There are lots of surprises in life:

Best wishes to my readers for a surprisingly Positive and Happy New Year!

& Look forward to some new posts in a new Year of Positive Thinking

Warm wishes,

Mira Schor

Mira Schor, drawing, 2009

There are lots of surprises in life:

Best wishes to my readers for a surprisingly Positive and Happy New Year!

& Look forward to some new posts in a new Year of Positive Thinking

Warm wishes,

Mira Schor

Mira Schor, drawing, 2009

During his excellent and self-confessedly pessimistic lecture at yesterday’s 2012 Creative Time Summit, held at the NYU Skirball Center for the Performing Arts, Slavoj Žižek urged the audience to see The Act of Killing, a recent documentary about atrocities committed during the 1965 anti-communist purge in Indonesia, and how some of the men responsible for the killing, imprisonment, and torture of perhaps as many as two and half million people (the figure I think given by Žižek) have not only never been prosecuted for war crimes or crimes against humanity, but are in fact celebrated and successful public figures. In a telling example from the film, as related by Žižek, some of the men are seen appearing on a talk show in which they openly boast about what they did to a young woman moderator who asks one of them, “When you had to torture the prisoners what approaches did you take?” He relates in detail how they figured out the best way to torture someone was by raping his female relatives in front of him, going into great detail on the most effective methods they devised to restrain, torture, and rape these women. The young lady moderator then says, “Amazing, let’s give Mr. (Anwar?) a round of applause.”

“Amazing,” an obscenity! However this anecdote was also amusing–squeeze some lemon on that word and salt it as well, of course–because the Creative Time Summit’s first day was marked by a relentless positivism embodied in its chosen style of presentation, a style derived from the equally relentlessly positivistic and corporatized TED Talks: in this format speakers are expected to be able to condense their work into a short and inspiring talk preferably not speaking from any notes and delivered through a wireless mike so that you can move freely and energetically around the stage. The word “amazing” was used liberally, notably by the organizers. Many of the speakers were indeed AMAZING but it is a crucial semiotic point that this style and format, enabled and dictated by the available technology, comes to the university and art world from the corporate world, in the Steve Jobs super salesmanship genre, thus they carry political DNA from these sources while other methods of presentation and thus of knowledge and political valence are suppressed. It makes one quake in one’s boots to think about Derrida, Foucault, or Lacan, under the Darwinian imperative to adapt, learning how to package their message in such a manner though maybe, clever fellows all, they too would have gotten with the program.

So the current cultural imperative is that you have to speak within the corporate salespitch format about some “amazing” thing you have done to prove that the world can be made a better place, unlike Žižek who introduced his talk by saying “You won’t get good news from me.”

Creative Time Director Nato Thompson cast himself in the part of Jimmy Fallon or perhaps a rather more 1960s style of exuberant game show host, and the audience was relentlessly encouraged to use social media and tweet the hell out of the event, which was being livestreamed and followed on Twitter, in fact after two of the short breaks in the proceedings a young woman (wirelessly miked of course) came out to read some of the tweets, which apparently were mostly commentary on what Nato was wearing. Only one fellow from Armenia was quoted as Tweeting that the conference was taking place and was being live-streamed. The AMAZINGness of instant interconnectedness was somehow muted for me since though a fairly indefatigable Facebooker, as so often happens at events that cruise on their technological sophistication, in the auditorium my iPhone could not get onto any of the so called free wi-fi networks labelled NYU this or that, my 3G connection was crappy, and my battery began to run low: the very elegant new auditorium should really have electrical outlets next to every seat, even the Peter Pan, Bolt, and other bus lines offers better wi-fi and plugs to their patrons these days. Why not just acknowledge that everyone these days is paying at least 50% attention to their iPhones while they are studying or teaching, working, walking, mothering, or at the theater, since doing everything private in public, thereby losing the true meaning of the public realm, was one of Žižek’s primary themes, aborted by the walk-off drumming that people started booing>OK some people are bores, time has to be controlled when there are multiple speakers, but this time around Žižek had promised us a semi-positive ending, which we never really got, and maybe that’s really the whole point, despite the predominance of the word AMAZING used by many of the presenters, not the artists I hasten to add, but by the Creative Time team.

The tone of the affair and the style of presentation was in significant contradistinction to a numbers of important presentations and events. First and let’s get it out of the way, two presenters, Hip hop artist Rebel Diaz and Cairo-based art collective Mosireen, had pulled out of the event at the last minute to protest that an Israeli organization was listed as one of the affiliated supporters of the event. The audience listened to reports and some commentary from presenters about these cancellations mostly in a silence that I could not possibly interpret other than my own reasons for it–a silence I must maintain because it is such a painful subject in which political realism of one kind, Israeli policies towards the Palestinians that I along with many Israelis find hard to countenance, meets political realism of another kind, which is the much more complex political history of the area and the real threats to Israel that cannot be denied, meets political realism of yet another kind, which is my own preternaturally calibrated sensitivity to any burgeoning under-any-other- name of antisemitism, meets political realism of yet another kind, which is that peer pressure is enormous to agree with the boycott, as yesterday, among many, artist Michael Rakowitz began his presentation by saying, “I’m a Jew, from Great Neck [Long Island], and I support the boycott of Israel and Israeli institutions.” A number of bloggers immediately got on the case–I can’t write or think that fast so here is Hyperallergic editor Hrag Vartanian’s report from yesterday thus in actual time on some of the details, and some artists including eco-artist Aviva Rahmani on Facebook commented on the group think and the lack of serious discussion around this announcement.

Today @ the Creative Time Summit, there was a lot of attention to a couple artists & their supporters who absented themselves in protest because they are endorsing the cultural boycott against Israel and an Israeli cultural group has been a CT partner. The boycott pre-empted, for me, attention to some wonderful artists doing wonderful work, such as Fernando Garcia-Dory, or the pleasure of visiting with old presenting friends, like Martha Rosler, Suzanne Lacy or John Malpedes. I just wrote Nato a protest letter about the lack of framing for this critical discussion and my concern that this would take over events planned for tomorrow. Personally, I profoundly deplore targeting artists because their governments have adopted unacceptable policies. If that were carried to the ultimate conclusion, no artists could ever speak to any other artists. But there is also the issue of conflating policies and peoples and how that invites, in this case, anti-semitism and ultimately, legitimizes Neo-Nazi behavior. Despite many wonderful presentations, such as Tom Finkelpearl or Laura Poitras, it was a disappointing experience of social justice practice.

According to Rahmani, in response to the protest, Creative Time “deleted the Israeli partner and took down the page of their supporters from their website. The streaming map deleted Israel.”

Afternoon keynote address speaker Tom Finkerpearl’s comments were as troubling as the cancellations, the boycott, and Creative Time’s scrubbing of Israel off the live-stream map. He said that though he admired these artists’ having the cohones (my words, not his) to cancel at the last minute, it was “bad for their career” (or did he say, “even if it was bad for their career”) and that “if you boycott Creative Time, where can you go?” I’m afraid I said out loud, “that’s ridiculous,” though I regret to say not out loud enough to be heard across the hall. Why ridiculous? Well, first because speaking both cynically but realistically, I can’t think of a better career move than to get some notoriety by taking a widely held political position favored by the elite of the hippest part of the global artworld as represented by Creative Time, without actually showing up to show your work and espouse your protest publicly with some accountability, not to mention that for the Cairo-based group, it is also not only a matter of belief but of political safety. But most ridiculous because the world of political activism that Creative Time and Nato Thompson specifically embrace is the world in which Occupy Wall Street and other groups internationally, including some represented at the event, such as artist/activist Leonidas Martin, are trying to critique the global corporate culture we all live in and are subject to. Such a critique might include a critique of the elitism that is intrinsic to any such meeting at the heart of the artworld, and one held at an educational institution, New York University (my Alma Mater, at a time when, by the way, it wasn’t that big or fancy or RICH a place) which has seen its share of criticism for its enthusiastic embrace of global capital, including its recent plans for the destruction of the very neighborhood it exists in. Are we holding a gun to political artists’ heads and saying, hey, bud, it’s Creative Time, or a one way ticket to Palookaville? That viewpoint sort of seems a bit neo-liberally arrogant.

The Creative Time Summit cost $65 including online fee for the one day I signed up for, and in a moment of cheapness brought about by the immediate effect of sticker shock at that $65, I had decided to skip the lunch offered, to be held at Judson memorial church–little realizing it was also an artwork,a sort of pedagogic political meal created by Conflict Kitchen, a take-out restaurant that only serves cuisine from countries with which the United States is in conflict–with the temporary result that as all my friends streamed into Judson Memorial Church, great refuge of the needy, I found myself standing outside temporarily nearly in tears at the economic (self-) exclusion, while painfully and belatedly aware that of course I would have to spend as much on any lunch in the neighborhood. [Personal note, lest anyone worry too much, all’s well that ends well, I did spend the same amount, but in the company of some really nice and interesting young people I ran into and was glad to talk to.]

Martha Rosler’s talk also raised, or rather did and didn’t raise, the question of the Summit’s relation to capital: she noted the irony that admission to the next incarnation of her on-going project, Garage Sale, forthcoming at MoMA, would cost up to $25 for those visitors to the museum who are not members. Since there were no audience questions at the Summit, one could only wonder why Rosler, who would have the cultural clout to do so, did not insist that admission be free to the museum during the time of her show, or, for example, since that would affect too high a percent of the museum’s admission fee income for two weeks, that anyone who participated in the Garage Sale by purchasing anything would get their admission refunded. How’s about that?

It’s not that alternatives to these situations aren’t happening all over the city and the world, small meetings in donated spaces that are happening probably every day here in New York City, where conversation follows the Occupy model or the standard panel model + audience participation–this event had no mikes set up in the aisles for audience response or questions, although a second day, today, allowed one to participate in smaller groups with some of the same participants–events where no one is paid and you fork over your dollar or so to help defray the cost of the beer. The point is, the 99%, the 47%, the struggling Occupy movement, and also the poverty of imagination of what could be the alternative to contemporary global capitalism that was addressed by Žižek, all seemed like fashionable shadows within the viewpoint of Creative Time as presented by some of its leaders and by the corporate-influenced presentational model it espoused.

Given all of these issues, having Tweets about Nato’s pants read out loud to us was one huge insult to our intelligence and situation.

In fact all this positivistic cheerleading was in significant contradistinction to the very interesting social subject matter brought into the space by many of the speakers and I would be remiss if I did not report on some of the highlights.

Going down my program in order, I was immensely impressed by the speakers who formed part of the first group, “Inequities,” including Malkia Cyril of the Center for Media Justice, a very forceful public speaker; the work of the Belgrade-based collective Škart organizing choirs composed of anyone who responded to the call for an audition even if they had never sung in their life, the project’s focus on small communities made me think of the deeply moving power of close group folk singing, as one hears on archival recordings from the American South and as I once witnessed at a fest-noz in a small town in Brittany in the early 80s. Hito Steyerl gave an elegantly resonant talk, “Is the Museum a Battlefield,” tracking her research for a work about the debris of war found in a museum back to where they were made and produced, finding herself in various corporate headquarters that all seemed to be designed by Frank Ghery, and eventually, in a circular process (literally making a circle with her hands for the feedback loop), finding that her research into the source of a General Dynamics bullet led to a corporate headquarters housing her own art work.

There were a number of feminist interventions: Jodie Evans of CODEPINK and artist and activist Suzanne Lacy brought important examples of the recent feminist history of artwork about rape and called attention to the very important Women Under Siege Project. It was great to get to see a bit more footage of Pussy Riot, presented by artist and activist A.L. Steiner, dressed only in a transparent neon orange plastic jumpsuit, her body in revelatory bright lighting, her face in shadow. On the feminist email list-serve Faces there had been a certain amount of criticism of the feminism of Pussy Riot by some Eastern European feminist artists, on the other hand there has been a lot of publicity about them without necessarily more detailed awareness of their political views and I found myself very moved by being able to see some more of what they did, by the images of them performing in the church and on the wall of a snow covered redoubt in a huge square near the Kremlin. Steiner’s presentation echoed the daring and the vulnerability of Pussy Riot, pointing to what individual women face when they try to project their bodies and voices into a huge and mostly unreceptive to downright hostile world, here embodied in the artist’s presence, strongly confrontational yet riskily exposed, and in the way her mic check style call and response of feminist statements was absorbed and dampened by the hall’s acoustic environment, highlighting its deficit in terms of the spatial and auditory intimacy required for shared political purpose.

On the other hand the raucous humor of the various projects depicted by Barcelona based artist and activist Leonidas Martin was quite wonderful and contagiously funny although one of the best pieces was video of a bank occupation, when in a kind of flash mob event, people closed their accounts at a branch of a major bank and a huge crowd of revelers suddenly materialized, eventually even making an initially stunned woman banker burst out laughing. Humor is one of the most powerful and effective political weapons, so, one wondered, why couldn’t we do that here: unfortunately when that tactic was tried last year in New York at a Citibank branch a block down from NYU’s Skirball Center, the police arrived and arrested a bunch of activists as well as possibly innocent by-standers although the Occupy activists had purposefully dressed in business attire so it was a little hard to tell, but the hilarity of the Spanish scene was preemptively aborted.

However, if I close my eyes and think of the most interesting artwork I saw, without question one work stands out, and, perhaps significantly the artist was not there, only the artwork. This was Shooting Images, (or was the title Double Shooting? I wrote both down) a video presentation by Lebanese stage and film actor, playwright, and visual artist Rabih Mroué, taking as its premise the phenomenon recently noted in Syria of citizen journalists shooting their own deaths, often on their smart phone cameras. The video is extremely simple in its means, starting with its means of address: the artist uses white on black titles with the text in relatively small type to address us, speaking in the first person. Mroué established the double shooting: the double shooters: the gun and the camera. The photographer is always “hors champs” a film term for off camera, but I believe based on a military related term for off the field of battle, like “hors combat.” Mroué first presents the scene in such a way that it appears to be real footage, the sniper and the man with the camera, whose end is nearly identical with actual documentary footage from the past few months. Then he clarifies very specifically and intimately that this is a re-enactment he created with a friend and neighbor–the insistence on this at the end of the video I think is a commentary on the tragedy of a civil war where friends and neighbors may shoot one another. The video asks if there is a way to bring the victim into the frame, in the killer’s eyes? In a fascinatingly medium specific way he magnifies the sniper’s image until, within one pixel, is the image of the cameraman/victim, upside-down in the retina of his killer. Then the bond of the reciprocal homicidal gaze bounces back and forth between the two protagonists. The discovery of the victim’s face in a single pixel detail of the killer’s eye reverses a recurring theme of murder mystery novels and movies, the idea that what the murder victim last saw would be fixed upon his retina, a reverse image of the murderer, like an internal still CCTV image capture. This was a memorable work.

The question of medium specificity is important to me partly because my own visual medium, painting, typically does not appear at such events dedicated to art of social engagement except in the guise of third world or inner city folk art, for example in the presentation by the Indonesian activist group Taring Padi and in some images that were shown by Mexican art and social activists EDELO, among many very intriguing and suggestive works including theater pieces and contingent folk sculpture. The politics of this double standard is rarely discussed.

I left at 5 because I wanted to get home to write about the exhibition of Josef Albers Paintings on Paper, an exhibition at the Morgan Library closing this weekend–in that decision were multiple ironies, that I was leaving a fashionable art event inimical to painting in order to write about an artist who in fact I had always seen as didactic in a way that could be seen as part of the repressive politics of high modernism which contributed to my move towards feminism as a young artist. It’s probably not a good political move to have your feet planted in two arenas, the powers that be that have a stake in each may not appreciate the dual vision, but to me it is a more total and enriched position.

There is political art and there are also art politics, and by politics I mean not just specific political histories and narratives but in general hierarchies and systems of power and privilege. Part of any political practice is to understand a field of action and to be able to hold in your head at least two things at the same time, that something can be very interesting, important, AMAZING even, and also occasionally problematic, with its internal power structures, which are often obscured. One always has to keep this in mind, which by the way is very different than dismissing it outright, and this is the purpose of this small intervention on my part into what was a very interesting and instructive event.

*

The presentations I’ve discussed above are now online (scroll down the site for individual presentations mentioned here) although it is important to point out that what you see online spatially and relationally to the original audience in the Skirball Center is the TV show view, with speakers seen in close up as well as occasionally in long shot, rather the audience’s theatrical experience of the speakers as small and less distinct figures on a large and, for many there, distant, stage. In lieu of a comments section here, see the contentious, interesting discussion which took place over a three day period on my original Facebook posting of this piece.

Today October 10, 2012 would be my sister Naomi Schor‘s sixty-ninth birthday.

I always like to mark her birthday in some way. This year, my birthday remembrance is about politics and newspapers. We shared a passionate, anxious, and affective relationship to politics, something we had both inherited, I believe, from our parents, whose lives had been affected by major political catastrophes and who had an interest in history and politics. One of the interests we shared was in the American electoral process. We enjoyed the theater of it, shared what we felt were the high points and agonized over the darker moments in the years we experienced them together. I know she would be completely wrapped up in the current election, as I am, and perhaps prey to the same moments of deep anxiety about the future.

Last week I went through a box of newspapers and magazines she had saved over the years and had taken the trouble to pack up and take with her for each of the several moves of her distinguished professional life. I too save copies of the paper and in some cases I suspect I have exactly the same material packed away in some box of my own. I photographed each publication in the box so that I would have some record of even those I was able to force myself to throw out, saving a few as possible research material for an approach to writing about her, part of my larger and still very germinal project of writing a cultural autobiography that, at this point, is more focused on keeping the life and work of my parents and my sister alive as long I can, not just for myself, but for what I think they can mean for anyone else.

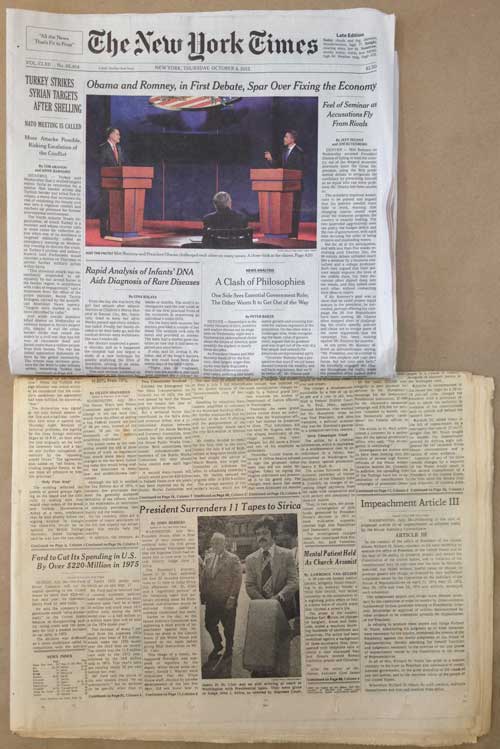

The contents of the box I went through included several example of coverage of Watergate.

The date on this newspaper is August 8, 1974, though the Wikipedia timeline states that Nixon resigned on August 9th. The resignation was announced on the 8th, and was official on the 9th when President Ford was sworn in.

Here are two other editions of the New York Times, from Wednesday, July 31, 1974 and Tuesday, August 6, 1974, as the final stages of the Watergate scandal played out across the print press and television coverage that had gripped much of the country. For myself, I had been at graduate school at CalArts in the early stages of the scandal, and I think this may have been the one point in my life I was not reading the Times regularly or particularly focused on anything except my own life: I was absorbed in new friendships, in the first class I ever taught, and was preparing my MFA show. The Senate Watergate hearings had begun May 17. When I got back to New York around the 3rd of June, 1973, Watergate was all anyone could talk about, I found that my mother and sister were obsessed with every development so I got up to speed and I watched every minute of the Senate hearings from that point on.

The first of the two copies of the Times that I had set aside, in a kind of hoarder’s purgatory, not safely back in the box for further research, not in the bunch I actually did throw out, is from two days before Nixon resigned:

The other edition I selected is from a few days before that, July 31: I was about to throw both of these copies out and just hold on to “Nixon Resigns” but when I put a current paper on top, also to be discarded, I was struck by the physical difference in size between the paper then and now:

The first thing that one notes in handling the historical copies and the paper today is that it has shrunk considerably, I believe the size has been diminished twice in the past twenty years. The 1974 paper was 23″x14½,” the current one is 22″x12″–not a huge difference but a less imposing artifact to be sure and it appears much narrower when placed next to or on top of the old version. When the newspaper last shrunk, I recall that readers were assured that the percentage of news coverage would not diminish: I remember counting the news stories in pre- and post- shrinkage editions–can’t be sure but I think that I found that, contrary to that claim, there were in fact slightly fewer news stories.

Most people would agree that this more modest scale is ecologically sound, and at this point I am just grateful I can still begin my day reading the New York Times in hard copy though diminished not just in dimensions but in amount of pages, and perhaps also in amount of news covered of a non-entertainment nature. It’s not perfect, but it is still the newspaper. One of my sister’s friends says that the one reason she doesn’t mind getting older is that she may possibly not outlive the hard copy publication of the New York Times! Nevertheless, to hold the 1974 issue is an experience with some gravitas that is perhaps lacking today. OK, already you can see the disjunction here: gravitas and news!!! I just watched The Daily Show tonight. Like a lot of people I count on Jon Stewart, a comedian, to do the job mainstream media reporters as well as sitting presidents should be doing in mano a mano combat with Republican bullshit, so that portentous experience of holding open in your hands that 46 inch full spread of 8 columns a page of news is a long long time ago.

Looking at the paper from last week’s coverage of the first Presidential debate between President Obama and Mitt Romney, the situation seems more depressing and more dire than the situation in 1974, because the peculiar thing about the Watergate scandal is that at the same time as it uncovered a plot by the President of the United States to subvert major branches of government and that it made us acquainted with some horrible people, including a close-up view of the dark soul of Richard Nixon, it also introduced us to some politicians one felt one could respect and admire, and revealed courage, integrity, and what could still seem like authentic authenticity at many levels of American culture from the press to the government. There were as many heroes as villains in the story and as I recall there was some level of continued trust in America despite everything that was revealed during the process. “The system worked,” or so people said at the time.

But things were happening in that very moment of the seeming triumph of justice and democracy that have a bearing on our own time. The stories are more linked that one might think. The 30+ year reign of increasingly right wing social politics and corporation friendly laws and Supreme Court decisions we have endured since the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980 actually began during the same period as the most vivid moments of political fervor and transformation of the 1960s, and a return to order was already being formulated during the Nixon administration. For example, the so-called “Powell Memo” or Powell Manifesto was first published in August 1971, as “Confidential Memorandum: Attack of American Free Enterprise System.” In it, then corporate lawyer Lewis F. Powell laid out most of the political goals and tactics for the right wing, calling for the creation of many of the institutions that have brought us to decisions like Citizens United and organizations like ALEC. Powell was named to the Supreme Court by Nixon two months after the publication of this document. In another example of the links between then and now, one of the few figures who did not show backbone and political heroism in the events known at the “Saturday Night Massacre,” when Nixon called for the dismissal of Watergate independent prosecutor Archibald Cox by executive order was then Solicitor General Robert Bork. Later rejected by the Senate when he was nominated to the Supreme Court by Ronald Reagan, Bork set the model for Justices like Antonin Scalia and is said to be advising the Romney campaign on Supreme Court nominations should Romney be elected.

Yesterday I spit into the wind and wrote to President Obama at “Letters to Obama:”

Dear President Obama: I hope you will fight back and fight for this election, against lies and to prevent what I think would be an incredibly dangerous President and Vice President, with Republican majority. Is this the country and the world that you want for your daughters to live in? This election is not about you indeed, it is about us, we can vote, yes, your loyal though often frustrated base will vote for you, but you are the only person on the stage who can fight back against Romney’s shape shifting lies, we can’t. So, at long last, do it..you don’t have to overact at the next debates, you just have to defend your record, your beliefs, your policies, and the truth. The country’s fate is at stake, not just your career.

Sincerely,

Mira Schor

Utterly futile and a lot more polite than what I really want to say but perhaps just a little birthday card to my sister, who would have despaired of a Romney Presidency, as do I.

*

My sister and a friend, reading the newspaper on the beach, late 60s or early 70s.

Free speech seems to be the latest thing, but in a strangely nostalgic way. This coming Saturday alone in New York City there are at least two events which will feature readings out loud from historical and contemporary political texts. Unfortunately I can’t be in two places at the same time so I won’t be able to attend “‘A riot is the language of the unheard’: an exercise in unrestrained speech” at The Rose Auditorium of Cooper Union at 4PM but wish I could. The event announcement includes this description:

Taking its cue from a quote from a 1968 speech about injustice and freedom by Dr. Martin Luther King, this public event engages in the use of the voice in imagining collective and political speech through short readings by artists, scholars, writers, poets, musicians, and speakers.

The event features a variety of contemporary and historic material such as re-performed texts, poetry, experimental theater, pedagogic exercises, as well as everyday collections of testimonials, essays, and private ruminations.

Envisioned as a “rough cut” anthology of live subversive speech acts, “A riot is the language of the unheard” is an experimental tribute to parrhesia, or defiant and confrontational speech. As surveillance and force is becoming increasingly utilized to control and manage resistance, this program seeks to address how the right to speak is also a politics of listening.

Later that day, from 6 to 8 I will be among a few artists invited to read at the closing event for an exhibition organized by some of my MFA students at Parsons, “Question for Revolution and Universal Brotherhood” where performances have included other public readings of political texts with an emphasis on utopian possibilities, some from the past but all for the current era. Invited participants at the closing events will also include Maureen Connor, Andrea Geyer, Heather Love, John T. McGrath, and Alex Segade.

Last week saw an iteration of the Free University in New York City, first initiated last May 1, with seminars taking place in the open air at Madison Square Park over a four day period, an Occupy-related event for once unmolested by the NYPD. Discussion included topics such as “What is Money – What is Debt” led by Sue Waters, “The Sirens and Subjection: Homer, Kakfa, and Adorno” led by Julie Napolin, “Letters to a Young Artist: What should young artists know?” led by Caroline Woolard (which was planning to begin with a reading and discussion on Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet), and “Discussion of The Alienated Librarian” led by Chris Alen Sula (a discussion inititated with students from Pratt Institute’s School of Information & Library Science of Marcia Nauratil’s 1989 book “The Alienated Librarian,” which examines the work of librarians from a labor perspective. (for the full schedule of events that took place September 18-22, click on the Five Day Schedule link on this Free University Page and for more photos from the event you can look at their Flickr page).

Inspired by the idea of the Free University, on Sunday October 14, I will lead a similar type of reading of Bill Readings’ predictive 1997 book The University in Ruins at Momenta Art as part of the current exhibition Occupy Your BFF, an exchange of ideas with Occupy Wall Street, with the involvement of Occupy related groups including the Arts&Labor group. Institutions including Parsons The New School of Design and the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts are hosting some of the events listed on this schedule.

This ferment, in the case of these examples mentioned above, has centered around education within and beyond the confines of the university and in many instances focused on political texts from earlier moments of political fervor, conflict, and engagement is part of a world wide growing movement of radical critique of post-War neo-liberalism and the ravages of global, unregulated super capitalism. In the US the increase in such activity seems to be framed by the crash of the 2008 economy and the upcoming election, although some within the Occupy Movement are so convinced of the evil of the two lesser of two evils argument of our electoral choices that they are rejecting participation in the vote.

While many media voices declare that Occupy is dead or has failed, discussion about the political and economic situation and how to affect it positively, continues, large or small, public events such as the ones at educational institutions or on web-based projects such as Nicholas Mirzoeff’s year long daily blog Occupy 2012 or in small ongoing private discussion groups, the large meetings inspirational and occasionally dramatic (as people on Twitter, Tumblr and Facebook share news pictures of huge mass demonstrations around the world, usually not discussed at any length if at all on American mainstream media, including such liberal sites as MSNBC, which focus on domestic events, with a tendency to get seduced by the horse-race aspect of electoral and party politics in the US). The smaller groups are interesting and moving in another more intimate way. I should note that including the Free University, I have attended only a couple of events in recent weeks, so my view is pretty limited but my sense is of a tender struggle, with a desire for positive social inclusion at the level of the everyday, for modest cumulative efforts to interject criticality but also small tangible moments of community and warmth into a media entertainment, corporatized, corrupted and alienated culture. Some of these efforts have a tentative aspect which may lead to media commentary of the death of Occupy, but these small meetings, as much as the larger public events such as the occupation of Zuccotti Park, at least reveal to each individual that they are not alone in their hopes and desires for a different and better world.

The turn to historical texts is significant in this regard. My totally unscientifc and personal view is that from the French Revolution, if you really want to go far back, through the Russian Revolution, to the crucible of the Great Depression with its powerful political battles between totalitarianism, fascism, communism and progressive liberalism, great union movements, and great battles for civil rights, women’s rights, and gay rights, up to the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980, the voices for political engagement were sharp, confident, fearless, funny, inspiring, historically rooted, with deep roots in the assertion of rebellion. The 1980s marked the beginning of the institutionalization of some of these voices into the university but underscored with a growing disappointment with the “failure” of the 60s and a creeping complicity with the corporatization of the world.

The turn to the historical texts and voices indicates a current thirst for the courage, eloquence, and, after thirty years of the triumph of irony, for the authenticity of such voices. At the same time it is quite interesting to note the trend towards re-performance, recently a hot subject of debate with regards to performance art. Events, political actions and interventions, and artworks whose contingent nature was completely a part of their meaning are now being not just celebrated but also re-performed under quite luxurious and heavily promoted circumstances–things artists and political thinkers did in conditions often of near anonymity, not that many such figures did not seek attention for their causes and themselves and document their practices as best they could, but I still would describe as near anonymity relative to current conditions of instant self-documentation, promotion, and commodification on pretty much everyone’s part. One problem is that questions of political belief and authenticity are still hard to bring up, in fact I type these words with censorious critical voices loudly whispering in my ear!

The interest in something like a Free University is also an indication, a recognition that things are not quite so rosy in institutions of higher education, just as they are not rosy in the public school system, in fact in every system. The moral economy of the 1% occurs in every part of culture: we see some of the public protests against the marketization of education, in faculty and student protests against closing of liberal arts departments, libraries, and archives and in the firing of even University Presidents, or, rather, some of these situations are so egregious that they actually get some coverage, but also we see the kinds of small repressions and erosions of knowledge bases that take place throughout the university system in favor of new global imperatives connected to the very same system critiqued by the Occupy movement. Some things will no longer be taught, and thus eventually some may then reappear in the small instances of extra-institutional education Free University proposes and is just one example of, or indicator of the need for–all the more significant as higher education becomes too expensive for even upper middle class people and begins to seem non-cost effective as jobs do not exist for the subjects being taught, particularly in the liberal arts and arts.

This is what has led me to be interested in extra-institutional teaching situations though perhaps it may be therefore inferred that even some such erosions and repressions take place right in the middle of the most progressive institutions in the name of the most advanced political positioning.

In this blog I have occasionally linked to some of the stirring political speeches and the closeness to historical turmoil that marked the generations before me. These framed my initiation into politics in my early teens: the admiration (the word is not sufficient) my parents’ generation had for Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt and the policies of the New Deal–which current Right Wing politics in the US are intent on finally at long last repealing, after 80 years of concerted efforts to do so. My parents’ experiences with fascism and the Holocaust and the formative experiences of their American friends in the Great Depression and during the post-war McCarthy era were a strong influence on me as I grew up listening to their stories. In recent years as labor unions have come under attack, I have often thought about the general tendency towards progressive political thinking within immigrant groups in the US that had experienced political and religious repression in the lands of their birth and how these tendencies were part of what drove the labor union movement in the US in the early twentieth century. The political figures who I witnessed through the 60s and 70s had been formed in these crucibles and carried their traces still even as post-war economic conditions began to shift towards the situation we are currently struggling against. These are just some of the experiences that marked the atmosphere of the pre-1980s period as I experienced them, as were the examples of civil rights leaders and workers such as Fannie Lou Hamer and Martin Luther King Jr.

My interest in the possibilities of the structure of Free University seminars is based on experiences I have related on this blog before, in a provocatively titled and, significantly, pre-Occupy post, including one comment that alas will ring in my mind for years, a student’s negative comment in a faculty evaluation of me to the effect that “she made us listen to a speech by Martin Luther King” in a seminar on contemporary art issues (King’s “Beyond Vietnam” speech delivered April 4, 1967, a year exactly before his assassination). Apparently the market based expectations of students (how will this help me be a viable contemporary artist and promote my work?) clashed with my feeling that certain kinds of speech are more important than the orthodoxies of critical theory or some art discourse as well as art market gossip that still hold sway even as such types of speech are now being celebrated in the events that I mentioned at the beginning of this post happening this week in educational and alternative art institutions this week in New York City.

Politics is not for the faint of heart and can be mind-spinningly complex and soul-breakingly frustrating, as are most human beings, and because of that an engagement with politics can end up making people flee back to the interests of their daily lives. As in the past it is the realization that the safety and comfort of those personal lives are contingent and subject to larger historical forces that turns our attention again to political speech from other times when such threats were also great and yet a political perspective was more part of common thought.

*

Despair and possibility for political activism through speech are also concerns of my current visual work:

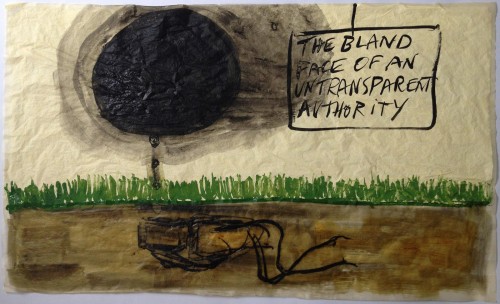

Mira Schor, The Bland Face of An Untransparent Authority, ink and gesso on tracing paper, 2012 — a pessimistic realist view

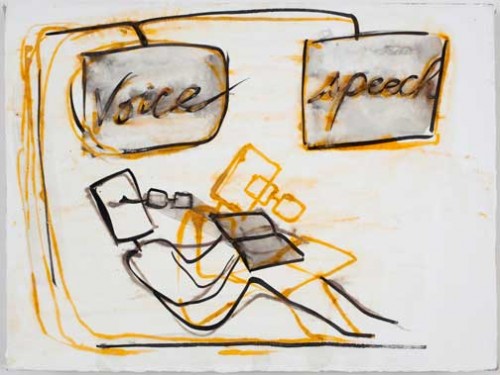

Mira Schor, Voice and Speech, 2010. Ink and rabbit skin glue on gesso on linen, 2010. The optimistic activist view

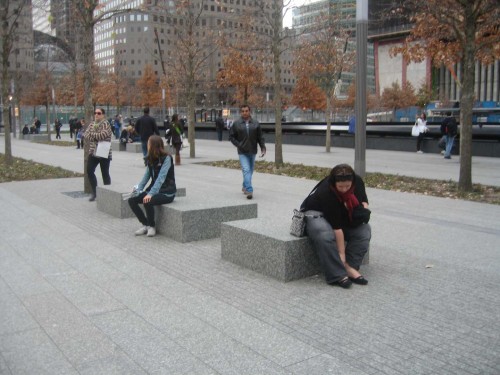

For the past ten years on September 11, I’ve republished a text I wrote in the weeks after that day, to bring the texture of the event as witnessed by so many New Yorkers with their own eyes and of daily life in Lower Manhattan in the days and weeks afterwards. But this year I don’t feel like it. My need to continue the memory has been interrupted by the National September 11 Memorial which I visited November 15, 2011, for which friends and I had reserved tickets two months in advance and which turned out to be on the same day that a police raid had evicted Occupy Wall Street from Zuccotti Park.

That day I wrote down my impressions, perhaps today’s eleventh anniversary is the day to publish them.

My initial notes as written in bold face on the spot went as follows: 9/11, 45 min wait, airport security, bad vibes, hideous entrance, bad plaza (Starbucks, Metropark architecture & lamps), terrible compromise but the two pools are dark, black abyss, death, a cold corporate architecture really works, it looks both small and huge, like a simulacral sea, it’s the opposite of the Towers of Light, what goes up via light into dark here cascades down into dark.

Getting to the entrance of the memorial is an ordeal, today (November 15, 2011) an ordeal twice over. First the issue was how walk past Zuccotti Park without having time to stop to photograph the police occupying the Park. Then, corner Thames and Albany Streets, the interminable and graceless line to get into the Memorial.

This is not a promising beginning to the memorial experience. You shouldn’t have to make an appointment to visit a memorial. Even if admission is free, grief must be free to roam and it must be integrated into daily life, here the grid of Lower Manhattan, to be both special and a silent partner, there if you want it, when you want it. Last fall, a two-month wait for a daylight hour visitor’s pass was followed by a 45 minute wait in a line effectively several blocks long though snaked through police barricades on the South side of the WTC construction site (to the accompaniment of construction noise that would certainly drown out any noise from OWS). We went through three checkpoints with our visitor’s pass, only to find ourselves at the end of the line in a chaotic mini-airport security situation, with metal detectors, put your coat and bag in a plastic bin (you don’t have to take off your shoes, thank goodness given how chaotic the situation was, I figured the logic of that was that if you blew yourself up you wouldn’t take anyone else with you though the logistics were such that people would be trampled in the line slowed down). Then down another bleak work barricaded back area, and finally into the Memorial Park…you hardly know once you have entered because there is no entrance as such. So far, bad vibes and not because of memories of why you have come, in fact the wait is so unpleasant that by the time you’ve been on line for an hour or so, you forget the reason you came.

The plaza won’t help you remember. It’s really spectacularly mediocre, New Jersey Transit/ Metropark train station parking lot atmosphere including the lamps, at the moment rather silly looking trees that somehow never transcend the function of little architectural model fake trees.

The plaza has no sense of scale. Perhaps if and when the area is no longer a work site and if in that case there is free access from the streets around, there will be a flow into the life of the city, that might make it better, but as my friends pointed out, the plaza at the World Trade Center was always a cold windswept bad space. Still, we imagined various alternatives: the last vestige of facade, the bronze orb, damaged yet intact, or just the gravel of a Japanese rock garden would be better. Best would be a flat plain space with no adornment, just gravel or marble, the trees are silly, a false niceness.

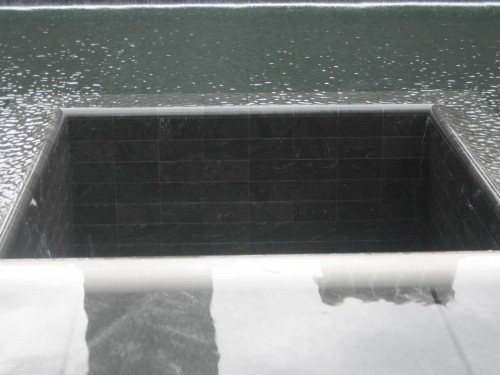

The pools are the thing itself, death, loss, the abyss, the unknown.

You approach the first pool set into the footprint of the North Tower. It is both small and huge, it seems as large as an inland sea, though a strangely simulacral one, like in a sci-fi movie, yet too small to have been the footprint of such a tall building, and though ocean-like, probably the water is only one foot deep.

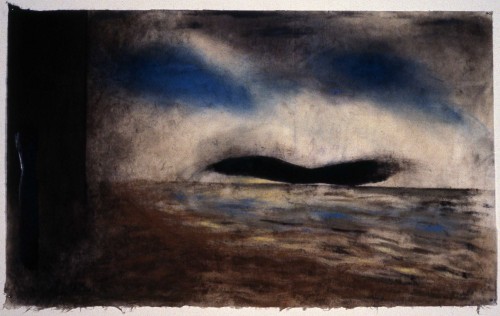

Inner Sea, a work on paper I did in 1981, from a dream of a vast sea within the interior of an urban structure

A shower of water cascades down the four dark stone walls of the giant square into the darker seemingly bottomless abyss of the inner square at the bottom of the pool.The water passes through a kind of comb that subtly recalls the e style arches of the WTC facade, though here the pattern goes downwards.

The design of the pools is brutal, corporate, and it really works.

Morning of September 11, 2012

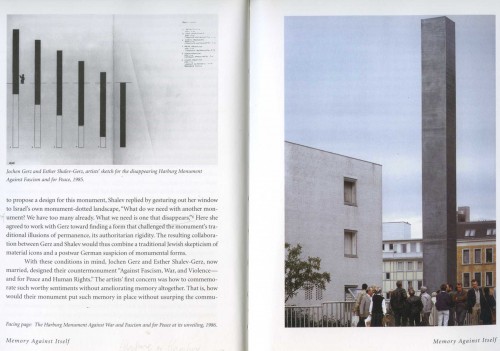

As the reading of the names proceeds in the background, a kind of musical chairs game of loss–on whose name will the reader stop to reveal their particular relation of grief?– I get out James E. Young’s At Memory’s Edge: After Images of the Holocaust in Contemporary Art and Architecture, and look again as some of the examples of “counter-memorials” in Germany in the 1990s, including from among the submissions to a 1995 competition for a German National “memorial to murdered Jews of Europe.,” in the chapter “Memory, Countermemory, and the End of the Monument: Horst Hoheisel, Micha Ullman Rachel Whiteread, and Renata Stih and Frieder Schnock.”

Artist Horst Hoheisel … proposed a simple, if provocative antisolution to the memorial competition: blow up the Brandenburg Tor, grind its stone into dust, sprinkle the remains over its former site, and cover the entire memorial area with granite plates. How better to remember a destroyed people than by a destroyed monument?…Hoheisel’s proposed destruction of the Brandenburg Gate participates int eh competition for a national Holocaust memorial, even as its radicalism precludes the possibility of its execution. At least part of its polemic, therefore, is directed against actually building any winning design, against ever finishing the monument at all. Here he seems to suggest that the surest engagement with Holocaust memory in Germany may actually life in its perpetual irresolution, that only an unfinished memorial process can guarantee the life of memory.

Some more general remarks by Young have bearing on the type of memorial that has become the default style in the United States, first expressed in Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial which so brilliantly melded modernist abstraction with literary content-the names etched on the marble surface. Lin’s piece has a quality of the antimemorial, as it is set into the earth and is quite un-obstrusive in the landscape, really it is an inscription into the earth (see picture on Wikipedia site as observed from above) until you are right up along it where only at its center does it reach above the visitor’s head. A visit to it is a surprise, because it just kind of appears as you walk towards it and its meaning can only be understood through walking by with your body and observing other people interacting with it. It’s intimate. What the designers of the 9/11 have borrowed from Lin is the most successful, thus architect Michael Arad‘s design for the pools and his use of inscribed names. The landscaping is clearly a huge concession to the demands of urban planners, politicians, victims’ families, and real estate forces who would not have understood a less utilitarian and conventional approach.

Like other cultural and aesthetic forms in Europe and North America, the monument–in both idea and practice–has undergone a radical transformation over the course of the twentieth century. As intersections between public art and political memory, the monument has necessarily reflected the aesthetic and political revolutions, as well as the wider crises of representation, following all of the century’s major upheavals–including both World Wars I and II, the Vietnam War, the rise and fall of communist regimes in the former Soviet Union and its Eastern Europeans satellites. In every case, the monument reflects both its sociohistorical and its aesthetic context: artists working in eras of cubism, expressionism, socialist realism, earthworks, minimalism, or conceptual art remain answerable to the needs of both art and official history. The result has been a metamorphosis of the monument from the heroic, self-aggrandizing figurative icons of the late nineteenth century celebrating national ideals and triumphs to the antiheroic, often ironic, and self-effacing conceptual installations that mark the national ambivalence and uncertainty of late twentieth-century postmodernism.

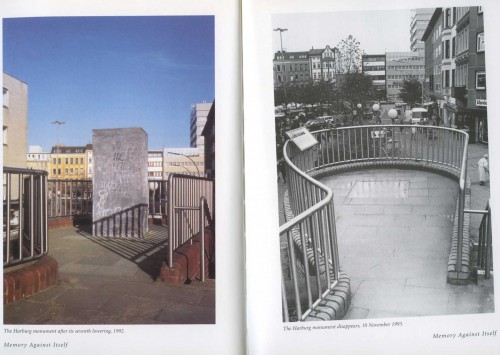

A number of the monuments described in the book seem to have a relevance to the 9/11 Memorial. Artist Jochen Gerz and Esther Shalev-Gerz‘s The Hamburg Monument Against War and Facism and for Peace, from 1986, was a “forty-foot high, three foot-square pillar ..made of hollow aluminum plated with a thin layer of soft dark lead. Visitors were invited to inscribe their own names on the monument with a steel pointed stylus and as soon as a five foot section was filled with names it sank “into a chamber as deep as the column was high.” Over seven years the monument disappeared. “The best monument, in the Gerzes’ view, may be no monument at all, but only the memory of an absent monument.”

An unrealized project submitted to the 1995 competition by Renata Stih and Frieder Schnock also stays in my mind: Bus Stop–The Non Monument proposed “an open-air bus terminal for coaches departing to and returning from regularly scheduled visits to several dozen concentration camps and other sites of destruction throughout Europe.” The artists called for “a single place whence visitors can board a bright red bus at a regularly scheduled time for a nonstop trip both to such well-known sites as Auschwitz, Treblinka, and Dachau and to the lesser known massacre sites in the east, such as Vitebsk and Trawniki.” Finally, “at night the rows of parked and waiting buses, with their destinations illuminated, would become a kind of “light sculpture” that dissolves at the break of day into a moving mass to reflect what Bernd Nicolai has called “the busy banality of horror.”

You know that the designers of the 9/11 Memorial were well versed in the history of these memorials and countermemorials.

November 15, 2011

Speaking of unwelcoming windswept spaces, on my way home I circled Zuccotti Park, now occupied by the NYPD, with Occupy Wall Street, ordinary New Yorkers, and the press occupying the periphery. In a weird topsy turvy opposites world, the police now occupied the park, and the occupiers surrounded them.

*

The problems of the 9/11 memorial and the political atmosphere that led to the Occupy movement are linked, as the reaction of the United States to the attacks of September 11 in some way was a disturbing mirror image of the forces that attacked on September 11 (a mirroring described in the 2004 BBC Documentary The Power of Nightmares, which posits parallels between the rise of the American Neo-Conservative movement and the radical Islamist movement, making comparisons on their origins and noting strong similarities between the two. In a way the destruction of the United States continued via its own internal processes of paranoia and ulterior political motives unrelated to the actual event–let’s just start its wasting of resources on a war on the “wrong” country…many others have developed these ideas better than I can do.

*

The truest antimemorials to 9/11 were perhaps the modest, temporary ones that sprang up on the site in the months after September 11, and the simple constructions on the site that were built for early anniversary observances.

Site of the World Trade Center, cardboard circle, September 11, 2002, New York City

And the most outstanding memorial remains The Towers of Light, or The Tribute in Lights. It seemed last year that we were seeing the last of them as authorities were grumbling about electricity costs. But tonight as in the past several years I’m going downtown to get as close to them as I can.

I don’t plan to go back to the Memorial until it is, if ever, integrated into the flow of the city, and I can walk there as my feet and spirit take me. That would be what–one little fragment of–democracy looks like.