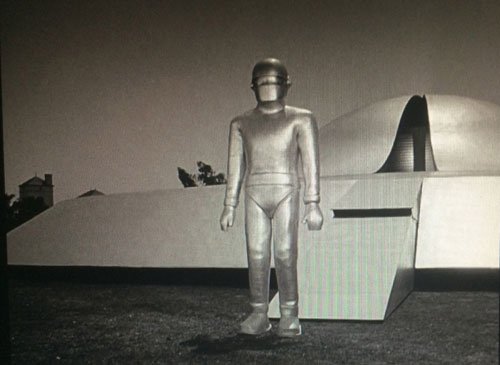

About halfway through the 1951 sci-fi film The Day the Earth Stood Still, all electricity, indeed all machine-run power on earth stops except for that which sustains the motion of planes in flight and life-saving institutions such as hospitals. It is a demonstration to humanity, and more specifically to all world leaders, of the power of an alliance of planets which has sent a representative to Earth in the form of a very distinguished-looking humanoid by the name of Klaatu, and an invincible 8 foot tall robot, Gort. Klaatu’s mission is to warn of the impending destruction of Earth, if humankind, newly endowed with nuclear weapons, threatens to extend its destructive proclivities beyond its own planet.

For an anxious half-hour, though the Earth does not actually stand still in its orbit, as suggested by the film’s title, everything that is considered “progress” and symbolizes the power of humankind–is disabled. Needless to say, all but the few earthlings who have had personal contact with Klaatu, react with fear and aggression rather than curiosity and awe. This cessation of power is Klaatu’s ingenious response to an Albert Einstein-like character’s challenge for a demonstration that will convince world leaders of the alien powers without inflicting any destruction.

When I was a teenager the gears of my mind jammed every time I heard the title of the Broadway musical, Stop the World–I Want to Get Off. It’s hard to reconstruct why this title confounded me. I could understand the stop the world part, not the get off part. Later, I would think, Stop the world, I want to get on, because I felt I was in a race where the other racers were halfway down the track before I’d tied my shoelaces (the art rat race). And now I think, Stop the world, I want to stay on.

The news this summer has been bad, bad, bad. There is no direction you can turn to for relief or optimism. I look to the Science Times and think, I guess it’s a good thing that MIT has developed “origami robots,” I bet the scientist and engineers working on that feel the world is going forward in a good way, and, granted, with the greatest of human optimism, Facebook friends post pictures of their ineffably confident newborn babies and grandchildren, but otherwise chaos, cruelty, and stupidity reign and the future often looks like a slow moving tsunami that turns out not to be that slow. If the earth with its inhabitants were someone’s child, it would be getting a time out right about now. There is a deep deep need for a moratorium, a bank holiday of global scope, a detox. It’s time for an intervention. We need a year of humanitarian ceasefire, or decades, and by ceasefire I mean not only of intractable sectarian battles and ancient hatreds, but also of global assaults on the land and on the fishes in the sea, of stupidity in leadership such as couldn’t even be imagined at the depths of the McCarthy era, when The Day the Earth Stood Still was made. As any individual who has suffered a personal loss or incurred an injury can attest, recovery takes much more time than is ever allowed and there are so many wounds that need to be healed around the world. Healing needs time, rebuilding needs time, learning needs time, time for constructive work, and time for rest.

There is no activity on earth today that could not benefit from time to lie fallow. The Earth may have to stand still to go forward.

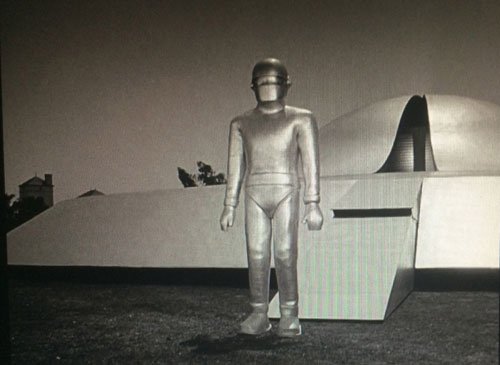

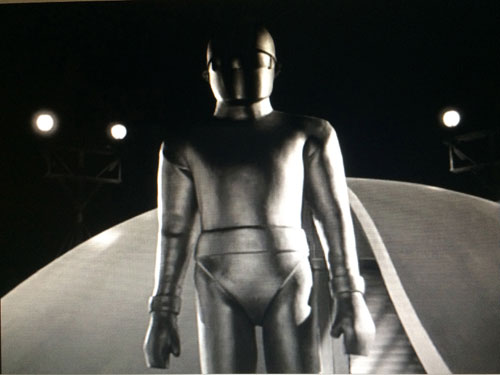

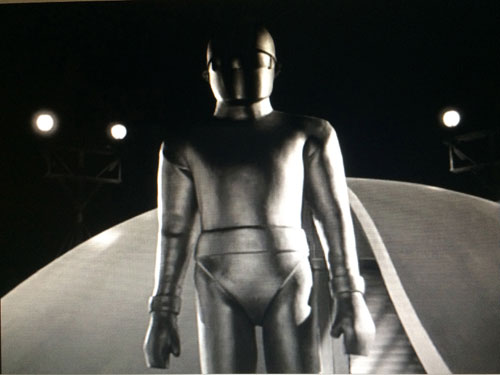

The Day the Earth Stood Still is a model of cinematic economy and an engagingly tight little amalgam of genres–film noir / sci-fi / political thriller. It’s not a monster movie like many other sci-fi horror films from the period, like The Thing, Them, Godzilla, although what sets the narrative in motion, like the others, is the development of the atom bomb. The word “monster” is uttered only once: as Klaatu, an extremely elegant and hypercivilized figure with a British accent (as played by British actor Michael Rennie) who for good measure has taken as his cover name the Jesus of Nazareth referent, “Mr. Carpenter,” from the dry cleaning slip he found in the beautifully fitting suit he stole to escape the authorities, walks down a street in Georgetown at night looking for a place to stay, he overhears a radio broadcast, “there’s no denying that there s a monster at large.” The irony is patent. The only monster at large is human fear and stupidity. Even the robot Gort is a sleek modernist creation, unlike a Golem made of base matter, he is imperviously metallic and, most of the time, absolutely immobile, though we are told his power knows no bounds.

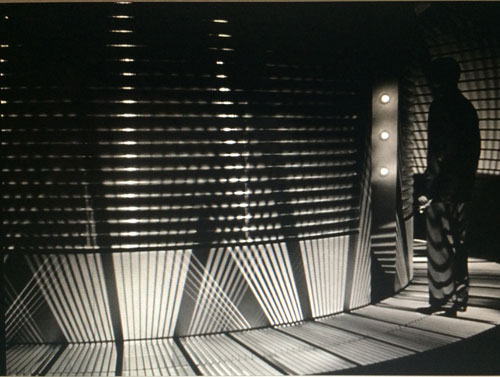

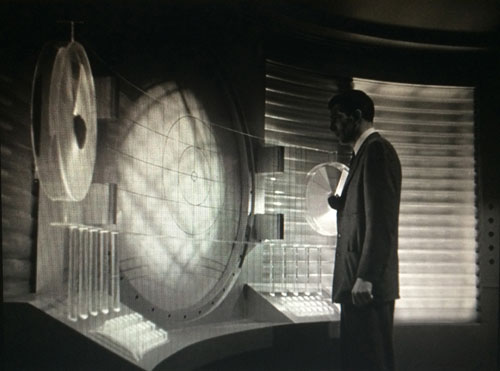

As for being a sci-fi movie, there is very little effort made to go beyond a business-like exposition of sci-fi tropes of the era: some Theramin-like sound effects, a glowing white flying saucer that appears above the Capitol dome in Washington D.C. before it lands in a park, near a triad of baseball fields and the Lincoln Memorial, a couple of vaporizations of armaments and later of a couple of men here and there. The exterior and interior of the space ship is basically Bucky Fuller’s Dymaxion House converted into a flying saucer.

And it’s not exactly a film noir, because the noir topos of woman as the source of corruption is reversed into a proto-feminist story: the heroine, “Helen Benson,” a war widow, played by Patricia Neal, a woman of modest means with a young son to support, immediately feels empathy with the creature spoken about on the radio, and later she resists the social imperative to marry her boyfriend when he reveals his craven ambition and self-regard in betraying Klaatu. Instead she risks her life to save humanity. Yet a lot of the action takes place at night, with a rich blackness punctuated only by street lights and neon signs of the city, recalling some of the tightly plotted, low-budget, location shooting, police films of the era, like The Naked City. The noir is not atmospheric and foggy, it is crisp, and for that all the more menacing.

The radio as a primary source of news is a recurrent theme of the film, a kind of communications hearth around which groups of people around the world gather. One of the charms of the film is the way that director Robert Wise makes especially effective use of what were even at the time long clichéd cinematic tropes and conventions of montage so that one can both step back and admire known methods of cutting used in a workmanlike fashion and still be thrilled and informed by them at the same time.

In particular, several times in the film, in order to advance the story and denote the global impact of the event, he creates quick montages where the same event is shown as experienced and reported simultaneously in different countries around the world, each country represented in a ten to twenty second vignette, with low budget sets, using stock footage: a village in France signaled by what is clearly a film stage set seemingly left over from the beginning of Casablanca and countless other Warner Brothers World War II movies, Moscow with a group of women in babushkas huddling together with the Kremlin in the background, American gathered around a radio at a gas station or in front of a radio store, people playing cards with the radio on in the background in the boarding house where Klaatu finds a room. Announcers from Calcutta to London, military personnel from bases in Florida to Britain–each nationality is telegraphed with a few easily recognizable signifiers. Television appears only peripherally, it is not yet the main medium, though there is one eerily predictive moment early in the movie where American TV news announcer Drew Pearson, as himself, looks into the camera and says, “the ship landed in Washington at 3:45 PM…Eastern Standard Time”–Walter Cronkite must have seen this movie.

Klaatu is an interesting figure: despite the Christ-like reference of his cover name, or perhaps in accordance with it, he is an unsentimental–and an unsentimentalized–figure, arrogant in the face of human stupidity. “I’m impatient with stupidity, my people have learned to live without it,” he tells an aide to the President of the United States–a curious wording which suggests that stupidity is something one feels the need of but can learn to do without. “I’m afraid my people haven’t,” replies the aide ruefully, since all he can come up are lame excuses about all the diplomatic impasses and impossibilities when Klaatu insists on speaking to all world leaders because he “will not speak to any one nation or group of nations.” He has come to “warn you that by threatening danger, your planet faces danger.” His “patience is wearing thin.”

When challenged to provide a demonstration of the alien power, he wonders, should he “take violent action, leveling New York City perhaps or sinking the Rock of Gibraltar?” He agrees to a demonstration that will be “dramatic but not destructive:” for a half-hour, the earth stands still, “electricity has been neutralized all over the world.” Again the montage, London’s Piccadilly Circus, New York’s Times Square, Moscow’s Red Square, factory turbines, trains, cars, dishwashers, milkshake mixers, electric cow milkers, and the elevator in which Klaatu reveals the plot to Helen, every thing stops. A half an hour later, everything starts again.

The earth is not receptive to Klaatu’s warning and his contempt for earthlings’ stupidity is not improved by his brief time on earth, during which he is shot twice and killed once. Only the kindness, curiosity, and faith of a boy, a woman, and one brilliant scientist may redeem the planet from immediate destruction.

Klaatu is resurrected by Gort. Before the ship leaves, he speaks to dignitaries assembled around the spaceship:

I am leaving soon and you will forgive me if I speak bluntly. The universe grows smaller everyday and the threat of aggression by any group anywhere can no longer be tolerated. Security for all or no one is secure. Now this does not mean giving up any freedom except freedom to act irresponsibly….We live in peace without arms or armies…free to pursue more profitable enterprises…I came here to give you these facts but if you threaten to extend your violence, this earth of yours will be reduced to a burned out cinder. Your choice is simple: join us and live in peace, or pursue your present course and face obliteration. The decision rests with you. We shall be waiting for your answer.

Judging from the news this summer, we are a lot closer to getting burnt to a cinder.

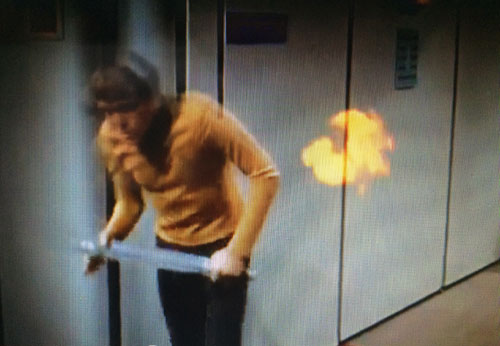

Another episode from popular culture that brackets the Cold War period offers what at first glance seems like a more idealistic voice from those years. It is another “day,” Day of the Dove, an episode from the original Star Trek series. The crew of the Enterprise receives a distress call from a human settlement on a distant planet. When they arrive, no sign of the settlement that contacted them remains. A group of Klingons appears, brought there by a similar call, from a Klingon settlement. They accuse each other of conspiracy and genocide and set upon each other, as a ball of multi-colored flashing lights flickers. It looks like the international radioactive hazard symbol set ablaze and in motion like spinning fire crackers. They accuse each other of dishonoring a peace agreement and of testing new weapons. As their anger grows, the ball of light becomes bigger and redder.

They all beam up to the Enterprise, unaware of the entity of flashing lights which follows them on board. Out of contact with Star Fleet, and propelled at warp 9 towards the edge of the galaxy, rage grows.

The premise of the plot is that this situation has been engineered by the flashing light, an entity which feeds on anger. It keeps the waring parties’ numbers balanced to ensure endless conflict, reviving injured crewmen if necessary, and it replaces their state of the art weaponry with swords and sabers to force the combatants backwards in the history of armament, from the disembodied impersonality of phasers to the savagery of hand to hand combat. It feeds them false memories of trauma and injustice to stoke the fires of hatred and vengeance: Chekov raves about how the Klingons murdered his brother, Piotr, and goes rogue to rape and kill any Klingon he can get his hands on. Upon hearing this, Sulu doesn’t understand, “he never had a brother, he’s an only child.” Kirk observes, “Now he wants revenge for a non-existent loss.”

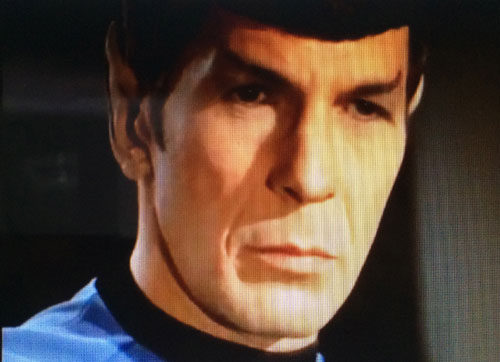

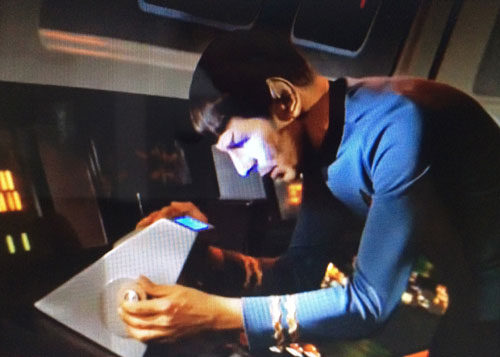

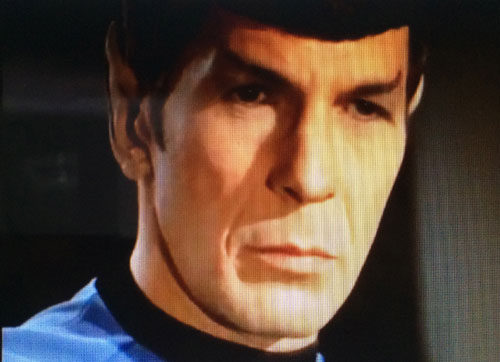

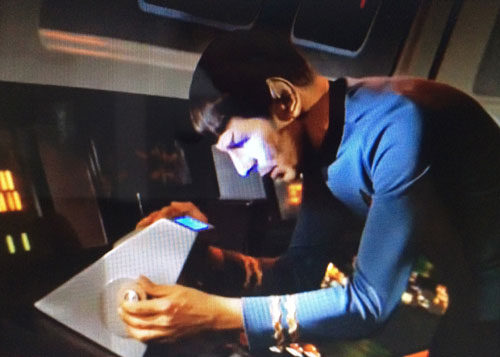

The crew of the Enterprise has the benefit of Mr. Spock’s scientific rationalism: a cool and unsentimentalizes figure much like Klaatu, down to the high cheek bones and to the arrogance of superior mental abilities, Spock is the first to see that there is something strange about the situation and, of course, find it “fascinating.” He realizes that the alien’s energy level increases with each battle, “it subsists on emotion,”and “it has created a catalyst to satisfy the need to promote the most violent mode of conflict.”

Once the Enterprise crew figures out what to do in order to prevent an eternity of senseless combat, they have to persuade the Klingons to participate in a course of action: stop feeding the beast, first by means of a temporary truce and ultimately by throwing down their weapons and laughing at the entity. As in The Day the Earth Stood Still, it is up to a woman, in the case Mara, the Klingon chief’s wife, to create the bridge between the groups and prevent destruction.

Star Trek was a left leaning show produced during the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights movement, with Women’s Liberation lurking on the horizon–the last show, Turnabout Intruder, is about a woman’s assaultive experiment in gender/body transfer because her love for Kirk is warped by her rage against gender inequity. In Day of the Dove racism is a major subject: the Enterprise crew understands that something is seriously amiss, that they are behaving irrationally and unlike themselves, when they begin to lob racist remarks at one another, notably when McCoy calls Spock a “half-breed:” later Spock confesses that for a moment he too had felt “the sting of racial bigotry…most distasteful,” he sniffs. Nevertheless it is telling that the script is unconsciously racist itself: the Klingons are portrayed as the more war-like and stupider race, more violent, less curious, compared to humans and Vulcans, and being a Klingon in those early shows is denoted very simply by greasy dark brown facial make up.

The first Star Trek series’ episodes were notoriously low-budget–more uses were found for bubble wrap than imagined in any philosophy!! It was television’s brand of modesty, similar to The Day The Earth Stood Still, but with the additional economy of time:the narrative had to fit into the 50 minute hour of network time, so each scene is instrumental and gets right to the point. There was a spareness to the message that had made so many of the episodes memorable.

Which film is closer to present day concerns? Though The Day the Earth Stood Still is a Cold War artifact, its paranoid uneasy spirit is closer to our time than Day of the Dove. In 1951, 6 years after WWII and Hiroshima and Nagasaki the message is, Stupid humans, stop before you are destroyed by your own stupidity. And humans don’t look too promising. But in Star Trek in 1968 at the end of a decade of cataclysm but also of liberation movements, relative prosperity, and of social and technological optimism, the humans and their enemies understand that their violence is being instigated by a force that feeds on rage and they are able to stop and laugh the entity out of power. But the truce is temporary. The entity is not destroyed, it just spins off into space, in search of the anger it needs to survive, which it has surely found here on earth.

In The Day the Earth Stood Still, alien forces have the power to destroy the Earth. They are ultimate judges with a police force of robots like Gort. In Day of the Dove, human (and other species’) inherent proclivity for stupidity and violence are incited by an alien force who enjoys the spectacle of war. As Spock says, “Those who sit back are the Gods.” In both cases, humans have the ability to step back and chose another path. The Star Trek episode leaves us with at least a temporarily instrumental decision to do so.

*

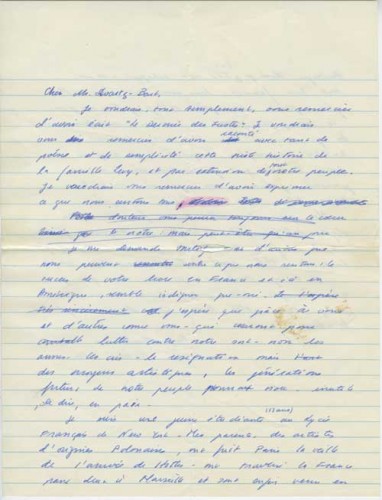

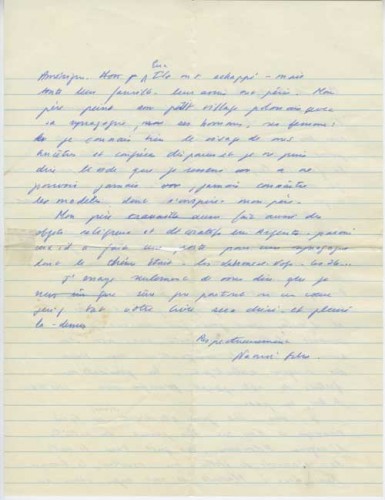

This summer, I reread a slim book, War and The Iliad, by Simone Weil and Rachel Bespaloff, two Jewish women living in France at the start of the Second World War who unbeknownst to each other each wrote an essay about the Iliad. Having reread the essays, I feel I must read them again and again, because they are mirror images that are nevertheless very different, like the two examples of popular culture I’ve mentioned here. As I read I thought about the obscene discrepancy between being able to read on a chaise lounge in a garden near the sea on a moist and breezy summer day and the circumstances suffered by so many victims of wars and cruel aggressions happening at the very same moment around the world as well as of relentless economic and social inequalities and injustices being perpetrated at home. This summer the world seems to spin the safe and the endangered closer together in a centrifugal motion towards disaster, although some of the safe may not see how they are as implicated and endangered as the rest of humanity. In her essay, “The Iliad, or the poem of force,” Weil quotes from the Iliad,

“She ordered her bright-haired maidens in the palace / To place on the fire a large tripod, preparing / A hot bath for Hector, returning from battle./ Foolish woman! Already he lay, far from hot baths,/ Slain by grey-eyed Athena, who guided Achilles’ arm.”

Far from hot baths he was indeed, poor man. And not he alone. Nearly all the Iliad takes place far from hot baths. Nearly all human life, then and now, takes place far from hot baths.

What power do the Gods have? In The Day The Earth Stood Still, the aliens from afar have the power to incinerate the earth, and both Klaatu and Gort have god-like qualities, Klaatu has both an Olympian impartiality, he doesn’t care what people on earth do to each other so long as they don’t do it to any other planet, and he has a Christian ability to spread the Word and to be resurrected, while Gort has the implacability of a graven idol. Bespaloff writes, in “The Comedy of the Gods,” a chapter of her essay “On The Iliad,” “Everything that happens has been caused by them, but they take no responsibility, whereas the epic heroes take total responsibility even for what they haven not caused.” The Trojan war is a form of spectacle and entertainment for them, “Condemned to a permanent security, they would die of boredom without intrigues and war.” Of Zeus, she writes, “There is nothing of the judge in this watcher-god. A demanding spectator, he accepts the law of tragedy that allows the best and the most noble to perish in order to renew the creativeness of life through sacrifice.” But Weil writes, “Force is as pitiless to the man who possesses it, or thinks he does, as it is to its victims, the second it crushes, the first it intoxicates. The truth is, nobody really possesses it,” even the Gods.

Weil writes, “The progress of the war in the Iliad is simply a continual game of seesaw. The victor of the moment feels himself invincible, even though, only a few hour before, he may have experienced defeat; he forgets to treat victory as a transitory thing.” As illustrated in The Day of the Dove, the alien force that feeds on rage must keep the waring parties evenly balanced: Weil points to the “extraordinary sense of equity” in the Iliad…”One is barely aware that the poet is a Greek and not a Trojan.” Bespaloff writes, “Sprung out of bitterness, the philosophy of the Iliad excludes resentment. It antedates the divorce between nature and existence.”

Weil describes why it is so hard to end combat:

Once the experience of war makes visible the possibility of death that lies locked up in each moment, our thoughts cannot travel from one day to the next without meeting death’s face….On each of those days the soul suffers violence. Regularly, every morning, the soul castrates itself of aspiration, for thought cannot journey through time without meeting death on the way. Thus war effaces all conceptions of purpose or goal, including even its own “war aims.” It effaces the very notion of war’s being brought to an end. To be outside a situation so violent as this is to find it inconceivable; to be inside it is to be unable to conceive its end. Consequently nobody does anything to bring this end about. In the presence of an armed enemy, what hand can relinquish its weapon!

Weil and Bespaloff both offers hints of what might be necessary for such a laying down of arms: compassion and an understanding of the balance of power. Weil writes, “The strong are, as a matter of fact, never absolutely strong nor are the weak absolutely weak, but neither is aware of this. They have in common a refusal to believe that they both belong to the same species.” Bespaloff makes an interesting comparison between Homer and Tolstoy’s understanding of “the fatality inherent in force,” but in one point she finds Tolstoy wanting:

In the spirit of equity, however, Homer infinitely surpasses Tolstoy. The Russian cannot restrain himself from belittling and disparaging the enemy of his people, from undressing, at it were before our eyes. The Greek does not humiliate either the victor or the vanquished. …Opponents can do each other justice in the fiercest moments of combat; for them, magnanimity has not been outlawed. All this changes if the criterion of a conflict of force is no longer force but spirit. When war is seen as the materialization of a duel between truth and error, reciprocal esteem becomes impossible. There can be no intermission in a contest that pits–as in the Bible–God against false gods, the Eternal against the idol.

The most famous line from The Day The Earth Stood Still is the sentence that Klaatu tells Helen she must say to Gort if something happens to him: “Klaatu barada nikto.” The meaning is never translated for us, but in context it seems to mean one or both of two things: “Klaatu needs to be resurrected,” or “Klaatu says, Don’t destroy the earth out of vengeance because I have been killed.” So at a time of calamity and conflict, destructiveness and in one of the worst periods I have lived through because of human stupidity and inability to accept any Others as equal or mirror images, or to act on scientific facts (Mr. Spock’s “fascinating”), I can just say, Klaatu barada nikto, Klaatu barada nikto.