News flash: either the staff of Gagosian Gallery hasn’t been keeping up with the recent controversy over the removal of David Wojnarowicz’s video Fire in My Belly from the exhibition Hide/Seek at the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian, including the spectacle of another peaceful art activist being ejected and “banned for life” from the Smithsonian for quietly showing David Wojnarowicz’s video on his ipad [this story has since been amended to his being banned for 12 months only], or the Nostalgie de la Third Reich atmosphere of Anselm Kiefer’s show “Next Year in Jerusalem” had rubbed off on them when on December 18th they reacted to a few activists whose activism consisted of standing around in black T-shirts with “Next Year in Jerusalem” printed on them in English, Hebrew, and Arabic, taking pictures of themselves in front of the work, & quietly answering questions by to the harmlessly peaceful protest by having NYPD officers forcibly eject them from the gallery.

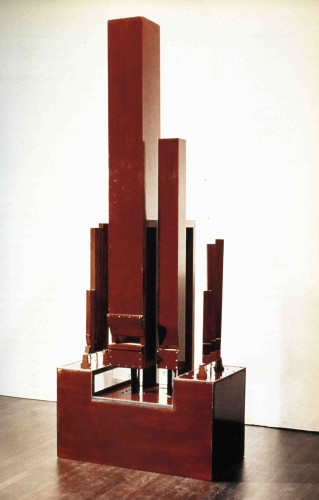

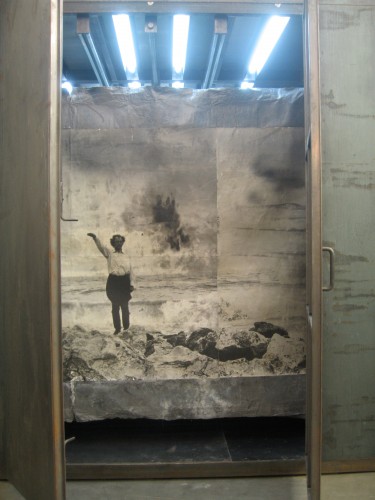

Protest at Gagosian Gallery, photo contained in an email by Laurie Arbeiter

I had wavered about whether I wanted to bother writing about the Kiefer show. The show closed last week and that would have been that until this morning when I read an email forwarded to me by artist Joyce Kozloff from one of the protesters, anti-war activist Laurie Arbeiter.

From her email:

In response to the title of the exhibition and the content of the work a small group of artists and activists decided to view the show wearing a shirt with the words Next Year In Jerusalem in the three languages Arabic, Hebrew and English. We spent about one to two hours looking at the exhibition, mainly individually, silently and respectfully with full consideration of others viewing the exhibition. We simply wore the words on our shirts and did not engage with anyone unless they struck up a conversation with us. A number of people asked some of us about the meaning of the message, gave positive feedback, showed interest, asked where they could get the shirts or occasionally questioned our political attitude toward Israel and Palestine. … We never had an incident, raised our voices, disrupted anyone, and were not approached by the multitudes of guards that were there. … We thought we were in an arena of ideas and that words on a t-shirt without any other provocation would be an acceptable method of free expression in response to Kiefer’s work. We were so very wrong.

After about one and a half hours, half of our group left and four of us remained to continue to view the show. … Suddenly, out of nowhere, two representatives from the gallery approached us. One of them asked who our leader was. It was an odd question and I responded that we had no leader. … She then said that she had to ask us to leave the gallery. … At that point, the gallery employee ordered the guards, the same ones that had observed us for close to two hours with no incident, to surround us and escort us out. I told her that there was no reason to have us removed. The gallery employee explained that they had received complaints about the words on our shirt, which were causing confusion, and therefore we would have to leave. We then decided to cover the language even though it was very disturbing to do so and we did this reluctantly, understanding the profound irony against the back-drop of the Kiefer exhibition which embodies a life’s work supposedly concerned with the horrors of state-sponsored repression, the brutality of occupation, racism, abuse of power, fascism and the consequences of forgetting history, not allowing for keen reflection in regard to current strains of unchecked power. I mentioned to the gallery employees that I thought we were in the realm of ideas inside the gallery space to which she replied that it was a private gallery in the business of selling art and that they wanted us to leave. On principle, something no longer that valued or defended in the public or private sector, we stayed, acting again in no way that could be deemed disruptive. The guards went back to their corners and we went back to our conversation. We thought that the incident was over. To all our shock, several minutes later the police arrived and completely disrupting the calm atmosphere in the gallery began to order us to leave and threatened us with arrest for trespassing.

Within minutes after the police arrived an incident unfolded that could only be described as brutal. Upon reflection, it was like a staged scene, depicting what happens when the very forces Kiefer warns us about go unchecked. The police came on very strong and at first directed their warning at us, overseen by the gallery personnel, who pointed us out to them. … The police officer was very rude and belligerent to her. All this unfolded rather quickly, within seconds and suddenly I saw him grab her forcefully, pinching the muscle of her arm as he began to drag her from the gallery. It was shocking as she was screaming that she was being hurt and yet he wouldn’t remove his grip. I heard her cry in pain all the way out as she was being removed to the entrance. …. She was badly bruised and needed medical attention and was taken to a hospital emergency room.

These are the facts of my experience as it unfolded. It was and still is traumatizing to recount and to attempt to grapple with all the implications of these events unfolding against the backdrop of the Anselm Kiefer exhibition. … Our peaceful engagement with the Kiefer exhibition was not a demonstration that day in the gallery but the gallery deserves now to be shown what a real demonstration looks like in response to what it did.

Incredibly, Renée Monrose, an artist who recently received a Masters in Divinity from the The Union Theological Seminary last spring and is now in the Seminary’s Master of Sacred Theology program, witnessed a similar incident at the gallery later the same day, December 18, and tried at some risk to intervene. It seems like Larry Gagosian’s minions are wearing brown shirts these days. They’ve lost all sense of proportion, common sense, and humanity. As Bradley Rubenstein aptly titled his critical review of the exhibition, “Achtung, Baby.”

From an email from Monrose:

I witnessed a very disturbing police incident tonight at Gagosian Gallery on W. 24th Street. It was about 5PM and a woman who was apparently being followed by guards–I don’t know why–suddenly turned on one and yelled, “Leave me alone! I just want to see the show.” I was about 10 feet away from her. She lost it and made a scene for a minute or so and then stormed out of the room. I thought she had left but when I went the reception area a few minutes later to get a catalog, she was down on the floor in the hallway, handcuffed and surrounded by at least 5 policemen. I protested and asked why in the world they need to handcuff and surround a 100lb woman who was obviously distraught (I don’t know that she was “disturbed” only that she was angry and, at that point, terrified.) They blew me off and told me to get away. I then went to the reception and complained to them. I was told by one of the young women “We have had other incidents” as if that explained the treatment of this women who was handcuffed on the floor about 20 feet away from her. The police then took the handcuffed woman into the vestibule near the front door, put her up against the wall and stood in a huddle around her. She was crying and shaking. Again, four or five of them were standing around her in a semi-circle. When I walked up to the police she recognized me from earlier and asked me to help her. I again protested and demanded to know why they were treating her this way. I was told, “She refused to leave.” … Eventually EMS came and strapped her to a gurney. She was put in the ambulance with 4 police officers standing in the doorway of the ambulance as if she were Son of Sam. When I asked an officer why they needed an army to deal with an emotionally upset women who was already handcuffed and strapped down, he told me “She might have boyfriends with guns in cars.” (this was after about 15 minutes-or more– of them having her on the floor or against the wall.) When I asked why, if they were concerned about men in cars with guns, they were all huddled around the back door of the ambulance. He said, “We have to protect the EMS guys.”!!! … The gallery was about to close and the only people on the street were the ones coming out of Gagosian. … I was the only one who confronted the police, although an elderly German man said to me as they were pulling out, “They were outrageous!” As the show inside was the Anselm Kiefer exhibit, the irony and scariness of the incident were impossible to ignore.

I filed a complaint online with the police but didn’t have any badge numbers. I haven’t received any confirmation.

I’ve never felt I needed to write about Anselm Kiefer’s work. His paintings always struck me as glum in terms of color and stolidly competent yet strangely inert in terms of composition. I found their hugeness and sheer weight oppressive physically and ideologically. If anything I found the fact that MoMA had to reinforce its walls for the 1988-89 exhibition Anselm Kiefer to support the weight of huge, often lead-covered canvases more significant than the paintings themselves.

My writing is propelled by my need to express views I hold but that I find are not being expressed elsewhere. So I didn’t need to write about Kiefer because he was so effectively critiqued by art historians such as Benjamin Buchloh, in the service of the privileging of Gerhardt Richter’s address of German history and of an overarching critique of Neo-Expressionist painting and painting itself (in the by now familiar ongoing counterpoint to his support of Richter):

On that level, the question of the possibility of the representation of German history is already infinitely more complicated in Richter’s work than in Kiefer’s since, unlike Kiefer, Richter questions even painting’s access t0 and capacity for representing historical experience). Secondly, mediation occurs at the level of painterly execution, since Kiefer’s work claims access to German Expressionist painting as the means of executing his own project of historical representation. Richter, on the other hand, emphasizes both the degree to which history, if it is accessible at all, is mediated by photographic images, and also how not just the construction of historical memory but its very conception are dependent on photographic representation. … (Buchloh, Art Since 1900, p.614).

Anselm Kiefer is only the most prominent of the German artists who have modeled themselves on concepts that Habermas has defined as “traditional identity.” In the course of their restoration of these concepts, these artists have produced a type of work…that can best be described as polit-kitsch. (Buchloh, “A Note on Gerhard Richter’s October 18, 1977,” October, Vol.48, Spring 1989, 100, n. 5)

But this recent show really bugged me, from the minute I walked through the gallery’s outer doors.

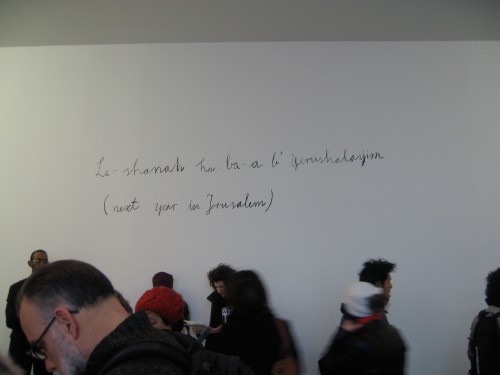

Above the entrance of a vast space occupied by a German were letters written in black script. In transliterated Hebrew and English, they spelled out “Next Year in Jerusalem,” the concluding line of the Passover Haggadah.

Next Year in Jerusalem? My hackles were officially raised even before I turned the corner and entered the occupied territory of Gagosian Gallery.

I still don’t really want to write about Kiefer, so here is just a précis. The installation reminded me of nothing so much as Bloomingdales’s cosmetics floor if its Christmas decorations had a Holocaust theme. The vast gallery space was packed to the gills and to the ceiling with huge lead-cased glass vitrines filled with burnt out WWII-era jet engines, Joseph Beuys-like oversized grey garments, a life-size wedding dress stabbed by shards of glass — a feminist art trope, long-since appropriated by male artists like Robert Gober — tree branches painted white which artist Joy Garnett described perfectly as being “worthy of the decor at an Anthropologie chain.” The installation also included a full-sized lead bunker containing among other things one of Kiefer’s early Nazi salute performance /photo-documentation works cited by some as examplary of the anti-monumentalism considered most suitably expressive of his post-war generation’s critique of Germany’s past, now set into a great big clunky monumental “anti-monument.” Through the vitrines one could see the crowds of other visitors to the gallery milling about while strangely obscured from view were characteristically enormous paintings so that these appeared almost as afterthoughts to the installation.

I thought about what title I’d give an essay about this show. “Arbeit Macht Gelt” seemed appropriate, in keeping with the association between the text at the entry of the show with the text on the metal entry gate to Auschwitz, “Arbeit Macht Frei,” and in keeping also with the price of the work. Overheard at the show: a youngish woman “gallerina” in mini-skirted business suit with high heels and information in hand about the work was shepherding an apparently potential buyer around. Fixing my eye away from them as if in deep contemplation of the work, I leaned into the conversation: gallerina to woman taping info into a purple Blackberry (looked as if they were talking about one of the vitrines): “$600,000.”

But maybe “Gelt Macht Arbeit” might be more correct. The work was a broadcast for how much it cost to produce it.

My friend Susan Bee had overheard the first part of their conversation, where the woman with Blackberry was apparently just learning about Kiefer and asked if he was Jewish — a reasonable inference from a show titled “Next Year in Jerusalem.”

It was in fact the nexus of aesthetic cliches in the work, its scale, size, & the obvious expense of production, shipping, and installation, with the arrogation of Judaism that I found outrageous. Big boring art, OK; incredibly expensive to produce art, whatever; huge prices, well, good work if you can get it, but the underlying positioning of Kiefer as the greatest Jewish artist of the Holocaust? That’s too much. (Though I do think it’s Mel Brooks funny that the gallery website for the exhibition has a glossary of terms including many related to Jewish religion and folklore: Gagosian Gallery as the source of a definition for Shekinah is pretty much like Madonna as a source for the Kabbalah). Thus my reasons for being incensed by the show were not exactly the same as those of the protesters, that is, Israel as a Jewish state itself engaged in political oppression, they were aesthetic and also based in my long-standing interest, rooted in my family experience (see my essay “Blurring Richter”), in how some post-War German artists (whether Richter on one side of an aesthetic/ideological divide or Kiefer on the other) somehow managed to finally win the war of eradication of Jewish subjectivity left unfinished by the Nazis.

This morning, in a kind of creepy serendipity, I noticed a link to color photographs of a Christmas celebration hosted by Adolf Hitler December 18, 1941, sixty-nine years ago to the day from the events at Gagosian. Seen in color we are so familiar with from our own experience, the Christmas decorations, albeit at Nuremberg rally scale, are more foreboding and the intense color shatters the distancing effect created by the many generations of “grey” representations that have shaped our image of the Second World War, from the accident of history that made black and white film more easily accessible and affordable than color well into the 1960s, to the reliance by Richter on grey as the emblematic color for an anti-ideological position, morally ambiguous yet also imbued by a kind of moral authenticity. In these color pictures, by klieg and candlelight, Hitler if anything looks more like his own Madame Tusseaud’s waxwork than he does in black and film still photography and film. The color both highlights a kind of artifice and reveals undercurrents of terror within the hearts of even Hitler’s most faithful soldiers.

Kiefer and Gagosian Gallery end up more Last Century in Berlin than Next Year in Jerusalem, while the color photographs of a Nazi Christmas Party in 1941 seem eerily like Today in the World.