I live on Lispenard Street just south of Canal Street in Lower Manhattan, fourteen blocks North of Ground Zero. From my corner I saw with my own eyes the second plane hit the South Tower of the World Trade Center and I lived downtown through the scary nights and the many rough months after September 11, and I am here to say that my whole street is a mosque. Several times a day, small groups of Muslim men, mainly African street vendors who peddle carvings or fake Vuitton bags and Rolex watches on Canal Street, pull out prayers mats, often just rolls of cardboard they store in the nooks and crannies of the buildings around, they take their shoes off in all weather, wash their feet with water from bottles, kneel towards the East and pray, fourteen blocks from Ground Zero, on ground they’ve spontaneously “hallowed.” And the only thing one can say, in the words of my Holocaust refugee Polish Jewish mother, is “Only in America.”

Or, at least, only in New York, where these outdoors rituals take place on the street surrounded by crowds of Chinese vendors, NYPD cops, business men, rich men’s children and their nannies, and busloads of women tourists from the American South who have come to buy those fake Vuitton bags from those vendors (nice Christian ladies who have no problem breaking New York City’s tax laws by buying fake label merchandise). Every day I pass these men praying on my street, across the street from my front door, and on corners throughout Lower Manhattan. It is an example of the religious freedom and tolerance that makes this country truly great.

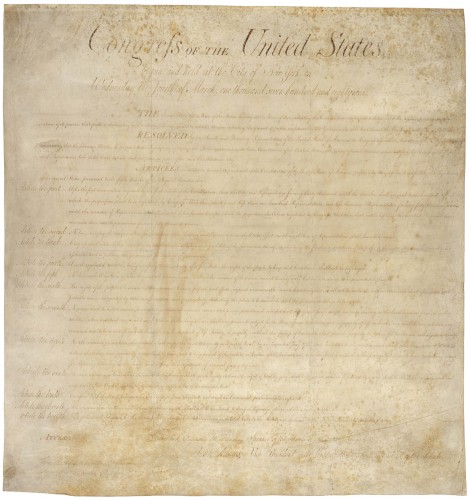

Politicians like President Obama should be wrapping themselves in the American Flag, waving the Constitution of the United States and the Bill of Rights and hollering about Freedom of Religion, the Mayflower, the Founding Fathers, Ellis Island, Land of the Free, at the top of their lungs, throwing every righteous trope in the rhetorical book of the myth of America at those who would destroy “the better angels of our nature,” not getting all wimpy and conciliatory in the face of people who pander hatred and bigotry and who are cynically manipulating Ground Zero Families and using the “hallowed ground” of Ground Zero as this week’s battering ram against America’s true greatness.

The first 10 Amendments to the Constitution, commonly known as the Bill of Rights, as important a document as the writing is faint

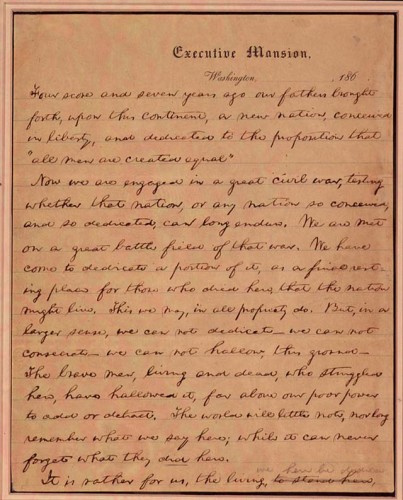

Abraham Lincoln's draft of The Gettysburg Address, delivered Thursday, November 19th, 1863, "in a larger sense, we can not dedicate, we can not consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract."