I wrote this appreciation of Stephan von Huene, the American sculptor later based in Germany, upon the publication of a beautiful catalogue of “Tune the World,” his retrospective exhibition at the Hamburg Kunsthalle, 2002-2003. Living in New York City I could have only the diminished pleasure of reading the catalogue, Stephan von Huene, Resounding Sculptures, rather than the full pleasure of experiencing works whose synaesthetic performances remain fresh and vivid in my memory. However the catalogue with its accompanying CD does a great service in bringing to mind a wonderful and complex artist, human being, and for me, a teacher and mentor of inestimable importance.

Perhaps some of my reflections on his role as my teacher at a particular historical moment may be of some value in deepening the contextualization of his work while giving some personal impressions of the man. He was my mentor at CalArts after I left the Feminist Art Program. There are some people in one’s life who are absolutely irreplaceable, Steph was one of them. He remained a supportive friend and benevolent influence for me until his untimely death from cancer September 5, 2000. At that time, I had hoped to find a publisher for a draft of this text but was not able to do so. Here it is part of a group of posts exploring the theme of “Teaching Contradiction.” In this case the “contradiction” is that Stephan was the most nurturing teacher I had in graduate school and thus as much a Feminist teacher as any other.

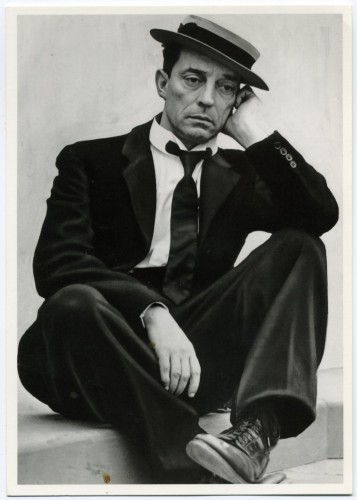

I met Stephan von Huene when I came to study painting as an MFA student at CalArts in 1971.If one can set the artistic or more precisely the art academic scene of that moment, the dominant aesthetic philosophy of American art schools and art departments of universities was that of Greenbergian formalism. Painting had to be large, abstract, oil or acrylic on canvas. Period. No figuration, no narrative, no overt personal or political content. Sculpture was not particularly considered, but perhaps it is enough to say that it was often taught in dark and greasy garage-like environments by large, heavily bearded men wielding heavy power tools and acetylene torches (in Canada they called them “tuskers”). Of course, in the wider art world there were movements that contradicted these aesthetic imperatives: pop art provided an enjoyable outlet for younger artists interested in popular culture, there were the Hairy Who artists such as Ed Paschke, based in Chicago, who were practitioners of a kind of cartoon-like, colorful surrealism. Beyond that were the possibilities for time-based performance art and for non-art suggested by Nam June Paik, Charlotte Moorman, by John Cage, Fluxus and other underground art movements. But typically these had not penetrated the art academy.

Finally, any desires that might be specific to a feminist investigation of art and culture were only on the verge of being named. Just as CalArts welcomed the Fluxus movement in the person of Alison Knowles, Emmett Williams, and also artists such as Allan Kaprow and John Baldessari, so it was the first school in North America, indeed anywhere as far as I know, to welcome the new movement of feminism as part of its educational program. This was one of the reasons I chose the school.

The CalArts Feminist Art Program, run by Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro, was an exciting and intense experimental aesthetic and political educational program embedded within this already experimental art school. The women who chose to work within it were provided a unique political education and were given the opportunity to be artistic pioneers, as art subject matter, materials, history and theory were reevaluated and re-written. However, because this was a radical experiment that included a critique of gendered systems of power, the atmosphere in the program could become quite charged, as the professors dealt with questions of authority within a political movement dedicated to the critique of authority.

Given the situation I have just described, it may seem strange that I chose Stephan von Huene as my official “mentor” for my second year of study. The retrospective of his works provides a focus for an understanding of why in fact he was such an appropriate “feminist teacher.”

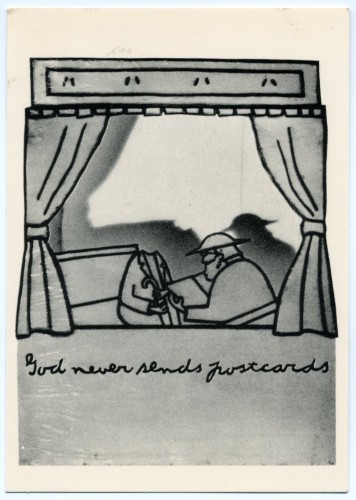

His contribution to my development was first and foremost to treat me with the greatest courtesy as a person and to appreciate the specificity of my work: at the time, I painted small gouaches representing personal narratives in a style related to artists whose work I only came to hear of through the research activities of the feminist program, such as Florine Stettheimer and Frida Kahlo. From a Greenbergian point of view these were “illustrative,” a pejorative description. If the goal of teaching through nurturing rather than through abuse was a primary rhetoric of the feminist art program, I found Stephan to be the most nurturing of the teachers I encountered at CalArts. He respected the criteria by which I wished the work to be judged. Since my principal interest at the time was to tell the story of my development as a young sexual being and at the same time to challenge the limitations set by the dominant formalist aesthetic, a formalist critique of the work seemed irrelevant, although even at CalArts it was the prevailing method, at least when it came to painting. So here was Stephan embracing the delicate role of art therapist at the same time as he prodded me into accepting change, chance and accident as formal and methodological principles, always with gentleness and humor.

He also shared his own searches and discoveries, from his work and life, his readings, and even from the psychotherapy he told me he had been in or perhaps was undergoing at that time. Again this was an unusual teaching method, revealing what might be interpreted as weakness while retaining the authority of knowledge and wisdom.

The few times he intervened in a more traditional, formalist, or simply practical manner were few but therefore memorable: for example, he once told me that he could tell the size of a person’s studio just from looking at the work – this seemed like a magic trick, but it is one that has served me well as a teacher. When the ceiling of my studio was damaged by a major leak, damaging delicate gouache on paper paintings I had lain on the floor, he said with his characteristic humorous exuberance, “This is great, you should put all your work in the shower!”

The most important studio visit came a year after I had graduated. Stephan visited my studio in New York. He made it clear that he was not pleased with the work I’d done since I left school. He felt that I’d lost my direction, what he had felt was special to my work. I don’t remember exactly what he said, though I can still see him in the room. In fact what happened is that I instantly translated his sparely voiced critique into an interpretation of what I should do next to get back to the core he seemed as committed to as I was (or, rather, in that moment, to which he was more committed than I seemed to him to be). The resolve formed in that moment of translation and erasure of the actual comments set me back on the path that I have followed since. I could only even half hear his criticism because he had been supportive of my work and my criteria of judgement.

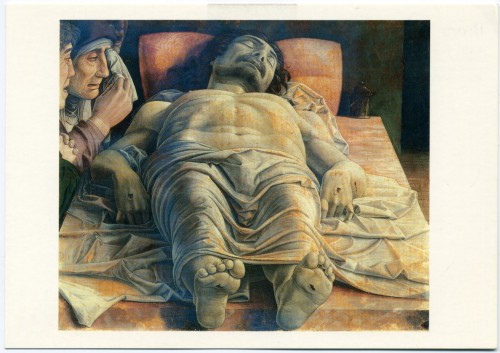

Most astonishingly, in relation to my being a painter, he once told me that he hated “pigmentation.” This is so revealing when one thinks of works he did in the mid-70s such as the Glass Pipes, where he seemed to desire a total dematerialization of art — “the sculptural direction toward nothing,” he writes. I felt that this work represented a life and death struggle for freedom from embodiment, and yet took the form of the sound of a scream, one of the most elementally embodied, reflexive human reactions of shock, fear, and existential horror. As a painter, I found his disgust with pigmentation funny but also bracing and it never interfered with his attitude as a teacher.

Stephan did not believe in showing students his own artworks. Or rather, he believed one shouldn’t try to influence students into imitation of the teacher’s work by immediately impressing the students with his style. Could there be any better example of his unwillingness to abuse professorial power than to deny himself that aspect of stylistic influence that appeals to so many who teach? And perhaps something else was at play, a kind of privacy, diffidence, and maybe the sense that his work was unusual and inimitable.

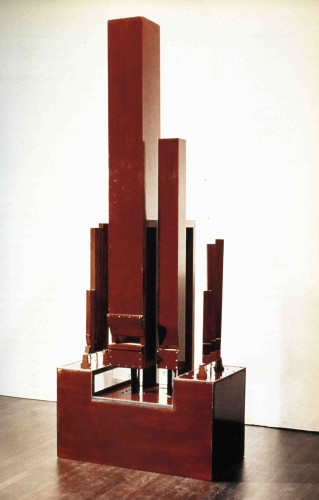

Stephan von Huene, Totem Tone III, 1969-70, wood and mixed media with sound

But finally I did get to see a few of his works, at the end of my first year at school. My memory is a little shaky but I know that I saw one of the Totem Tones at CalArts (see reference & sound link near the end of this post) – a strange, beautiful, uncompromising object emanating weird, funny but also forbidding sounds, yet welcoming through the warmth of the beautifully crafted wooden materials. Beauty and strangeness, science with archaic mechanisms emitting modern atonal sounds, the work seemed perfectly matched to the person, whose aristocratic demeanor commanded a particular respect – and it amazes me now to realize that he was then only 39 years old.

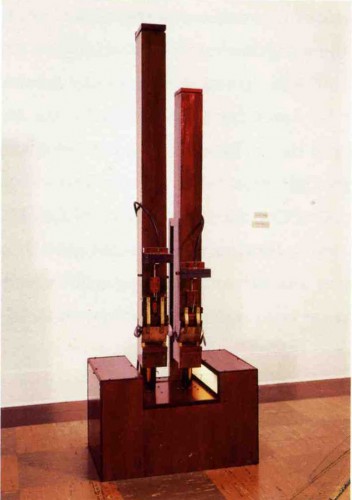

Stephan von Huene, Rosebud Annunciator, 1967-69, wood, leather, computer and mixed media

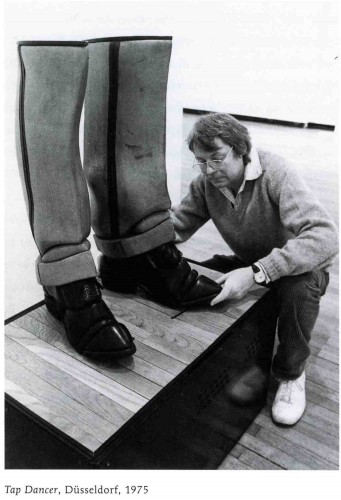

Around the same time, I believe that I also saw Tap Dancer and Rosebud Annunciator at his home.

Stephan von Huene, Tap Dancer

These works then and now also suggest why he was such a perfect teacher, though a man, for a feminist female young artist in the context of the then prevalent LA “fetish finish” art movement. The relation to Surrealism perceptible in his work was resonant for many women artists including myself interested in narrativity and representation of sexuality. The work’s use of dark wood and his variant of fine crafting seemed to have more to do with the California Arts and Crafts movement of the early twentieth century than with the prevalent surfer culture. William Wilson does a good job in his catalogue essay of describing the art world of Los Angeles in the late 60s and the anomalous position of von Huene within that context. His work had some connections with that of Ed Keinholz, as has been noted. But socially he didn’t play the macho game; in fact stories from that scene would cause him to flinch as if recoiling in pain and distaste. He was marked by his early childhood experience of cultural otherness, as the child of German immigrants, and that gave him a sensitivity to similar experiences in others.

In his work, his developing interest in technology somehow had a different feel to it than that evidenced in contemporary work dealing with technology. He didn’t aspire toward the glorification of plastic. There was an increasing formal reductivism to his work in the 1970s, but he exercised an older type of craftsmanship, in much the way that Walter Benjamin noted that new technologies, when first realized in utilitarian objects, retained archaic traces, so that, for example, the first automobiles retained the outward form of the fanciest, hand-crafted horse-driven carriages, before the full impact of mass production streamlined form to function. The early works had a strange quality of surplus and quaintness of materials in order to create rather primitive sounds. And in later works such as The Semiconductor of Chemnitz there are again traces of the archaic: the face of the figure echoes the faces of mannequins in Atget photographs, just as its mechanisms seem caught somewhere between an 18th century automaton and a robot created at MIT.

Many of his works used metonymic representation of gendered body fragments in ways that reflected surrealist roots. Surrealism had been the demonized other of modernism, in the terms of the New York school: this is a recurrent theme as one can see in the writings of Clement Greenberg and Barnett Newman, among others. As feminist art sought visual form for the depiction of female sexual desire, the surrealist movement provided important models. The surrealist movement has continued to exercise an important influence on feminist art and theory because, although the surrealist artists themselves may have been unregenerate in their views about femininity: placing irrationality and madness in the feminine, at least they prized those states of being. Thus their work and that of the theorists surrounding their group, such as Bataille and Lacan, opened the door for later feminist investigation.

Von Huene’s works shared some of the characteristics of a reflection of gender identity as something learned, as a system of signs: as in many later works such as Tischtänzer, gender identity is telegraphed through a reduction of the body to a headless dancing pair of pants or tights, a system of culturally marked codes. The feminist art historian Carol Duncan had written an influential analysis of much representation of the female nude in vanguard modernist painting, “Virility and Domination in Early Twentieth-Century Vanguard Painting,” focusing on the violence done to the subjectivity of the female models, often most blatantly signaled by formal, compositional decapitation. Von Huene returned in many works to the bottom half, the sexed half, but of both men and women, and always with a focus on the signs of gender such as clothing or scale. Also appropriate to a feminist interpretation is the frequent awkwardness of the fragmented body part: the legs and boots of Tap Dancer teeter between a military appearance and the suggestion of a medical condition, transposition of right and left feet, or two left feet perhaps. Certainly his depictions or intimations of women are never exploitative, never deliberately sexually disturbing in the manner of an artist like Hans Bellmer for example.

Fragmentation, figuration, gender, craft, lack, these were all areas of interest that had strong connections to the interests of much feminist art investigation at the time and feminist psychoanalytic theory of later years.

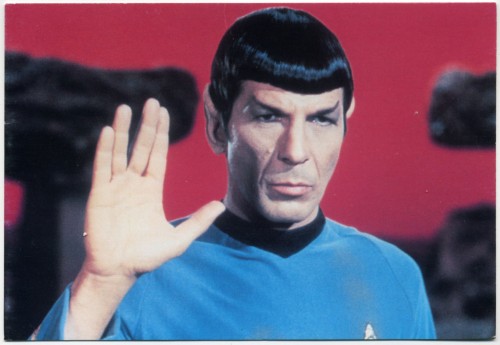

Finally von Huene’s unusual relationship to dominant or dominating systems of power are important components for What’s Wrong with Art and Blaue Büche in which he uses formal elegance to contain his distaste for abuses of power in the art world. From percussion as pure declarative sound, in Drum, for example, he moves in Blaue Büche and Der Mann von Jüterborg to speech as a percussive instrument of power. In Drum the mechanical devices that drive the drumsticks prefigure the robots that run the world in The Matrix, while in Der Mann von Jüterborg the slow pace of an invisible man moves like a marionette, following in a disturbing yet powerful slow motion the drum beat of human speech. These works develop a sophisticated critique of systems in which the spirit of creativity and of phenomenological investigation is frustrated and perverted by market values. In these works he continues to be a valuable teacher as well as a unique artist.

Stephan Von Huene and his piece Text Tone, 1083

Stephan von Huene was born in Los Angeles in 1932 of German-born parents. He studied at the University of California in Los Angeles (UCLA), and then received his BFA from Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles in 1959. He received a Master of Arts degree from UCLA in 1965.

In the 1960s, Von Huene exhibited wood and leather sculptures at the Pasadena Art Museum. His early work was noted for its Pop and surrealist sensibility and for his highly refined craft. He taught at Chouinard Art Institute in LA, and California State University, LA. Between 1971 to 1976 he was a teacher and Dean at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), along with Alan Kaprow and Paul Brach. He also taught at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in 1974 and received a National Endowment for the Arts grant that year. In 1975 he completed Drum, a commission with James Tenney, for the Exploratorium Museum in San Franscisco.

In 1976-77 Von Huene received a DADD grant to work in Berlin. He later moved to Germany where he was based in Hamburg and taught at the Art Academy in Karlsruhe (Staatliche Hochschule für Gestaltung Karlsruhe), as well as at the Fachhochschule fur Gestaltung, Hamburg, Germany. His work was included in Documenta 8.

Von Huene’s acoustic sculptural work Text Tones is one of the major works in the contemporary collection of the Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Berlin’s Museum for Contemporary Art.

Totem Tone V, (1969-1970), a von Huene sound sculpture is in the collection of the Hirschhorn Museum in Washington, D.C. and was discussed by artist Evan Holloway in a podcast accompanying the 2006-2007 exhibition The Uncertainty of Objects and Ideas: Recent Sculpture, curated by Anne Ellegood. You can hear it play toward the end of the podcast, about 29 minutes in.

Stephan von Huene, Totem Tone V, 1969-70

Selected Bibliography

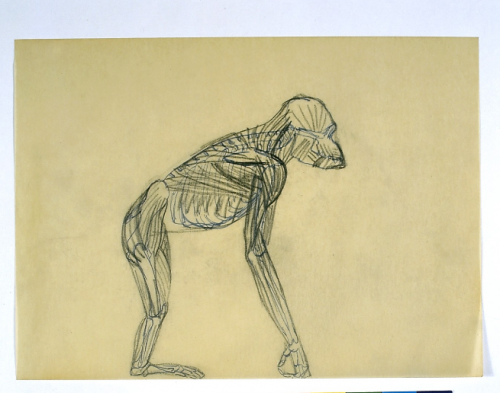

Stephan von Huene, The Song of the Line, The Drawing 1950-1999, by Marvin Altner, Petra Oelschlager, Petra Kipphoff, Stephan von Huene, Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2010

Stephan von Huene 1962-2000: Catalogue Raisonée, by H. Bredekamp, Petra Kipphoff, J. La Barbara, F. Michel, Petra Oelschlagel, Martin Warnke, Christoph Brockaus, Olaf Breuning, Stephan von Huene, Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2003.

Stephan von Huene: Klangkorper/Resounding Sculptures, by Stephan von Huene, Martin Wanke, and Christoph Brockhaus. Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2003

For more information:

Stephan von Huene Wikipedia article (German)

Stephan von Huene, official website

“Tune the World: Sound Sculptures, Pictures, Drawings,” at the Haus der Kunst, Munich, review