The theme of my previous post, “Still ‘Naked By The Window,'” was the fascination of watching patriarchy take care of its own, in this case tracking the orchestration of efforts, over a period of years, to restore Carl Andre’s personal reputation in advance of his retrospective at Dia, there being no question of needing to restore his artistic reputation which is unquestioned and secure. One step in this process was the publication of “The Materialist,” Calvin Tomkins’ December 5, 2011 New Yorker profile of Andre.

As a result of my post, I was made aware of two letters to the editor of the New Yorker that were sent immediately following the publication of Tomkins’ profile. One was from Mendieta’s gallerists, Mary Sabbatino of Galerie Lelong in New York and Alison Jacques of Alison Jacques Gallery in London, and from Mendieta’s sister and administrator of her estate, Raquelin Mendieta, and one from art historian Abigail Solomon-Godeau. Neither letter was published.

The letters are both interesting, they go over similar points but with important different emphases and information, and they contain material that I was not able to articulate as knowledgeably in my brief text. It is important to know what these letters contain, but also important to know that these letters were not published. It is important to know how hierarchies are maintained as much by what is left out of the historical record as by what is allowed in. It is in that spirit that I asked for permission to reproduce these letters here for the record and I thank the signatories for allowing me to do so.

*

From: Mary Sabbatino

Sent: Wednesday, December 07, 2011 8:45 PM

To: themail@newyorker.com

Subject: Letter to the Editor

Letter to the Editor: re: December 5, 2011 Calvin Tomkins “The Materialist”

It is disturbing to read how easily Calvin Tomkins, one of the most respected and beloved journalists of our time, fell sway to the same strategy of blaming the victim as was employed by Mr. Andre’s defense team in Ana Mendieta’s murder trial. Equally alarming from a writer and editorial team of such caliber is the repeated presentation of conjecture or opinion as fact “(an) artist who fell from the bedroom window”, “loneliness made Mendieta a rebel,”… “her anger spilled over in public..”– and the omission of crucial facts about the murder investigation. Mr. Tomkins characterizes Mendieta;s art as “morbid”, but would he use the same pejorative lens when discussing a male artist dealing with violence in his work? Regrettably, this reveals an underlying bias, in which Mr. Andre is repeatedly portrayed with positive attributes and Ms. Mendieta with negative ones.

Mr. Tomkins omitted two notable points from Mr. Andre’s recollection of the event. According to Mr. Andre, whose present memory differs significantly from his contemporaneous statements, Ms. Mendieta lost her balance in the action of opening a stuck window in their apartment and fell to her death. This story is in direct contradiction with Mr. Andre’s recorded conversation with the 911 Operator on the night/early morning of Ms. Mendieta’s death. Mr. Andre told the operator that he and his wife were watching television and began to argue, that she went into the bedroom and he followed her. Mr. Tompkins may not have been aware that when the police came to the apartment they noted scratches on Mr. Andre’s face and that no footprints nor fingerprints by Ms. Mendieta were recovered on the windowsills. Because of irregularities with the police’s collection of the evidence and with the search warrant, neither was admissible in the trial, but both were part of the pre-trial hearings. As evidence of Mr. Andre’s community of support, Mr. Tomkins points out that none of Mr. Andre’s former companions would testify against him, but this is not the only possible interpretation. Richard Finelli, the detective who investigated the case for the prosecution, told the artist’s sister, Raquelin Mendieta, that many were reluctant to testify because they feared a negative effect on their art careers.

We are rightly horrified when a woman in Afghanistan is “pardoned” for rape but must marry her rapist. We should reserve at least a shred of indignation that Ana Mendieta’s character, as many victims of rape or domestic violence find out, is on trial all over again.

Sincerely yours,

Mary Sabbatino,

Vice President, Galerie Lelong, New York

Alison Jacques, Alison Jacques Gallery, London, UK

Raquelin Mendieta, Administrator, Estate of Ana Mendieta, Los Angeles, CA

*

To the editor:

Unlike all of Calvin Tomkins’ essays on contemporary artists, his recent one on Carl Andre must necessarily discuss the circumstances by which the artist faced the charge of homicide. Acquitted on the charge after two trials, and as all who have written on her death (Tomkins included) acknowledge, the truth of what happened that night will never be known by anyone except by Andre. In this respect, Andre’s own memories seem surprisingly more detailed now then they were at the time of his trials, as the transcripts reveal. This, despite his current problems with memory loss as a result of a fall two years ago. Tomkins’ characterization of Andre as an “invisible” figure in the art world is absurd. His work sells for huge sums, is housed in museums throughout the world, and is discussed in greater or lesser detail in every survey book on contemporary art in the English language. His bibliography is substantial. Dia does not exhibit “invisible” artists.

That said, I am writing only to remark that Tomkins’ treatment of Mendieta, both as an artist and as a person, is in depressing conformity with a certain narrative first developed in the mass media. In this scenario, Mendieta’s ethnicity and character (i.e., young, hard drinking, tempestuous Latina), her own artistic stature (null, aside from her grants) is contrasted with Andre’s own commanding reputation as an internationally lauded and indeed, canonized figure within contemporary art.

Given the figures marshaled in his legal defense, not a few people declined to testify, thinking of its possible effects on their own artistic reputations. Thus, the inequities embodied in the trials themselves are skirted. Although no one was privy to the events of her death, Andre’s character witnesses were a Who’s Who of the art world’s most powerful artists, gallerists, museum professionals, and critics; this tells its own story about art world politics. On the side of the prosecution, a Cuban American family and (implied by Tomkins) some vindictive feminists, a cabal of which, as Tomkins implies, have, like the furies, spitefully pursued the stoically laconic artist.

For the record, too, I would like to mention that Mendieta’s artistic reputation, ended at the age of 36, is constantly growing and is, of course, posthumous.

Sincerely yours,

Abigail Solomon-Godeau

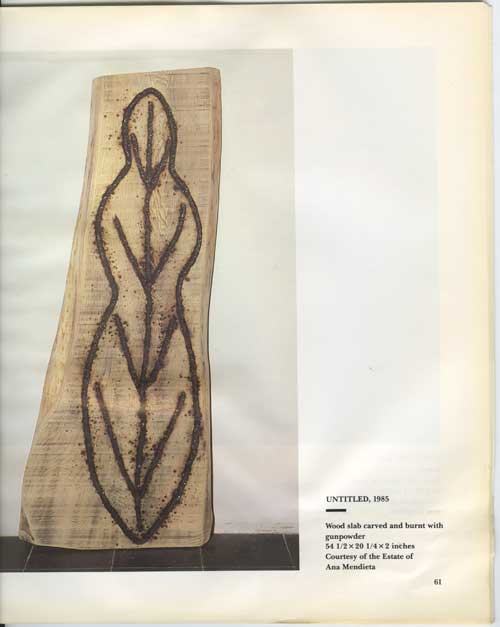

Ana Mendieta: a retrospective, catalogue, New Museum 1987