I have been teaching art since I was 22 and still a graduate student myself. Teaching is part of the way my mind is structured and I think that teaching includes learning, or continuing to learn. At this point I feel that learning might best be pursued without the pressures of teaching, but that is another story. The rest of the story is something I am considering putting into a book that would use my teaching archive as a starting point for short reflections that would situate the teaching ideas of past moments in relation to current ideas.

I recently went through my large file cabinet because I needed to find a document with some important log-in information, which naturally was not in the file cabinet though I did eventually find it in a pile on the cabinet, which by the way normally I can’t open because of several overstuffed rolling file cabinets parked in front of it with piles of papers on top of them. Instead I went through folders of teaching materials, syllabi, but mainly all the essays that I have taught on feminism, painting, early modernism, minimalism, Fluxus, Debord, Space (exhibition space), and more, each grouping including the original xerox if a PDF version has not been found online or scanned yet, and my heavily annotated teaching copies.

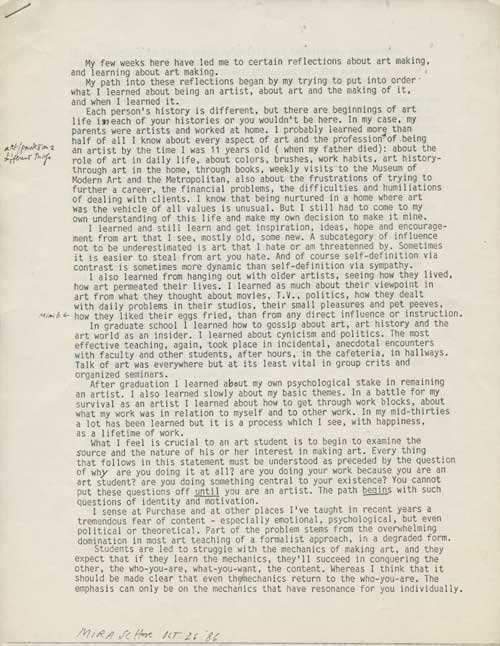

In a folder of random material, I found a statement that I seem to have written for a class I taught at SUNY Purchase in the fall of 1986. I have no recollection of what the circumstances were, or whether I read this or handed it out. The statement is dated October 26, 1986, which I think is the day I wrote it, which was a Sunday, for a class at Purchase the next day.

Texts I wrote shortly after this one, such as “On Failure and Anonymity,” [Heresies 25, 1990] explore similar territory particularly in relation to art market pressures. Teaching is situational and interventional so I assume that this statement was written to address some issues that had come up in a specific class and, if written today, such comments would be less uniquely focused on material and formal production of art objects and less specific to painting. In fact ten years later I wrote and produced a videoscript to express my disgust at MFA students who were rebelling against reading the fairly moderate composite of classic modernist and postmodernist texts I was assigning to them. One point of my book would be to point to the extreme reversals that can take place in art and therefore in art education, necessitating for the teacher historical self-awareness and the ability to adapt while maintaining one’s core values. So on the one hand in the past years I have taught in a situation where political, theoretical, identity-based content is the primary line of instruction and where issues of form and style including the development of form in Western art history have been to a great extent reduced for the students to free-floating appropriatable photo images unrelated to any materiality, context, or struggle to achieve form. On the other hand issues of history, style, form and materiality still do matter in individual works and even in terms of achieving market success and my emphasis on these concerns made sense not only to my own work in the early 80s but also in the context of Purchase at that time more than to my own more conceptual and political graduate education at CalArts.

Thus despite completely different artworld conditions, educational philosophies, and theoretical discourses, a lot still resonates for me in this statement, and I can read through it my continued concern about how hard it is to continue to make art at all much less grow as an artist once one leaves school.

I wrote:

My few weeks here have led me to certain reflections about art making, and learning about art making.

My path into these reflections began by my trying to put into order what I learned about being an artist, about art and the making of it, and when I learned it.

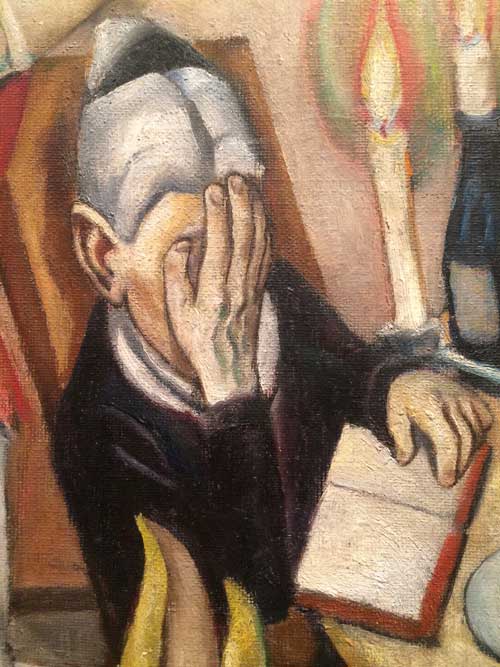

Each person’s history is different, but there are beginnings of art life in each of your histories or you wouldn’t be here. In my case, my parents were artists and worked at home. I probably learned more than half of all I know about every aspect of art and the profession* of being an artist by the time I was 11 years old (when my father died) [*art and profession two different things]: about the role of art in daily life, about colors, brushes, work habits, art history–through art in the home, through books, weekly visits to the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan, also about the frustrations of trying to further a career, the financial problems, the difficulties and the humiliations of dealing with clients. I know that being nurtured in a home where art was the vehicle of all values is unusual. But I still had to come to my own understanding of this life and make my own decision to make it mine.

I learned and still learn and get inspiration,ideas, hope and encouragement from art that I see, mostly old, some new. A subcategory of influence not to be underestimated is art that I hate or am threatened by. Sometimes it is easier to steal from art you hate. And of course self-definition via contrast is sometimes more dynamic than self-definition via sympathy.

I also learned from hanging out with older artists, seeing how they lived, how art permeated their lives. I learned as much about their viewpoint in art from what they thought about movies, T.V., politics, how they dealt with daily problems in their studios, their small pleasures and pet peeves, how they liked their eggs fried, than from any direct influence or instruction.

In graduate school I learned how to gossip about art, art history and the art world as an insider. I learned about cynicism and politics. The most effective teaching, again, took place in incidental, anecdotal encounters with faculty and other students, after hours, in the cafeteria, in hallways. Talk of art was everywhere but at its least vital in group crits and organized seminars.

After graduation I learned about my own psychological stake in remaining an artist. I also learned slowly about my basic themes. In a battle for my survival as an artist I learned about how to get through work blocks, about what my work was in relation to myself and to other work. In my mid-thirties a lot has been learned but it is a process which I see, with happiness, as a lifetime of work.

What I feel is crucial to an art student is to begin to examine the source and the nature or his or her interest in making art. Every thing that follows in this statement must be understood as preceded by the question of why are you doing it at all? are you doing your work because you are an art student? are you doing something central to your existence? You cannot put these questions off until you are an artist. The path begins with such questions of identity and motivation.

I sense at Purchase and at other places I’ve taught in recent years a tremendous fear of content–especially emotional, psychological, but even political or theoretical. Part of the problem stems from the overwhelming domination in most art teaching of a formalist approach, in a degraded form.

Students are led to struggle with the mechanics of making art, and they expect that if they learn the mechanics, they’ll succeed in conquering the other, the who-you-are, what-you-want, the content. Whereas I think that it should be made clear than even the mechanics return to the who-you-are. the emphasis can only be on the mechanics that have resonance for you individually.

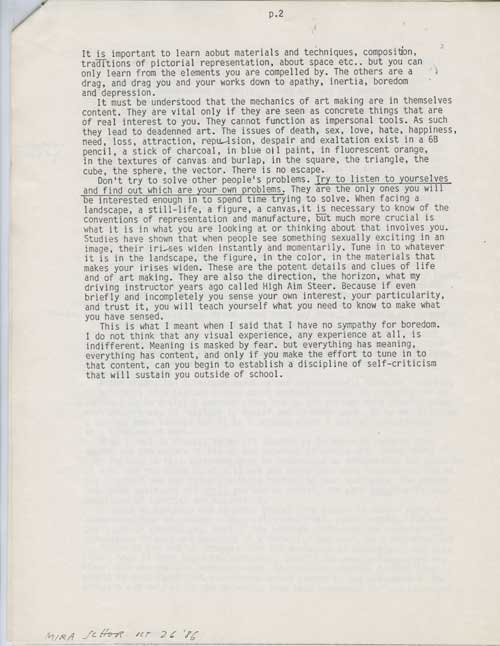

It is important to learn about materials and techniques, composition, traditions of pictorial representation, about space etc… but you can only learn from the elements you are compelled by. The others are a drag, and drag you and your work down to apathy, inertia, boredom and depression.

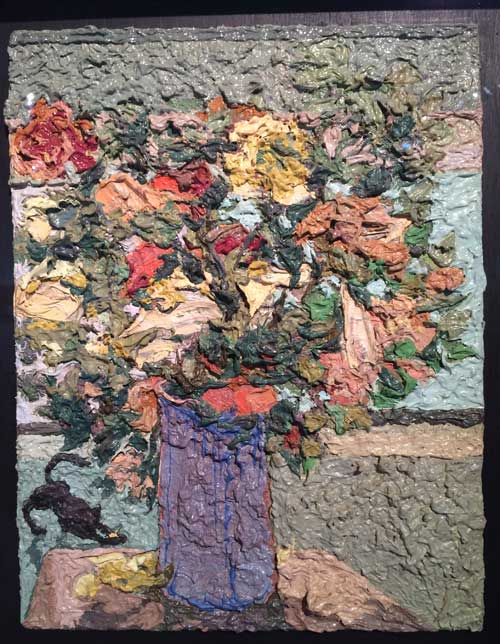

It must be understood that the mechanics of art making are in themselves content. They are vital only if they are seen as concrete things that are of real interest to you. They cannot function as impersonal tools. AS such they lead to deadened art. The issues of death, sex, love, hate, happiness, need, loss, attraction, repulsion, despair and exaltation exist in a 6B pencil, a stick of charcoal, in blue oil paint, in fluorescent orange, in the textures of canvas and burlap, in the square, the triangle, the cube, the sphere, the vector. There is no escape.

Don’t try to solve other people’s problems. Try to listen to yourselves and find which are your own problems. They are the only ones you will be interested enough in to spend time trying to solve. When facing a landscape, a still-life, a figure, a canvas, it is necessary to know of the conventions of representation and manufacture, but much more crucial is what it is in what you are looking at or thinking about that involves you. Studies have shown that when people see something sexually exciting in an image, their irises widen instantly and momentarily. Tune in to whatever it is in the landscape, the figure, int eh color, in the materials that make your irises widen. There are the potent details and clues of life and of art making. They are also the direction, the horizon, what my driving instructor years ago called High Aim Steer. Because if even briefly and incompletely you sense your own interest, your particularity, and trust it, you will teach yourself what you need to know to make what you have sensed.

This is what I meant when I said that I have no sympathy for boredom. I do not think that any visual experience, any experience at all, is indifferent. Meaning is masked by fear, but everything has meaning, everything has content, and only if yo make the effort to tune in to that content, can you begin to establish a discipline of self-criticism that will sustain you outside of school.

Mira Schor, Oct.26, ’86

*

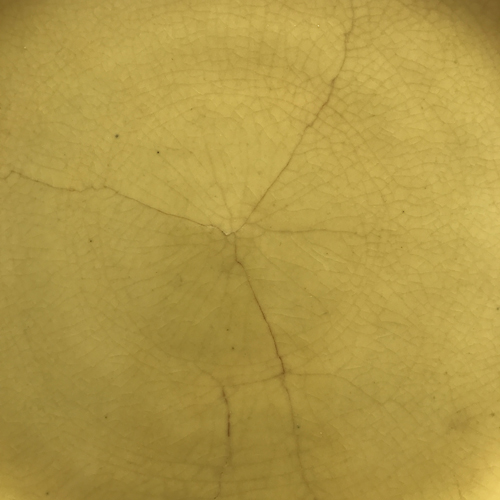

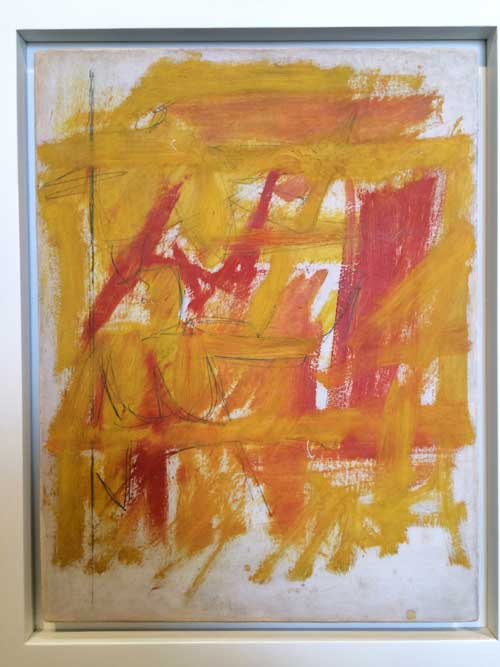

Just out of curiosity I wondered what I was working on at the time I wrote this statement. Here is Walking Tuning Fork, dated November 10, 1986

Mira Schor, Walking Tuning Fork, 1986. Oil on 5 canvases, 80×12 inches overall dimension