August 1, 1984

How much more Orwellian is 2013 than was the actual year 1984, or so it seemed when I did my calendar paintings in 1984.

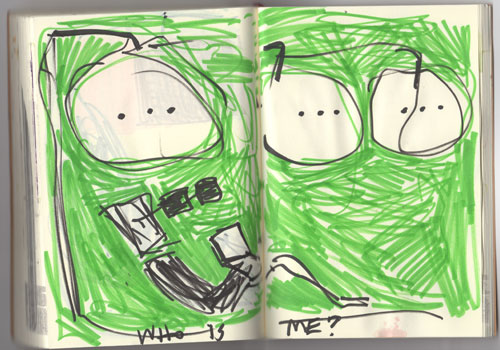

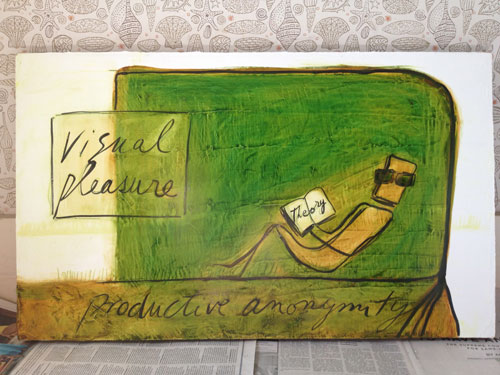

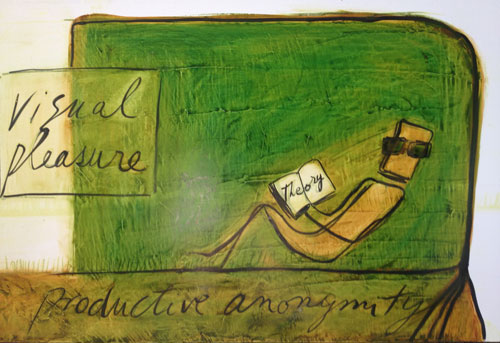

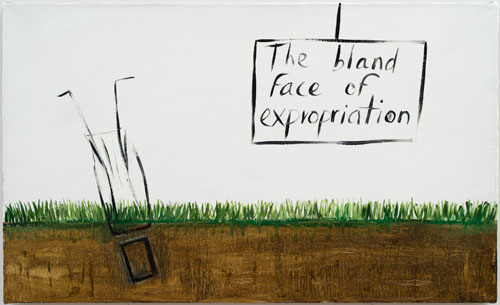

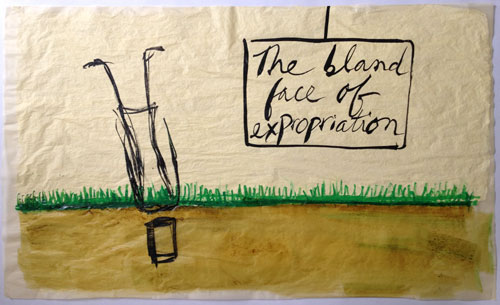

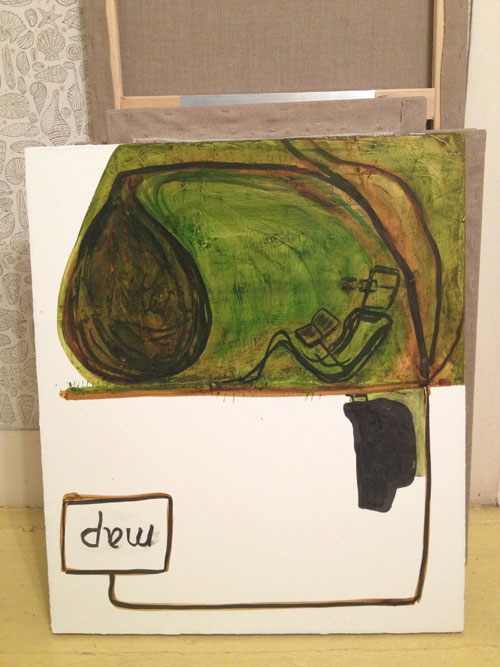

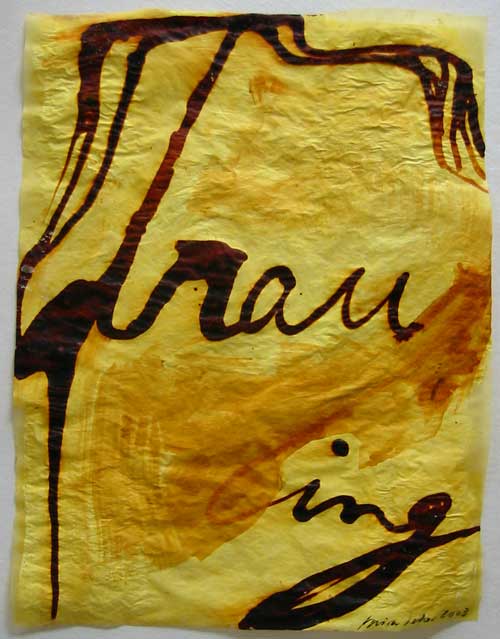

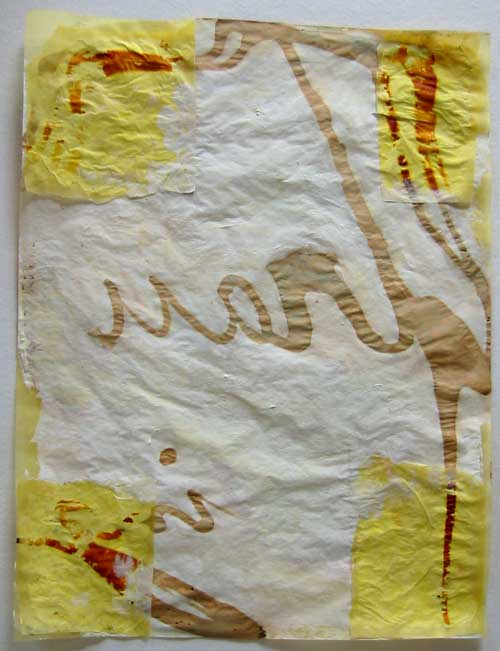

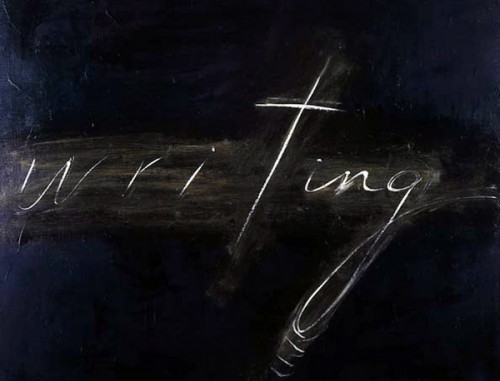

Mira Schor, August 1984. Gouache, dry pigment, medium on rice paper, 72 x 36 in.

The degree to which science fiction visions of a far future and dystopians visions of a near future have turned out to be true is quite astounding although, perhaps too influenced by conditions in the Soviet and the dreariness of post-War Britain, George Orwell was wrong in thinking that political intimidation and mind control in the future would only be achieved through fear and brute force though these are still frequent methods in dictatorships worldwide. But now it is more often achieved through toys. We use our communicating devices in a pretty close manner to the way they appeared in various versions of Star Trek and we are as hypnotized by our devices as the crew in the STNG episode The Game from October, 1991, where, spoiler alert, the hypnotizing game, basically played in your visual cortex through something like Google glasses, is actually a tactic by aliens of distracting and brainwashing the crew to allow for a take over of the Starship Enterprise and the whole Federation–on STNG it’s a race called the Ktarians, before they fully understood the people from planet Jobs. Plans are afoot to replicate meat, next thing you know, Soylent Green–there will be a fancy way of making it seem palatable as a reasonable solution to global warming or overpopulation, if you read the Wikipedia description of the plot of the movie Soylent Green, well, hello, today’s news. Today’s Times leads with an article on N.S.A. phone logs, as continued revelations of the degree to which all private communications are collected and monitored by governments and corporations challenge our illusions of privacy here in the US. I heard earlier this summer that cable boxes already have the capability of not just recording our choices of programming but they can see and hear us, they literally know when we get up and go to the bathroom.

When I think about the future, I think how the old and the new will continue to mix, but not necessarily in ways that will be easy to fathom. Already every new public bathroom is a challenge, as I try to figure out the mechanics of the particular faucet and the toilet–do you wave, do you get up, do you move the little lever up or down or sideways, and why is each different when for a century they were recognizably the same? I also think of the things that I have used in daily life for over 60 years which in the near future either will no longer exist or will have become luxury items: maybe in 2031 we will still have paper towels (invented in 1907), as an example of something I use everyday–in recent years struggling between awareness that they are part of a pattern of environmental havoc and the fact that they are just so damn useful, and hatred of the Koch Brothers notwithstanding–but they will be prohibitively expensive.

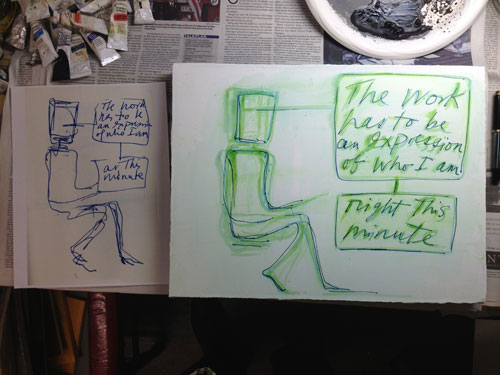

As an artist, as it is, many art supplies that form the core of my work are disappearing from the market–these include various inks, oil paint brushes, sizes of paper, types of sketchbooks, types of gesso, not to mention pure spirits of gum turpentine in containers one can easily open, and even my favorite brand of Stand Oil. These disappearances are due to corporate restructuring, new technologies, the elimination of niche and craft manufacturing, and to marketing to the lowest common denominator of customer, in this case amateurs or beginners who don’t know the difference between a generic product and a high quality product: if you have never held a tube of high quality cadmium red light paint in one hand and of a student grade brand of the pigment of the same name in the other, you don’t understand how little pigment is in the student grade. If the color red is not as you had dreamed it because there is actually no pigment in the paint, you think there is something wrong with painting, not the paint brand you are using. (see discussion on Facebook about such matters, from June 30).

Reading predictions of the future can make you wonder about what you work so hard to accomplish in the present. For example I put a great deal of effort and resources into trying to preserve my parents’ work and histories, as well as my own artwork, but if New York is going to be largely underwater in fifty to a hundred years, as some studies predict, so will its museums and libraries, so maybe I shouldn’t bother.

I am not a huge reader of science fiction and I don’t have enough of an understanding of the present to be a futurologist: in fact I have a hard time understanding how we got to the point we are now, where almost all cultural developments I thought were achievements for the common good, from civil rights to women’s rights to environmental controls, are being dramatically reversed. I know that change for bad as well as for good can be abrupt, or it can be insidious, as were the changes in the economy and social philosophy taking place from the seventies onward, that have created our Nineteen Eighty-Four, our Brave New World.

August 1, 2013

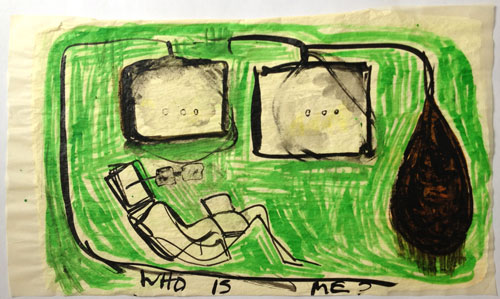

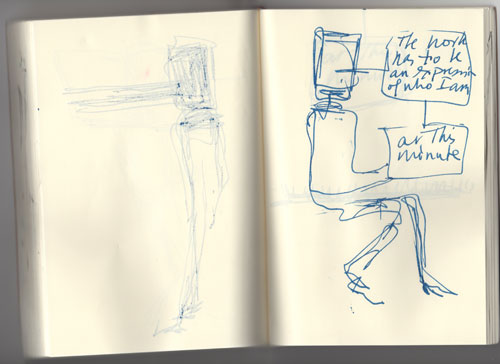

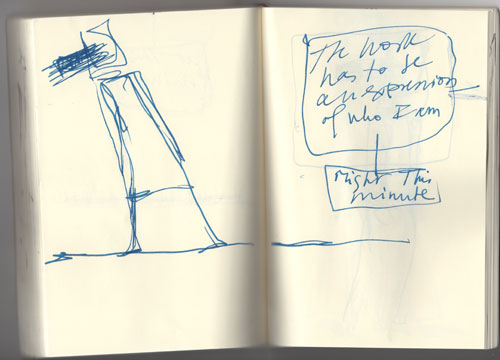

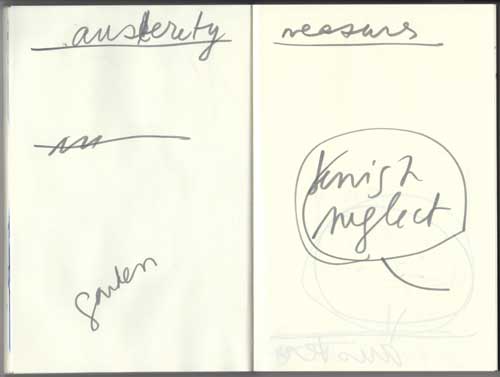

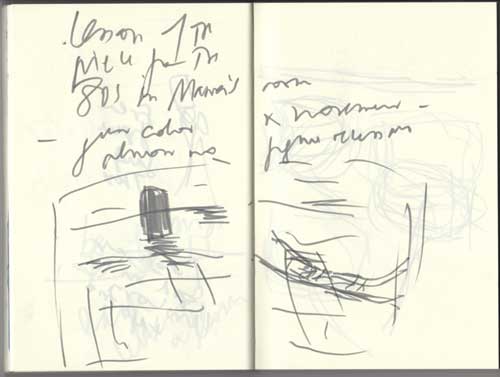

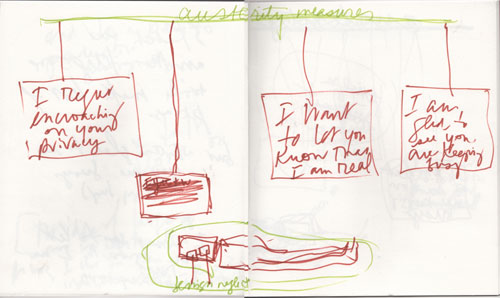

To be honest and true to the letter of the law of these posts of works done on a particular calendar day over a period of about forty years, this sketch is from yesterday afternoon, July 31, 2013. Most of the text is appropriated from scam/spam emails and annoying emails from people I know. 1984 to 2013, other things on my mind for my work than the beauty of place.

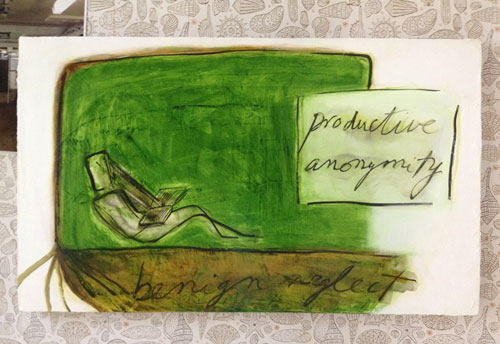

Mira Schor, Chatter, sketchbook, July 31, 2013. Ink on paper, 14 x 22 in.