Just over a year ago I wrote In Memoriam: Rozsika Parker, Feminist Art Historian and activist to mark the death of the noted British feminist art historian and psychotherapist Rozsika Parker (December 27, 1945-November 5, 2010). A conference in honor of her work was held in London December 10, CELEBRATING ROZSIKA PARKER 1945 – 2010, A DAY SYMPOSIUM ON ART, FEMINISM, AND PSYCHOANALYSIS, convened by Griselda Pollock, Lisa Baraitser, Anthea Callen, Briony Fer, and Sigal Spigel, women noted for their expertise in art history and in psychoanalytic practice and theory, in keeping with Parker’s important contributions to both fields: indeed the themes of the panels cover the range of Parker’s interests: “Art Writing & History,” “Femininity & Cloth,” Between Art & Psychoanalysis,” “Maternal Studies,” “Body Dysmorphia”–all of these topics of continued central relevance to women artists and feminist practice. [update: 300 people tried to register for the conference which had to be moved to a larger venue to accommodate the numbers of young and old from the art and the psychoanalytical communities who came to spend the day. A podcast of the entire Conference is available here.]

In honor of this conference, I would like to reprise part of my original post, which was quite short, and then publish for the first time an extraordinary correspondence that followed over the past year, between me and Griselda Pollock. I hasten to say it is extraordinary entirely due to the quality and interest of Pollock’s writing and, in my own mind, due to my astonishment to be communicating in any way with Pollock, a brilliant art historian whose work influenced me so much at a crucial time in my personal development within one of the most significant moments in the history of feminist art.

As a final introductory comment, the epistolary form can be a difficult one to read due to the episodic stop and go pacing imposed by the time frame of an exchange of letters, as well as the formal niceties of letter writing, all the flourishes that frame the heart of the narrative at hand, though when the first major epistolary form novels began to appear in the 16th century one can well imagine how much they would have appealed to people for whom communication by letter was a more extraordinary event than we might understand now as we are buried under our crowded email inboxes. Yet perhaps just now, when emails, text messages, with their presentation in thought balloon form on the iPhone for example, and Facebook comment threads dominate our communicative life, a return to an epistolary format may be the perfect format for a feminist conversation, given that the epistolary novel has a notably feminist history, with Aphra Behn, Jane Austen, and Mary Shelley using the form.

November 22nd, upon hearing of the death of Rozsika Parker, I wrote here on A Year of Positive Thinking:

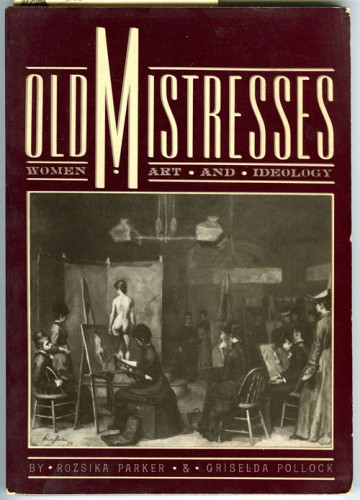

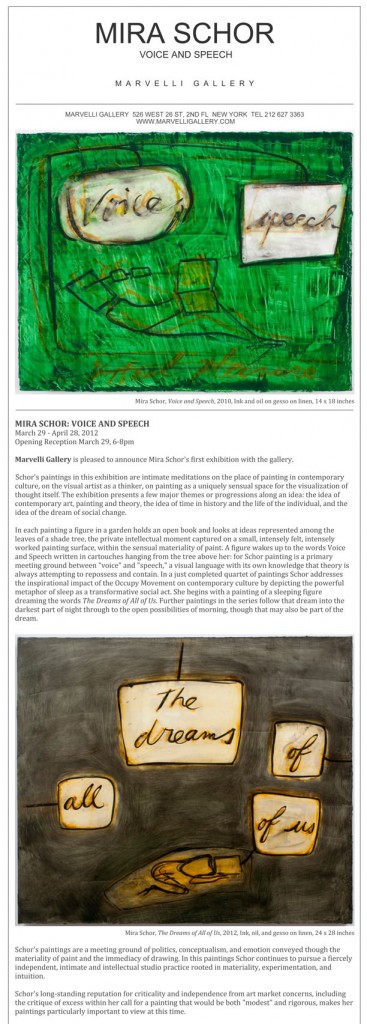

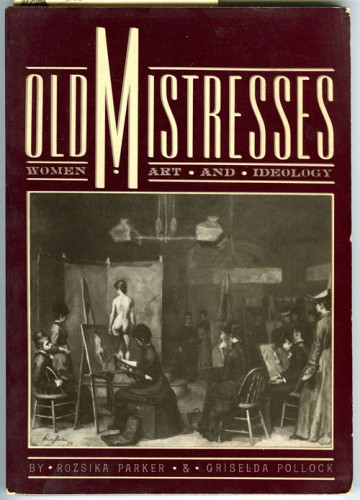

I consider Old Mistresses: Women, Art and Ideology, which Parker and Pollock co-authored, one of the most important books of feminist art theory and history that I ever read: Parker and Pollock examined how art history as a discipline had misogyny at its core, almost as one of its foundational purposes, with all its terms of value strongly gendered to condemn anything that smacked of the so-called feminine, although of course behind the naturalized frame of universalist neutrality. Their second collaboration, Framing Feminism: Art and the Women’s Movement 1970-1985 was and is a great source of information about the feminist art movement in Britain, which sometimes got overwhelmed by the American Women’s Liberation Movement’s belief in its own unique importance. Parker’s The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine is also a very influential and still relevant book, considering how much we now may take for granted that knitting or embroidering or weaving are acceptable media for high art, instead of being seen as crafts or as the hobby of well brought up girls or domestic servants.

Parker was a bit of a mysterious figure for all of us in the United States who admired these books because Griselda Pollock was the public figure of the two in the context of the art world and academia, speaking at many art history symposia here in the US, while Parker continued her feminist activism working as a psychoanalytic psychotherapist in Britain. Because it has been possible to follow the development of Pollock’s feminist ideology and aesthetic views in the books she wrote without Parker, I always have been curious about Parker’s role and voice in their collaboration and have tried to intuit it in the way one measures a black star, almost by negation, by what was not Griselda Pollock. I formed an image of a fierce feminism tempered by a compassionate focus on the work and the cultural issues affecting women, in life and in history, rather than the approach which won out in the 1980s, one that negated the “theoretical” existence of the (biologically determined) category “Woman” in favor of an interest in (socially constructed and non-biology specific) gender.

Sadly Old Mistresses and Framing Feminism have long been out of print. I hope that they can be re-issued because the passion and clarity and sheer historical data in these books would be of great interest to young women artists now.

Last February 2011 there were a number of panels related to feminism and art at the College Art Association Annual Conference in New York City, including “Feminism,” a panel co-chaired by Griselda Pollock and Norma Broude, held on February 9 at the Hilton Hotel, as well as “The Feminist Art Project: A Day of Panels” held at the Museum of Arts and Design, which included “The Problem of Feminist Form: A Talk by Aruna d’Souza” followed by a response from Connie Butler, The Robert Lehman Foundation Chief Curator of Drawings, MoMA. [As an aside, but one of general significance, at all of these panels at the main CAA conference at the Hilton Hotel and the Day of Panels at the Museum of Arts and Design, the attendance was huge: at the Museum, New York city fire laws were massively flouted, as hundreds of women were jammed together with their bulky winter coats and book-filled tote bags, crowding even the aisles and standing up along any wall surface available. The high level of interest was a bracing indicator of the continued and now renewed interest in feminism and art]

I had wondered if Griselda Pollock was aware of my blog post about Rozsika Parker but didn’t get a chance to talk to her either day. But February 10 after the Feminist Art Project “Day of Panels,” I received the following email from her, which I reproduce with her permission, followed by two more emails. I have added some links within the letters for background information and edited slightly the last letter because, not having Griselda’s permission to publish this last communication, I feel it is appropriate to publish only information I can be fairly certain she would not mind being made public.

Dear Mira,

I read with interest your brief report on the sad death of Rosie Parker last November. It was so shocking to us all that she could be snatched away so very young. But you have already experienced that grief through the loss of your sister. I appreciated your comments a a great deal as I wanted to affirm that Rosie was the original and powerful force in creating a feminist art writing shall we call it in Britain. She began alone writing her reviews for Spare Rib making it up as she went along. I keep thinking back now to what it was she gave me and what she enabled us to do in writing Old Mistresses. Collaboration is such a remarkable experience as neither party can claim authorship for what only happens when two people openly explore together, bringing their differences into creative play and each discovering their special resources and abilities only in the safety of an often hilarious as well as tough experience of pushing back the very limits of patriarchal authority which imposes such shame and fear on our minds as much as on our bodies. In your blog you rightly captured what it was that Rosie gave us and me in terms of making me a feminist writer on art: that things mattered deeply and seriously and that art touches on things that matter to us as we live them. That was what saved me from a bloodless and remote art history which i still cannot inhabit. But I wanted to correct one thing if I may: the shift from the engaged and passionate feminism that matters to real lives and real embodied people into the social construction of gender of the 1980s is both true and unfair. True I think in American academe in which intellectual women could not break through the internal shame police and made themselves respectable through a kind of intellectual transvestitism which prefers the social construction of gender because they then never have to deal with the messier aspects of our compromised and ambivalent bodies and sexualities. I began in the 1990s to engage with the work of Bracha Ettinger sharing with Rosie the continuing fascination with a feminist reworking of psychoanalysis – she went into it as a practice, I into its metapsychological domain. I remain interested in what we do not yet know about the realm of actual femininities and women’s lives and bodies and minds and what the more theoretically suggested notion of the feminine as a resource for non phallic thought, art and being might be. It is almost impossible to speak this in public without being booed off the stage or treated indulgently as a mad and embarrassing woman. I am not sure that we share similar positions on ‘woman’ or women; but I know that you too have battled against a kind of intellectual disowning of the feminine/the female, women. Ettinger is theoretically extremely difficult and arcane coming through what she has to say via Lacan and those whose works provide her with a means to insert a radical feminist rethinking of the meaning of the feminine. It is difficult to bridge the realms of everyday experience and the esoteric languages of philosophical analysis and certainly psychoanalytical theory. I know I do not succeed and people find my texts difficult and even excluding as they are written from within a realm of theoretical work few inhabit. I try to maintain some kind of deeper responsibility to bridge the realms or art and theory where important work is being done and the ordinary readers not able to spend a lifetime entering into their specialist ways of thinking and writing. I have functioned as an interpreter for Matrixial theory but I constantly find the American art historians blocking me with their discomfort with any discourse that assumes that there might be meaning in being a woman, however that has come about, or as I think Ettinger is saying that’ the feminine’ as she conceptualises it as a primordial gift of the ethical ability to share with an unknown other, to co-emerge into a coaffecting humanity.

I just wanted to respond to your very insightful blog about Rosie’s feminism> Her last book was about body dysmorphia and the agony caused by this dislocation of person and body. She taught me so much to engage with what really matters and that is about suffering, pain and the strange ways we have of negotiating both. She wanted to make things better through her work and her writing, through exploring difficult issues of love and hate and reflecting upon how she fostered the emergence of feminist art writing and thinking and shaped me as a feminist thinker, I go back to that. Yet I want to find a way not to be pigeon-holed as a theoretical Brit, a social constructionist. I never understood gender theory anyway since I was always in the psychoanalytical camp of exploring subjectivity and sexual difference. At the MoMA Feminist Futures it was Linda Nochlin and Anne Wagner who disowned by daring to say that the feminine has something vital to say to our worlds, futures and us.

Perhaps we share the fate of being not the mainstream of whatever has become hegemonic feminism: but to me it is not feminism at all. Feminism is about constantly questioning ourselves and daring to stay with what we find most difficult and uncomfortable long enough to work it through: no policing of correct thinking or orthodox positions. This is one of the vices I see in US academe: I am constantly told that what I am still thinking through is over, old hat, out of date. yet we hardly started on this vast project.

I am organizing a commemorative conference in London on 7 April for Rosie and I would like to reference your blog if I may as a way into really remembering and recognizing her groundedness in what matters for women and that art matters and art that is not about what matters matters very little.

Excuse this long screed. Yrs with best wishes, Griselda

Anyone who has ever admired someone from afar will understand the degree of my astonishment at this letter. It took me a few days to answer, writing to her on February 14:

On 14 Feb 2011, I wrote:

Dear Griselda:

Thank you for your touching and quite amazing email. First of all and above all I am so glad that you found my piece on your friend Rosie, and I’m honored that you would take notice of my really very humble attempt to mark her passing. I was in the audience for your introduction of your part of the panel on Friday and was very moved by your dedication of the panel to her and, sitting next to my friend and frequent collaborator Susan Bee, I felt very keenly the importance of a friend with whom you not only share experience and intellectual discovery but also with whom you create something in collaboration.

Upon reading your email to me I returned to my brief text to figure out why you should feel in any way that you would need to defend to me your position in the 80s on some of the theoretical and political ideas about gender and feminism that were, it is true, extremely divisive and occasionally maddening. So I just want to say how important your writings have been to my second education in feminism, in the 80s, when I had to sink or swim in a new theoretical situation quite different to my first in the early 70s.

It was a very contentious polemical time –once the 80s were over I sometimes referred to them as the decade from hell but on the other hand it was an incredibly interesting time — the disagreements were vicious and with genuine real life consequences (jobs and shows or not depending on what side you were seen to be on) but at least the arguments were over ideas, not like now when the market often dominates or subsumes discourse!!! I did feel that I ended up on what was perceived as the wrong end of the argument, or rather, that I was perceived as being on what was considered the wrong side, it always bugged me that I was consigned to the second class of “essentialist” — a bugaboo my sister and I both struggled with, although in my case the problem was compounded by my being a painter and one who did seem to work with difference (not sure which was worse, since painting, as I came to understand, was itself seen as essentialist).

As I think I can see from your comments, and as I experience myself, the divisions continue, somewhat the same though masked by new terms and conditions, with all the possibilities for (and exploitations of) misunderstandings that Sharon and Miwon seemed to underline yesterday. [I arrived at the very tail end of Connie’s and Aruna’s conversation, due to total stoppage of several subway lines because of what I later learned was the tail end of a murder spree, so I wasn’t clear on the issues you addressed in your response from the audience].

Griselda, I don’t know if you read my piece on Rozsika on The Huffington Post or on my blog A Year of Positive Thinking. I cross-posted the same piece since each site reaches a very different audience.

I designed my blog without a comments section, in part because I think they are unsightly and also because they are often too vicious. But I wonder whether you would consider letting me publish your email on my blog along with information about and a link to the commemorative conference you are planning for April–edited as you would wish, but I hope you would not feel the need to edit it too much because it is so insightful & touching about the nature of collaboration and so interesting as to past and present debates over gender and the feminine, and, as always, brilliantly written even as an email. It is really quite an extraordinary document and I continue to be astounded to have it addressed to me. On the blog I would recall my previous post on Rozsika (don’t feel I can call her Rosie but will think of her as such) with a link, would present your email as an extraordinary response, and give some information on the conference on her with a link to it if there is one. Do let me know if you would consider this. I hope you will.

And thank you for remembering my sister. That means a great deal to me.

All the best,

Mira

I didn’t hear back from Griselda for several months, until September 1, 2011:

Dear Mira,

I am so sorry for the long silence in reply to your email. Many things got int the way of our organizing a conference about Rosie. At last we have got this planned for 10 December 2011 in London. Details are below. I really like the idea of including my reply on your blog to open this all up a bit. I have no money for this event at all. But I wondered if we could circulate your piece on Rosie in the event or include it in some form, for instance you reading it – a digital recording or even a dvd recording as it would really add to the debate so much to have some transatlantic feminists involved.

I wonder what you think or we could read it out with a painting by you on the screen.

There are so many issues raised in your reply as well – notably about painting. What irritated me at the CAA event […]’s exploration of the question can painting be feminist as if this had never really been raised. It was a big issue with the usual misunderstandings in the later 1980s and early 1990s in Britain and Hilary Robinson wrote powerfully about women and painting as did my beloved friend Judith Mastai in Canada. Katy Deepwell was involved as was Rebecca Fortnun. I find myself now writing about painting amongst the many other practices and I felt once again the typecasting of British feminism and the fixing of boundaries and camps at the CAA – instead an openness to constantly revisiting the very varied landscapes of feminist thought and practice and building on bodies of debate.

The good news is the Old Mistresses will be reprinted in a new edition with a new preface sometime next year so that Rosie’s words and inspiration will be back with us again.

[…]

all the very best Griselda

My thanks to Griselda Pollock for her permission to reproduce this correspondence and my best wishes to all the participants of tomorrow conference in London.