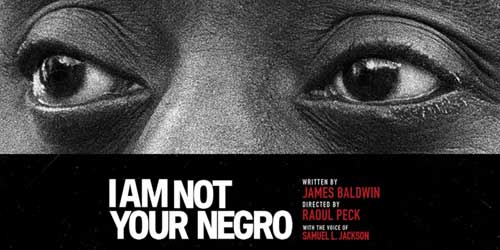

When Raoul Peck‘s new film I Am Not Your Negro began, hardly a minute or two into it, I thought, Everyone in America must see this film, it must be shown in schools, it must be required viewing. I still think so, but as the film progressed I began to doubt if the film could reach racists of all stripes–those who would admit to being racists and those who don’t–who must be reached or we hope can be reached if the country is to move forward in the direction of justice. This doubt is not because the film isn’t good, rather it is because it is so good: it is formally complex and in that way rhetorically complex as well, although the line through is direct and radiantly clear, and it is an open question whether the kind of cinematic complexity of non-linear montage praised by Walter Benjamin, Guy Debord, Jean-Luc Godard,and others for their ability to break into blind acceptance of political norms can function when popular news culture is so degraded.

I Am Not Your Negro is not a conventional documentary film by any means. It is a film essay using the words of James Baldwin to reflect upon the historical Civil Rights movement and the continued status of blacks in America, in which past (historical news footage and film clips taken from the history of popular culture since the beginning of recorded cinema) and present (violent and disturbing news coverage from Ferguson as well as lyrical footage of New York City and other landscapes from Baldwin’s narrative) fluidly intermingle. The narrative–established around an unfinished work in which Baldwin hoped to address the history of the Civil Rights movement, and more deeply the basis of our country in racism, through the lives and the deaths of three men, Medgar Evers, Malcom X, and Martin Luther King Jr., all major figures in the Civil Rights movement, all assassinated, all personal friends of James Baldwin–moves with a kind of forward motion, but the complexity of the montage creates a equally complex mirror for the citizen who must understand how she is implicated.

This little moment of doubt does not diminish my belief that this is a film that must be seen by everyone, powerful and beautiful. It is a treasure trove of important historical footage: a TV talk show hosted by Kenneth B. Clark, with Malcom X, Martin Luther King Jr., and Baldwin himself, where Malcom X attacked King as an Uncle Tom; Baldwin speaking to a West Indian Group in London in 1969; the famed debate between James Baldwin v. William F. Buckley Jr. at Cambridge University on the question: “Is the American Dream at the expense of the American Negro?”, Baldwin’s notable appearance on The Dick Cavett Show; a TV morning news talk show on the eve of the March on Washington in 1963, including, in addition to James Baldwin, Harry Belafonte, Sidney Poitier, Charlton Heston (yes!), and Joseph Mankiewicz–among other things we get a glimpse at how much serious discourse on important issues took place on network television in the 60s.

Note to subscribers: this clip can only be viewed in a browser, it will not play in an email program

At the center of the film is Baldwin himself, speaking. He is an intensely compelling figure, as eloquent at Shakespeare and as riveting a performer as the greatest actors in the history of film and theater, in what he says but also in how his intonations, the expressions of his face, his slight elegant body carry and amplify the power of his words. Each word rings like the bell of a Medieval Cathedral, crystal clear, eloquent, passionate, dismissive, razor-sharp, with a powerful use of a unique intonation and pauses that are living demonstrations of a brain sorting through complex and emotionally charged thought to find the most eloquent formulation possible, all from one of the most remarkable looking of men, a vivid expressive face, a slight small gay male body.

The script for the film is exclusively Baldwin’s own writing, taken from many sources, listed in the final credits for the film. I would love to have the script with all the sources clearly indicated. [I have not yet had a chance to see this book but it sounds like it is what I am wishing for.] This would be a uniquely useful teaching tool, to be able to show the movie and have an accompanying textbook of the script, annotated with historical context for each writing, with a timeline placing his literary and political writing into a historical timeline, something that the film does impressionistically and synecdotally, through an inspired usage of very diverse film clips.

Thinking of all the different clips and photos, it occurs to me that it may be important to say this film is the anti-Ken Burns: no offense to Burns’ signature style, but this blows through pan and scan. You never feel comforted by the formulaic.

The narration of Baldwin’s text is by Samuel L. Jackson. Since I have long been familiar with Baldwin’s own voice and intonations, it was at first a bit trying to hear his words read in a precise yet somewhat uniformly mournful tone by Jackson, a voice which pales in comparison to Baldwin’s powerful use of cadence and his entire physical affect, but the words are so true to our current situation that the narration is more powerful than the reader.

The film has so much to teach about race relations in the United States not just historically but today. In recent months some have been surprised to find that there are so many organized groups of Neo-Nazis all around the country, so it is revelatory, again, to see pictures of young white men in the South openly carrying swastikas in the 1950s and 60s. The film brings terrifying recent footage of militarized police presences together with the police violence of the 1950s and ’60s–the police weren’t as padded and militarized in their dress and equipment as now but they were just as violent–and the film also reminds us of just how violent a decade the 1960s was. This reminder is complex and troubling: on the one hand we survived that time period and during it, as a result of struggle and strategy, there was some distinct movement towards voting rights and opportunity, though at the time Baldwin, like Malcom X, warned against believing any of that was anything more than window dressing, that any of it truly addressed the underlying foundation of the country in racism, slavery, and oppression. Nevertheless, as someone who came of age in terms of political awareness during the ’60s and ’70s, there was still a governmental structure that eventually, under great pressure, grudgingly, responded. But then the doubt comes, which is affecting us all: is there anything left today in the halls of government and private power of that even grudging decency and respect for constitutional rights.

Looking at the archival footage of civil rights demonstrations of the 1960s, including the actions of the children of Birmingham in 1963, you get a strong sense of the strength that comes from knowing who you are and what you are fighting for, and from carefully considered and organized education and training of all participants no matter their age, lifted by song and inspired by eloquent political and religious speech, including that of Baldwin himself, song and speech which resonate to this day.

I literally ran in the street to make the 4PM showing at the Film society of Lincoln Center yesterday. I advise you to run too. Everyone must see this film.