The sad news of the death of British psychotherapist and feminist art historian Rozsika Parker provides the opportunity to bring her work to the attention of anyone interested in feminism, art, and women artists. Parker was a pioneer feminist art theorist and activist from the early 70s to the 90s, often collaborating with the art historian Griselda Pollock.

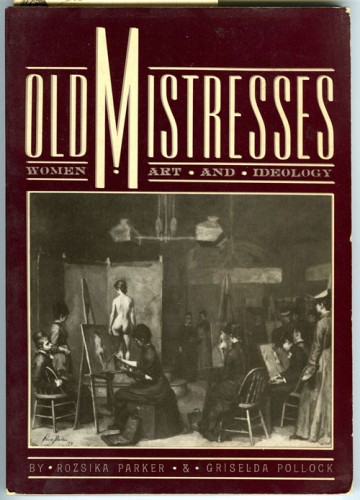

I consider Old Mistresses: Women, Art and Ideology, which Parker and Pollock co-authored, one of the most important books of feminist art theory and history that I ever read: Parker and Pollock examined how art history as a discipline had misogyny at its core, almost as one of its foundational purposes, with all its terms of value strongly gendered to condemn anything that smacked of the so-called feminine, although of course behind the naturalized frame of universalist neutrality. Their second collaboration, Framing Feminism: Art and the Women’s Movement 1970-1985 was and is a great source of information about the feminist art movement in Britain, which sometimes got overwhelmed by the American Women’s Liberation Movement’s belief in its own unique importance. Parker’s The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine is also a very influential and still relevant book, considering how much we now may take for granted that knitting or embroidering or weaving are acceptable media for high art, instead of being seen as crafts or as the hobby of well brought up girls or domestic servants.

Parker was a bit of a mysterious figure for all of us in the United States who admired these books because Griselda Pollock was the public figure of the two in the context of the art world and academia, speaking at many art history symposia here in the US, while Parker continued her feminist activism working as a psychoanalytic psychotherapist in Britain. Because it has been possible to follow the development of Pollock’s feminist ideology and aesthetic views in the books she wrote without Parker, I always have been curious about Parker’s role and voice in their collaboration and have tried to intuit it in the way one measures a black star, almost by negation, by what was not Griselda Pollock. I formed an image of a fierce feminism tempered by a compassionate focus on the work and the cultural issues affecting women, in life and in history, rather than the approach which won out in the 1980s, one that negated the “theoretical” existence of the (biologically determined) category “Woman” in favor of an interest in (socially constructed and non-biology specific) gender.

Sadly Old Mistresses and Framing Feminism have long been out of print. I hope that they can be re-issued because the passion and clarity and sheer historical data in these books would be of great interest to young women artists now.