In my previous post, “Invisibility and Criticality in The Imperium of Analytics,” I discussed the personal background and implications of the rating of Criticality 95, Visibility 5 that I received from artist William Powhida this past winter. In this post I examine further some of the conditions of writing and publication for me when I first started to publish and today.

The Imperium of Analytics

Because of the instantaneity of online publication [particularly the case for self-administered blogs with no editorial filters beyond the blogger], there is an expectation of instantaneous response. If you don’t get it, you’re incensed–at any rate I am, that is until I remind myself that I don’t read most of what comes my way via links on Facebook and email because I can’t keep up, I don’t understand how anyone else does (more on that in a minute). Or, put another way, you can see right away if you have not gotten instantaneous response, since you can track reception and readership by the day, even by the minute: how many “likes” clicked on Facebook, how many views, shares, and comments on Huffington Post, Google +1, how many re-Tweets, and finally, the daily Google Analytics graph that tracks blog readership.

![]()

As you can see, in the case of this blog, the graph drops abruptly within a day or two after a post. If you don’t write anything for a few days, it flatlines.

When Susan Bee and I published the biannual journal M/E/A/N/I/N/G from the mid-1980s to the mid-90s (the history of our friendship, our collaboration on M/E/A/N/I/N/G, and the reasons for founding the journal are detailed in our “Introduction” to M/E/A/N/I/N/G: An Anthology of Artists’ Writings, Theory, and Criticism), we would work on the final proof of each issue in a concentrated fashion for a couple of months, having gathered material for a couple of months before that, following up on questions we and other artist/writers around us had about artmaking and the artworld of that time but with no artworld schedules in mind.

Our magazine was distributed partly through a small-journal distributor whose public manifestation was Niko’s Smoke Shop at the corner of Sixth Avenue and 11th street, a tiny crowded space that could well have doubled as a CIA drop, and partly by Susan and I ourselves lugging heavy, filthy Post Office mail bags filled with our subscribers’ copies to the nearest Post Office that would accept the non-profit permit we were able to use, where after a clerk would put us through the maximum of bureaucratic hell in his or her small power, we would leave feeling we had just thrown our hard labor down a well. In fact one time early on we had to leave the Post Office after we had deposited our magazines after much bureaucratic interrogation and corrections, paid but not yet gotten our change or receipt, because they thought the station was on fire and when it turned out it wasn’t, they decided to close the station anyway so they could get the rest of the day off! A worker took pity on us and handed us our change through the half-shut back door to the street.

After this thoroughly analog ordeal in the distribution process, reader responses were equally analog, if any: a short note scribbled on one of our subscription slips, the occasional out of the blue phone call, or actually running into one of our readers in the street.

When our first issue came out, containing my essay “Appropriated Sexuality,” in which I critiqued both David Salle’s representation of women in his paintings and the complicit critical apparatus supporting this work, the phone rang and a woman introduced herself as Carol Duncan, one of the art historians I admired tremendously and held as a model for my writing: “Who are you?” she asked. What a thrill.

Shortly after we published my essay “Figure/Ground” in M/E/A/N/I/N/G #6 in 1989, an essay in which I posited that a primal, somatized disgust with the “goo” of paint underlay the supposedly objective critique of painting as a relevant medium for contemporary expression (in the process attacking some of the powerful critical voices of October magazine as “aesthetic terrorists”), I ran into a fellow painter, Guy Goodwin, in the Canal Street Post Office at the end of my block in Tribeca: “I just love that essay about goo,” he drawled in his deep Alabama accent.

This kind of analog response made us feel that we were part of a real community. It was small but tangible in a way that gave a stable and organic basis to what we were doing. And for me, those few interactions with individual readers were present and precious, but aside from that I had little idea of who was reading what I wrote and little expectation of finding out. Time was longer. In fact, as an amusing aside, I wasn’t absolutely sure that Salle himself had read “Appropriated Sexuality” until 7 years after its publication, at which point I felt I had lobbed a canon ball by hand and it had taken 6 or 7 years before it finally landed behind enemy lines.

At the same time the relative paucity or slowness of response was not always a good feeling, but it also insured, it almost enforced a private space for the development of ideas, a move onto new research rather than an absorption in what I had just written.

“Figure/Ground” lurked in my mind for a couple of years and then took more than a year to write and it came out a year after a previous essay in M/E/A/N/I/N/G. Now if I let two weeks go by without writing something new I feel a biological impulse and a commercial imperative for some kind of author’s equivalent of first aid biofeedback to keep the graph line up. The longest I’ve worked on a blog post on A Year of Positive Thinking has been about two months, though of most that just thinking about it on the back burner, with the actual writing compressed into a few days, and even the quickest entries require a full day’s work chained to the computer all day, in my nightgown, without ever leaving the house. I’m not sure I could write an essay like “Figure/Ground” today, but I’m certain I couldn’t do it in two weeks or two months.

Even though I’ve embraced the challenge presented by the blog format and the time frame of the web to try to keep in the current discourse as at close to its requirement of instantaneity as possible, it’s likely that I’m trying to do something perhaps antithetical to this ecosystem: I’m drawn to creating a hybrid text in which a contemporary spark, my penchant for associative thinking, and my enjoyment of research are compressed into an accelerated research and writing process in order to hit the stream of the web within its time frame. I’m trying to get to what I want to say as quickly and as succinctly as I can but the nature of my particular intervention even when compressed and accelerated may go against the grain of its current medium.

Granted, blogs are meant as a vehicle for instant commentary, less formal than even the newspaper article or column so that increasingly even professional journalists who already work in a much tighter relation to the time frame of the news cycle are adding a blog to their newspaper or journal profile for even quicker, though possibly less digested or edited reaction to news. Blogs get better analytics stats if they come out everyday or even several times a day, to establish a brand presence, and I would guess that it hardly matters what the content is, although many are interesting and useful to their audience.

I appreciate the aplomb or maybe it’s the sang-froid of someone like Raphael Rubinstein on his blog The Silo: Rubinstein’s stated aim is to, occasionally and according to no apparent calendar or exhibition schedule, write usually quite short texts that “challenge existing exclusionary accounts of art since 1960 and to offer a fresh look at some canonical artists” that you may or may not have heard of such, from Daniel Spoerri to Biala. At the same time, I appreciate blogs that keep me informed about a wide range of art and art news, such as Hyperallergic; painter Sharon Butler‘s blog Two Coats of Paint; and critical writing that does keep current with art exhibitions but in an idiosyncratic way, like painter Bradley’s Rubenstein‘s reviews on Culture Catch.

Expectation of instant response is paired with expectation of instant reading. As a reader it is hard to keep up with the surfeit of material that comes at you everyday from every source and of every register of writing, from academic research to news editorials to entertainment gossip. I don’t understand how anyone keeps up. But it’s clear that shorter is better, you maybe can read a few things online a day if they are 100 words long, 700 is the limit recommended to its bloggers by The HuffingtonPost, you are probably not going to be able to read 2000, much less 4000 (this post weighs in at a hefty 2672, so if you’ve gotten this far, dear reader, you are definitely above average!). Oh by the way, Google analytics also tells you the average time people spend on your site:

![]()

Oops! Now I know how people keep up or try to with the daily flood of links. A minute is about enough time to find out that Arnold isn’t giving Maria alimony. No, actually that took about 5 seconds, so I guess a full minute is a web eternity. The Huffington Post Arts page launched a “Haiku Reviews” section last year but checking the site today there seems to be some slippage from the definition of 17 syllables, because in classic form the haiku requires rigorous and exquisite concentration of ideas into each word–a reduction that takes time to refine, distill, and compose. In 2000, curator Stuart Horodner put together “Haikuriticism – 17 Art Reviews (in 17 Syllables) by 17 Writers,” in Art Issues #63: he sent me a couple of the Haikuriticisms today. About “Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt at Met” I wrote : “Little girl mummy/ ‘Why can’t you grow when you’re dead?’/ Encaustic flesh can”; Amy Sillman on Will Cotton: “Photorealism?/Audrey Flack was much better?/(Not a cute boy, though.)”; and Katy Siegel on Chuck Close: “Agnes said to Chuck,/”I’m ready for my close-up.”/They know grid is good.”

Of course, the analytics graph rises highest when the post is about things, people, artists that everyone already “likes” so their likability will rub off on you, or things that have a frisson of the prurient or the scandalous. Links to names that attract search engines and to websites with a lot of traffic will bring traffic to yours. It also is important that the post be in response to the immediate news cycle. This focus on the immediate shrinks the writing time further because you know that if you don’t intervene in a timely manner, now, another story will push this one aside. Add to that the preference for the known and already liked and alternative stories or ways of thinking–or “think pieces”–are of course even more likely to be pushed aside, especially if they are not likable, that is to say, not positive–hence the title of my blog, which is at once perfectly sincere in its goal but inevitably ironic. The impact of this system on art discourse and politics is quite evidently disastrous, since both political events and artworks are quickly dropped before their meanings are really sorted out while the implications of the “old news” continue to influence the present, whether we see it or not.

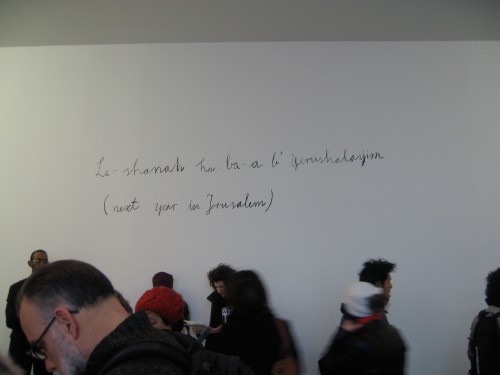

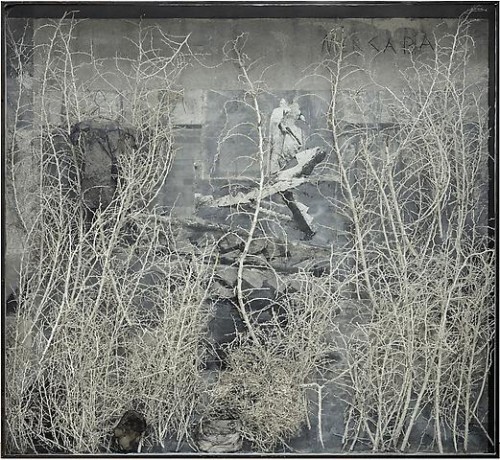

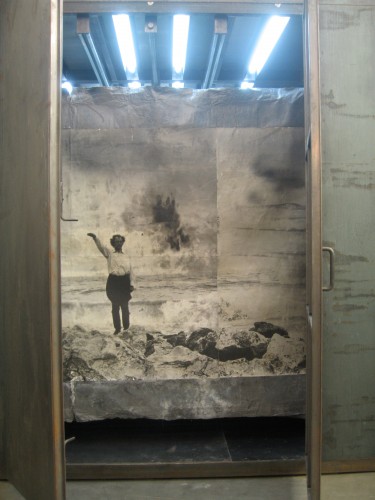

Of my writings published online on this blog and The Huffington Post since last April 2010, the ones that have in any small way gone viral, very relatively speaking, were those in which I wrote fast enough about current hot news items or ones relating or engaging with artworld celebrities: as one example, “My Whole Street is A Mosque,” written within 24 hours of the news cycle surrounding the proposal for a Islamic cultural center near Ground Zero, was picked up by various web aggregators; “Looking for Art to Love, MoMA: A Tale of Two Egos” also did very well because of my speculation about how or whether Marina Abramovic peed during her performance “The Artist is Present” at MoMA, a subject of much prurient curiosity (interesting speculation was illustrated online at New York Magazine and resolution of the mystery came in the Wall Street Journal’s blog, “Speakeasy”); “Anselm Kiefer@Larry Gagosian: Last Century in Berlin,” where I tucked a critical response to Kiefer’s recent show into a bit of reporting about how Gagosian Gallery was using the NYPD as its private police force, also created a spike on my Google analytics; more recently I could perceive a noticeable uptick in my readership as well as in the number and enthusiasm of my Facebook friends’ comments for “Should we trust anyone under 30?,” most likely because it was written in relation to a piece by Jerry Saltz and because Jerry participated in the comments discussion to this post on Facebook, bringing his devoted fan base with him.

As I write this blog post I’m reading Give My Regards to Eighth Street, the quite delightful collected writings of the American composer Morton Feldman. A wonderful sentence at the beginning of his 1965 essay “The Anxiety of Art” falls into my lap. The essay caught my attention today, the day the awful debt ceiling agreement has been reached in Washington, D.C., because Feldman begins with the figure of Dr. Zhivago as a figure whose “identity is crushed by history,” and here we are in a summer which feels to some of us like the summer of 1939, a fake calm after war has been declared, a summer of the most glorious weather in European history before the cataclysm, though for us the cataclysm is of a nature that perhaps is more like the summer of 1929 or maybe that of 1933, economic and ideological wars on the individual and ideals of an egalitarian society. Shifting from the large scale cataclysms of history, Feldman shifts to the impact of history on art:

We see it in life; why do we fail to see that in art too, the facts and successes of history are allowed to crush all that is subtle, all that is personal, in our work?

Yet the artist does not resist. He identifies with this force that can only destroy him. In fact, it has an irrisistible attaction for him, in that it offers him known goals, the illusion of safety in his work, the tempting knowledge that nothing succeeds in art–like someone else’s success. In a word, because it relieves the anxiety of art.

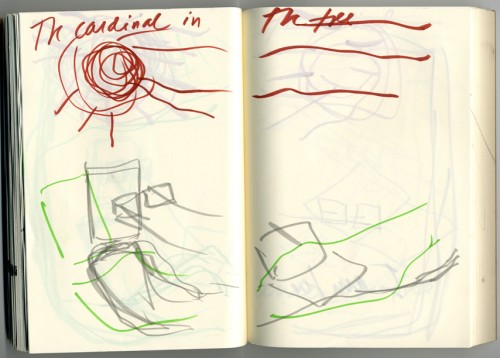

Mira Schor, Sketchbook Drawing, August 2, 2011, in sympathy with Morton Feldman’s distinctions between sound and noise

If your eye is on the imperium of the news cycle and of the instant tracking number capabilities of analytics, market /entertainment/promotion/herd positivism dominate. The subjects that take hold on the web are news about news, news about celebrity, already tied to the market’s tastes and schedules, feeding the known rather than exploring the unknown, critically or otherwise. To maximize your “like” clicks and keep your analytics from flatlining, best to write about things that everyone already knows and likes.

One of the nicest responses to A Decade that never made it into a review was from a fellow painter who wrote to me, “you are writing things I feel like I’ve been wanting to hear for a long time but didn’t know it.”

It goes without saying I hope you have “liked” this post.

*

The conditions of contemporary publication on the web that I’ve touched on here have made me interested in researching the conditions of the writing and publication of two essays I particularly admire and yet whose publication has always seemed in some sense mysterious to me. These are two essays by John Berger that are among my favorites, both included in Berger’s 1988 book of collected essays, The Sense of Sight: “The Moment of Cubism,” originally published in the 1969 book of the same name, and “The Hals Mystery,” originally published in the British journal New Society in December 1979. I will discuss these in my next and third post in this three part series, “The Berger Mystery,” coming soon.