Note: this piece does not endorse gun violence but the use of rhetoric in support of an idea, the idea of government as something that can and should help the people.

My mother used to say that, whenever George Herbert Walker Bush, Senior, “41,” would try to act tough and fight dirty, he looked to her like a sniveling wimpy little milquetoast mama’s boy whose mother says to him, “now you go back and you punch that bully in the nose.” Since the early days of Barack Obama’s presidency, a lot of people who think of themselves as intellectuals and pacifists are turning into that violent by proxy mother, increasingly inclined towards a kind of machismo, though sadly an impotent one, looking helplessly on as our country drives closer to the edge of the cliff (one of my actual recurring dreams is that I suddenly have to drive a car from the back seat because it turns out there’s no one at the wheel). The recent stirrings of dissent, despair and even some contempt for Obama, coming from his supporters (cf. recent columns by Michael Tomasky, Cornell West, Maureen Dowd, Judith Levine, and Frank Rich) have a tragic undercurrent, which is that the alternatives to Obama are so awful that even if we ever get past the dark political period that seems to await us, there may be no more of what was good about the American ideal left to salvage. As my mother also and presciently said to me one day, in about her 94th year, turning to me from watching the network news, “So, in America, soon it will be the corporations and the slaves.” (and, mind you, that was before “Citizens United” granted human being status to corporations). Meanwhile, we say “Man up” and “grow a pair.” Like bystanders in a classic movie fight scene, liberals and progressives have been hopping up and down helplessly punching the air and yelling out to the protagonist, “hit ’em with your left, kid.”

In any classic movie fight scene, you wait with increasing anticipation for the good guy to stop turning the other cheek, rise up, and sock that bully. The final fight scene in Howard Hawks’ 1948 Western film Red River is as good as any model for this classic wish-fulfillment fantasy. Montgomery Clift has rebelled against his tyrannical and wrong-headed adoptive father, John Wayne, by choosing an untested though ultimately successful path to get their cattle from their ranch in Texas to Abilene, Kansas, where the railroad to Eastern markets is and they can sell their stock for a good price. Once Clift has mutinied, taking the cattle and most of the crew with him on his pioneer journey, Wayne’s character pursues him relentlessly, vowing to kill him when he catches up with him. The movie is so entertaining that the underlying flaw in the basic plot doesn’t reveal itself until just after Clift finally strikes back, after taking a beating as Wayne matches verbal insult to punch by punch, “you’re soft, won’t anything make a man out of you.”

But, as the infuriated heroine realizes, Wayne never meant to kill Clift, because as anyone can see, they “love each other.” The Republicans don’t love President Obama, but that is not our problem. Our problem is that they don’t just hate him, they hate us, they hate children, women, sick people, old people, they have stated clearly that it is their goal that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall perish from this earth.

We’d like to see Obama get that “OK I’ve had it” glint in his eye and come out swinging, but Hawks, in effect, has pulled his punches, and the softness of this ending to what had seemed like a powerful Oedipal match, makes Red River less relevant to our current political dilemma than another Western movie: The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, (1962) John Ford‘s late, starkly simple, cinematically almost archaic yet profound meditation on the role of violence in creating the American democracy and on the nature of history itself.

For those who haven’t seen the movie, the action of the movie takes place in an extended flashback bracketed by scenes taking place in the “present,” (around 1910) and with the most crucial scene in the movie replayed as yet another flashback within the central flashback. The protagonists of the film are Senator Ransom “Ranse” Stoddard (played by James Stewart), who, when we first encounter him is the most distinguished politician in his state returning unexpectedly and mysteriously, with his wife Hallie (Vera Miles), apparently after many years, to Shinbone, the small town in the West where his legendary political career began. The central part of the plot takes place in the past, about thirty or forty years before, and centers around a few characters: Stoddard, a young lawyer come from the East to set up a law practice who, before his stagecoach even gets to town, is robbed and beaten, and his law books ripped up by Liberty Valance (played by Lee Marvin). In Shinbone, Stoddard is befriended by Hallie, then an illiterate waitress working for a kindly immigrant couple running the restaurant, by the local newspaper editor-publisher and town drunk Dutton Peabody, and, in an uneasy alliance, by Tom Doniphon (John Wayne), a local rancher and rival for Hallie’s affections. Doniphon is always accompanied by his black farmhand, Pompey (Woody Strode) in a kind of dignified adult version of the “Come on back to the raft ag’in, Huck Honey” classic former master/former slave homosocial partnership (I’m being snarky, but Strode gives a wonderful performance, and the sparely choreographed working and affective part of this relationship gives the movie a compelling sub-texture, as is so often the case in American mythologies).

The town is terrorized by Liberty Valance, a sociopathic, brutally clever, almost ironically self-aware robber, thug, and murderer operating as a tool for the unseen cattle barons who want to prevent statehood for this Western frontier territory so that they can retain free rein over the land and its resources. He has no respect for the written law although, significantly, he recognizes that the Eastern “dude” with the law books represents the most significant threat to his power. Valance lives by “the law of the West,” the gun. He stands between Shinbone and civilization. Something has to be done about Liberty Valance.

At first glance, and as has been noted by everyone who has written about it, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance is a strange movie in its formal qualities and its casting. It was shot in black and white long after even Ford himself, a master of black and white cinematography in his earlier great movies, including such black and white film masterpieces as Stagecoach, My Darling Clementine, and The Grapes of Wrath, had turned to color in films such as She Wore a Yellow Ribbon and The Searchers. And even the black and white, except for a few night scenes, is much less rich and velvety than in Ford’s earlier films. To the contrary, it’s bleached out and anti-aesthetic, like a dried-out scrap of bone in the desert. The movie was shot on the cheap, using the back lot set of a television Western program, so the West as a physical space whose empty vastness was once one of the principle protagonists of many Ford movies, notably in his spectacular usages of Monument Valley, is barely present as subject and the action takes place almost as a play on sets reduced to the bare minimum of what each signifies: the saloon, the newspaper office, the restaurant. The sets and props are both extremely accurate to the simplicity of the time–the dishwashing and cooking implements in the restaurant’s kitchen for example–but at the same time they harken back to the flimsy movie sets of the earliest silent Westerns, when the West already being mythified was only a decade or two in the past. Yet this reductiveness is a strength, as the simplicity of the sets has a strangely convincing verisimilitude, and the theatrical structure–scene, scene, scene–keeps you focused on the story.

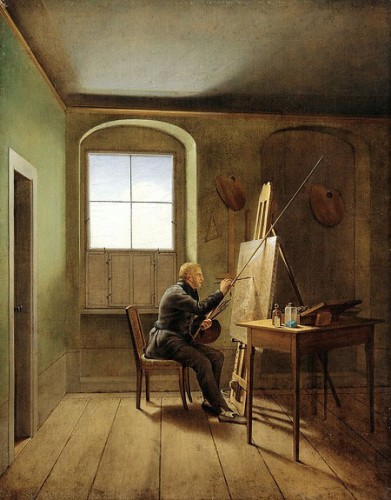

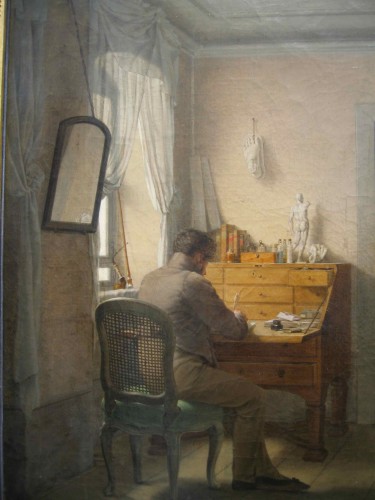

Ford knowingly relies on every trope and cliché of Western movies and of movies themselves, many of which he had helped create, from the stock cast of characters including stereotypes of major immigrant groups, from the Irish to the Scandinavian, to the classic flashback introduced by a puff of cigarette smoke. He relishes using our familiarity with these tropes to further his morality play, stripped to its essence by the deliberate plainness of the sets, the reduction in visual pleasure, the simplicity of the narrative. (One way of looking at this film is that it’s a good example the “old age style,” a phenomenon used to distinguish formal characteristic of late works by Titian, Rembrandt, or Cézanne, where the artist just wants to get to the heart of the matter and sloughs off all the fine finish he had needed to impress his audience in earlier years).

The quality of a morality play is exemplified and emphasized by the patent discordance between the ages of the two male stars and that of the characters they play. Characters in their early 20s are here played by actors in their 50s, and it shows. Their age cannot be masked by makeup. Whatever efforts made to do so only draw attention to the actors’ actual age. Yet this strange casting choice is extremely important to the greatness of the film.

First, because you can’t get swept up in their beauty or sexuality, you cannot be seduced and enter into a sutured Hollywood fantasy, so you are constantly returned to the meaning of the story.

Second, and most importantly, it’s precisely because each actor is who he is and brings to his part his own history as a representation of American character that they give the movie its unique gravitas. In fact in writing this I have been debating a formal question: do I refer to each character by his name in the movie, or by his name as actor. The idealism and incorruptibility of “Ransom Stoddard” is embedded in Stewart’s iconic role as the idealistic young Senator in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and other movies like You Can’t Take It With You, from his pre-WWII career, particularly his Frank Capra movies, yet also inflected with the toughness and desperation he brought to his own post-war Westerns such as The Naked Spur. In those movies his character becomes much more similar to many of Wayne’s characters: in Wayne’s many roles as the man of the West, he is the good guy but also often with an edge, some kind of an outlaw, beginning with the Ringo Kid in Stagecoach, a charming and good fellow but bent on revenge of his murdered brother or Ethan Edwards in The Searchers, another vengeful figure whose dogged pursuit of a kind of brutal justice is effective but founded on a bitter racism. And even though at the end of The Searchers he does not carry out the ultimate act of racial “cleansing” he has threatened throughout, he still cannot be contained in civil society. His character in Valance is named Tom Doniphon, but he is all of the characters Wayne had played to that moment, thus he is the construct “John Wayne,” a complex collaborative artwork created by Ford and Wayne himself over nearly 25 years. So these men, their faces and histories, are part of the meaning of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.

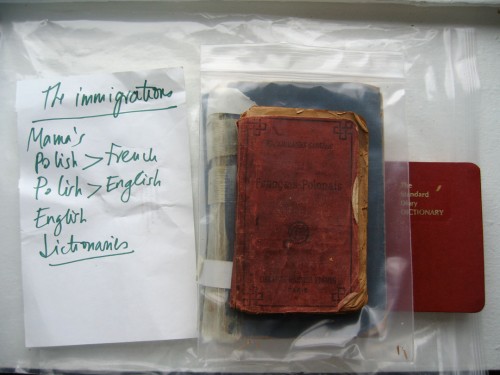

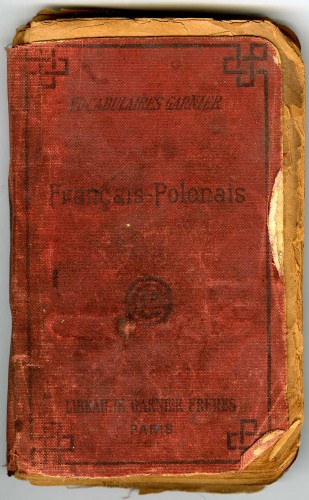

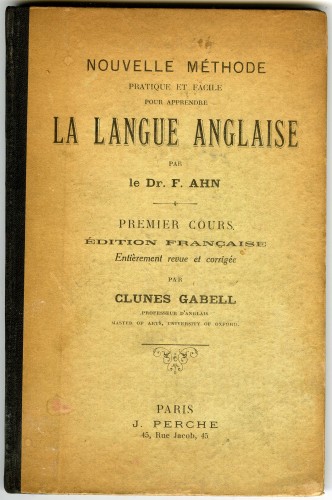

The history of John Ford’s movies is also part of the meaning. For instance, Valance’s first appearance is a fascinating contrast to Wayne’s legendary first appearance, almost a materialization, in Stagecoach: in that earlier Ford movie, the stagecoach, whose occupants the audience has been introduced to so that we are already invested in their voyage, speeds across the desert in daylight until it is brought to a sudden stop as, simultaneously, the camera suddenly swoops in to the indescribably open and surprised expression of John Wayne. I’ve watched this scene dozens of times, but the speed and complexity of camera shots defies my ability to describe technically what Ford is doing. I do know that my parents saw Stagecoach in Paris just at the beginning of the Second World War, and they thought it was marvelous, the whole sweep of it and I think too the basic good and open nature of Wayne’s character represented America to them, a place they would soon set out to reach, over a year and a half exodus across occupied France where they became the endangered travelers in the stagecoach, trying to get to Lordsburg.

In Valance, on the other hand, the stagecoach unceremoniously careens recklessly out of nowhere down a narrow road at night until it is brought to halt by a gang of masked men. “Stand and Deliver,” declares the gang’s leader, Valance. Everything that was thrilling, open, bright, optimistic in Ford’s earlier version of the west is dark, cramped, pessimistic in the later version, though I think the movies are necessary companions for a full understanding of the dream of America.

The movie’s anchor scenes are of the killing of Liberty Valance, seen twice, first as Stoddard experienced it, and later as it is replayed from the point of view of Wayne. This is not a Rashomon situation, this is not about the basic fungibility of truth. Here there is the first mise en scène (the “legend”) which you as the viewer experience essentially as it is experienced by Stewart, that is as reality from the point of view of a protagonist you trust. You are definitely the spectator watching something unfold on a stage before you, carefully and excruciatingly choreographed, to emphasize Stewart’s terror and his bravery as, already shot in the right arm, he reaches trembling for his gun with his left hand.

Then, later, there is the second mise en scène, (the truth), where the same exact events are re-shot from a greater distance, and a different angle, as experienced by Wayne. Just as there is ultimately no doubt of which version is true, this dual iteration of staging is precise, concise, it is even didactic, like a textbook of basic film staging, reverse shots, reverse angles, reshooting the same staging from a different place in the proscenium theater that we occupy. What in the first iteration was lived by Stewart, in the second becomes a spectacle in which Wayne and “Pompey,” as unseen spectators in the dark affect the outcome without being seen before they vanish into the night, having played their parts with physical economy and precision.

So what does The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance have to tell us about our current predicament? You have the skinny young lawyer from the “East”–Obama the law professor and community activist from Chicago up against John McCain, the rich guy from the West and the many thuggish representatives of the unseen cattle-barons (The Koch brothers, FOX News, et al). The nitty gritty of politics take up a big portion of the movie. There is a great scene in which the townsmen assemble in the saloon to chose a delegate to the statehood convention. The cattle barons who are against statehood are represented by Liberty Valance, who nominates himself as delegate to the convention even though he is not a resident of the town–Marvin’s line reading of Valance’s retort–“I live where I hang my hat”–is particularly wonderful. The cattle barons’ interests are also promoted by a Major Cassius Starbuckle, a grandstanding politician who with florid oratory vilifies Stoddard as a killer and puts up for nomination a fellow in a fancy white suit who gallops onto the stage on a white horse (Texas Governor Rick Perry, anyone?). The Starbuckle character is every political snake oil salesman, shill for the Man, and was already so familiar a type that at the time the movie was made this type had been already been satirized for years in Looney Tunes cartoons as “Foghorn Leghorn,” always getting lost in vain and aimless oratory. We know these clowns, we’re still surrounded by them, the Glenn Becks and all the others.

The crux and the complexity of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance is that “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance” actually didn’t shoot Liberty Valance but his distinguished political career is built on the public perception that he did. At first glance this seems like a perfect example of the political mendacity and inauthencity we’ve become all too cynical about and most critical analyses of the film focus on the line spoke by the journalist who having heard the whole story of what really happened, destroys his notes, “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” That has become the take-away quote from the movie.

Another common view is that “The hero doesn’t win; the winner isn’t heroic,” except for one thing: the movie’s crystal clear demonstration that, though his career is built on a “lie” or a “legend,” Ransom Stoddard is a courageous man, maybe even more courageous than the man who actually did do the shooting (or, more accurately, the effective shooting). It is the question of courage and the dilemma of how best to achieve justice that are more interesting to consider given the current political moment.

The man of words, the figure Dowd refers to as the “egghead,” (a misnomer for Stoddard–the definition of the egghead, a term used to describe Adlai Stevenson, the thinking man’s Democrat in the early 1950s, is the intellectual as pathologically indecisive–but Stoddard does decide), the representative of the law does give in to the need for the gun, even though the gun is old, he can’t shoot straight, he is alone, and he’s wearing an apron to the gun fight–indeed, significantly through much of the movie, we’ve seen him in this humiliatingly feminized (dis)guise: literally he is wearing an apron because he’s taken a job washing dishes at the restaurant. But he does stand up for his beliefs, he does risk his life, or is prepared to sacrifice it, because of his belief in the law.

There is a very important scene in the movie which shows us what Ransom Stoddard truly offers the country: in a shabby one-room schoolhouse he has welcomed a significantly diverse student body, Mexican children, girls, adults, even the black man Pompey is allowed to attend. Here, significantly, Stoddard wears a suit, the mantle of his future authority. And the subject beyond the a b c s, is democracy. “We’ve begun the school by studying about our country and how it is governed.” The Scandinavian restaurant owner continues, “It’s a Republic which is a state in which the people are the boss, that means us, and if the big shots in Washington don’t do what we want, by golly we don’t vote for them no more–anymore, anymore.”

Later, there are two key instances where Stoddard is also shown to be willing to walk away from a political career, first because he is disgusted that it would come to him because of a violent act, second when he discovers it would be based on a lie, and, third, when he tells the whole story to a journalist.

The man who did Shoot Liberty Valance may also be courageous but his motivation is basically apolitical, he did it because the woman he loves asked him to help, and his act is cold blooded, the recognition of a necessity, the solution, the radical social remedy to evil, as he himself acknowledges, it was “cold-blooded murder but I can live with it.” Yet he loses everything: by letting Stewart get the credit, he loses his girl to Stewart, and by helping create a civilized country based on law, he loses his individualistic identity. We know what happened to Stewart, his resume is repeated by various characters, Governor, Senator, Ambassador to Britain, Senator again, possible Vice-Presidential candidate. Wayne’s life in the years that passed between the central flashback and the “present” are blank. He lived out his life until he died. That’s it. And the country has becomes the United States of America, for better or worse–the film’s conclusion is pretty ambivalent about that.

Of course the polished politician we see at the beginning of the movie, in the frame taking place in the “present,” may well have made many compromises of these noble ideals of democracy in his noted career, no doubt smoothly negotiating in favor of the forces of “civilization,” symbolized by churches, schools, and the well-functioning industrial development symbolized by the railroad.

Stoddard does state that he wants to accomplish change without violence, he hates the violence everyone else espouses. But in the end he stand up with a gun. And in the end someone does shoot Liberty Valance. The movie doesn’t seriously question the fact that Valance must be eliminated for civilization to thrive. But one thing is for sure, it took two men to kill Liberty Valance, the man of law, “the egghead,” and the man of the West, the individualist who is basically good but is willing to use a gun if necessary because he doesn’t care about the consequences, he has no ambition to protect. But the point is, again, the man of law in the end is willing to sacrifice ambition to what he feels is the greater good, the elimination of evil and the success of a “good” government. It’s a stark moral, the ends did justify the means. It’s also an American story, revolutions including the Civil Rights movement succeeding through the actions and words of men of law and men of extreme speech and action, working together if sometimes oppositionally to achieve a goal that may be as tempered as the settling of the West but better than the alternative. While saying that the end does justify the means, the film acknowledges how much this is intellectually a contradictory and morally a deeply troubling position, and that the history of America is based on such demonic bargains.

Meanwhile we’re surrounded by Liberty Valances and the cattle barons they stand in for. For whatever the reasons armchair psychoanalysts can come up with, Obama just has not seemed to adapt to the territory he finds himself in, he’s a man always dressed for yesterday’s weather. His compulsive policy of conciliation with a vengeful and single-minded enemy have been a tragically unsuccessful strategy.

Or, he won’t fight back, and one can only conclude that he won’t fight back because he doesn’t believe in what the people who elected him want him to fight for. In his September 8th speech, he appeared to get tough, to man up. The next week it was announced that his plan for economic relief would be paid for by cuts to Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security. It is hard at this late date to take the “manned-up” rhetoric as anything but just words. We aren’t convinced he actually believes in the New Deal principles that made the American Century great and livable for a wide proportion of America. Meanwhile wealth disparity and the poverty rate in America increase shamefully while Americans, not given much of an alternative, turn to the quasi-fascist, anti-government, pro-super capitalism rhetoricians of the extreme right. They are our Liberty Valances. They are working for our cattle barons. Someone has to “kill them,” but with belief in ideas, not guns.

In The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, in one scene instead of a whole movie like High Noon, Ford economically telegraphs that Ransom Stoddard is alone against Liberty Valance, as two fellows just walk away from him, leaving him standing, in his apron. But yesterday a bunch of people tried to occupy Wall Street. Maybe that is what the people can and must do, not just stand behind Obama, but push him from behind and go ahead of him, until, if only for political advantage, he won’t just “man up,” but belief up. Stand and deliver. Somebody has to shoot Liberty Valance.