblages in white ink and printed them on sheets of paper. Finally he immersed the prints in a bath of black india ink, which dyed the paper but not the oil based white ink.” If one of the features of work that I love is that I want to turn on my heel and go back to my studio and work, in terms of the inspiration provided by process, he had me at “a bath of black india ink, which dyed the paper but not the oil based white ink.” By that I mean, just reading those words–“bath of black india ink”–made my pupils dilate and set my pulse racing slightly, separate even from the work achieved through that technique. But on top of that, these works themselves are delicate, simple, and there is a resonance between the method and the subject: the numbers 0 to 9 are images and concepts we recognize immediately, we know deeply, a subject that combines familiarity and neutrality so that, like the target or the flag, we can appreciate what it is that Johns is doing to them with his craft, when he takes an object, does something to it, and then does something else to it, and repeats, whereas the wrecked photo of Lucien Freud is foreign to us. Thus, although it is a resonant and mysterious image, it is also an arcane, individual, and private one, so that there is perhaps too great a conceptual and cognitive distance between the appropriated image and the material explorations of the series. I admire the work, the artifice, and even the recalcitrance of the works in Regrets, but, although I really want to, I don’t love them, I regret to say. But I will go back and stick my nose as close to the big canvas as I can and think about it some more.